Some of Rome’s Worst Rulers nobody talks about

Rome’s worst emperors were not defined by excess alone. From rigidity and paralysis to paranoia and absence, these reigns reveal how imperial power failed – and why those failures mattered.

The Roman Empire is often remembered through its greatest rulers: emperors who expanded borders, stabilized institutions, or left monuments that still define the ancient world. Yet imperial power did not always produce capable leadership. At moments of crisis, ambition, fear, and misjudgment rose to the highest office, shaping reigns remembered less for achievement than for their consequences. This is not a catalogue of sensational excess, but an examination of how emperors could fail – and what those failures meant for Rome itself.

A System Designed to Prevent One-Man Rule

The Roman Republic was designed to prevent the concentration of power. Authority was deliberately divided: the consulship was shared, limited to a single year, and supported by a senatorial system intended to restrain individual ambition. For centuries, this framework functioned effectively, even as Rome expanded. Its failure emerged in the first century BCE, when long-term military commands allowed successful generals to build personal armies whose loyalty lay with commanders rather than the Senate.

This shift produced a new political reality. Figures such as Marius, Sulla, Pompey, and Julius Caesar exploited military power to override republican norms, culminating in Caesar’s dictatorship and assassination. His death did not restore the Republic but deepened instability, as violence and factionalism replaced constitutional authority. Power increasingly followed force rather than office.

Into this environment stepped Octavius, later Augustus. Like his predecessors, he relied on armies and civil war to secure dominance, but he differed in presentation. In 27 BCE, he formally returned extraordinary powers to the Senate, only to receive new authorities that allowed him to govern without openly claiming supremacy.

The Republic survived in name, while its substance was transformed. By styling himself princeps and combining tribunician power, provincial command, and imperium, Augustus ruled without appearing to rule.

Stability was maintained through calculated satisfaction. The people received grain, money, and games; the army was rewarded with pay, land, and campaigns; the provinces gained more consistent administration. Alongside these measures, Augustus carefully projected virtus, presenting himself as restrained, moral, and traditional while reshaping the political system. He also controlled his legacy through monuments, laws, and narrative, ensuring favourable remembrance.

This Augustan balance established the standards by which emperors were judged. Rome’s worst emperors were not defined solely by cruelty or eccentricity, but by failure to sustain this equilibrium – alienating the army, humiliating the Senate, neglecting governance, or subordinating stability to personal indulgence. The evaluation that follows examines imperial failure on these Roman terms, focusing on why such reigns damaged the system Augustus had constructed.

Galba: The Emperor Who Should Have Ruled – But Didn’t

Before becoming emperor, Servius Sulpicius Galba embodied traditional Roman ideals. His lineage was ancient and distinguished, his public service extensive, and his career marked by military competence and strict administration. Ancient sources consistently portray him as a man of virtus: disciplined, morally upright, and committed to ancestral custom. Tacitus captures the paradox that defines his legacy, observing that Galba appeared fully suited to rule – so long as he remained a private citizen.

His governorships in Africa and Germania reinforced this reputation. Order was restored through rigorous discipline and scrupulous justice, qualities that earned him honours and priesthoods. Even earlier opportunities for imperial power were declined, suggesting restraint and political judgement. On paper, Galba represented exactly the kind of figure Rome believed it needed after Nero.

A Temperament Ill-Suited to Empire

The qualities that defined Galba’s earlier success became liabilities once he reached the throne. His governing style was inflexible, punitive, and rooted in outdated Republican severity. Stern discipline had proven effective in provincial command; applied in Rome, it appeared cruel, archaic, and politically tone-deaf.

From the moment he entered the city, Galba demonstrated a refusal – or inability – to adapt to the expectations of emperorship. Public mercy (clementia) and generosity (liberalitas), now essential tools of imperial legitimacy, were largely absent. Executions were carried out on suspicion alone, citizenship was rarely granted, and privileges were dispensed sparingly. In a capital accustomed to Nero’s largesse and spectacle, Galba’s austerity was interpreted not as virtue but hostility.

Galba’s arrival in Rome was marked by bloodshed. When sailors petitioned him for recognition as a legion – an appeal created by Nero’s own policies – Galba dismissed them. When they protested, he responded with overwhelming violence, ordering cavalry charges into a mixed crowd of civilians and petitioners. Survivors were subjected to decimation, a punishment already viewed as archaic and extreme by first-century standards.

This episode set the tone for his reign. Discipline was enforced publicly and brutally, without regard for optics or public morale. Rather than signalling renewal after Nero, Galba’s actions evoked fear and resentment. His physical frailty and age further contrasted with the energetic, performative style Romans had come to associate with imperial leadership.

His most consequential failure lay in his relationship with the military. He owed his elevation not to the Senate, but to the Praetorian Guard’s abandonment of Nero. That reality shaped expectations. The Guard had been promised generous donatives and expected reward for making an emperor.

Galba refused. Declaring that he “levied soldiers, not bought them,” he denied payments not only to the Praetorians in Rome but offended soldiers across the provinces. This stance may have reflected Republican virtue, but it ignored the transformed political reality of imperial power, which now rested fundamentally on military loyalty.

The consequences were immediate. The Praetorian Guard became hostile and embittered. Provincial armies took note. If one legion could make Galba emperor, others could do the same.

The Collapse of Authority

While Galba alienated Rome, power shifted elsewhere. In Germania, seven legions proclaimed Vitellius emperor. In the capital, Marcus Salvius Otho secured the support of the Praetorian Guard by promising what Galba had refused. On 15 January 69 CE, Galba was murdered in a coup that was swift, violent, and largely unresisted.

His death did not restore order. Instead, it triggered the Year of the Four Emperors, a sequence of civil wars that devastated Rome and its provinces. Tacitus, reflecting on that year, described it as one:

“rich in disasters… horrible even in peace.”

Why Galba Was One of Rome’s Worst Emperors

Galba’s failure was not moral corruption, cruelty for pleasure, or personal excess. It was political incompetence at a structural level. He ruled as though the Republic still existed, ignoring the realities Augustus had established. By alienating the people, humiliating petitioners, and – most disastrously – misjudging the army, he dismantled the fragile consensus that sustained imperial rule.

Galba stands as a cautionary figure: a man perfectly suited to rule before the empire existed, but disastrously unsuited to rule within it. His seven-month reign destabilised the state and opened the path to civil war. That systemic failure, rather than personal vice, secures his place among Rome’s worst emperors.

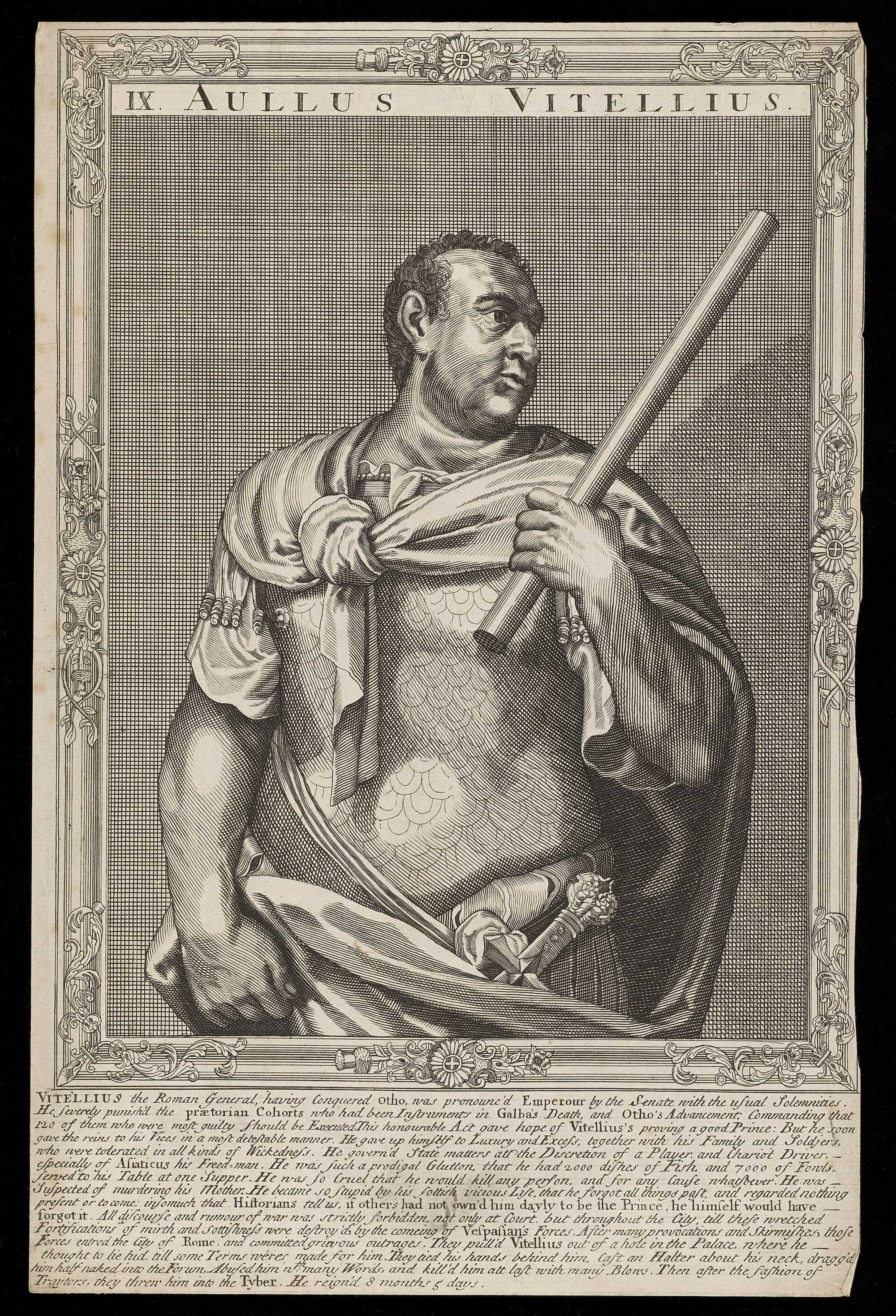

Vitellius (69 CE): No Appetite for Power

Vitellius became emperor not through ambition or ability, but because the Rhine legions decided he would do. A career courtier rather than a commander, he had survived under Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero by flattering imperial tastes and attaching himself to their pleasures. Ancient sources concede that he could show competence in office, but they present his elevation as accidental—a product of military discontent and the manoeuvring of generals who needed a respectable name to front their cause.

Once proclaimed emperor, Vitellius appeared to treat power as licence rather than responsibility. Tacitus and Suetonius both dwell on his indulgence: constant banquets, extravagant feasts, and the exhaustion of towns forced to feed his entourage as he moved toward Rome. This emphasis on gluttony is not incidental.

In Roman moral thinking, excess signalled softness, and softness marked a man unfit to rule. Vitellius’ reign was thus framed as the inversion of virtus: pleasure replaced discipline, consumption replaced action.

More damaging still was his failure to control the army that had made him. The Rhine legions flooded Rome, brawling in the streets, ignoring discipline, and indulging in violence that even Tacitus struggles to describe. Their decay – through idleness, disease, and lack of leadership – coincided with the rise of a rival emperor, Vespasian. Faced with this threat, Vitellius did nothing decisive. He suppressed discussion, punished messengers, and retreated into denial rather than preparing defence or rallying support.

When his position collapsed, Vitellius attempted to abdicate in exchange for his life and a vast sum of money. For Roman authors, this act sealed his reputation. Emperorship was imagined as public duty; to abandon it for personal gain was the ultimate failure. He could not even manage a peaceful withdrawal, and Rome descended into street fighting. Captured by Vespasian’s troops, Vitellius was dragged through the city and killed, mocked by the same crowd that had once hailed him.

Vitellius is remembered as a worst emperor not simply for excess or cruelty, but for emptiness. He neither sought power nor understood it, failed to command the army, refused to act in crisis, and ultimately chose survival and money over responsibility. In a year defined by civil war, his reign exemplified how disastrously the empire could suffer when authority fell into the hands of a man with no appetite for rule.

Domitian (81–96 CE) – The Last of the Flavians

Domitian’s political instincts were shaped early by trauma. During the civil wars, he was trapped in Rome while his father and brother gathered forces in the East. He was placed under guard, then swept into the violent collapse of Flavian resistance on the Capitoline. The burning of the Temple of Jupiter and the brutal execution of his uncle, Flavius Sabinus, unfolded at close range.

Domitian escaped only through disguise and concealment. His later devotion to Jupiter as protector reflected a lifetime awareness of how abruptly power could vanish.

Living in a Brother’s Shadow

Throughout Vespasian’s reign, Domitian was publicly visible but unmistakably secondary. Dynastic imagery paired him with his father and Titus, yet advancement flowed primarily to the elder brother. Titus accumulated military glory and public affection; Domitian accumulated frustration. Attempts to secure independent military distinction were blocked, reinforcing a sense of exclusion from the honours that defined Roman legitimacy.

When Domitian became emperor, he proved capable and energetic. He administered justice carefully, pursued corruption, regulated finances, restored major buildings, expanded Rome’s infrastructure, and invested heavily in public spectacle and religious observance. He was attentive to detail, particularly in ritual and administration, and expected praise for precision as much as for grandeur. In policy and practice, much of his rule followed Augustan precedent.

Where Domitian diverged sharply from earlier emperors was in his relationship with the Senate. He showed little interest in preserving the fiction of shared governance. Power was concentrated openly in the emperor, senior offices were filled without deference to senatorial entitlement, and the court increasingly followed Domitian rather than remaining anchored in the Senate House. The political centre moved with him, often to his residence outside Rome, reducing the Senate to a body summoned rather than consulted.

Domitian’s reign became defined less by mass executions than by intimidation. Prominent men were put to death on charges that appeared selective and unpredictable. Surveillance, informers, and calculated displays of menace fostered a climate in which silence felt safer than loyalty. Senators and courtiers alike learned that status, past service, and even family connection offered no protection. Authority was enforced not only through law, but through anxiety.

The Turn After Revolt

A failed revolt in 89 CE hardened Domitian’s rule. Suspicion deepened, punishments intensified, and personal security became obsession. Old remarks, minor incidents, and distant associations were treated as evidence of threat. Measures once justified as vigilance slipped into paranoia. Even members of the imperial household began to fear that proximity to the emperor was itself dangerous.

Domitian was not overthrown by senators, but killed by his own household. Senior palace officials coordinated the assassination, convinced that no loyalty could guarantee survival. The emperor fought fiercely, but the violence of his death reflected the complete collapse of trust at the heart of his court. His removal was followed by immediate condemnation and the erasure of his memory.

Why Domitian Belongs Among the Worst

Domitian failed not through incompetence, but through alienation. He governed effectively, built extensively, and enforced order, yet ruled in a way that made fear central to power. By abandoning restraint, humiliating the elite, and allowing suspicion to dominate decision-making, he created the very conspiracies he sought to prevent. His reign demonstrates how an emperor could administer Rome successfully and still destroy the conditions that made imperial rule sustainable.

Nerva (96–98 CE) – The Stopgap Emperor

Nerva became emperor immediately after the assassination of Domitian. His elevation was driven by urgency rather than ambition. Rome had lived through the chaos of an empty throne before, and memories of 69 CE remained vivid. A rapid settlement was essential to prevent unrest in the provinces or intervention by the armies. Nerva, elderly and politically unthreatening, offered an immediate solution.

He lacked the qualities traditionally associated with imperial authority. He had never commanded troops, governed a province, or distinguished himself in war. His public record consisted of a praetorship and two consulships, one shared with Domitian. What set him apart was not achievement, but the absence of a following. He inspired no faction, commanded no loyalty, and posed no threat to rivals.

Despite his limited career, Nerva had been favoured by previous emperors. He was conspicuously rewarded by Nero after the exposure of the Piso conspiracy and elevated early under Vespasian. The services that earned these rewards remain unclear, but they suggest discretion, loyalty, and usefulness within the imperial system. These same qualities made him acceptable to both the Senate and surviving Flavian supporters.

A Senatorial Restoration

Once in power, Nerva reversed the coercive practices of Domitian’s final years. Treason trials were abandoned, exiles recalled, confiscated property returned, and informers silenced. He pledged not to execute senators and upheld that promise. Government proceeded in consultation with the Senate, restoring dignity and influence to a class that had ruled in fear.

Nerva governed according to traditional ideals of moderation and legality. He funded land distributions for the poor by selling imperial property, enacted reforms presented as just, and emphasised personal restraint. These actions earned senatorial approval and public goodwill, but they did not secure obedience.

Failure with the Army

The legions and the Praetorian Guard remained hostile. Domitian’s assassins were left unpunished and continued to operate within the palace. Financial rewards failed to compensate for Nerva’s lack of military standing. To soldiers accustomed to emperors who campaigned alongside them, Nerva appeared weak and expendable.

In 97 CE the Praetorian Guard openly defied the emperor. They surrounded the palace, seized Domitian’s killers, and executed them despite Nerva’s resistance. The emperor’s authority was ignored, and the inviolability of his person was effectively broken. The humiliation exposed the limits of senatorial power in the face of armed force.

Why Nerva Belongs Among the Worst

Nerva failed not through cruelty or excess, but through incapacity. He could not command the army, restrain the Guard, or protect the authority of the imperial office. His reign demonstrated that senatorial approval alone was no longer sufficient to rule Rome. Emperors now required military legitimacy. Nerva’s role was transitional, and his most consequential act was selecting a successor capable of ruling where he could not.

Lucius Aurelius Verus (161–169 CE) – Overshadowed

Lucius Aurelius Verus ruled Rome as emperor for eight years, yet he is frequently absent from lists of Roman emperors. Even modern summaries of the Antonine dynasty sometimes omit him altogether. This habitual neglect is striking, given that his reign was legitimate and contemporaneous, and doubly ironic considering his apparent determination to be noticed – whether by accentuating his blond hair with gold dust or cultivating one of antiquity’s most memorable beards.

He is often treated as if he barely existed. In historical memory, Lucius Verus disappears behind his co-emperor as though his name were an editorial inconvenience rather than a constitutional fact.

A Talent for Leisure

The neglect is undeserved in one respect: Lucius Verus left behind a trail of vivid anecdotes. Most concern his leisure activities, which were neither subtle nor restrained. Like other aristocratic youths before him, he reportedly took pleasure in visiting taverns in disguise, an activity that sometimes ended badly. On one such occasion he returned home with his face bruised and swollen after being beaten by those he had chosen to provoke.

He also enjoyed more destructive amusements. Large coins were thrown into cookshops for the pleasure of smashing cups and crockery. Chariot racing, gladiatorial contests, and gambling occupied much of his attention, as did hosting extravagant banquets. One feast was said to have cost six million sesterces, largely because of the extraordinary gifts bestowed on the guests.

These presents went far beyond polite tokens. Guests received crystal goblets, jewel-studded gold cups, gold perfume containers, silver serving ware, and live animals matching the dishes served at the table. The household staff were also distributed as gifts, with each guest receiving a servant. To ensure the smooth transport of this haul, Verus provided carriages, mules, muleteers, and silver trappings so his guests could return home properly equipped.

Portraits of Lucius Verus depict an emperor with an imposing beard, a dense mass of curls that contemporary writers likened to barbarian fashion. The beard was worn long and carefully tended, and ancient descriptions suggest that Verus took particular pride in his appearance. His fondness for luxury extended even to his drinking vessels.

Among his prized possessions was an enormous crystal goblet, named after a horse he favoured, so large that it exceeded the capacity of an ordinary human draught.

Taken together, these details form a consistent picture. The biographical tradition portrays Lucius Verus as a man who enjoyed pleasure, display, and generosity, someone who delighted in fine things and knew how to entertain on a grand scale.

Scandal Without Conviction

Attempts to attach darker stories to Verus are notably half-hearted. Rumours circulated of an illicit relationship with his mother-in-law Faustina and even of poisoning involving oysters, but the sources themselves express scepticism. These allegations are presented as gossip rather than conviction, and are explicitly described as inconsistent with his character.

Unlike other emperors, Verus resists easy transformation into a villain. The biographical tradition struggles to find credible moral outrage, and the lack of enthusiasm with which scandal is reported speaks volumes.

Lucius Verus died in 169 CE, possibly from illness contracted during the eastern campaigns, though the precise cause remains uncertain. Marcus Aurelius lived on for another eleven years, long enough to secure his reputation through endurance, reflection, and authorship. His private philosophical writings ensured his lasting presence in cultural memory, while Verus faded into obscurity.

As a result, Marcus Aurelius became synonymous with the period. His image, words, and name persist, while Lucius Verus is reduced to a footnote, if he appears at all.

An Emperor Without Impact

Lucius Verus does not fit comfortably into a catalogue of Rome’s worst emperors. His reign was not marked by cruelty, incompetence, or disaster. Contemporary judgement is blunt: he neither overflowed with vice nor distinguished himself by virtue. His failure lay elsewhere.

He left little imprint on the office he held. The work of ruling was carried out by his co-emperor, and posterity followed suit. In the end, Lucius Verus is remembered less for what he did than for how easily he was forgotten. For an emperor, that absence of impact was itself a form of failure. ("Ancient Rome's worst emperors" by L.J.Trafford)

Imperial failure in Rome rarely followed a single pattern. Some emperors collapsed under the weight of power they could not control; others ruled competently yet fostered fear, resentment, or instability that outlived them. A few failed simply by leaving no mark at all. What unites these reigns is not scandal, cruelty, or excess alone, but the inability to sustain the fragile equilibrium Augustus had constructed. When that balance broke – between army, Senate, people, and emperor – the consequences were never confined to the ruler. They were borne by the empire itself.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: