How did Romans Flood the Colosseum for Naval Battles in the Arena?

Were naumachiae actually held in the Colosseum? How did the Romans flood the arena to stage a naval battle?

It’s believed that the Emperor Titus hosted the first Colosseum naval battle (naumachia, from the Greek ‘ναυμαχία’) in 80 AD to celebrate the amphitheater’s grand opening. These events were similar to gladiatorial fights in that they were fought to the death, but participants were typically prisoners of war or condemned criminals reenacting famous historical sea battles.

Water Spectacles of Early Imperial Rome

Dio dedicates nearly a full chapter to describing the water-based displays included in Titus' hundred-day celebration for the inauguration of the Flavian Amphitheatre in A.D. 80 (referred to as θέατρον [κυνηγετικόν], and later widely known as the Colosseum).

Despite certain limitations as a historian, Dio’s detailed account, especially when presenting challenging specifics, is not to be dismissed lightly. His description of Titus' aquatic spectacles notably differentiates between the Flavian Amphitheatre and the Stagnum Augusti, presenting an intricate set of details that highlight the logistical and symbolic complexities of these displays:

“Large numbers of individuals fought in single combat, whereas others competed against each other in groups in infantry and naval battles.

For Titus had suddenly filled this same theatre with water, and he had brought in horses and bulls and other domesticated animals that had been taught to do in water everything that they could do on land.

He also brought in people on ships; they engaged in a naval battle there representing the Corcyreans versus the Corinthians. Others gave a similar display outside the city in the grove of Gaius and Lucius, which Augustus had once excavated for this purpose.

There, too, on the first day - once the lake in front of the images had been covered with a platform of planks and wooden stands had been erected around it - there was a gladiatorial display and a slaughter of wild beasts; on the second day there was a horse-race, and on the third day a naval battle involving three thousand men, followed by an infantry battle: the 'Athenians' conquered the 'Syracusans' (these being the designations the men fought under), landed on the island, and stormed and captured a wall that had been built around the monument.”

The questions that arise from such a description vary in nature, from a purely logical and feasibility perspective, as well as understanding the era’s logistics and limitations.

- Is it plausible to believe that aquatic spectacles were truly staged within the Flavian Amphitheatre?

- Could the arena be effectively flooded?

- How did animals play a role, and was there enough space for naval battles?

- What motivated the recreation of historical battles, especially when the venue seemed inadequate for such displays?

- Furthermore, if the Flavian Amphitheatre could accommodate aquatic events, why replicate them at the Stagnum Augusti or install a platform there to host spectacles more suited to the amphitheatre or circus?

- And why reenact a historical event, like the Athenian failed attack on Syracuse in 414 B.C., only to stage an outcome at odds with real history?

These questions are rooted in a Roman mindset quite distinct from our modern perspective: an enthusiasm for inventive and elaborate spectacles that, in Roman culture, often involved blending theatrical elements with mortal combat. This theatrical drive is most evident in public executions that used well-known myths as a basis for dramatic retellings. The same flair for drama extended to grand-scale combats, like Julius Caesar’s 46 B.C. triumph, where series of animal hunts culminated in a mass military engagement, complete with a detailed “set” of two camps replacing the typical turning posts for added realism.

“Beast-hunts were held over five days, and at the end a battle was fought involving two contingents, each comprising five hundred infantry, twenty elephants, and thirty cavalry.

So that there would be more space for the fighting, the turning-posts were removed and replaced by two camps facing each other”

Suetonius

Suetonius doesn’t clarify if this particular battle was presented in a historical framework. However, there is evidence of one such staged scenario, where Emperor Claudius captured a model British town on the Campus Martius, recreating the British king’s surrender:

"On the Campus Martius too he staged the storming and sacking of a town in an imitation of real warfare, culminating in the surrender of the British kings, and he presided in his campaigning cloak."

It’s plausible that the "Britons" in the spectacle were actual British captives, allowing Roman spectators to relive the Claudian campaign, of which the emperor was particularly proud. By the late Republic, gladiatorial combat had become a popular form of public entertainment, showcasing the skills of highly trained fighters. Mass battles are a natural progression from this, shifting the focus from individual prowess to the grandeur of large-scale combat. With land battles as precedent, the introduction of staged naval battles was an expected next step.

However, recreating a recent Roman campaign in the Campus Martius—a site at least loosely appropriate for such reenactments—is quite different from restaging a Greek naval battle inland, in a man-made arena. Moreover, other sources reveal that aquatic spectacles in Rome extended beyond naval warfare, incorporating adaptations of pantomime to present mythological narratives with marine themes. (Launching into History: Aquatic Displays in the Early Empire, by K. M. Coleman)

What Were Naumachiae and How Were They Organized?

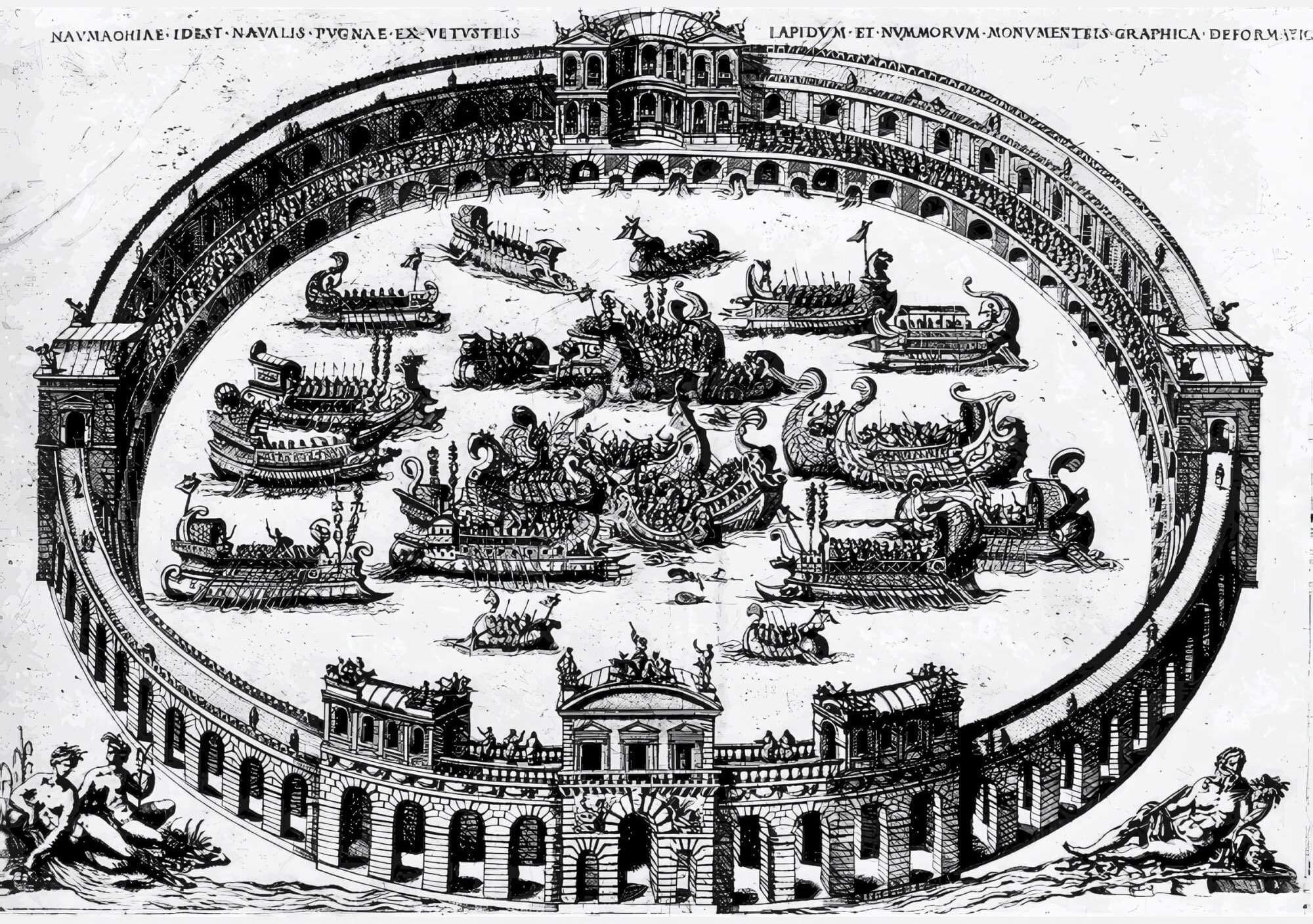

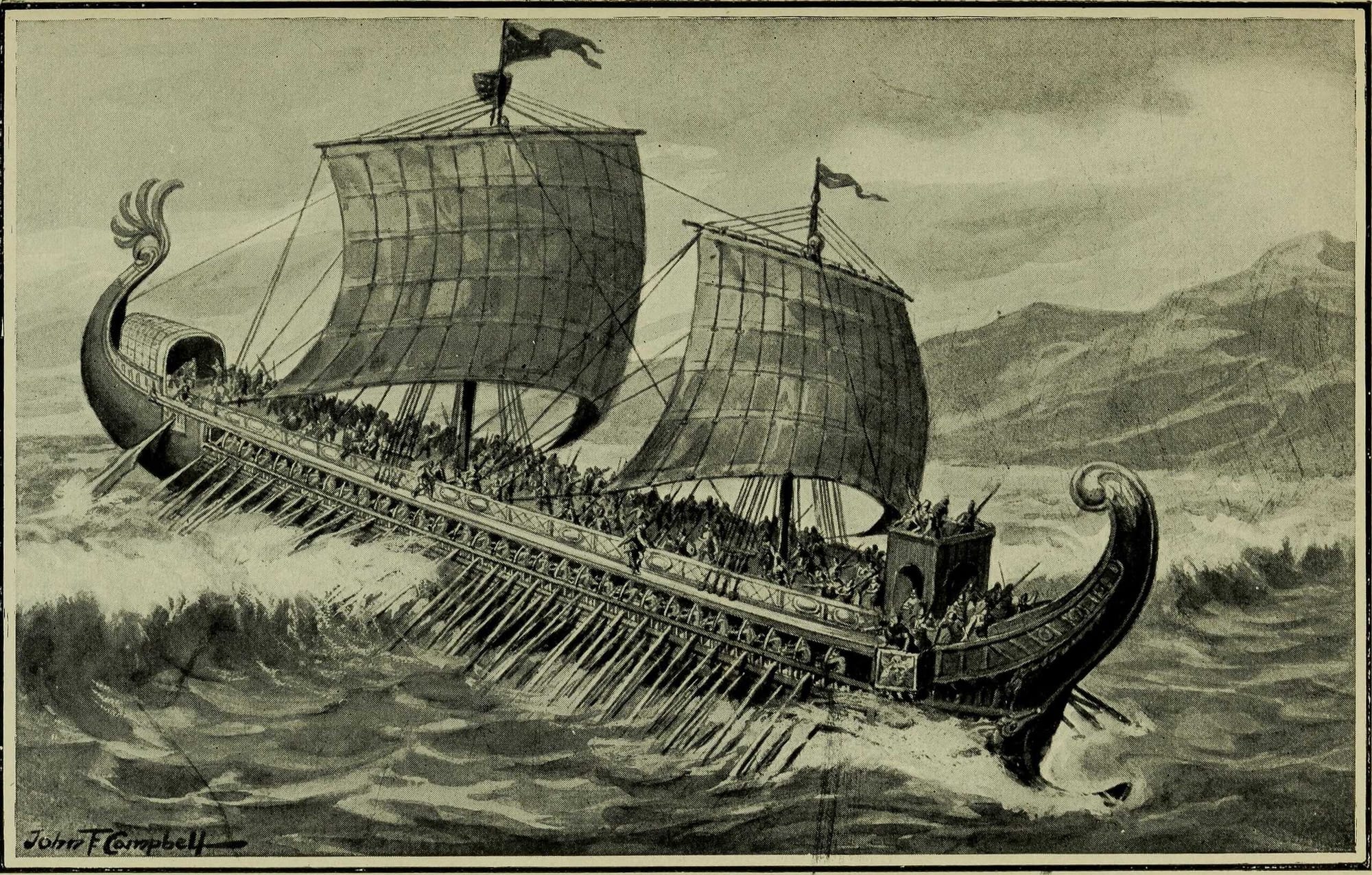

Naumachiae were elaborate naval reenactments staged in man-made basins before vast crowds. These uniquely Roman spectacles featured authentic military ships manned by oarsmen and armed fighters, often dramatizing scenes from classical Greek history.

The sophistication of these displays demanded extensive resources, specialized equipment, and venues capable of supporting such a scale.

La naumaquia painting, by Ulpiano Checa. Credits: Poniol60, Public domain

Historical accounts highlight their rarity and complexity, noting that only emperors could sponsor these events, typically as part of games for special occasions. Naumachiae appear in records from 46 B.C., when Julius Caesar introduced the first for his triumph, and are documented only until around A.D. 89, with no verified reports of similar battles in Rome after that date.

Sources give us only limited insight into the true nature of naumachiae. The most fundamental questions—such as whether these events were accurate recreations of historical battles—remain open to debate. Were the combat tactics reflective of genuine naval strategies, with outcomes dependent on the skill of the participants, or were they carefully orchestrated displays meant to end as history recorded, or simply imaginative spectacles with little attention to realism?

Some scholars even propose that the naumachiae may have been purely theatrical, akin to Renaissance plays, potentially without any real water, merely simulating ships in combat. Answering these questions is central to understanding whether naumachiae were intended as sporting contests or as elaborate performances.

This ambiguity is compounded by the Roman cultural perspective, which didn't clearly distinguish between sport and entertainment; indeed, the Latin term ludus, frequently referring to sporting events, also encompassed staged performances. Thus, defining naumachiae as either sport or theater is challenging, given these blurred lines in Roman entertainment culture.

The Almanac of Naumachiae

The first public naumachia was organized by Julius Caesar in 46 B.C. as part of his triumphal celebrations. For this event, a basin was excavated at Codeta Minor to host a simulated naval conflict between fleets representing Tyre and Egypt. The battle featured a mix of biremes, triremes, and quadriremes, staffed by around 4,000 rowers and 2,000 soldiers, all condemned prisoners of war.

Later, in 40 B.C., Sextus Pompey staged an elaborate event at Rhegium to celebrate his conquest of Sicily, where he included a naval battle with small boats manned by war prisoners, adding a satirical twist on his victory over Salvidienus Rufus, an ally of Augustus.

In 2 B.C., Augustus arranged a re-enactment of the Battle of Salamis, which involved 30 biremes and triremes, as well as smaller vessels, totaling 3,000 soldiers. To accommodate this spectacle, Augustus commissioned the Naumachia Augusti, a dedicated basin supplied by the Aqua Alsietina aqueduct.

Caligula planned a similar structure at the Saepta Julia in 38 A.D., but it was never completed. Claudius, in 52 A.D., staged one of the largest naumachiae recorded, involving two fleets of 50 ships each, with a combined force of 19,000 soldiers, to celebrate the completion of the Fucine Lake canal. Nero held two naumachiae in 57 A.D. and 64 A.D., the first a re-enactment of the Battle of Salamis for the debut of his amphitheater in Campus Martius.

At the inauguration of the Flavian Amphitheatre in 80 A.D., as aforementioned Titus organized spectacular games that included a naumachia in the Naumachia Augusti, simulating a battle between Athenian and Syracusan forces. Another battle re-enacting the conflict between Corcyra and Corinth in 434 B.C. was held in the amphitheater itself.

Domitian followed with two naumachiae, one in the Flavian Amphitheatre and the other near the Tiber during his Dacian triumph in 89 A.D. These events are the last reliably documented imperial naumachiae. Although Heliogabalus later held unspecified navales circenses, they likely resembled regattas rather than combat.

Philip the Arab is recorded as having dug a basin near the Tiber, possibly for a naumachia or as a repair of the Naumachia Augusti, to mark Rome's millennium in 247 A.D., though evidence is unclear. In the fourth century, mock naval displays continued, such as those on the Moselle River, though they likely involved no actual fighting.

The Locale of Naumachiae

In Rome, naval battles took place both in specially designed facilities and multi-use venues. One of the earliest, the basin at Codeta Minor, was commissioned by Julius Caesar and possibly located in either the Transtiberim or Campus Martius areas. The limited information available makes it unclear if this basin was a permanent structure or a temporary setup with grandstands around a large pool. This venue was short-lived; it was filled in under Augustus due to suspicions that it spread disease.

Later, Augustus constructed the Naumachia Augusti, a large basin fed by the Aqua Alsietina, a purpose-built aqueduct, located in the Transtiberim. This basin, surrounded by a grove of trees (or nemus), became famous for hosting elaborate naval spectacles and continued to serve as a venue even as others were built. Known as the "vetus naumachia" (the old naumachia) in later years, it was one of the city’s primary locations for these displays. Additionally, Domitian is recorded to have excavated another basin near the Tiber for similar purposes.

Among the multi-purpose venues hosting aquatic displays was a basin built by Agrippa in the Campus Martius, originally intended as a swimming pool for his baths. This site, likely too small for full-scale naumachiae, hosted banquets under Nero. Augustus later staged aquatic shows with animals in the Circus Flaminius as part of his naumachia inauguration festivities.

Nero also utilized a wooden amphitheater, where two naumachiae marked its opening, and the Flavian Amphitheatre (Colosseum) eventually followed suit.

The Colosseum at night. Credits: Andrea Bova, Pexels

There were also natural settings used for naumachiae: Sextus Pompey organized one in the sea near Rhegium in 40 B.C., and Claudius staged a grand event on Fucine Lake in 52 A.D. Records from the fourth-century Notitia and Curiosus Urbis Romae indicate that Region XIV of Rome had five naumachiae. Even if this count includes basins capable of only limited water displays, it suggests that Rome had numerous aquatic venues.

However, only the Flavian Amphitheatre, where the last recorded naumachiae took place, remains intact, offering vital insights into their layout and allowing historians to assess the reliability of ancient accounts. (Sport or Showbiz? The Naumachiae in the Flavian Amphitheatre, by Francesca Carello)

How did Romans Flood the Colosseum?

Martin Crapper, lecturer at Edinburgh University’s school of engineering and electronics in his paper, “How Roman engineers could have flooded the Colosseum”, applying modern engineering methods, suggests that despite gaps in the archaeological record, it was feasible to fill the central 80-meter-long (±260 feet) arena within 2 to 5 hours, with an equally rapid drainage time.

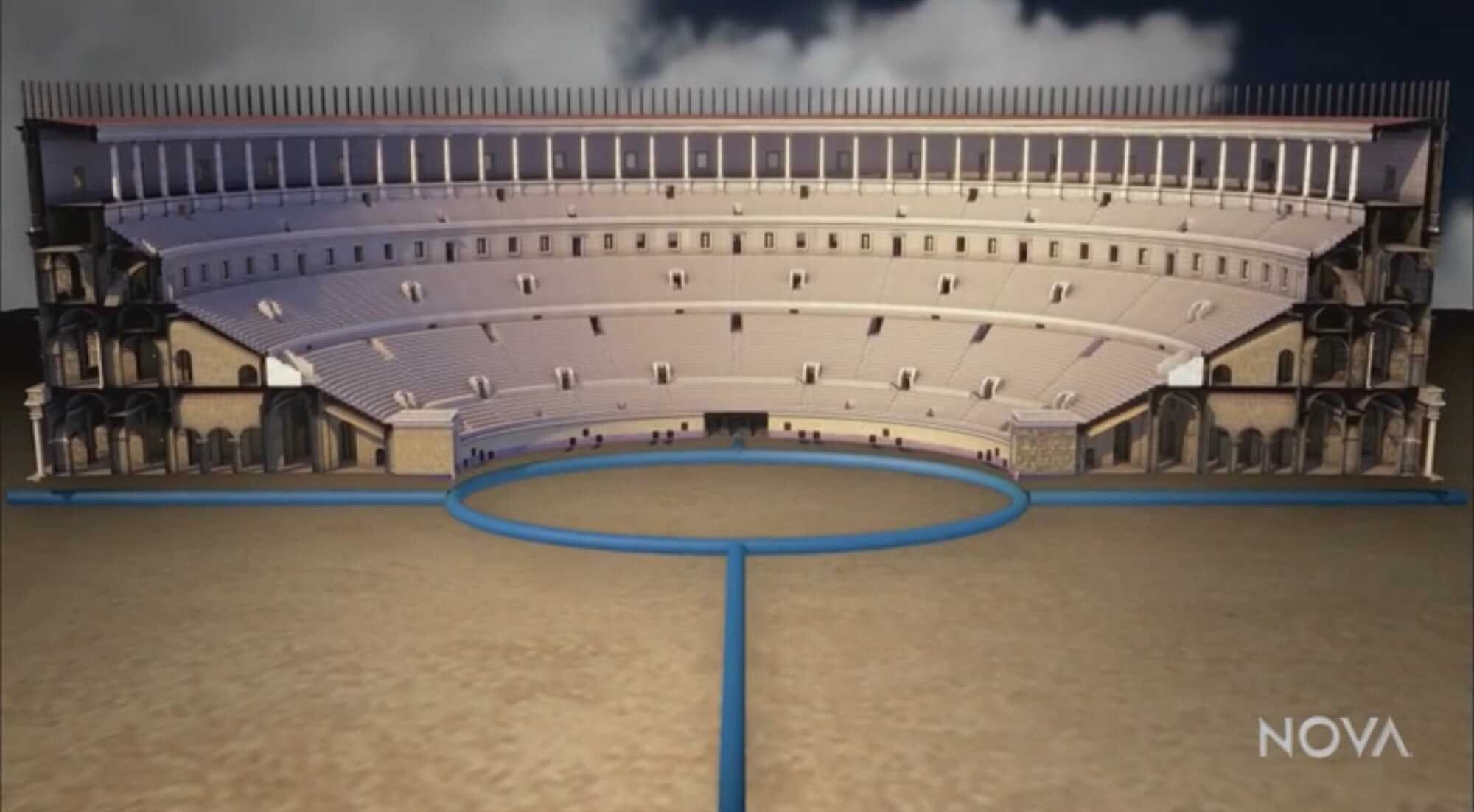

He says that the current view of the Colosseum reveals substantial stone structures in the underground chamber, or "hypogeum," beneath the arena floor. These substructures are believed to have been added after the amphitheater’s initial construction, with the original hypogeum likely being an open space.

The arena floor was initially supported by a wooden framework that could be removed and reinstalled, as evidenced by post holes found in the hypogeum. A replica of this timber structure has been reconstructed at the Colosseum’s east end. Parts of the hypogeum walls are lined with mortar, which, according to a scientific analysis , was of sufficient quality to provide basic waterproofing.

This configuration suggests that for early staged sea battles, or naumachiae, the timber arena floor could be removed to flood the chamber below. The hypogeum itself is about 6 meters (±20 feet) deep, but four radial service passages located roughly 1.5 meters (±5 feet) above the base would have limited water depth to around the same height, suitable for re-enactments.

Although this depth would have left the water surface partially out of view for some seats, it would still allow for an immersive, large-scale naval display. Given the arena's elliptical shape (approximately 80 by 45 meters — 262 by 147 feet), filling it to a depth of 1.5 meters (±5 feet) would require around 17,000 cubic meters (±600,000 cubic feet) of water.

The most plausible water source for the Colosseum was likely Nero’s branch of the Aqua Claudia aqueduct, originally constructed to supply Nero’s large fountains on Caelian Hill. In the 19th century, a cistern was found on Caelian Hill, but no details on its dimensions remain, and there’s no visible trace of it today. However, the cistern would have been positioned around 50 meters (±165 feet) above sea level, approximately 25 meters (±82 feet) higher than the arena floor, and about 300 meters (±1,000 feet) away from the Colosseum.

Whether for naumachiae or general use, the Colosseum required a steady water supply to maintain numerous fountains, especially to provide relief for audiences seated in the sun for extended periods. This system, likely used lead pipes, common in Roman plumbing, with diameters up to around 300 mm (±11.8 inches). It’s reasonable to assume these pipes delivered water from the aqueduct via the cistern on Caelian Hill.

Martin Crapper’s survey found the Aqua Claudia’s typical channel dimensions to be approximately 1.46 meters (4.79 feet) high and 0.84 meters (2.76 feet) wide, with an average gradient of 0.004 over the 8 kilometers from outside the city to the Colosseum. The aqueduct, which likely ran close to full capacity, was built with smooth, well-maintained masonry.

The Aqua Claudia aqueduct, built in ancient Rome, had a steady flow of water directed toward the city. Its water channel was about 1.5 meters (±5 feet) high and just under a meter wide, with a gentle downward slope that allowed water to flow smoothly. Ancient engineers estimated it could deliver around 2 cubic meters of water per second—a flow similar to modern estimates.

If all of this water could be directed into the Colosseum, it would be enough to flood its underground level, or hypogeum, to a depth of about 1.5 meters (±5 feet) in just over two hours. This means the Colosseum’s arena could be filled efficiently to stage sea battle reenactments, known as naumachiae, without extensive delays.

Once the Colosseum was filled for a mock naval battle, it would need to be emptied afterward. The amphitheater achieved drainage through four culverts, each positioned at the primary axes of the elliptical structure, situated just below the hypogeum’s service passages. These culverts, roughly 1 meter (±3 feet) wide by 1.5 meters (±5 feet) high, led to a larger passage encircling the Colosseum that linked with the city’s sewer system. At the eastern section, remnants of a sill suggest that a sluice gate may have been used to control water flow during these events.

Besides draining after mock sea battles, the Colosseum’s system also handled routine runoff from drinking fountains, rain, and other waste. Wastewater would likely collect in the arena's inner ring and flow down through shafts to the hypogeum’s edges, ultimately reaching one of the drainage channels. The central hypogeum floor, usually covered by the arena above, would generally stay dry.

To estimate the drainage time after a naumachia, a scientific (Matlab) model was used. The model treated the culverts as open channels with unrestricted outflow, assuming symmetry and neglecting friction losses at the culvert entrances or any downstream effects that might slow drainage. Thus, this analysis represents an optimal scenario for maximum drainage speed.

While significant gaps in archaeological evidence prevent a fully detailed analysis, current findings suggest that the Colosseum could be flooded within 2–5 hours for mock sea battles and drained in roughly the same amount of time.

Media Credits: Produced by NOVA. Third party materials provided by bpk, Berlin / Art Resource, NY, Bridgeman Images, Corbis, Getty Images, Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington, D.C.

Setting up the Performance

Alison Futrell, in “The Roman Games: Historical Sources in Translation,” notes that under Augustus, a "standardized show" known as munus legitimum emerged, featuring three main acts: morning animal hunts (venationes), midday executions, and afternoon gladiatorial battles—the day's main attraction.

As time passed and naumachiae (naval battles) found their way into amphitheaters, they became part of these elaborate games, blending with other spectacles staged in the same venue. Although gladiator fights were often considered the highlight, each performance held varying importance across different eras.

Naumachiae have deep roots, originating in Classical Antiquity, but their impact reached beyond Rome. Notable revivals include a re-enactment during the lavish Medici wedding in Baroque Italy and, later, 18th-century England, where naval spectacles were staged in aristocratic garden ponds. While these later adaptations leaned towards theater, Roman naumachiae were distinct for their brutal realism, likely involving unwilling participants. (Theatricality of Naumachiae, by Lucia Steltenpohlová)

The naumachiae were also significant for political reasons, allowing emperors to showcase their wealth, power, and control over nature. These spectacles served as propaganda, reinforcing the might of Rome and the emperor’s ability to entertain and awe the populace.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: