Crassus: The Wealthiest Man in History was Roman

Known as the richest man in Rome, Crassus amassed an almost mythical fortune through a combination of shrewd investments, calculated risks, and, some would argue, ruthless opportunism.

Often cited as the wealthiest individual in Roman history, Marcus Licinius Crassus’s fortune was legendary. His wealth was estimated to be equivalent to the entire budget of the Roman treasury.

Crassus’s wealth primarily came from real estate speculation, silver mines, and his role in the slave trade. His infamous use of a private fire brigade that would offer to buy burning buildings at a reduced price before extinguishing the fire exemplifies his ruthless approach to wealth accumulation.

From buying up burning properties at bargain prices to financing political campaigns, Crassus turned wealth into power in a society where influence was often measured in denarii.

But Crassus was more than a tycoon; he was a political mastermind, a member of the famed First Triumvirate, and a man whose ambitions ultimately led him to the desolate sands of Carrhae. His story is one of dazzling wealth, audacious ambition, and a tragic end that underscored the limits of even Rome’s richest citizen.

In 2014, The Washington Post examined the comparative wealth of historical figures like Marcus Crassus against modern billionaires like Bill Gates. They drew on Branko Milanovich's book, "The Haves and Have-Nots", to estimate Crassus' wealth at 200 million sesterces, suggesting an annual income of 12 million sesterces based on a 6% interest rate. However, considering the 12% interest rate set by Sulla in 88 BC and Crassus' notorious financial acumen, a more likely income could be 24 million sesterces per year.

Branko Milanovic, a top inequality economist employs a method that equates wealth to the ability to purchase human labor, highlighting the vast difference in labor costs between ancient Rome and modern Western societies due to the competition from slave labor in Rome. While Milanovich uses an average Roman income of 380 sesterces for his calculations, this method suggests Crassus' income was equivalent to the earnings of 32,000 average Romans at a 6% rate, or 64,000 Romans at a 12% rate.

Contrasting this with Bill Gates in 2005, when his wealth was estimated at $50 billion and annual income at $3 billion, Gates' wealth relative to the GDP per capita was approximately 75,000 times. Using Milanovich’s 6% return calculation, Gates appears more than twice as wealthy as Crassus. However, adjusting for the 12% rate, Gates' wealth still surpasses Crassus but not by as wide a margin.

Business Insider in 2011 quoted economist Peter Bernstein, suggesting that if converted appropriately, Crassus' wealth could be as much as $220 billion, rivaling the wealthiest individuals of all time.

A Revaluation of Rome's Richest Man

T.J. Cadoux, in his work “Marcus Crassus: A Revaluation, from Greece & Rome, Second Series,” challenges the traditional negative image of Marcus Licinius Crassus, often portrayed as a secondary figure in Roman history. Crassus has long been remembered as a greedy, inept politician and military leader whose wealth overshadowed his other contributions.

Cadoux argues that this view, popularized by historians like Theodor Mommsen, (a highly influential German historian, jurist, and politician, widely regarded as one of the greatest scholars of Roman history) is overly simplistic and ignores important facets of Crassus’ career and character.

Crassus’ Reputation in Roman History

Crassus is frequently dismissed as an unremarkable and unattractive figure compared to Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great. Textbooks have traditionally characterized him as a "money-grubber" and a subordinate player in the First Triumvirate, with his political and military aims seen as selfish and unsuccessful.

For example, Mommsen describes Crassus as "a merchant" who lacked honor and served only to balance the power between Caesar and Pompey. Similarly, Pelham's (a British historian and academic who specialized in ancient Roman history) work reduces him to a vain figure with limited intellect who acted as a willing tool of Caesar. Cadoux contends that such sweeping judgments do not hold up when reexamining the available evidence.

The Personality of Crassus

Contrary to popular belief, Crassus was not a dull or disagreeable individual. Both Cicero and Plutarch provide glimpses of his character, describing him as courteous, approachable, and dignified. His speeches were noted for their simplicity and structure, and he was well-versed in history and the philosophy of Aristotle.

“He pleased people also by the kindly and unaffected manner with which he clasped their hands and addressed them.

For he never met a Roman so obscure and lowly that he did not return his greeting and call him by name.

It is said also that he was well versed in history, and was something of a philosopher withal, attaching himself to the doctrines of Aristotle, in which he had Alexander as a teacher.

This man gave proof of contentedness and meekness by his intimacy with Crassus; for it is not easy to say whether he was poorer before or after his relations with his pupil.

At any rate he was the only one of the friends of Crassus who always accompanied him when he went abroad, and then he would receive a cloak for the journey, which would be reclaimed on his return.

But this was later on.”

Plutarch, The Parallel Lives

While it is true that Crassus amassed vast wealth, his methods were no more questionable than those employed by other elites of his time, including Pompey, who was nearly as wealthy. Importantly, Crassus used his wealth as a tool for political power rather than hoarding it out of greed. For example, he lent large sums to his friends, including the financially insolvent Julius Caesar, without charging interest.

This generosity underscores that his ambitions were primarily political rather than material.

Marcus Licinius Crassus Marble Bust. Credits: Affegass, Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

"However, Crassus was generous with strangers, for his house was open to all; and he used to lend money to his friends without interest, but he would demand it back from the borrower relentlessly when the time had expired, and so the gratuity of the loan was more burdensome than heavy interest.

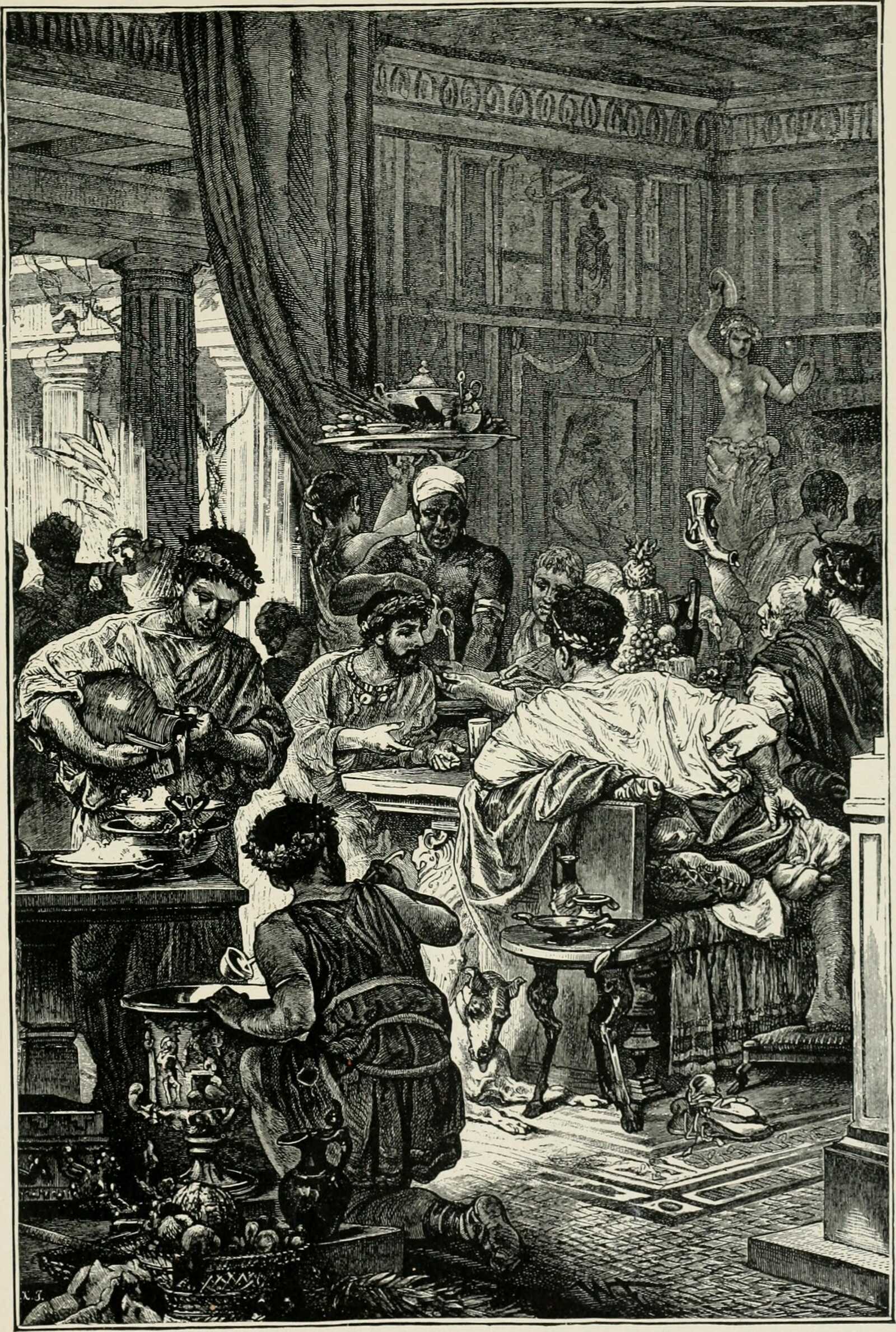

When he entertained at table, his invited guests were for the most part plebeians and men of the people, and the simplicity of the repast was combined with a neatness and good cheer which gave more pleasure than lavish expenditure."

Plutarch, The Parallel Lives

Crassus as a Soldier

Crassus is often remembered for his disastrous campaign against the Parthians, but Cadoux suggests this singular failure unfairly overshadows his earlier military successes. As a young man, Crassus demonstrated exceptional bravery and leadership in the civil war of 83–82 BCE, playing a critical role in Sulla’s victory at the Colline Gate.

Later, as a praetor, Crassus successfully suppressed Spartacus’ slave revolt when other commanders had failed, defeating the insurgents decisively in battle. Plutarch notes that Crassus fought "as a good general should," exposing himself to personal risk during the final confrontation with Spartacus. Despite Pompey’s attempt to claim credit for ending the revolt, public recognition of Crassus’ achievement made him a rival to Pompey in the political arena.

Crassus as a Politician

Crassus’ political career reveals him as a shrewd operator who pursued power with relentless determination. While self-advancement was his primary motive, this ambition was not unique among Roman nobles of the late Republic. Crassus’ methods were innovative for his time, as he relied heavily on his wealth to build a network of clients and subordinates.

Unlike his peers, he did not align with either the reformers, or the conservative faction in the Senate. Instead, he positioned himself as a power broker, leveraging his financial resources to influence others holding imperium.

From 67–62 BCE, Crassus worked tirelessly to counter Pompey’s growing influence. He supported various figures and initiatives, such as Caesar, Piso, and Catiline, to build a coalition capable of challenging Pompey. While some of his schemes were thwarted by Cicero’s diligence, Crassus remained a persistent and resourceful strategist.

His eventual partnership with Caesar and Pompey in the First Triumvirate marked the culmination of these efforts. Contrary to the traditional view that Crassus was merely a "makeweight" in this alliance, Cadoux argues that he was initially the leading partner, using his wealth and influence to secure the cooperation of Caesar and neutralize Pompey.

Crassus and Caesar

Cadoux challenges the notion that Caesar dominated the First Triumvirate from the outset. At the time of the Triumvirate’s formation in 60 BCE, Caesar was still a relatively junior figure compared to Crassus, who had already held the consulship and censorship.

While Caesar’s eventual success in Gaul transformed the power dynamics, it was Crassus who initially supported Caesar’s rise, providing financial backing and political alliances. This relationship allowed Crassus to maintain influence over Caesar, at least until the latter’s military victories made him an independent force.

The Parthian Campaign

Crassus’ decision to lead a military campaign in Parthia in 53 BCE marked a turning point in his career. Plutarch suggests that Crassus sought military glory to rival Caesar’s achievements in Gaul, but Cadoux points out that this ambition was not unusual for Roman nobles.

Unfortunately, Crassus’ campaign was marked by strategic errors and bad luck. He underestimated the Parthians, relied on poor advisors, and ultimately met his death in a treacherous encounter under a flag of truce. While this failure has come to define Crassus’ legacy, Cadoux urges readers to consider his earlier accomplishments and the broader context of his career.

Marcus Licinius Crassus was more than just Rome’s richest man. He was a complex figure whose political ambition, military service, and personal character merit a more balanced assessment. Though his Parthian campaign ended in disaster, his contributions to Roman politics and military history were significant.

Crassus was a man of considerable influence and ambition, embodying both the strengths and flaws of the Roman nobility in the late Republic. Cadoux’s revaluation offers a more nuanced understanding of a figure who has often been overshadowed by his more famous contemporaries.

Wealth, Power, and the Struggle for Supremacy in Ancient Rome

Summarising the above, Marcus Licinius Crassus, often remembered as one of the wealthiest individuals in Roman history and a key member of the First Triumvirate, has a legacy shrouded in complexities. His political maneuvering, military ambitions, and immense fortune made him a central figure in the late Republic. Despite his significant influence, gaps in historical records and his premature death during the Parthian campaign have left many aspects of his life open to interpretation.

His early life was marked by tragedy. The purges of Marius and Cinna claimed the lives of his father and brother, shaping his pursuit of power and survival. Forced into hiding in Spain for fear of political retribution, he eventually emerged as a staunch ally of Sulla, aligning himself with the dictator during the latter’s return to Italy.

This alliance allowed Crassus to play a pivotal role in military campaigns, notably at the Battle of the Colline Gate, where his contributions were instrumental to Sulla’s victory.

A gravure dubbed Porta Collina, or The Colline Gate. Credits: The British Library, Public domain

Crassus’s legendary wealth became one of his most defining characteristics. He accumulated his fortune through a combination of strategic real estate acquisitions, investments, and exploitation of the proscriptions under Sulla, which redistributed wealth from political opponents to loyalists.

Despite his wealth and influence, Crassus’s political and military career was not without its challenges. His rivalry with Pompey began during the campaigns against Spartacus’s slave revolt. Although Crassus was the commander who decisively ended the rebellion, Pompey’s arrival at the final stages allowed him to claim partial credit, overshadowing Crassus’s achievements. This rivalry persisted into their joint consulship in 70 BCE, where disagreements over policy highlighted their competing ambitions.

Crassus’s role in the First Triumvirate alongside Caesar and Pompey was crucial but often understated. While the alliance allowed him to achieve key political objectives, such as the renegotiation of tax contracts favorable to the equites (Roman knights), it was fraught with tension, particularly between Crassus and Pompey.

Caesar’s growing military successes in Gaul further complicated the balance of power within the triumvirate, prompting Crassus to seek a command of his own.

Part of a print dubbed Gaul Surrenders to Caesar. Credits: Sicko Atze van Dijk, CC BY 2.0

Determined to restore his military reputation and assert his dominance, Crassus undertook a campaign against the Parthians. This decision, as aforementioned proved disastrous. His forces suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE, where Crassus himself was killed. This failure not only marked the end of his life but also the unraveling of the First Triumvirate, as the fragile alliance could not withstand the absence of its wealthiest member.

His legacy and modern depiction in films like Stanley Kubrick‘s Spartacus, has often been overshadowed by his wealth and his association with more prominent figures like Caesar and Pompey. Historical accounts frequently emphasize his greed, ambition, and military missteps, but a closer examination reveals a more nuanced figure. Crassus was a skilled politician who understood the power of financial leverage and the importance of alliances in a volatile political landscape. His ability to navigate the complexities of Roman politics, despite numerous setbacks, highlights his resilience and strategic thinking.

In reevaluating Crassus, it becomes clear that he was more than a wealthy opportunist. He was a pivotal player in the transition from Republic to Empire, using his wealth and influence to shape the course of Roman history. His failures, particularly in Parthia, have perhaps unfairly overshadowed his successes. Crassus’s story is one of ambition, adaptability, and the relentless pursuit of power in an era defined by political upheaval and shifting allegiances. (Marcus Licinius Crassus, by Kathleen Toohey)

The Tycoon Who Dreamed of Conquest

The first tycoon of ancient Rome was also one of its most infamous failures. Had Marcus Licinius Crassus died in 54 BCE, he might have been remembered quietly as Rome’s wealthiest man, a pioneer in modern finance and political maneuvering, the ruthless victor over Spartacus’s slave rebellion, and a key figure in Julispartac enduring image of Laurence Olivier’s portrayal in Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus.

Instead, Crassus embarked on the ill-fated military campaign against Parthia, venturing into the arid borderlands of modern-day Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. The campaign culminated in the catastrophic Battle of Carrhae, where he suffered his crushing defeat, losing not only his army but also the sacred eagle standards of his legions.

His death became the stuff of dark legend: storytellers claimed his severed head was used as a stage prop in a Greek tragedy in a city deemed too uncivilized by Roman standards for such art, and his mouth was said to be stuffed with gold—a grim metaphor for his unquenchable greed.

Crassus’s defeat left an indelible mark on the Roman psyche. Decades later, the emperor Augustus considered the recovery of Crassus’s lost eagle standards one of his most significant achievements, commemorated by Rome’s greatest poets and sculptors. Crassus’s life, a unique combination of exceptional success and dramatic failure, continues to raise enduring questions about the complex relationship between wealth, ambition, and power.

Crassus’s Parthian Gamble

Delving into the details of what happened with the Parthians, in the summer of 54 BCE, Crassus stood on the cusp of his most ambitious and ultimately tragic endeavor: the eastern campaign against Parthia. At the age of sixty, Crassus, clad in his red cloak, meticulously prepared his army of seven legions to cross the Euphrates and extend Rome’s dominion into the vast and mysterious East.

Known for his shrewdness in financial and political dealings, Crassus approached this military campaign with the same detailed precision that had defined his life’s work. His plans were as grand as they were risky, aiming to bring the riches and renown of the Parthian Empire into Rome’s fold.

Crassus’s life had been deeply rooted in Rome, both geographically and symbolically. Unlike other Roman aristocrats, he seldom traveled abroad or derived pleasure from his vast Italian estates. Instead, he focused his efforts on amassing wealth and consolidating power within Rome’s three square miles.

Through real estate ventures, loans to indebted politicians, and a shrewd understanding of human capital, Crassus became synonymous with wealth and influence. As we mentioned, he financed multiple political campaigns, disrupted traditional power structures, and acted as a behind-the-scenes force in the corridors of Roman authority.

The campaign against Parthia, however, was designed to redefine Crassus’s legacy. Having lived much of his life in the shadows of his contemporaries—Pompey, the celebrated general, and Julius Caesar, the rising political and military star—Crassus sought to secure military glory on par with his peers.

While he had crushed the Spartacus slave revolt in 71 BCE and played a vital role in Sulla’s rise to power decades earlier, these achievements were overshadowed by the grandeur of Pompey’s eastern conquests and Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul. This expedition, stretching Rome’s reach farther east than ever before, was Crassus’s attempt to cement his name in Roman history.

Crassus’s preparations underscored his meticulous nature. He ensured his legions were well-equipped and supplied, employing tactics of coercion, bribery, and negotiation to secure local allies and resources. However, his unfamiliarity with the Parthian adversary, King Orodes, and the geographical challenges of the desert frontier revealed the limitations of his strategy.

Crassus’s reliance on his son Publius, a decorated commander under Caesar in Gaul, highlighted the family’s aspirations for shared glory.

A Swiss medal depicting the death of Crassus' son Publius at the hands of the Parthians. Credits: Mesamong from Getty Images by Canva, LouisAragon CC BY-SA 2.5, Composition by Roman Empire times

Publius’s arrival with Gallic cavalry was eagerly awaited, as these light horsemen were critical for countering the formidable Parthian cavalry. Despite his meticulous planning, Crassus faced significant challenges. His troops were less experienced compared to those of Caesar and Pompey, and doubts lingered about his ability to lead effectively after a two-decade absence from the battlefield.

Nevertheless, Crassus’s confidence remained unshaken.

He envisioned himself as a conqueror akin to Alexander the Great, with plans to send victory reports to Rome from legendary cities like Babylon and Susa. The prospect of immense wealth and power drove his ambitions, as he aimed to surpass the achievements of his rivals and secure an enduring legacy.

Yet, Crassus’ aspirations were not solely driven by personal glory. He sought to elevate his family’s standing, ensuring a prosperous future for his sons and silencing detractors who criticized his avarice and questioned his reputation.

His marriage to his brother’s widow, Tertulla, was emblematic of his pragmatic approach to consolidating wealth and influence, though rumors of infidelity and greed often dogged their union. His son Publius, admired for his military prowess and political promise, represented the next generation of Crassus’s ambition.

As he prepared to face the Parthians, his campaign symbolized a convergence of Rome’s militaristic ethos, political ambition, and the pursuit of wealth. The expedition was fraught with risks—both logistical and strategic—but his resolve remained steadfast.

He sought not only to conquer Parthia but also to redefine his identity, transitioning from Rome’s wealthiest financier to its preeminent leader. This bold gamble for imperial glory would ultimately culminate in one of the most dramatic and tragic episodes of Roman history, as the Battle of Carrhae would reveal the limits of ambition, and the perils of overreach. (Crassus. The First Tycoon, by Peter Stothard)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: