How Did the Romans Conquer Greece?

From Illyria to Corinth, Rome conquered Greece not in a day but through decades of alliances, wars, and diplomacy. Yet while the legions won the land, Greek culture won Rome — transforming its conqueror into its greatest disciple.

Greece was no prize to be claimed overnight, yet by the mid-2nd century BCE it lay under Roman rule. How did a republic rooted in central Italy come to dominate the cradle of philosophy, drama, and democracy?

The story begins not with a single decisive battle, but with decades of intervention, alliance, and manipulation—first in the periphery, then at the heart of Greek affairs. Rome’s path to conquest was paved through her wars with Macedon, her interventions in the Greek leagues, and, ultimately, the crushing of the Achaean League in 146 BCE. It was a conquest by degrees—legal, military, and cultural—one that left Greece politically subjugated yet culturally undefeated.

Prelude to Conquest: Warnings from Naupactus

In the decades before Roman legions ever landed in Greece, the Hellenistic world was already showing cracks. The successors of Alexander the Great—Macedon, the Seleucids, and the Ptolemies—had carved his empire into rival kingdoms whose constant wars left the Greek mainland divided and exhausted.

Independent city-states like Athens, Sparta, and Corinth had long lost their old strength, surviving now through shifting alliances and fragile leagues such as the Aetolian and Achaean. Polybius, writing a century later, saw that the summer of 217 BCE marked a turning point.

At the Conference of Naupactus, the Aetolian leader Agelaus warned the Greeks that “clouds were gathering in the west.” He meant the rise of a new power—Rome—whose wars against Carthage would soon bring its gaze toward the eastern Mediterranean. His prophecy proved correct.

Rome’s first encounter with the Greek world had come earlier, in 229 BCE, when Roman armies crossed the Adriatic to curb Illyrian piracy that threatened Italian traders. What began as a limited expedition created a precedent: Rome now claimed a protector’s role in Balkan affairs. Each time Rome withdrew its forces, it left behind a deeper dependence. The Greek states, torn by their own rivalries, began to appeal to Rome for arbitration, inadvertently legitimizing Roman authority.

Meanwhile, Macedon under Philip V dreamed of restoring its supremacy. The young king ended the Greek “Social War” of 220–217 BCE abruptly after learning of Hannibal’s victory at Lake Trasimene, persuaded by his advisor Demetrius of Pharos that Rome’s distraction offered a rare opportunity. Philip’s plans to move westward into Illyria and Italy brought the two powers into collision. From that moment, Greek independence would slowly give way to Roman intervention, first in Illyria, then across the Greek mainland itself.

Across the Adriatic: Rome’s First Step Toward Greece

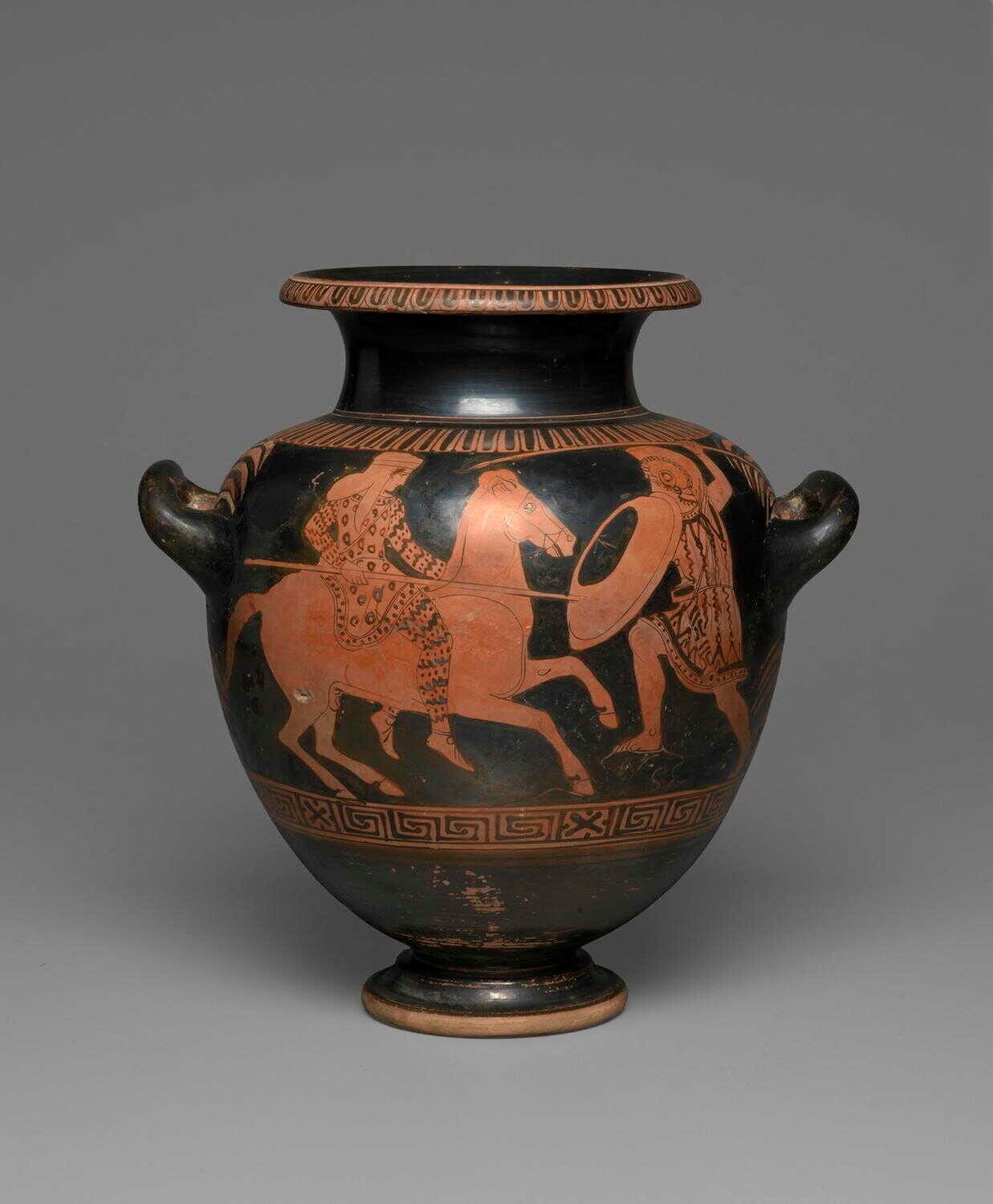

In 229 BCE, Rome crossed the Adriatic for the first time. What began as a campaign against piracy became the Republic’s opening move into the Greek world. Illyrian raiders under Queen Teuta had long menaced Adriatic trade and attacked cities allied to both Greece and Italy.

When Roman envoys sent to negotiate were killed, the Senate acted with characteristic resolve, dispatching a fleet of two hundred ships and twenty thousand soldiers—nominally to punish the Illyrians, but in truth to project power beyond the Italian peninsula.

The campaign was swift. Roman forces captured Corcyra, Apollonia, and Epidamnus, driving the Illyrian garrisons north and forcing Teuta into submission. She was forbidden to sail armed ships south of Lissus or to harm Rome’s allies.

The expedition created a bridgehead on the eastern Adriatic and gave Rome its first taste of Greek politics. The Illyrians were subdued, but their defeat brought the Republic face to face with the fractured Greek world, where every alliance was a prelude to intervention.

The First Illyrian War did not conquer Greece, but it set a precedent. Rome had acted as an arbiter across the sea, and Greek states—seeking protection rather than fearing domination—sent envoys to thank the Senate. They did not yet realize that, in celebrating Rome’s victory, they were greeting their future master.

Rome and the Macedonian Wars: The Freedom of the Greeks

By the early second century BCE, Rome’s influence across the Adriatic had ceased to be accidental. The Republic, victorious in Illyria and hardened by years of war with Carthage, began to look east with a new sense of purpose. To many in the Senate, the Hellenistic kingdoms were unstable, arrogant, and in need of restraint — the same justification Rome had used to subdue Italy.

In Macedonia, King Philip V sought to restore the old prestige of Alexander’s house. His alliance with Hannibal during the Second Punic War made him Rome’s natural enemy. The first clash, the First Macedonian War (214–205 BCE), ended inconclusively, but it introduced Rome to the tangled politics of Greece. The Aetolian League, once wary of Rome, now courted its protection against Macedon; others followed. Every new alliance drew the Greeks deeper into dependence.

Peace brought no stability. When Philip attacked cities along the Aegean and in Asia Minor, Pergamon and Rhodes appealed to Rome for help. The Senate, wary but tempted by opportunity, sent legions east once again. The Second Macedonian War (200–197 BCE) unfolded across Thessaly and northern Greece, pitting the Macedonian phalanx against the flexible Roman legion.

In 197 BCE, the two armies met at Cynoscephalae — “the Dog’s Heads” — a range of rolling hills near modern Larissa. There, Titus Quinctius Flamininus, a young Roman commander fluent in Greek and sympathetic to Hellenic culture, crushed Philip’s army. The defeat ended Macedon’s bid for supremacy and exposed the vulnerability of every Greek state.

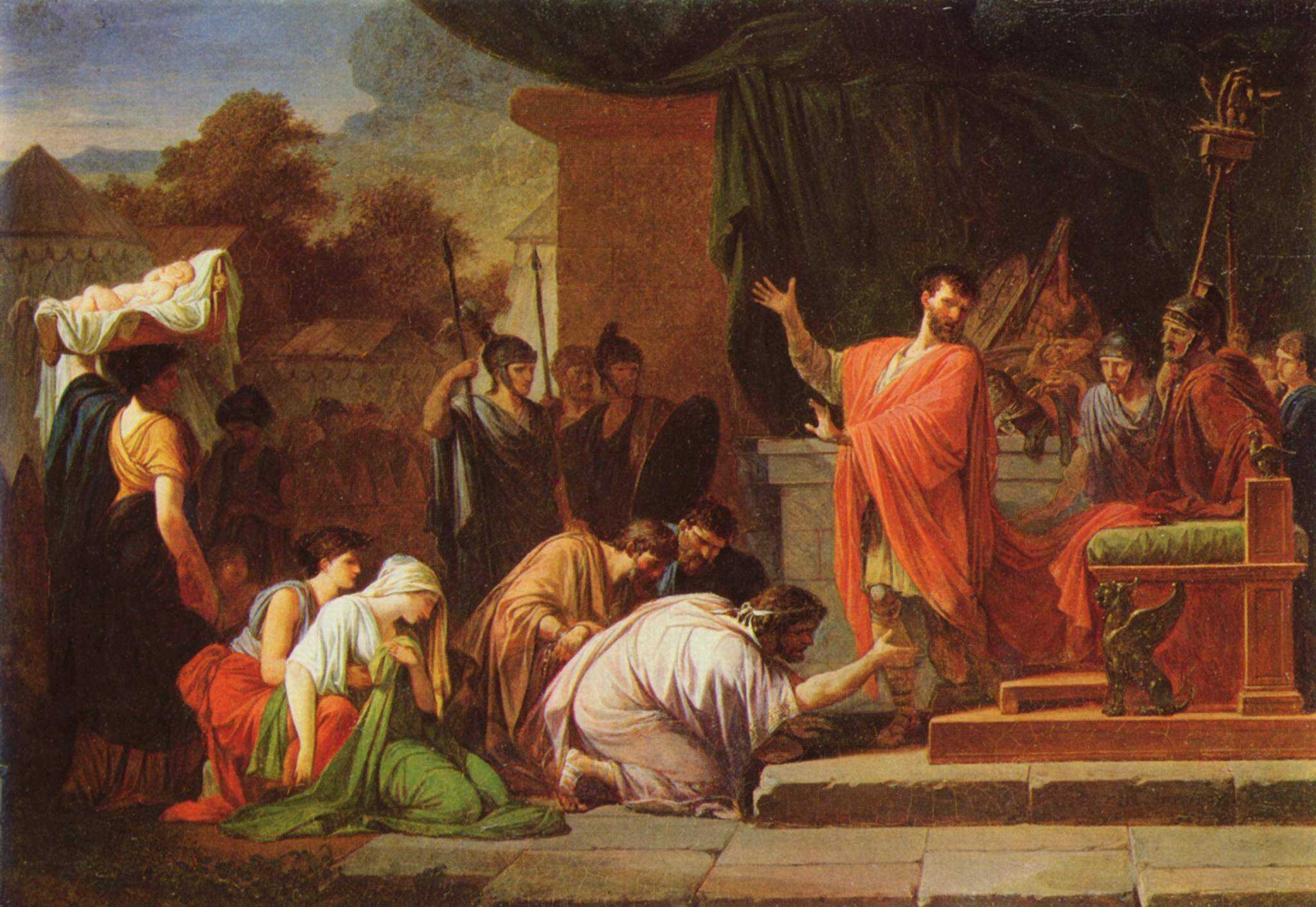

At the Isthmian Games two years later, Flamininus addressed the assembled crowd. The herald proclaimed:

“The Senate and people of Rome, having overcome King Philip and the Macedonians, now restore freedom to the Greeks — freedom to govern themselves, to enjoy their own laws, and to pay no tribute.”

The response was thunderous. Ancient sources describe the crowd erupting in shouts so loud they startled the birds from the sky. Yet behind this act of magnanimity lay the first clear form of Roman control. By claiming to give freedom, Rome defined the terms of it. Greek gratitude soon turned to dependence, and the language of liberty became the instrument of empire.

The False Dawn: Antiochus III and the Greek Revolt

The peace proclaimed by Rome after Cynoscephalae proved fragile. Many Greeks quickly realized that “freedom” under Roman protection was freedom only in name. Among them, resentment simmered within the Aetolian League, which had once allied with Rome but now saw itself eclipsed by more compliant neighbors.

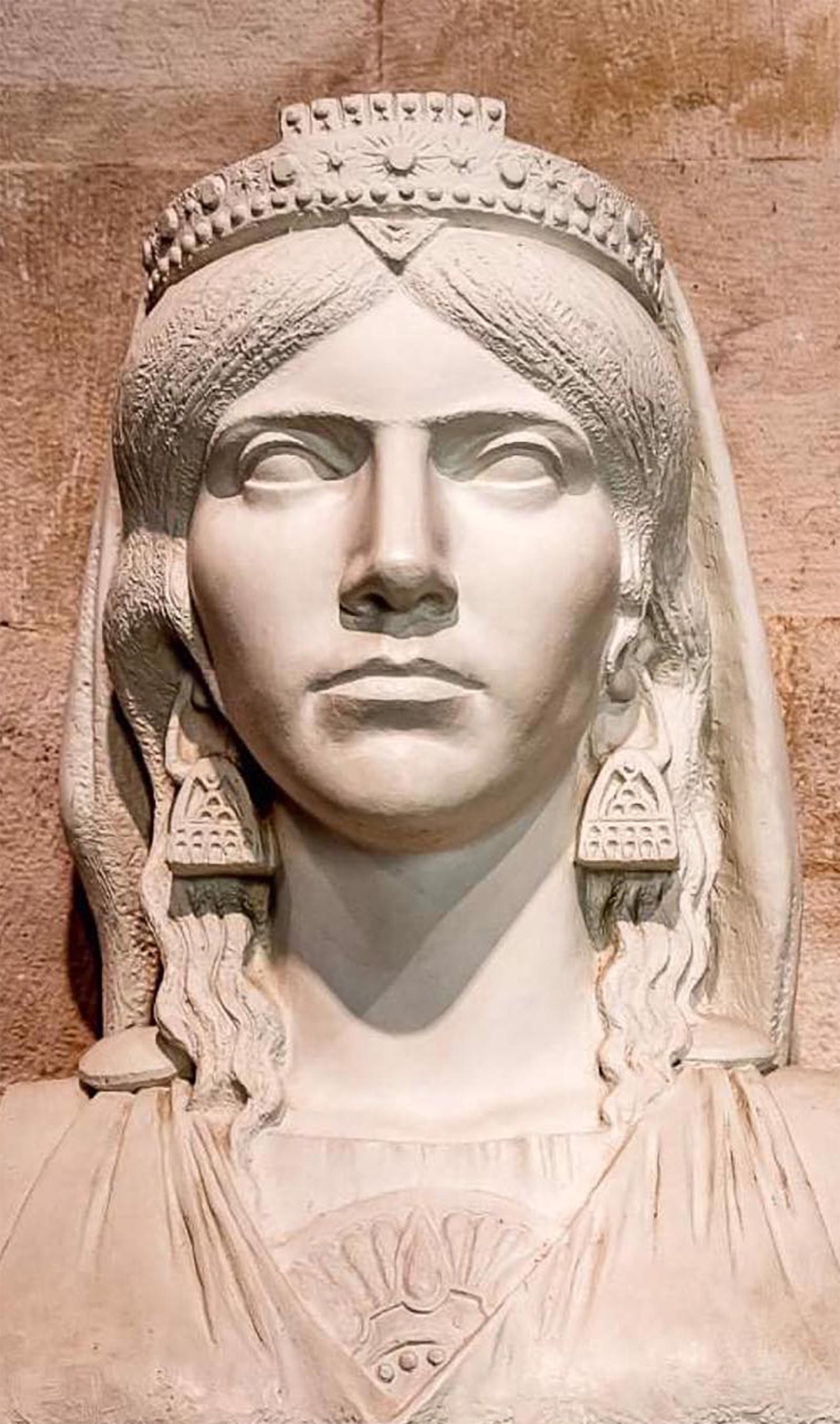

Seeking to restore its influence, the League turned to a new savior from the east — Antiochus III, king of the Seleucid Empire. Antiochus, a descendant of one of Alexander’s generals, had long dreamed of restoring his dynasty’s former reach. Victorious in campaigns through Asia Minor and beyond, he appeared to many Greeks as a champion of Hellenic independence.

In 192 BCE, answering Aetolian pleas, he crossed the Aegean with a modest force and landed in Greece, where he proclaimed that his mission was to “liberate the Hellenes.” Yet few answered his call. The cities hesitated, remembering the ruin that past wars had brought, and Rome’s diplomats swiftly branded him an intruder.

The Roman Senate, alarmed but confident, sent Manius Acilius Glabrio to confront him. In 191 BCE, the two forces met at Thermopylae, the mountain pass immortalized by Leonidas and his Spartans. Antiochus fortified the ancient position and invoked the spirit of past Greek resistance, but his army — outnumbered and poorly supported — collapsed before the disciplined Roman advance.

The defeat was total. Abandoning his troops, Antiochus fled back across the Aegean, his brief campaign in Greece reduced to legend.

Sculpture of Antiochus III (The Great) at Louvre. Public domain

For the Greeks, the episode was a cruel awakening. The “liberator” had failed, and with him vanished the last illusion that foreign kings might restore their autonomy. Rome, now undisputed master of the Greek mainland, pressed eastward in pursuit. The dream of resistance flickered out, replaced by uneasy acceptance that the balance of power had shifted for good.

Rome Across the Aegean: The Defeat of Antiochus the Great

Antiochus III’s flight from Greece did not end Rome’s advance; it merely shifted the battlefield eastward. The Senate was determined to crush the Seleucid threat once and for all. While Antiochus regrouped in Asia Minor, Rome forged new alliances with Pergamon and Rhodes, maritime powers that feared Seleucid expansion as much as the Romans did.

Their fleets joined the campaign, marking the first great coalition between Rome and the Hellenistic East. In 190 BCE, the combined Roman and allied armies under Lucius Cornelius Scipio (known as Scipio Asiaticus), brother of Scipio Africanus, crossed into Asia Minor.

Facing them near Magnesia, close to Mount Sipylus, was a vast Seleucid force—war elephants, scythed chariots, and heavy cavalry drawn from across the eastern provinces. The battle was brief but decisive. When the chariots panicked and broke formation, the Roman legions advanced with their usual discipline, enveloping the Seleucid flanks. Antiochus fled the field, leaving tens of thousands dead.

The following year, the Treaty of Apamea (188 BCE) ended the war. Antiochus surrendered all territories west of the Taurus Mountains, handed over his fleet and elephants, and agreed to pay an enormous indemnity spread over twelve years. The Seleucid Empire, once the mightiest successor to Alexander, was reduced to a shadow of its former self.

The victory made Rome the dominant power of the eastern Mediterranean without annexing a single province. Instead, she ruled through “friends and allies”: Rhodes, Pergamon, and smaller client kingdoms that owed their position to Roman favor. This new system of indirect control allowed Rome to expand her influence while avoiding the costs of occupation. Greek freedom remained the official slogan, but it was Rome that now defined the terms of peace and alliance.

Rome’s Grip Tightens on Greece

The defeat of Antiochus III left Rome unrivaled in the eastern Mediterranean, but conquest was followed by restraint. The Senate had no appetite for direct rule over Greece; its states were to remain “free,” provided they aligned with Roman interests. Thus began a new kind of domination—one exercised not through occupation but through influence.

Greek envoys thronged to the Senate in search of favor, and their rival petitions offered Rome the perfect excuse to intervene whenever useful. The Greeks, by appealing to Rome as arbitrator, unwittingly legitimized her supremacy. Even minor disputes were now judged in the Forum rather than in Delphi or Corinth.

Rome’s favored allies—Rhodes and Pergamon—acted as proxies, enforcing Roman policy while preserving the illusion of independence. Yet this arrangement bred resentment. In Greece, the Aetolian League was dismantled, the Achaean League grew restless under supervision, and Macedon, humbled but intact, quietly rebuilt its strength. Beneath the surface calm, ambitions and grievances were stirring again.

By mid-century, Greek politics had become a chessboard on which Rome moved the pieces. Her officials seldom stayed long, her legions seldom marched—but the threat of both hung constantly in the air. Freedom had become conditional, and the language of alliance was indistinguishable from that of subordination. Rome ruled Greece at a distance, and distance made her power feel both inevitable and irreversible.

Macedonia’s Last Stand

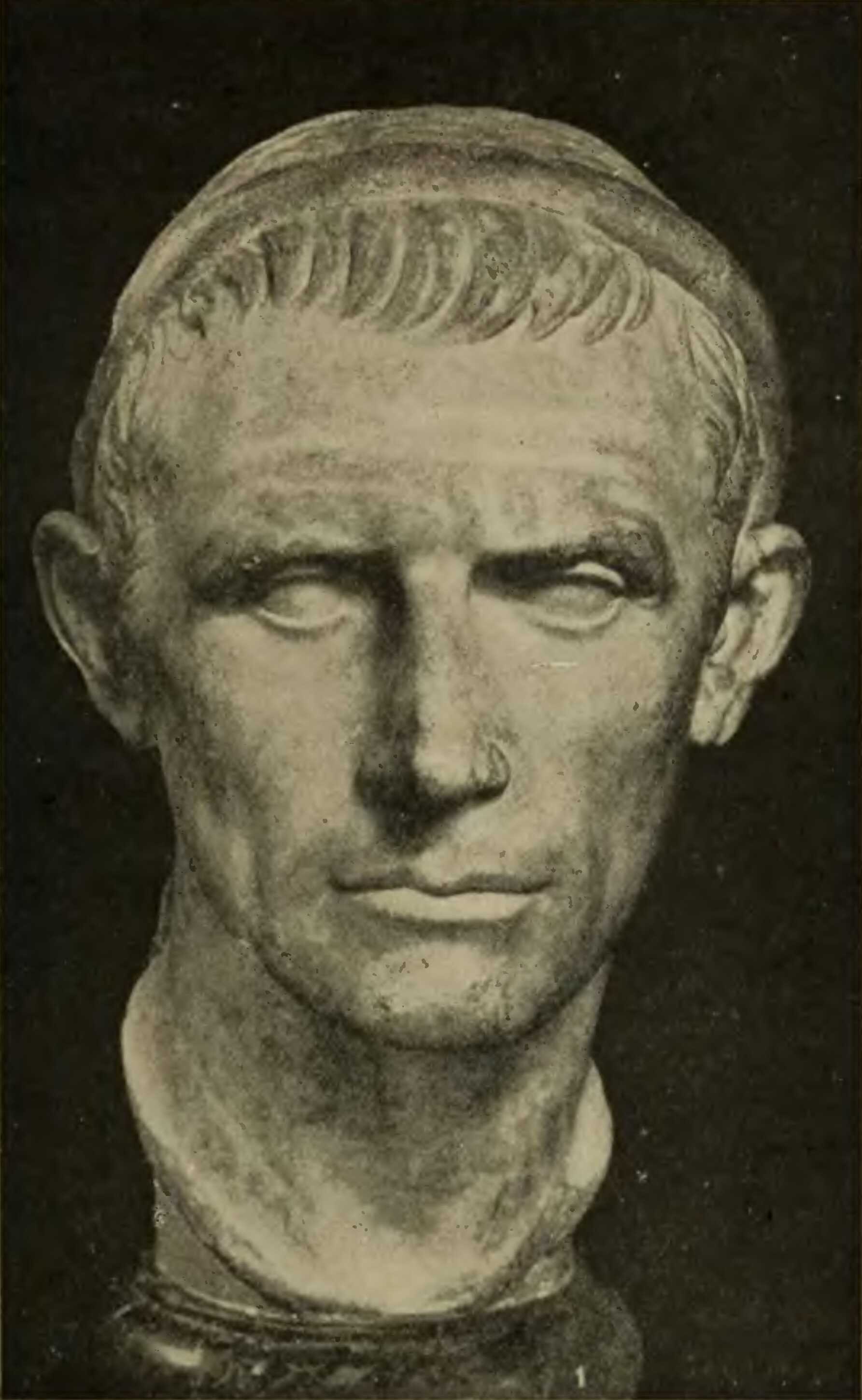

In the uneasy calm that followed the defeat of Antiochus, Macedonia once again became the center of Greek politics. Its king, Perseus, son of Philip V, inherited a kingdom that had been weakened by Rome’s earlier wars but not destroyed.

Intelligent and cautious, Perseus aimed not to provoke Rome directly, but to restore Macedonian dignity and leadership among the Greeks. His vision was of unity under Macedon’s guidance — a revival of Hellenic independence that would not openly defy Roman power but might, in time, replace it.

Perseus pursued diplomacy before war. He sought alliances with Epirus, Boeotia, and the Achaean League, married Laodice, daughter of the Seleucid king, and extended friendly overtures to Rhodes and Pergamon. Yet every move, however cautious, alarmed the Senate. The Romans had learned to see strength in others as a potential challenge to their authority.

When Pergamon’s king Eumenes II, a loyal Roman ally, denounced Perseus in a speech before the Senate, his words sealed Macedonia’s fate. Rome accused Perseus of plotting to dominate Greece and prepared for war. The conflict that followed — the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BCE) — would decide the region’s future.

Perseus began well, winning early skirmishes and earning the admiration of Greek observers who saw in him a disciplined, just ruler compared to Rome’s overbearing presence. Yet his caution proved fatal. "He preferred hesitation to boldness", and the opportunity to strike decisively never came.

Rome responded with overwhelming force. The veteran commander Lucius Aemilius Paullus, father of the future conqueror of Corinth, took command of the Roman army. In 168 BCE, the two sides met near Pydna, on the plains of northern Greece.

The Macedonian phalanx initially pressed forward with its iron wall of spears, but the uneven ground broke its formation. The Roman legions, fighting in flexible maniples, slipped through the gaps and slaughtered the encircled Macedonians. By nightfall, Perseus had fled; his kingdom was finished.

The defeat at Pydna ended not only the Macedonian monarchy but the dream of Greek autonomy. Rome divided Macedonia into four client republics, forbade intermarriage between them, and imposed tribute. The day of kings was over; in their place stood the imperium of Rome.

Rome’s Unquestioned Supremacy

The victory at Pydna in 168 BCE ended more than a war—it ended the balance of power in the Greek world. Macedonia, once the empire of Alexander, was reduced to fragments under Roman oversight. The Senate divided the country into four republics, each forbidden to trade or intermarry with the others, ensuring that unity—and rebellion—would never return.

The monarchy was formally abolished, and the royal treasury was shipped to Rome, where the influx of Macedonian silver “changed the texture of Roman politics itself.” While Roman soldiers were ordered to show restraint, their commanders moved decisively to extinguish any lingering resistance.

Perseus, captured while seeking refuge on Samothrace, was paraded through the streets of Rome in Aemilius Paullus’ triumph—a living symbol of conquered royalty. Thousands of Macedonian soldiers and sympathizers were enslaved, and leading citizens from Greek states that had wavered during the war were summoned to Italy for questioning. Few ever returned.

Rome now stood as the arbiter of all Greek affairs. Her policy of indirect control continued, but the tone had changed: behind the courteous language of friendship lay the certainty of command. The Senate dictated settlements between quarrelling leagues, drew new borders, and decided who might rule and who must yield. To the Greeks, freedom was again proclaimed—but this time it came from conquerors who no longer felt the need to pretend.

Across the Aegean, the message was clear. The Seleucids and Ptolemies, watching from afar, understood that the Republic would brook no rival. Macedonia’s fall marked the end of kingship as a credible force in the Hellenistic world. What remained was diplomacy conducted on Roman terms, and a Mediterranean orbiting around a single center of power.

The Architecture of Control

After Pydna, Rome no longer needed to prove her dominance; she simply exercised it. The Republic’s authority now extended from the Atlantic to the Aegean, and the Greek world, though still nominally free, was woven into a structure of power the Romans called the imperium Romanum — the “Roman command.”

The Senate, cautious of governing lands directly, perfected the art of ruling through dependence. In Greece and Asia Minor, Rome avoided the appearance of empire, preferring to govern through allied kings, leagues, and city councils. Yet every decision of consequence — from boundary disputes to dynastic successions — passed through Rome’s hands. In effect, Rome could now achieve more through a letter than once through an army.

The new order rested on deterrence. Greek states remembered what happened to those who challenged Roman policy, and that memory maintained obedience more effectively than legions. Still, the Senate did not hesitate to act when loyalty wavered. In 150 BCE, Macedon briefly rose again under Andriscus, a pretender claiming descent from Perseus.

His rebellion was crushed within a year, and in its aftermath Macedonia became Rome’s first formal province in the East — a precedent soon followed by others. The material benefits of victory flooded into Italy. Plundered wealth and enslaved captives transformed Rome’s economy and reshaped its society.

Yet the Republic itself, was not immune to the spoils of conquest: the influx of riches deepened inequality and corrupted the civic ideals that had once defined it. Rome had mastered the world but was beginning to lose mastery over itself.

For the Greeks, the new reality was clear. Their cities retained their laws, temples, and games, but decisions of war, peace, and policy no longer belonged to them. The imperium Romanum had been built not through annexation, but through consent, exhaustion, and inevitability. By the mid-second century BCE, the Mediterranean world was, in essence if not in name, a Roman one.

The Limits of Tolerance: Corinth, 146 BCE

Tensions inside the Achaean League finally snapped in the mid-second century BCE. Resentment at Roman arbitration, border rulings, and the punishment of dissenters hardened into open defiance. When Achaean forces clashed with Roman troops, the outcome was never in doubt. In 146 BCE the consul Lucius Mummius defeated the League and entered Corinth.

The city was sacked, its treasures seized, and its people sold into slavery. The League was dissolved. Rome did not annex Greece wholesale—it rarely needed to—but Corinth’s destruction signaled the end of meaningful Greek autonomy. From then on, even the appearance of independence depended on Roman forbearance.

Conquered but Unbroken

After Pydna, the Greek world entered a new age — one of dependence, but also of endurance. Politically, freedom was gone; culturally, Greece remained Rome’s teacher. Though the legions had triumphed in battle, the conquerors looked eastward for philosophy, art, and education. The result was a paradox: Rome’s empire expanded, yet its civilization grew ever more Greek.

Across the mainland and the islands, daily life resumed under the new order. Cities administered themselves, festivals continued, and philosophers debated in the gymnasia as they had for centuries.

Athens, diminished but still radiant, became a finishing school for Roman youth; Rhodes taught oratory and diplomacy; Delphi, though silent in politics, retained its sacred prestige. The Achaean and Aetolian Leagues, relics of an older age, faded into ceremonial councils — tolerated, so long as they posed no threat.

Wealth flowed westward, but influence moved east. Greek artists, architects, and scholars filled Roman homes, palaces, and libraries. “The empire that ruled Greece found itself ruled by Greek culture.” Stoicism, sculpture, and theater all took on new life in Roman form, blending discipline with refinement. Even Roman literature, from Ennius to Horace, spoke with a Greek accent.

Yet beneath this cultural harmony lay memory and melancholy. The Greeks remembered their independence, even as they instructed their conquerors. Pride survived conquest, reshaped into a different kind of authority — that of intellect and tradition. The dream of political autonomy had died, but the legacy of Hellenism endured, transforming the civilization that had subdued it.

By the close of the second century BCE, Rome stood supreme, and Greece, though no longer sovereign, remained its spiritual capital. In victory, the Romans had inherited not just land but identity — for to rule the Greek world was, inevitably, to become part of it. (Taken at the flood. The Roman Conquest of Greece, by Robin Waterfield)

From Illyria’s coasts to the ruins of Corinth, the Roman conquest of Greece was never a single campaign but a gradual submission of one civilization to another. The legions triumphed by strength, but the Greeks endured through spirit, intellect, and art.

When Rome claimed dominion, it also claimed a heritage far older and richer than its own. In the centuries that followed, the conqueror and the conquered would become inseparable — Rome wearing the laurels of Greece, and Greece, though subdued, forever shaping the soul of Rome.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: