Septimius Severus: Founder, Fighter, and Father of a New Rome

From the sands of Africa to the edge of Britain, Septimius Severus rose as an emperor forged by ambition and war. Neither Rome-born nor Senate-chosen, he remade the Empire in his image—provincial, militarized, and enduring.

When Septimius Severus marched into Rome in 193 CE, he did so not as the Senate’s choice, but as the army’s—toppling Didius Julianus, the short-lived emperor installed after a praetorian coup.

Born in the African city of Leptis Magna, he was no heir to Roman aristocracy, yet he would remake the Empire in his image—disciplining its institutions, elevating its soldiers, and securing his sons as his successors.

His reign, forged in the fires of civil war, marked the beginning of a new political reality: one in which military power, provincial roots, and dynastic ambition would override the old Republican ideals. Severus was not merely an emperor—he was a founder, a fighter, and the architect of a harsher, more resilient Rome.

A New Emperor from Africa

Once the Roman imperial system had settled into permanence, it seemed to matter little who wore the purple.

“As for the Emperor and the Emperor’s friends, and fortune’s dance… certain names shooting up like flames to a great height of glory and being extinguished—there is complete silence on these things here, our ears are spared from news of that sort...”

Synesius, Letter to a friend

His jest, drawn from life in distant Cyrenaica under Arcadius in the early 5th century, came with a rebuke: in his treatise On Kingship, he urged that the emperor must be present—touring the provinces, leading the army.

Septimius Severus, although not recorded visiting Cyrenaica itself, came close to fulfilling this vision. He was the first emperor to be both born and raised outside Rome and Italy, growing up in the heart of Tripolitania.

His path to power—beginning with his senatorial career—took him across the empire: from Sardinia to Spain, Syria, Gaul, Sicily, and Pannonia, with a formative interlude in Athens.

After seizing power, he spent only four of his eighteen years as emperor in Rome. The rest unfolded in constant movement—campaigning in the east where he pushed Rome’s frontier to the Tigris, visiting Egypt, the Balkans, the Rhineland, his native Africa, and ultimately, remote Britain, where he remained longer than any emperor before him.

His African roots were no less remarkable. Recent scholarship has underscored the distinctiveness of Tripolitania, which remained conservative and culturally self-contained long after becoming part of the Roman world under Augustus. Its Punic or Libyphoenician identity remained strong, undisturbed by waves of Roman settlement.

The old elite, however, responded promptly to Roman authority. Lepcis, already a free city, had secured allied status early, and Septimius’ family was among the first to rise within the new order.

His grandfather had become a Roman knight, held land near Rome, and was known in the literary world of late Flavian Italy, before returning to Lepcis to preside over its transformation into an honorary colonia. His father remained rooted in Tripolitania; Septimius himself spent his youth there.

Severus’ African background shaped more than just his biography its influence extended to the imperial household’s diversity, seen in his Syrian-born wife Julia Domna and the broader Severan dynasty’s eastern character.

In a world of many languages—Latin, Greek, and others—Severus emerges as a figure deeply shaped by his provincial origins, one whose rise reflects the layered, often misunderstood dynamics of a changing Roman world.

From Lepcis Magna to Rome

Septimius Severus was born on April 11, 145 CE, in the prominent city of Lepcis Magna, located in the province of Tripolitania. He was the son of Publius Septimius Geta and Fulvia Pia.

At the time of his birth, Lepcis had held the rank of Roman colony for a generation and was one of the most distinguished cities of Roman Africa. The name Tripolitania—“land of three cities”—referred to Lepcis and its neighbors Oea (modern Tripoli) and Sabratha.

The empire itself was then at the height of prosperity, under the rule of Antoninus Pius. The emperor, consul for the fourth time in 145 alongside his adopted son Marcus Aurelius, gave the period its association with peace and affluence.

The infant was named Lucius Septimius Severus, after his paternal grandfather. Half a century later, as emperor, he would retroactively adopt the Antonine dynasty to bolster his legitimacy—declaring himself “son of the deified Marcus” in place of “son of Publius,” a calculated move to link his reign to the respected legacy of Marcus Aurelius.

This retrospective adoption did not pass without comment: one senator dryly remarked that Severus had “found a father,” an insinuation that his true origins were unremarkable. While Geta never held public office and died long before his son’s rise in 195, he was not without standing.

Two members of his family—likely his cousins—were already senators in 145 and held promising careers. Geta himself remained in Tripolitania with his wife and their three children: another son, probably the elder, who shared his name, and a daughter named Octavilla.

Though the details of his life remain obscure, the Historia Augusta claims that Marius Maximus discussed him “quite copiously” in his biography of Severus, even if it offers no surviving account of that discussion.

Lepcis Magna, where Severus spent the first seventeen years of his life, was no ordinary Roman city. Among the patchwork of communities across the empire, Lepcis and the other Tripolitanian cities stood out for their distinctiveness.

To understand Septimius Severus' background, it is essential to explore the early history of his native city, Lepcis Magna. Founded as a Phoenician trading post by settlers from Tyre and Sidon, Lepcis developed within a wider Punic network that dominated the western Mediterranean until Rome’s rise.

While Carthage was the leading power, Lepcis retained a distinctive Libyan identity, reflected in its name and location along important trans-Saharan trade routes.

Stage (proscaenium and frons scaenae) and orchestra, from the Roman theatre in Lepcis Magna. Credits: Sebastià Giralt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The region’s fertility, particularly the Cinyps valley, was noted by Herodotus, and though Greek colonists made occasional attempts to settle nearby, they were eventually pushed out by local and Carthaginian forces.

With Carthage’s decline after the Punic Wars, Lepcis gradually shifted into the Roman sphere. By the second century BCE, it maintained a degree of independence and later aligned with Rome during the Jugurthine War, becoming a treaty state (civitas foederata).

Despite its political integration, Lepcis preserved its Punic religious and civic institutions well into the late Republic. Local coinage and inscriptions show continued devotion to deities like Melqart and Shadrapa, while Punic remained in use, though written in a cursive script. The city avoided major disruptions during Rome’s internal conflicts and remained prosperous, especially through olive oil production.

It was discovered that in 1961–2 the military site at Carpow on the Tay in Scotland was of Severan date—its stone principia and praetorium confirming that the emperor had intended to conquer the entire island, just as Cassius Dio had claimed. Later visits to Lepcis Magna, crossing the desert from the Garamantian region past Bu Ngem—the Severan frontier fort—offered further context to that ambition.

During Caesar’s civil war, Lepcis was penalized for supporting his opponents, yet it remained a significant urban center. Under Augustus, Africa’s provincial structure was consolidated, and Lepcis was gradually incorporated into the Roman provincial system—marking a transition from its Punic past to its imperial future. (Septimius Severus: The African Emperor, by Anthony R. Birley)

Septimius Severus and Roman Africa

Septimius Severus was the only Roman emperor originating from the province of Africa, and scholarly assessments of his reign and policies have varied significantly. Recent discoveries, particularly an inscription from Lepcis, encourage a fresh examination of Severus' family background, ascent to imperial power, and connections to Roman Africa.

Severus’ ancestry has sparked debate, notably around a lyrical ode by Statius dedicated to a friend named Septimius Severus. This Severus, admired for oratory skills, had settled in Italy, prompting debate about his relation to the future emperor.

Evidence strongly suggests he was not the emperor's direct ancestor but belonged to another branch of the same equestrian family from Lepcis, with family members reaching senatorial ranks in Rome during the second century. Inscriptions, including those at Lepcis and Praeneste, confirm Severus’ familial connections and further indicate Italian origins, specifically marked by the tribe Pupinia, rare outside Italy.

Severus’ maternal family, the Fulvii, likewise had Italian roots, engaged prominently in the imperial cult, suggesting Severus’ ancestors were not indigenous Africans but Italian immigrants. Severus benefited significantly from family patronage, notably through his relatives C. Septimius Severus and P. Septimius Aper, who occupied influential positions.

His own political career, however, showed no remarkable distinction before his imperial proclamation. Severus held relatively minor posts, experienced significant periods without appointments, and notably lacked military distinction despite later characterizations as a military emperor. His assignment to Pannonia Superior by the praetorian prefect Laetus seems motivated more by Severus' perceived mediocrity and lack of military ambition than any regional solidarity among Africans.

Claims about Severus’ alleged Punic racial identity and cultural sympathies are largely unsupported. Anecdotes alleging Severus’ sister spoke little Latin or that Severus himself favored Punic language lack credibility, appearing as rhetorical slander rather than factual evidence.

Though from Lepcis, Severus and his family embraced Roman and Greek cultures, distancing themselves from Punic traditions.

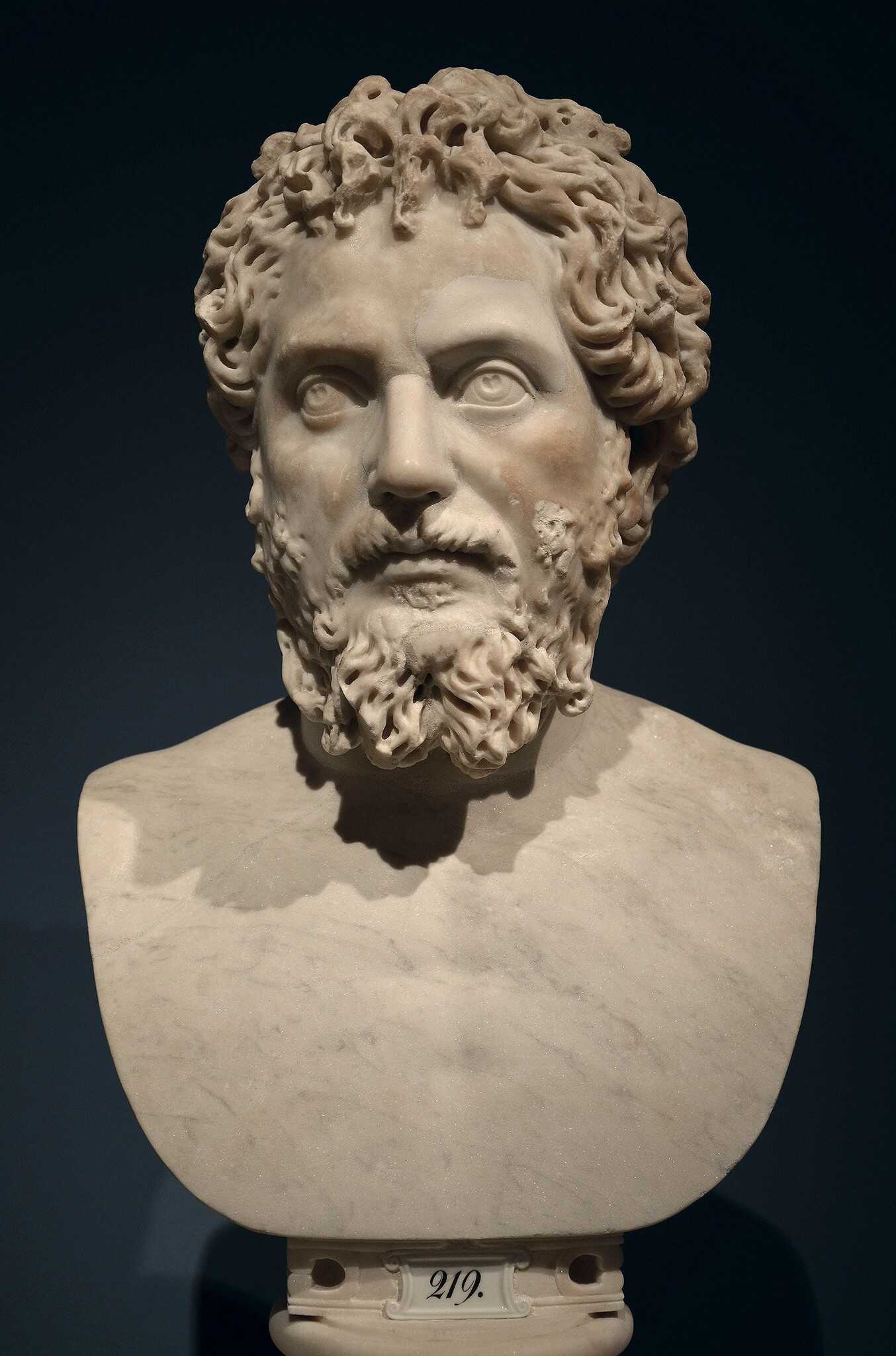

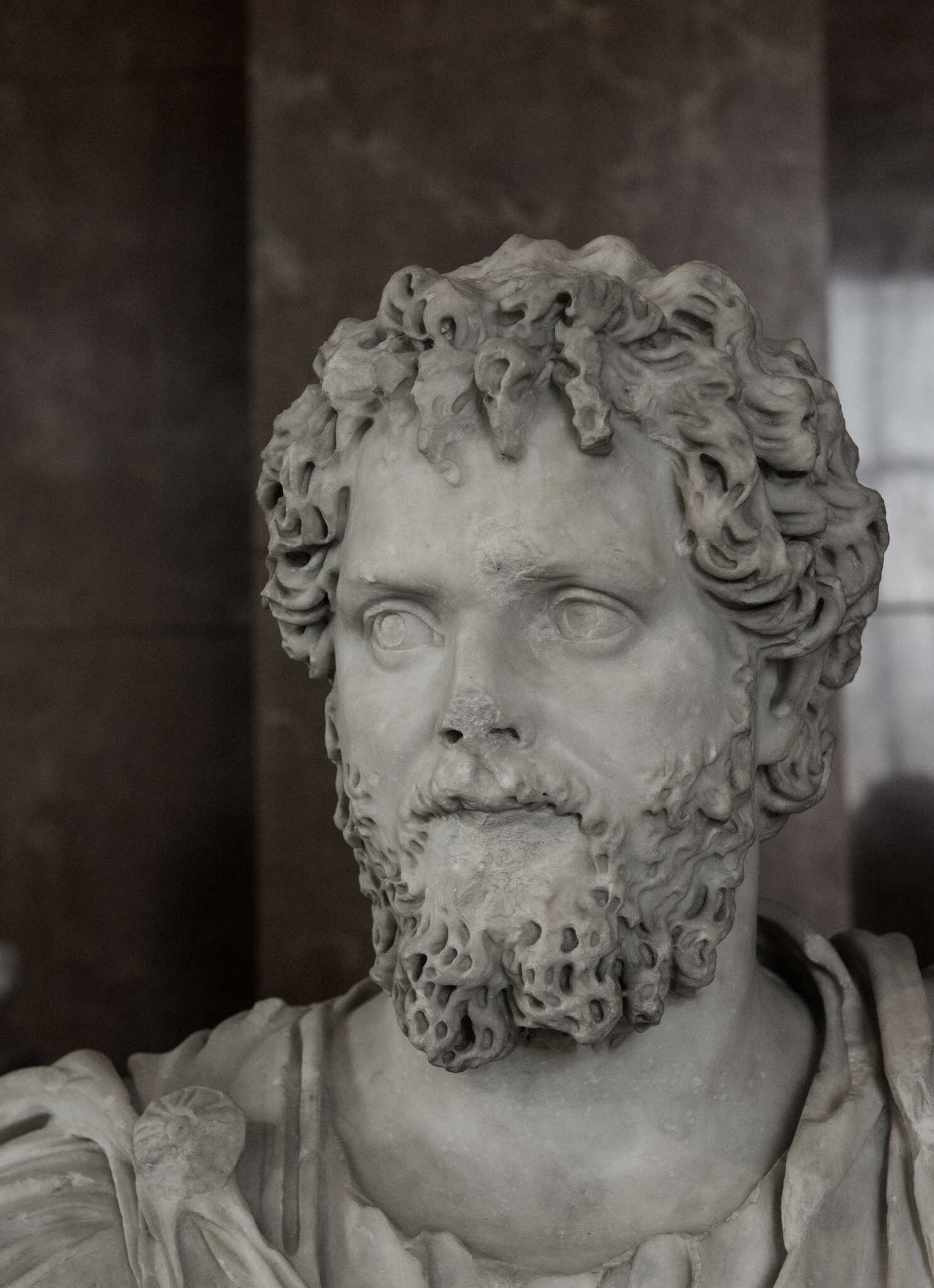

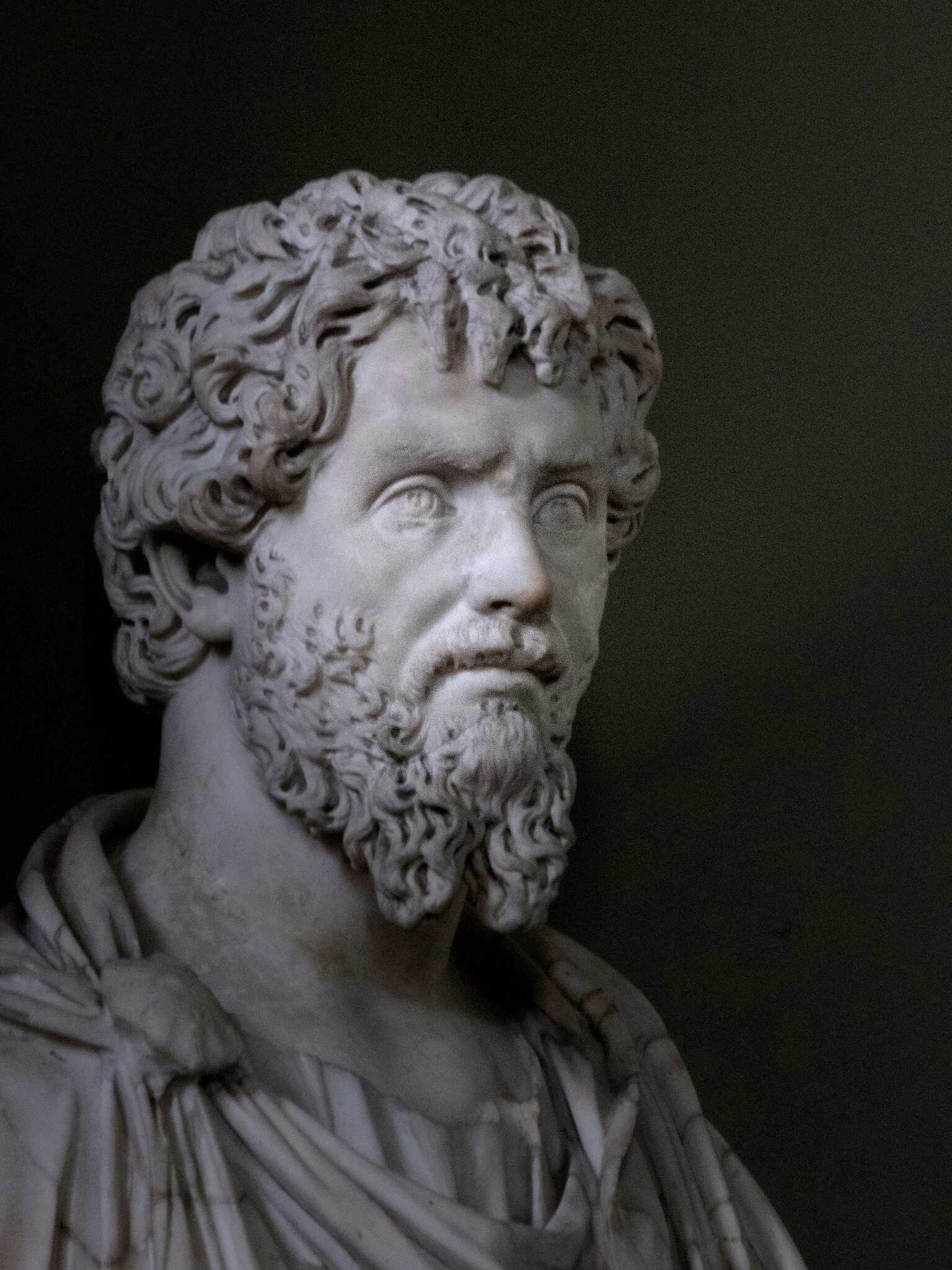

A bust of Roman Emperor Septimius Severus. Credits: Marc Barrot, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Severus' policy as emperor did not reflect a bias toward African interests. Contrary to suggestions of favoritism, his administration continued established Roman practices of provincial promotion and integration into the senatorial and equestrian classes without particular preference for Africans.

African cities, including Severus' birthplace Lepcis, received benefits and privileges; however, these were consistent with broader imperial policies toward prosperous provincial cities rather than signs of specific regional favoritism.

Even Severus' famed architectural patronage in Lepcis largely served to glorify his hometown rather than Africa broadly.

Detail of the portico of the Roman theatre in Lepcis Magna. Credits: Sebastià Giralt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In military and administrative appointments, Severus favored competent and ambitious individuals from across the empire, underscoring opportunism and ambition as key motivators among his supporters, rather than regional or ethnic allegiances. Notably, African governors and generals, such as Plautianus and Laetus, rose through merit or opportunity rather than inherent regional solidarity.

Overall, Severus’ African heritage was not significantly reflected in his imperial policies or actions beyond a personal and sentimental attachment to Lepcis. Scholarly attempts to emphasize his African identity and its impact on his governance overestimate the significance of his origins, overlooking the broader imperial contexts, political circumstances, and practical considerations shaping his rule. (The Family and Career of Septimius Severus, by T. D. Barnes)

Septimius Severus in Herodian

Septimius Severus occupies a central role in Herodian’s History of the Empire, uniquely portrayed as a decisive, energetic, and shrewd emperor, whose character shapes the coherence of a turbulent period. Unlike Cassius Dio’s broader historical narrative, Herodian emphasizes Severus’ personal traits and deliberate contrasts with rivals Didius Julianus and Pescennius Niger, casting Severus as a figure of vigorous action against their passivity and indecision.

Herodian repeatedly structures his portrayal through careful parallels and contrasts. Severus' strategic manipulation and rhetorical mastery emerge clearly against Niger’s hesitant optimism and Julianus’ weak inaction.

Severus’ swift march on Rome, careful alliance-building, and rhetorical promises further highlight these differences, demonstrating his effectiveness as both military leader and political tactician. Upon arriving in Rome, Severus reinforces his earlier rhetoric by decisively punishing Pertinax’s murderers, demonstrating consistency between his words and actions.

Herodian highlights Severus’ calculated use of deception against the Praetorians and carefully frames his entry into Rome through internal reactions—fear from the populace, cautious support from the Senate—rather than visual spectacle, as Dio does. Severus skillfully aligns himself rhetorically with virtuous predecessors such as Pertinax and Marcus Aurelius, even as Herodian selectively omits unfavorable details found in Dio, thus maintaining Severus’ positive image.

His narrative of Severus’ later years emphasizes his continued dedication to imperial administration and moral instruction of his sons. His careful handling of Plautianus’ conspiracy emphasizes threats posed by overly ambitious praetorian prefects, positioning Severus as a cautious reformer who splits prefectural power while upholding administrative responsibilities, unlike Commodus.

Severus’ thoughtful education of his sons, particularly through his advice about fraternal harmony, recalls Marcus Aurelius’ virtuous model. In depicting Severus’ final campaign in Britain, Herodian further underscores Severus’ military excellence, omitting hardships detailed by Dio, thus reinforcing the emperor’s established traits of determination and effectiveness.

The final scenes highlight Severus’ parental challenges, showing Caracalla’s destructive tendencies contrasted with Severus’ continued efforts toward familial harmony. He concludes by carefully paralleling Severus’ death with Marcus Aurelius’, emphasizing their shared dedication to imperial duty despite illness and family tensions.

Soldiers' enduring loyalty to Severus' memory briefly maintains harmony between his sons, demonstrating his lasting influence. Through sustained rhetorical parallels, carefully structured contrasts, and selective narrative omissions, Herodian presents Severus as an exemplar of imperial strength, capable administration, and complex legacy within Rome’s chaotic era. (Herodian's Septimus Severus: Literary Portrait and Historiography, by Chrysanthos S. Chrysanthou)

In life, Septimius Severus marched farther than any emperor before him; in death, he left behind a Rome reshaped—not by birthright, but by will, war, and the reach of a man from Africa.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: