How did Romans Go to the Toilet and Use Urine in Ways we Cannot Imagine Today

How did the Romans go about… number one and number two, and how did they utilize their human waste?

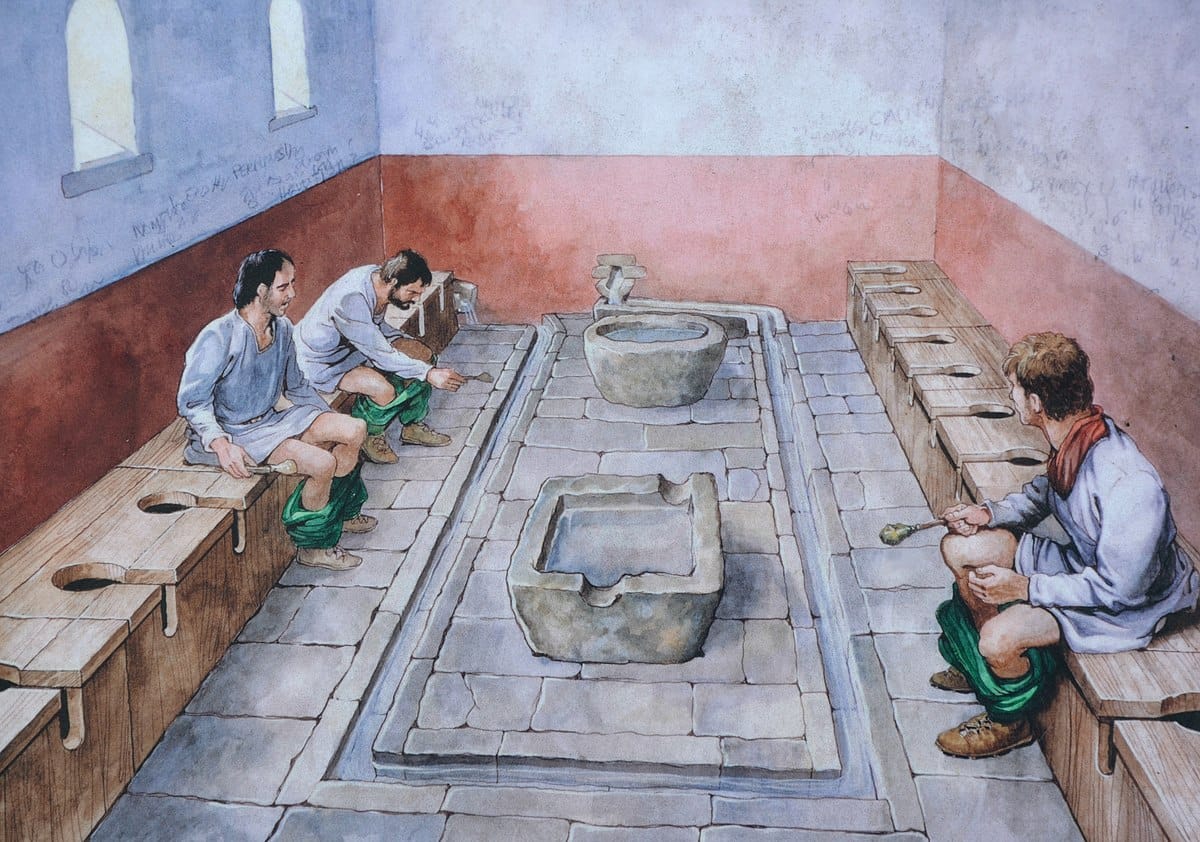

For the Romans, latrines were not just functional spaces but also places for social interaction during defecation. This stands in contrast to modern Western society, where public defecation is largely unacceptable and often illegal in many U.S. towns and cities. These differences in toilet habits highlight the distinct cultural and social norms that have evolved over time.

Urine in Roman Sanitation and Hygiene

Around 2,000 years ago, a high-ceilinged chamber beneath one of Rome’s grand palaces functioned as a communal toilet. This damp space, featuring a bench with around 50 large holes, was likely frequented by some of the lowest members of Roman society. In 2014, archaeologists Ann Koloski-Ostrow and Gemma Jansen had the rare opportunity to examine this ancient toilet on Palatine Hill.

They found that the stone benches were about 43 cm (±17 inches) high —a comfortable seating height— with holes spaced 56 cm (±22 inches) apart, offering little privacy. The sewer beneath was 380 cm (±12.5 feet) deep at its lowest point. The source of water for flushing remains speculative, possibly linked to nearby baths.

Graffiti outside suggested long waiting lines, giving users enough time to leave written or carved messages. The underground location and the basic red-and-white walls further indicated that the space was likely intended for lower-class individuals, perhaps slaves.

In 1913, Italian archaeologist Giacomo Boni excavated the room, but at the time, toilets were considered a taboo subject. As a result, his report appears to have misidentified the holey benches in the space as part of a more elaborate mechanism. Boni speculated that this mechanism might have pumped water and generated power for the palace above, rather than recognizing it as part of a communal latrine. (The secret history of ancient toilets, by Chelsea Whald)

What did Romans do When it was Time for… Number One, or Number Two?

Although we often imagine the ancient world as clean and idealized, the reality of Roman life was far different. The Roman world was dirty, foul-smelling, and full of health hazards. If we were transported back in time, many of us would likely struggle to survive due to exposure to the dirt and diseases that were common in Roman cities, to which we have no immunity.

Human waste often littered the streets and sidewalks, even in the most developed urban areas. The modern Western focus on toilet privacy and hygiene was not a concern for ancient Romans, who had very different cultural attitudes toward these matters.

Ancient Romans had various methods for relieving themselves, depending on the available facilities.

Roman fresco from a latrine, depicting the goddess Isis protecting a man relieving himself. Credits: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0

These ranged from luxurious Roman latrines, where rows of seats were placed over a channel of running water, to more rudimentary setups like chamber pots or open defecation in public spaces. Some homes had simple cesspit toilets with stone or wooden seats.

These facilities were common throughout the Roman world, including in regions like ancient Palestine. The Romans were famous for their sophisticated systems of water supply through aqueducts and waste management via sewers. The "Roman luxury latrine" was a part of this innovation, typically found in bathhouses, where water ran continuously under the seats, washing away waste into nearby sewers.

These latrines were communal, and privacy was not expected, as suggested by Roman writers like Martial, who humorously noted the lack of privacy:

"You read to me as I stand, you read to me as I sit, You read to me as I run, you read to me as I shit."

Most people, however, did not have regular access to such luxury and often used chamber pots, as described by Varro:

"He/she retrieves the Chian amphora of the wealthy for use as a common chamber pot."

Varro, Menippean Satires

The contents of these pots were frequently thrown into the streets, with Juvenal commenting on the dangers of walking below:

"You may be deemed a fool, improvident of sudden accident if you go out to dinner without having made your will."

Juvenal, Satires

Roman cities, such as Pompeii, were designed with features like high curbs and stepping-stones to protect pedestrians from street waste, which was washed away by water from public fountains and directed through gutters into underground sewers. However, in less developed towns, cities, and villages that lacked proper drainage systems, waste often accumulated and flooded the streets during heavy rains.

In the absence of toilet facilities, people relieved themselves in various public spaces, including streets, alleys, staircases, bathhouses, and even tombs. Public urination and defecation were common enough that signs and graffiti were found in cities across the Roman Empire, asking individuals to relieve themselves elsewhere:

Twelve gods and goddesses and Jupiter, the biggest and the best, will be angry with whoever urinates or defecates here.

CIL VI.29848; from the Baths of Titus in Rome

If you shit against the walls and we catch you, you will be punished.

CIL IV.7038; from Regio V at Pompeii

Whoever refrains from littering or pissing or shitting on this street may the goddesses in general favor. If he does not do so let him watch out.

CIL III.1966; from Salona in Croatia

When private toilets were installed in Roman homes, they typically consisted of a stone or wooden seat positioned over a cesspit that wasn’t connected to any sewer or drainage system. These cesspits often doubled as waste disposal areas for household garbage. As a result, toilets were frequently located near kitchens. The contents of cesspits were collected by manure merchants, who then sold the material, known as "night soil," for use as agricultural fertilizer. (What's the poop on ancient toilets and toilet habits?, by Jodi Magness. American school of oriental research)

The Roman Latrines

The Romans were pioneers in adopting toilets as part of their infrastructure. By the first century BC, public latrines became widespread, much like bathhouses, and most urban residents had access to private toilets in their homes. However, archaeologists like Koloski-Ostrow know little about how these toilets functioned and how Romans viewed them.

This is partly because Roman writings on the subject are scarce and often satirical, making interpretation difficult. Roman public latrines resembled earlier Greek designs, with stone or wooden bench seats over sewers. The toilet holes had a keyhole shape, possibly allowing the use of a sponge-tipped stick for cleaning. Small gutters near the seats were likely used to wash these sponges.

Although Roman sewers are often considered an engineering miracle, they were not as widespread or effective as previously thought. Koloski-Ostrow's studies suggest that Roman sewers lacked modern sanitation features like regular aeration or mechanisms to control solid waste buildup. Her research on the Cloaca Maxima, Rome's grand sewer, revealed that it could be easily clogged with silt and required frequent cleaning.

Roman toilets had their shortcomings as well. One major issue was the absence of S-shaped traps in the pipes, which allowed flies easy access to human waste. Environmental archaeologists Mark Robinson and Erica Rowan found numerous mineralized fly pupae in the sewers of Herculaneum, indicating that flies could have spread pathogens to humans through contact with waste.

A well-preserved Roman latrine dating to around the third century A.D., was found in Dougga, North Africa. This latrine was located beside a paved street and built adjacent to a large reservoir. It featured a horseshoe-shaped seat on three sides, standing 43 cm (±17 inches) high and 58cm (±1 foot 11 inches) wide, made of white limestone and faced with polished marble.

The seat had twelve circular openings, each 6 inches in diameter and spaced 58cm (±23 inches) apart. These openings were positioned near the seat's front edge, with narrow 6.4cm (±2½-inch) wide slits running through the seat and the facing slabs. There were footrests provided, and a trough ran in front of the seats.

Beneath the openings was a continuous sloping drain, likely connected to the main street drain, making it a true water-closet. It was probably flushed continuously from the nearby reservoir or periodically by an attendant pouring water into the openings. The street drain was covered with large rectangular stones, with circular access points every few yards, covered by smaller slabs for cleaning or inspection.

In front of the latrine was a large vestibule with a basin supplied by a pipe from the reservoir. While similar to modern public restrooms in some ways, there were notable differences: no partitions between seats, and no evidence of gender separation. It has been suggested that families or guests might have gathered in the latrine, similar to a dining room.

This practice existed in parts of France in the early nineteenth century. The latrine's seat openings were much smaller than modern equivalents, unsuitable for urination, leading to speculation that the vertical slits served this purpose, although it’s unclear whether the urine fell into the drain or in front of the seat.

In large private homes of Imperial Rome, latrines typically emptied into cesspools connected to the sewers rather than directly into the sewer system. This system, if adequately flushed, would have controlled odors effectively—an important consideration given the Romans' attention to cleanliness. The use of cesspools may have acted as a miniature sewage treatment system, reducing waste before it reached the main sewers.

Vitruvius even mentions the use of charcoal in drains, suggesting that the Romans knew about its odor-absorbing properties.

This drainage system, along with abundant water supply and effective waste removal, likely helped protect Rome from typhoid and malaria. While the Romans may not have fully understood the public health implications of their sewage system, its construction was a testament to the engineering and hygienic skill of Roman architects, as parts of it are still in use today. (Annals of medical history. "Roman architectural hygiene", by Chauncey D. Leake)

The Roman Chamber Pots

Chamber pots are large, oval-shaped pottery vessels that were long misidentified in the pottery of the Roman Empire's Danube provinces. Initially, these pots were thought to be storage vessels, large cooking pots, wool baskets, misfired pottery, or even children's bathing tubs. However, in French and Italian specialist literature, these items were correctly identified as 'pitale' or 'pot de chambre,' recognizing their true purpose as chamber pots.

Chamber pots were used for private defecation, and their presence in Roman inns is suggested by graffiti found in Pompeii. One such inscription on the wall of a house indicates that an innkeeper had refused to supply a chamber pot, prompting a disgruntled guest to scratch a complaint onto the wall. This suggests that chamber pots were expected amenities in such establishments:

"We have wet the bed, I admit. We have only sinned, o landlord, if you tell us for what reason there was no [urinal] pot.'

Chamber pots could be made from a variety of materials, including wood, clay, or glass, but also from precious metals like silver and gold, which were typically reserved for the wealthy elite. Ancient literature provides occasional insights into these luxury items, although it mostly highlights the unusual rather than the commonplace. Martial, mentioned chamber pots and the materials they were made from, offering a glimpse into the diverse range of materials used in these everyday objects. However, the mundane nature of most chamber pots means they are seldom noted in such texts:

"An earthenware chamber pot / As I am summoned by the snap of the fingers and the house slave dawdles, / oh, how often the mattress has become my rival!"

"You receive your belly’s load, Bassa, in gold—unlucky gold!—and are not ashamed of it; you drink out of glass. So it costs you more to shit."

Chamber pots were also utilized for children. In Athens, archaeologists discovered a children’s high chair equipped with an integrated chamber pot. Additionally, a similar design can be seen depicted on the interior of an Attic bowl, showing how these combined seating and toilet devices were used for young children in ancient times.

Chamber pots, being small and lightweight, were easily portable. Horace, for instance, mentions five servants accompanying the praetor Tullius from Tibur, carrying a basket of bottles and a portable chamber pot. Literary sources also document the practice of emptying chamber pots from windows onto the streets during the night. The "Digest" Roman law, states that this act was punishable by the authorities. Juvenal, in Satires, adds that one is fortunate if only the contents of a chamber pot are thrown onto them when walking the streets at night.

The Roman fullonica

In the Baths of Mithras at Ostia, a lead pipe from the public urinal channeled fluids directly into a basement corridor, leading to two small underground fullonicae. As likely occurred in towns and cities across the Roman Empire, human waste from urinals was flushed away, only to reappear as an essential industrial cleaning agent. As aforementioned, Roman fullers became well-known for their use of urine to wash woolen cloth.

The practice was so ingrained in Roman society that public urinals and private homes alike collected urine, which was then sold to fullonicae.

The atrium of the Fullonica of Stephanus, one of the most important and complete laundries found in Pompeii, with a tub for washing clothes. Credits: Rafael Jiménez, CC BY-SA 2.0

The Chemistry of Urine

In the first century, Romans used urine in various chemical processes, though the specifics of these processes remain largely unknown. It is suggested that urine was first concentrated to a more useful chemical form by precipitating a crystalline powder known as struvite.

This substance could have been a starting point for several chemical and medical applications relevant to the time. What is known is that decayed urine held significant value, especially for fullers, who collected it from public lavatories and urinals for use in their trade, despite the unpleasant amine odors that must have affected their neighbors.

Emperor Vespasian recognized the importance of decaying urine and taxed it, likely through its association with fullers, although upper-class Romans would have been too embarrassed to be linked with this trade. Fulling, the process of treating woolen cloth, became associated with lower-class labor, and any connection to it was considered a mark of humble origins by the Roman elite.

While it is certain that urine was utilized by Romans in the first century, there is no solid evidence explaining exactly how it was used in chemical processes, nor is there any clear connection to experimental science. Though there are several ancient literary references to the use of decayed urine, practical details about these applications are scarce.

Many sources claim that decayed urine was used for washing clothes because urea, abundant in fresh urine, breaks down into ammonia, a known cleaning agent. However, ammonia is only found in low concentrations in decayed urine, leaving the precise function of urine in cleaning somewhat uncertain.

The advantage of struvite over decayed urine for first-century Romans was that it provided a stable and highly concentrated source of ammonium, allowing for the easy release of potent ammonia fumes. The effects of ammonia from struvite on the human body are significant, even with small amounts. (Ancient Roman urine chemistry, by Michael Witty)

What is Fulling?

Fulling refers to two distinct processes in Roman times: one was akin to modern commercial dry cleaning, where dirty clothes were cleaned, and the other was the industrial finishing of woolen products. Textile historians typically argue that the Roman fullo (fuller) performed both roles simultaneously. It is often said that clothes were "fulled" de tela (from the loom) and ab usu (from use), terms derived from Diocletian's Edict of Maximum Prices from A.D. 301.

Both tasks required similar cleaning products and methods. Clothes were soaked in vats of urine, in the fullonicae, or ancient Roman laundries, which acted as a natural detergent to remove stains and brighten fabrics. Workers, known as fullers, would then trample the garments in these vats to thoroughly clean them, a process akin to a stomping wine press, but for clothes.

Romans discovered that urine, particularly because of its ammonia content, was an effective agent for cleaning and whitening clothes utilized urine as a cleaning fluid.

Ancient Roman latrines, Ostia Antica. Credits: Fubar Obfusco Public domain

The Roman fullo, according to literary sources, was more of a commercial laundryman, a role that likely originated in earlier Mediterranean cultures. Fulling seems to have continued as a laundry service throughout and beyond Roman imperial history.

In the 1st century AD, Emperor Nero introduced the "vectigal urinae" or urine tax, targeting the collection of urine from Rome's public restrooms. This practice was essential for both lower and upper classes, with the collected urine being a crucial component in various industrial processes. The tax was initially abolished but was reinstated by Emperor Vespasian around 70 AD, amid efforts to financially recover from a civil war and an empty treasury.

Vespasian, known for his fiscal strategies that eventually alleviated the empire's debts, reinstated the urine tax as part of a broader taxation scheme to replenish Rome's finances. This initiative included the innovative introduction of public toilets in the Cloaca Maxima system by 74 AD, marking a significant advancement in urban sanitation.

Emperor Vespasian imposed a tax on the collection of urine, giving rise to the phrase "Pecunia non olet" or "Money does not stink," highlighting the value placed on this seemingly mundane byproduct.

'Recycling' Human Waste and Use it Again

The Romans also recognized urine's medicinal properties. It was used as an ingredient in several remedies for ailments ranging from sores and burns to ear infections. Pliny the Elder, documented urine's efficacy in treating wounds and even as a mouth rinse for gum and teeth health. Despite modern sensibilities, the antibacterial properties of urine, particularly in its fresh state, lent some credence to these practices.

"The urine, too, has been the subject not only of numerous theories with authors, but of various religious observances as well, its properties being classified under several distinctive heads: thus, for instance, the urine of eunuchs, they say, is highly beneficial as a promoter of fruitfulness in females.

But to turn to those remedies which we may be allowed to name without impropriety—the urine of children who have not arrived at puberty is a sovereign remedy for the poisonous secretions of the asp known as the "ptyas," from the fact that it spits its venom into the eyes of human beings.

It is good, too, for the cure of albugo, films and marks upon the eyes, white specks upon the pupils, and maladies of the eyelids.

In combination with meal of fitches, it is used for the cure of burns, and, with a head of bulbed leek, it is boiled down to one half, in a new earthen vessel, for the treatment of suppurations of the ears, or the extermination of worms breeding in those organs: the vapour, too, of this decoction acts as an emmenagogue.

Salpe recommends that the eyes should be fomented with it, as a means of strengthening the sight; and that it should be used as a liniment for sun scorches, in combination with white of egg, that of the ostrich being the most effectual, the application being kept on for a couple of hours."

The Romans also used toothpaste formulations based on human urine. Since urine contains ammonia, it was probably effective in whitening teeth. The Greeks, followed by the Romans, enhanced toothpaste recipes by incorporating abrasives like crushed bones and oyster shells to help remove debris from teeth. The Romans further refined these mixtures by adding powdered charcoal, powdered bark, and various flavoring agents to freshen breath.

Beyond personal hygiene, urine played a critical role in the Roman economy, particularly in industries such as tanning and dyeing.

A possible representation of a Roman tanner. Illustration: Midjourney

Tanners used urine to soften and clean animal hides, preparing them for the tanning process. The enzymes in urine helped in breaking down the hides, making them more pliable for subsequent treatment. In the textile industry, urine was employed in the dyeing process. Woolen fabrics were treated with urine before dyeing, as the ammonia helped prepare the fibers to accept dyes more readily, ensuring the colors were vibrant and long-lasting.

In agriculture, urine served as a potent fertilizer. The high nitrogen content was beneficial for soil enrichment, promoting crop growth. Roman farmers collected urine to sprinkle over fields, an early example of recycling waste into a valuable agricultural resource.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: