Marcus Terentius Varro: The Polymath who catalogued the Roman Civilization

Marcus Terentius Varro sought to catalogue Rome itself — its language, gods, customs, and farms. From etymology to agriculture, his vast writings preserved the memory of a people whose strength lay in mixture, tradition, and resilience.

He marched with Pompey, governed estates, and wrote more books than most Romans ever read. Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BCE) was called the most learned of the Romans by Augustine, a man whose vast scholarship sought to catalogue every facet of Roman life—from language and religion to farming and history. Though most of his works are lost, the fragments that remain reveal a restless intellect determined to preserve Rome’s memory at the very moment its Republic was unraveling.

The Life of Marcus Terentius Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro was born in 116 BCE at Reate in the Sabine country, where his equestrian family held large estates. He first studied under L. Aelius Stilo Praeconinus, a scholar deeply versed in Greek and Latin letters and especially devoted to Rome’s history and antiquities. Later he pursued philosophy at Athens under Antiochus of Ascalon, sharpening the intellectual interests that would define his life.

Although drawn to scholarship, Varro did not avoid public duty. He served in Spain during the campaign against Sertorius in 76 BCE, and later fought under Pompey in the war against the Cilician pirates and in the campaign against Mithridates. When civil war broke out, he stood with Pompey, first in Spain and then in Epirus and Thessaly.

After Pompey’s defeat, Varro was pardoned by Caesar, who entrusted him with organizing a great public library of Greek and Latin works. Yet following Caesar’s assassination, his fortune turned again: Antony placed him on the proscription lists, his villa at Casinum was seized, and his personal library was destroyed. Varro himself escaped execution only thanks to loyal friends who hid him until Octavian’s protection could be secured. The final years of his life were spent in peace, devoted entirely to writing, until his death in 27 BCE at the age of eighty-nine.

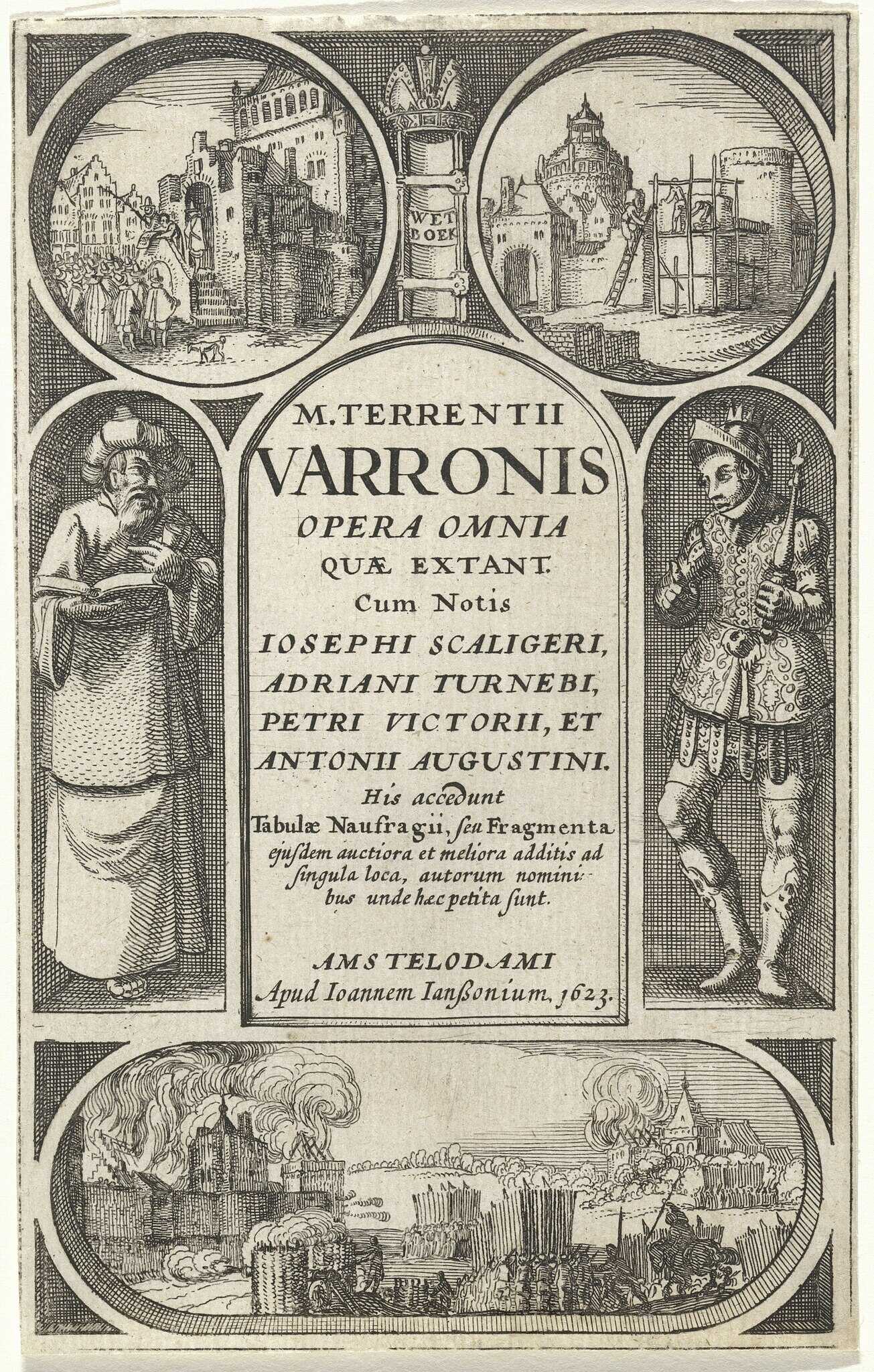

Over his long career, Varro wrote tirelessly. Ancient sources credit him with seventy-four works amounting to some six hundred and twenty books, covering almost every field of knowledge: agriculture, grammar, Roman history and antiquities, geography, law, rhetoric, philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, education, literature, drama, satire, poetry, oratory, and letters.

Of this vast output, only one work has survived complete — the three books of On Agriculture. His On the Latin Language, originally twenty-five books, survives only in part, with Books 5–10 extant and even these with many gaps. The rest of his writings reach us only in fragments scattered through later authors.

Among his linguistic works were On the Antiquity of Letters, dedicated to the poet Accius; On the Latin Language, addressed to Pompey; and several technical treatises on orthography, poetic meters, and the principles of analogy and anomaly in Latin usage. He also compiled the Disciplinae, an encyclopedic account of the liberal arts in nine books, beginning with grammar. (Varro on the Latin language, by Roland G. Kent, edited by T.E Page, E. Capps, W., H., D., Rouse)

“Varro was a philosopher and a historian, a fine soldier and a fine general, and perhaps for these reasons was proscribed as an enemy to monarchy.

His intimates were ambitiously seeking to take him in and contending with one another to do so, [but Q. Fufius] Calenus won out and kept him in a country house, where Antony used to stop when he would travel.

Yet no slave of Varro himself or of Calenus revealed his presence.

Appian, Bella Civilia 4.6.47

Varro’s Works and Intellectual Legacy

Varro, lived through one of the most transformative periods of Roman history: the late Republic, its collapse, and the rise of the Empire. A large portion of his long life was dedicated to scholarship, producing an extraordinary body of work. Ancient sources attribute to him hundreds of volumes and dozens of titles, covering both prose and poetry.

His writings-as already mentioned- extended across genres and subjects, from satire and literary criticism to studies on language, history, and antiquarian themes, as well as technical treatises on agriculture, geography, law, philosophy, medicine, architecture, and the seven Greek liberal arts. Varro’s vast productivity made him an essential reference for later authors of the imperial and late antique periods, including Gellius, Plutarch, Charisius, Augustine, Nonius, and Servius.

Yet only a fraction of his writings survive, most of them in fragmentary form.

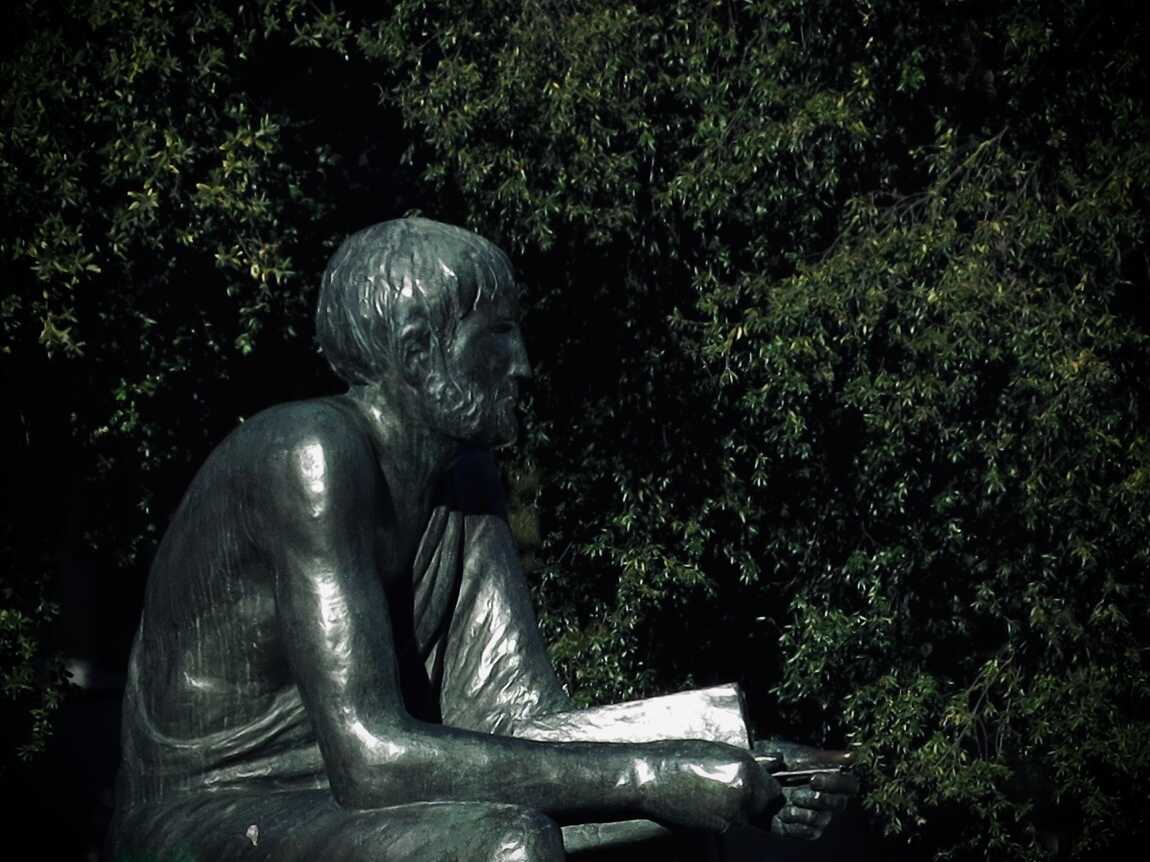

Marcus Terentius Varro and his thoughts. Credits: Alessandro Fornara, CC BY-SA 4.0

For several works, however, enough remains to reconstruct approximate dates of composition, which in turn allows scholars to link specific texts to the political and historical circumstances of their time. These connections suggest that Varro’s intellectual output was shaped by the challenges of his era. His historical, antiquarian, and linguistic writings, in particular, can be seen as contributions to an ongoing debate about the identity of the Roman people, reflecting his effort to situate Roman culture within a broader ideological framework.

He didn’t see antiquarianism and linguistics as separate pursuits. To him, the study of language was inseparable from the study of Rome’s culture. When he investigated the origin of words, he wasn’t just being pedantic: he was digging into the roots of Roman identity. He described etymology as a kind of archaeology — “unearthing” what had been buried by time. Time, he said, brings vetustas (age), which obscures meaning like dust over an inscription. Yet with effort, the truth can be recovered, unlike oblivio (forgetfulness), which erases it completely.

The Weight of Crisis

Why did Varro suddenly devote himself to these massive works in the 40s BCE? Maybe it wasn’t just because he finally had the leisure after years of campaigning with Pompey. Maybe It was because Rome itself was unrecognizable. Varro once imagined a man in his satire, The Sixty-Year-Old, who fell asleep as a child and woke up half a century later:

“When I returned to Rome, I found nothing there of what I had left fifty years before.”

Varro’s Menippean satire Sexagessis

The city had changed so much that even its morals seemed foreign. Varro’s generation had lived through the Social War, when Italy’s allies turned against Rome demanding citizenship. They had witnessed Sulla’s dictatorship, Caesar’s wars, and the chaos of rival strongmen. Rome itself seemed fractured, its identity unclear. Who was Roman now? Who belonged? These were not abstract questions. They pressed on the daily politics of citizenship, belonging, and loyalty.

Varro’s answer was radical for his time. He argued that Rome had always been mixed. The Romans were not a pure people but a blend of many. In his great Antiquities, he wrote that the earliest Romans descended from different stocks — Pelasgians, Aborigines, Aeneas’ Trojans — and were bound together in “brotherly kinship.”

He gave special weight to the Sabines, his own people from Reate, insisting that many Roman gods and customs came from them. The word multa (a fine), he said, was Sabine. So were deities like Feronia, Minerva, Salus, Fortuna, and Fides. Everyday words too, from crepusculum (twilight) to supparus (a woman’s dress), showed Rome’s Sabine roots. But he did not stop at Italy. He admitted that Latin carried Greek, Etruscan, and even Gallic words.

“Not all words in our language come from the vernacular,”

he explained; some are:

“foreign or hybrid, coined here from a foreign model.”

He gave examples: sagum (a cloak) from Gaul, miles (soldier) from Etruscan, and many others. Latin was, in his eyes, the product of centuries of exchange.

Varro was not ashamed of this. Quite the opposite: he stressed that Romans took from others through imitatio — not slavish copying, but adopting, adapting, and improving. He described Roman ancestors dining sitting down, a custom borrowed from Greeks and Cretans. Far from weakening Rome, this capacity to absorb and reshape was the secret of Roman greatness.

For Varro, then, the Latin language itself was a mirror of Roman identity. It was not pure or untouched but layered, mixed, and evolving. He even imagined that from the very founding of the city, Rome had welcomed outsiders. Some believed he hinted at the asylum of Romulus, where refugees and wanderers were gathered into the first citizen body. Rome began as a mixture — and that mixture was a source of vitality, not corruption.

He did not do this work only for curiosity’s sake. He openly said he feared that Rome’s gods and traditions might:

“perish, not by the attack of enemies, but by the neglect of its citizens.”

He described his books as a shelter for them:

“rescuing them as if from a collapsing building, and giving them refuge in memory.”

His scholarship was a civic duty: to save Rome’s culture from decay, to record its traditions before they were lost. Cicero praised him for this. In one dialogue, he has a character say that Varro’s books made Romans feel at home again, no longer:

“wandering like foreigners in their own city.”

Through his antiquarian and linguistic studies, Varro gave his fellow citizens a map of who they were.

The Mirror of Rome

Varro’s scholarship was not backward-looking nostalgia. It was a present project, a way of redefining Roman identity when the Republic was collapsing. He held up a mirror to his people, showing them that they had always been a mixture — Latins, Sabines, Etruscans, Greeks, Gauls — and that their strength lay in this layered heritage. By preserving this truth in writing, he hoped Romans might recognize themselves again. (Rome in the mirror: Varo's quest for the past, for a present goal, by Federica Lazzerini, University of Oxford)

Varro turned scholarship into civic service. He wasn’t cataloguing the past for its own sake, but to remind Romans of who they were — not a pure lineage, but a people born of many traditions, bound together by memory.

Varro and the World of Agriculture

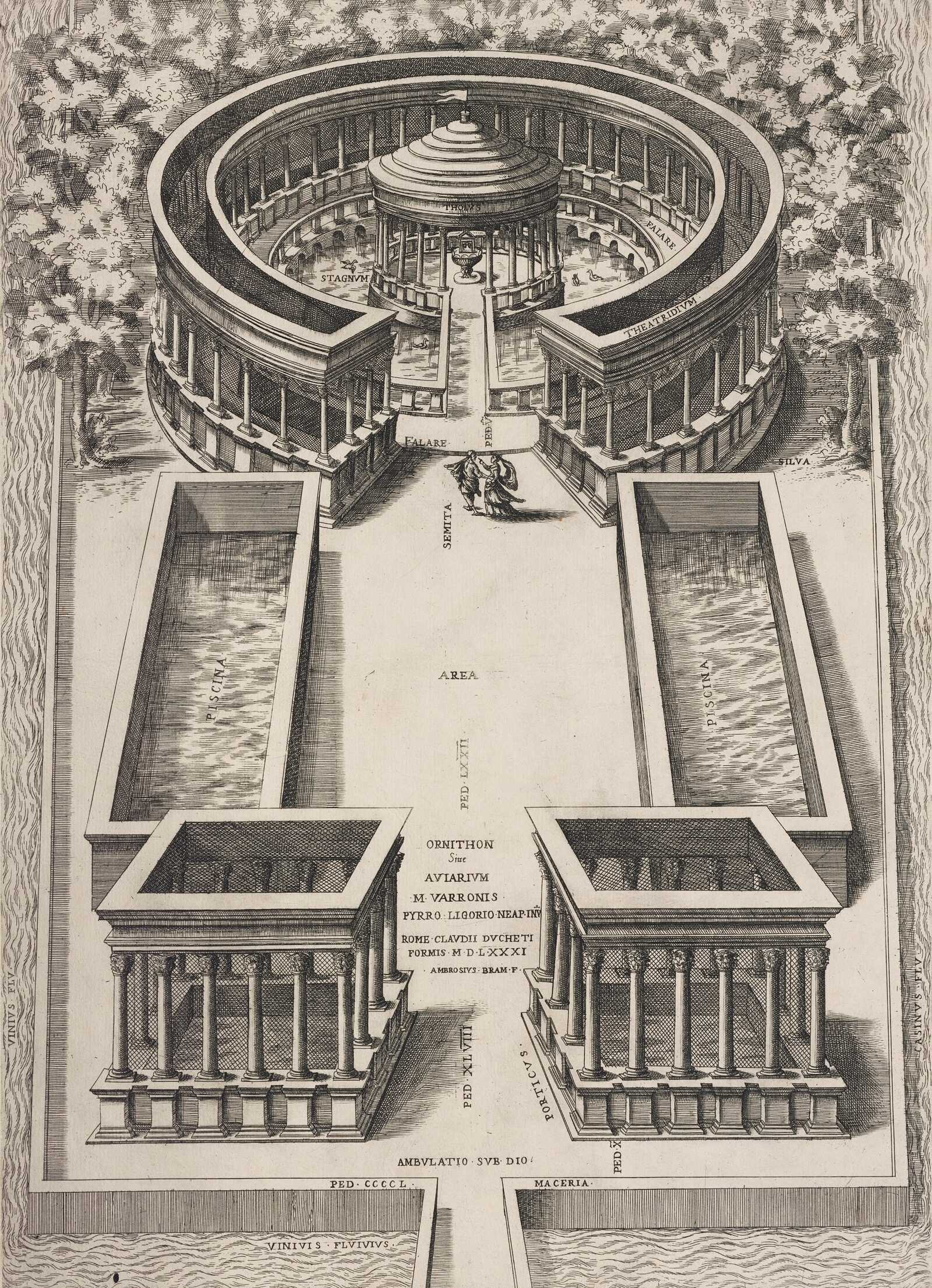

In the final years of the Republic, when civil war and political chaos seemed to uproot everything, Varro turned to the land. His three-book On Agriculture is often described as a farming manual, but it is much more than advice on vines, olives, or livestock. Beneath its surface, the work reflects on Rome’s political struggles, its cultural identity, and even its survival.

The treatise is framed as conversations held on country estates, far from the turmoil of the Forum. Different voices debate topics like crop rotation, cattle breeding, or villa management, but woven into their exchanges are reflections on civic life. Farming is never only about farming. To cultivate the land is also to cultivate the state. Just as fields must be cleared, planted, and tended, so too must a community be educated, disciplined, and ordered.

Again and again, agriculture becomes a metaphor for civic virtue. Weeds are like corruption, irrigation like wise government, a balanced estate like a balanced society. To neglect the land is to invite sterility; to neglect the Republic is to invite decay. The soil, Varro reminds his readers, responds only to those who work it with diligence:

“The land does not betray those who care for it.”

At times the dialogue borders on satire. The speakers are not ideal philosophers but real landowners, with their quirks and biases. Their conversations carry humor, irony, even complaint. Yet behind the laughter lies something serious: a warning that Rome itself risks ruin if it forgets the lessons of agriculture — moderation, patience, and respect for tradition.

By the time On Agriculture was written, Varro had already endured exile, proscription, and the bloody rivalries of Rome’s leaders. He had seen libraries burned and estates confiscated. The choice to write about farming was not accidental. It was an attempt to find stability in a world where politics had turned destructive. Farming was Rome’s oldest foundation, the work of the ancestors. To write about it was to remind Romans that their strength lay in the countryside, in the toil of fields and the order of estates.

In Varro’s hands, the farm becomes more than an economic unit. It is a moral model, where household order reflects civic order, and rural labor embodies the values that made Rome strong. The villa is almost a miniature Republic: the master as leader, the workers as citizens, the land as the common good. If Rome was to survive, it had to be managed like a well-run estate — with foresight, fairness, and discipline.

So while the text does offer practical instructions — how to prune vines, when to sow grain, how to raise poultry — these are never the whole story. Behind every piece of advice is a larger message: Rome must learn to cultivate itself as carefully as it cultivates the land. Agriculture is a mirror for politics, and the farmer’s diligence is the model of the citizen’s duty. (Varro the agronomist: Political Philosophy, Satire, and Agriculture in the Late Republic, by Grant A. Nelsestuen)

Varro’s Lists: Preserving Complexity

Varro’s way of writing often took the form of catalogues — long lists of gods, words, and disciplines. On the surface they seem neat and orderly, but they reveal just how unruly Roman tradition really was. In religion, for instance, his Antiquities laid out a dizzying number of deities, each responsible for a stage of life or labor, from planting seeds to harvesting crops.

Later generations mocked this excess as confusion, yet for Varro it was an honest reflection of reality: Roman life was complex, so its gods were too. The same pattern appears in his Disciplinae, a survey of the nine liberal arts.

Grammar, rhetoric, mathematics, and astronomy were neatly lined up, yet within each field knowledge spilled over with variety and contradiction. Rather than hide this disorder, Varro preserved it, showing Romans that their heritage was layered, plural, and worth remembering in all its tangled detail. (Varro and the disorder of things, by Katharina Volk)

Varro and the Life of the Roman People

Among Varro’s many lost works was one especially precious: De vita populi Romani — On the Life of the Roman People. Unlike the historians who told of wars, triumphs, and the rise and fall of leaders, Varro set out to capture something different: the everyday fabric of Roman culture. His subject was not the march of armies but the habits, morals, and traditions that gave shape to Roman life.

Fragments show his fascination with the ordinary and the ritualistic. He described how the Roman day began, what customs marked the turning of the seasons, and which practices bound citizens together. This was history as memory: a cultural record of who the Romans were, not just what they did. One surviving line conveys his aim clearly:

“The life of the Roman people is best known through its customs.”

Religion and morality formed a large part of this project. Varro catalogued rites and ceremonies that governed marriage, death, agriculture, and civic duty. He paid attention to the rhythms of festivals, the laws that regulated family and property, and the rituals that maintained the bond between people and gods. These details may have seemed small, but for Varro they were the true essence of Rome. The work also carried a moral undertone:

Varro was not only preserving customs for their antiquarian charm; he was holding them up as a mirror.

Closeup of a statue of ancient Roman scholar Marcus Terentius Varro in his birthplace, Rieti. Credits: Alessandro Antonelli, CC BY 3.0

Romans could look back at these traditions to measure how much they had changed — or strayed. His antiquarian method, assembling fragments of language, ritual, and law, was in service of cultural memory. He was recording not just for curiosity but for identity. Most of De vita populi Romani is lost, but later authors hint at its richness.

Nonius preserves references to old Roman words and expressions, Augustine cites Varro’s observations on morality and religion, and scattered fragments suggest that he traced practices back to the earliest days of the Republic. Through these glimpses, we see a vast project that must have stood as a companion to his Antiquities — one treating the gods, the other the people who worshipped them. (The Annals of Varro, by H. A. Sanders. The American Journal of Philology)

Varro and Slavery: The “Talking Tools” Debate

One of the most quoted lines linked to Varro is the unsettling description of slaves as instrumenta vocalia — “talking tools.” In On Agriculture, he divides the equipment of a farm into three types: mute tools like wagons and ploughs, semi-vocal tools like oxen, and vocal tools like slaves.

On the surface, it sounds brutally dismissive, reducing human beings to objects. Yet the context shows something more complicated. The remark is part of a neat classification scheme, likely adapted from Greek sources, that sorted everything on the farm into categories. It was not a moral reflection but a practical shorthand.

Still, the fact that slaves could be grouped with animals and implements at all reveals how deeply slavery was woven into Roman life. Even a man of Varro’s learning could speak of human beings primarily in terms of their usefulness. And yet, elsewhere, Varro acknowledges the skills and individuality of enslaved workers, suggesting he did not see them as mere tools in every respect.

The “talking tools” line may not tell us what Varro truly believed about slavery, but it tells us a great deal about the world he lived in — a society where the humanity of slaves was easily obscured by the demands of agriculture and estate management. (Did Varro Think that Slaves were Talking Tools?, by Juan P. Lewis)

Marcus Terentius Varro was more than a scholar; he was Rome’s archivist. In a world torn by war and political collapse, he set down in writing the language, customs, gods, and practices that defined his people. Much of it is lost, but what survives shows his vision: that Rome’s greatness was not a matter of purity or power, but of memory — the ability to gather, preserve, and make sense of a complex past. Through Varro, Rome learned to see itself.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: