Frontinus: Rome’s Master of Strategy and Water

Sextus Julius Frontinus embodied Rome’s genius for both war and order. From battlefield stratagems to aqueducts, his works reveal the mind of a senator who mastered strategy and sustained the Eternal City.

Few Romans embodied the marriage of war and order as completely as Sextus Julius Frontinus. A soldier, senator, governor, and author, he left behind two works that capture the essence of Rome’s might: the Strategemata, a manual of military ruses drawn from history, and De aquaeductu urbis Romae, the first great treatise on Rome’s water system. His life and writings reveal not only the ingenuity of a commander but also the meticulous care of an administrator charged with sustaining the world’s largest city.

An Aristocrat at the Summit of Roman Politics

In Rome of the late first century A.D. few aristocrats could compete with the preeminence of Sextus Iulius Frontinus. His career spanned consulships in 72/73, the governorship of Britain under Vespasian, command of the Lower German army between 81 and 83/4, and the proconsulship of Asia around 84–85.

Under Nerva, he assumed control of the city’s water supply, and his prominence only grew with the rare distinction of near-consecutive consulships: suffect consul in 98 and ordinarius in 100 under Trajan. Such repeated honors were unheard of outside the imperial family, marking him as a figure of extraordinary influence.

Pliny the Younger reflected this status when he described Frontinus as a princeps vir and spectatissimus in the eyes of the state.

“For Frontinus was a man of the highest distinction, and, as our State judged, the most eminent of citizens.”

Epistulae, 4.8.3

“…Frontinus, who was considered by our State the most conspicuous and distinguished man of his time.”

Epistulae, 5.1.5

Tacitus too judged him to be “vir magnus quantum licebat”, as great a man as the times would allow.

“He was a great man so far as it was possible in those times.”

Tacitus, Agricola 17.2

His military reputation matched his political one. Aelian recalled conversations with him:

“…after talking at Formiae with the distinguished consular Frontinus, a man of great reputation by virtue of his experience in war, I was inspired to pursue the study of tactics.”

Aelian, Tactica

Later, Vegetius singled him out from earlier military writers, noting that his industria had won the approval of Trajan.

“Frontinus also wrote on military science; his industry in this respect was approved by the deified Trajan.”

Vegetius, Epitoma Rei Militaris 2.3.7

Such testimonies reveal a man whose writings, positions, and achievements combined to make him both an authority and an exemplar.

The Strategemata: Pragmatism or Politics?

Frontinus’ Strategemata, written during Domitian’s reign, set down his military experience in the form of practical examples. These anecdotes were meant to instruct, but they also helped shape his public image. Some see the work as cautious and deliberately apolitical, while others suggest that its praise of Domitian’s generalship might have carried a subtle undercurrent of criticism, expressed more in what Frontinus left unsaid than in what he wrote.

Yet the evidence suggests otherwise. Domitian appears more often than any other emperor in the Strategemata, and his portrayal is consistently complimentary. Frontinus even inserts himself into one example, serving under Domitian’s command, thereby linking his own authority with the emperor’s. Rather than subversion, this presents a deliberate alignment with the regime.

Between Domitian and Trajan

The question then arises: what became of this alignment after Domitian’s death in 96? Unlike Pliny or Martial, Frontinus did not join the chorus of denunciation. His De Aquaeductu, written under Nerva and Trajan, shows no attempt to distance himself from his earlier support.

Pliny hints that Frontinus was not inclined to agonize about the past, but this was not mere temperament—it reflected security. Frontinus was too powerful a figure to need to excuse his conduct under Domitian. The Strategemata, far from being a “simply antiquarian” exercise, was part of Frontinus’ self-fashioning: a demonstration of his experience, his alignment with the ruling power, and his authority in military science.

It secured his standing under Domitian and did not hinder his influence under Trajan. Through both office and authorship, Frontinus emerged as a statesman whose mastery of strategy extended beyond the battlefield into the political arena.

Britain’s Future Governor in Training

The Second Adiutrix and the Thirteenth Gemina had marched north from Italy by the west-Alpine passes, crossing directly through the Lingones’ homeland on their route to Tréves. Their passage explains the final submission of the tribe recorded by Frontinus. The revolt ended without bloodshed, enabling Cerialis to turn his attention to Civilis and the lower Rhine.

Of these two legions, the Thirteenth was an old Pannonian unit that had distinguished itself in the fighting against Vitellius. Its commander, Vedius Aquila, was still alive and apparently secure in his post, since Tacitus would surely have mentioned his removal or death.

With so many new commands already to be filled after the civil wars, Rome was unlikely to replace him. That left II Adiutrix, the brand-new legion, in need of strong leadership. Placing Frontinus at its head would have been both practical and politically sound.

The legion did not remain long in Germany. Once Civilis was crushed, Cerialis was dispatched to govern Britain. He took II Adiutrix with him, replacing the Fourteenth Legion, which was reassigned to Upper Germany. If Frontinus had been its commander during the submission of the Lingones, he would still have held that command through part of Cerialis’ subsequent northern operations.

In this way, he acquired direct experience of British affairs before becoming governor himself in 74. This conclusion is more than a small biographical note. The Flavian regime faced the challenge of stabilizing Britain while simultaneously pushing Rome’s frontier further north.

The province was unsettled, and decisive action was expected. Cerialis, Agricola, and, as the evidence suggests, Frontinus all came to their governorships with prior knowledge of the province, enabling them to act with confidence. Frontinus’ brief remark in the Strategemata, long puzzling to scholars, therefore has greater weight.

It shows that he too had been tested in the field before taking command of Britain, placing him on the same level as his more famous contemporaries. He did not arrive as an administrator alone, but as a soldier who had already dealt with the challenges of the land he would govern.

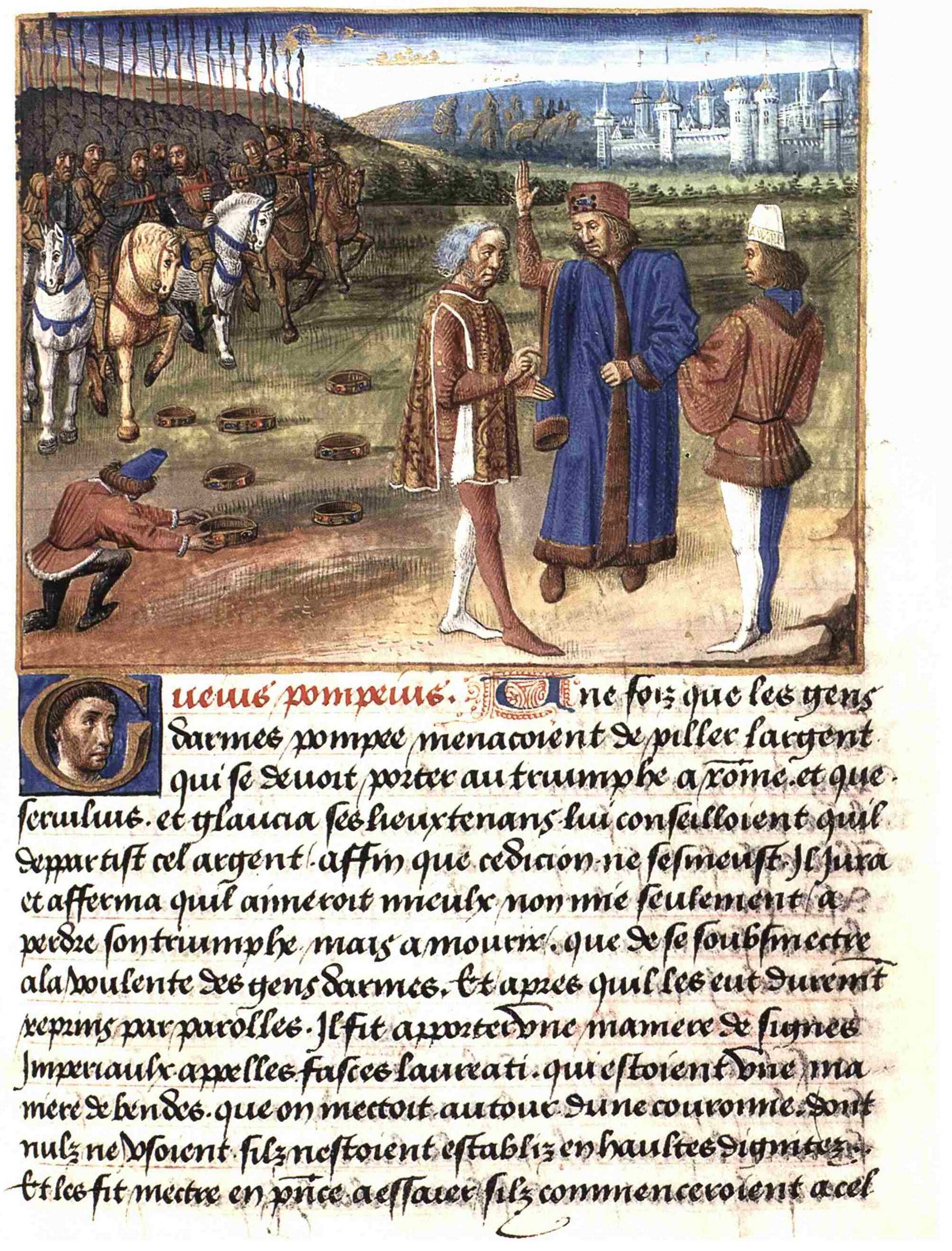

A Tradition of Cunning: Frontinus and the Roman Art of Stratagems

The genre of stratagem collections had deep roots in both Greece and Rome. In Greece, the recording of clever ruses in war grew naturally out of the narratives of Homer and Herodotus, where cunning was celebrated alongside bravery.

By the fourth century BCE it had developed into a distinct form of military writing, designed to instruct by example. Such material could be gathered for rhetorical training or incorporated into broader tactical manuals, like the Strategika of Aeneas Tacticus or Pyrrhus’ Tactica.

Rome inherited and adapted these traditions. Funeral laudations of great men included martial exempla, reinforcing the prestige of ancestral cunning, while Valerius Maximus in the early empire compiled the Factorum ac dictorum memorabilium libri IX, which devoted a chapter to stratagems.

Yet it was Frontinus who produced the earliest surviving independent collection of stratagems. His Strategemata, though conceived as a supplement to a now-lost treatise on the scientia rei militaris, became the most important Roman example of the genre.

Frontinus’ work belongs to what can be called a golden age for stratagem collections, beginning with his own and ending with that of Polyaenus.

Closeup of the Frontinus Gate in Hiérapolis. Credits: Emmanuel PARENT, CC BY-NC 2.0

After Polyaenus, the genre largely disappeared until the Byzantine period. Frontinus assembled 583 examples of cunning deeds of commanders (sollertia ducum facta) to inspire future generals to attempt similar feats. He stressed the practical utility of the collection, explaining in the preface that it had been carefully arranged for quick consultation.

The first three books cover stratagems before battle, during and after battle, and in siege warfare, while the fourth gathers examples under the broader heading of strategika. Each book opens with an index of tactical categories, and under each category the exempla are grouped by the names of the generals or peoples who employed them.

This pragmatic design becomes clearer when compared with Polyaenus’ Strategika, written during the Parthian War of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. Polyaenus’ work was more expansive and literary, arranging its 900 examples thematically, ethnographically, and geographically, and even dedicating sections to barbarians or to his Macedonian ancestors.

His aim seems partly to have been complementing rather than competing with Frontinus, but also to indulge a contemporary taste for biography and cultural identity. The result was more “readable” as literature, but less directly suited for military reference than the sharply practical layout of Frontinus’ Strategemata.

The insistence on practicality was not mere pretense. Roman culture valued learning by example, whether through elders, speeches, or books. Frontinus himself, in the preface to his De Aquaeductu, says that he wrote that work to train himself for an unfamiliar office, preferring to learn from theory rather than from assistants. The Strategemata reflects the same spirit: it was a literary product rooted in his own practice, intended to prepare future generals.

To dismiss his stated motivation as just a literary convention would be unfair. In a society without formal institutions for teaching strategy, such manuals offered a real means of instruction. Even Cicero, who boasted that Rome’s great commanders learned in the field, admitted that warcraft could be studied from books. His own experience as governor of Cilicia shows him taking tactical advice from a colleague who had drawn it from written manuals.

This background explains how stratagems circulated among commanders and historians alike. Tacitus describes Petilius Cerialis sparing the property of Julius Civilis while ravaging the Batavian countryside and calls it nota arte ducum—a familiar stratagem.

records the same ruse under Dionysius I, noting that many generals had used it. Such overlaps suggest that military treatises played a part, alongside history, in transmitting knowledge of tactics. Frontinus could not control who read his work; its clear organization would have made it valuable not just for soldiers but also for historians, lawyers, and orators seeking vivid examples.

The bulk of the Strategemata looks to the past. Out of 583 examples, 567 come from Greek, Hellenistic, or Republican Roman history. This emphasis reflected both the available source material—especially writers like Valerius Maximus—and a cultural preference for ancient over recent exempla. Roman literary taste gave pride of place to the authority of antiquity. Cicero himself insisted on the superior weight of older examples, and Quintilian echoed the same view.

Tacitus and Pliny the Younger occasionally defended the relevance of recent cases, which suggests that the prevailing opinion leaned toward the authority of the past. This tendency was part of the wider literary culture of the Roman Empire, which often preferred the models of antiquity to contemporary references. (Frontinus and Domitian: the politics of the Strategemata, by S.J.V. Malloch)

Frontinus and the water supply of Rome

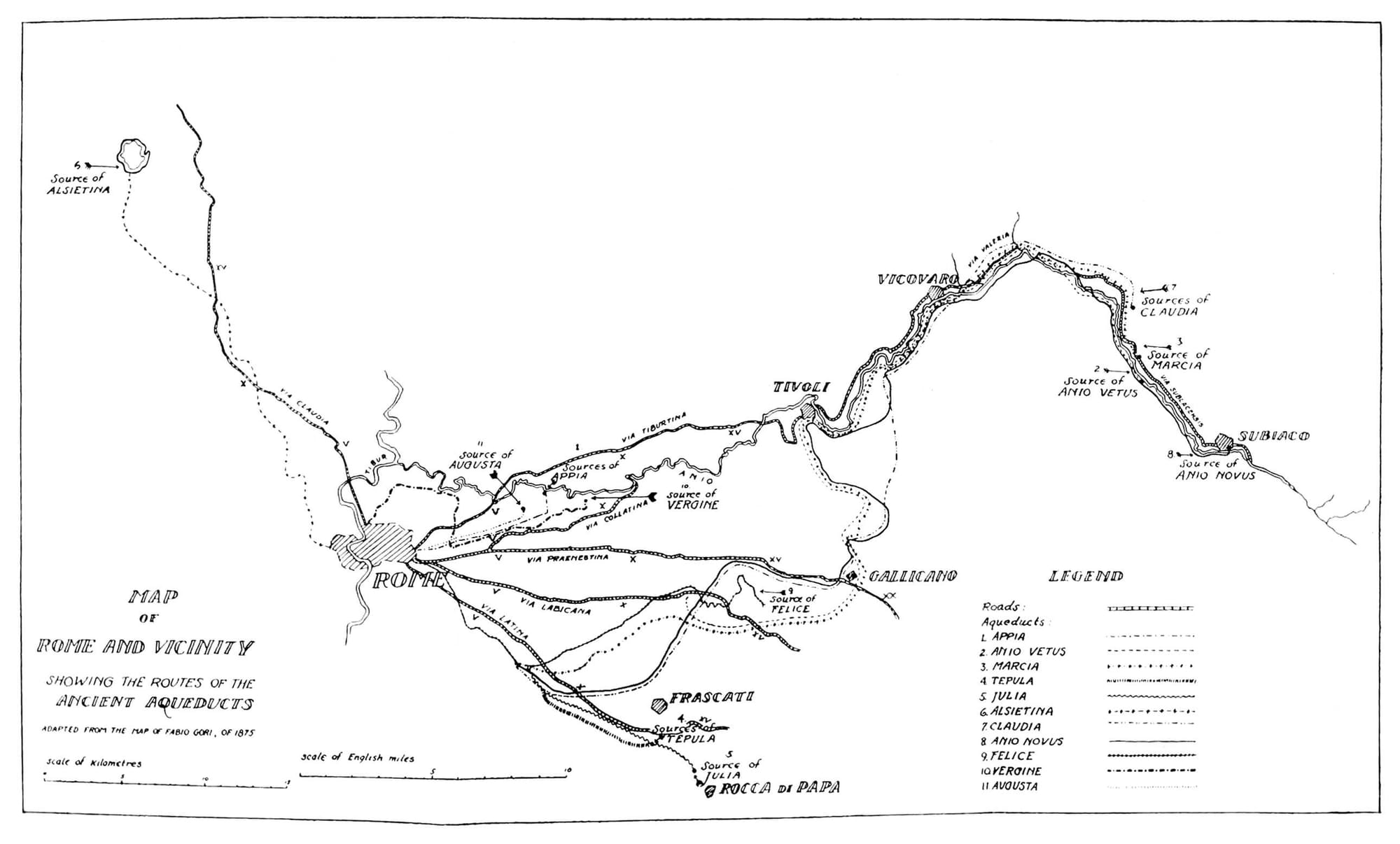

The aqueducts of Rome, admired since antiquity, are understood today above all through the work of Sextus Julius Frontinus. Appointed curator aquarum under Nerva, he left the De aquaeductu urbis Romae, the only surviving ancient treatise on the city’s water supply.

In it, Frontinus described Rome’s network of aqueducts, their capacities, and their distribution within the city. Though archaeology continues to refine our picture, his treatise remains the foundation for any study of how water was managed and consumed in the capital, offering invaluable insight into where, when, and why water was needed in ancient Rome.

Metropolitan Rome, the domina orbis, could boast one of the greatest treasures of her empire: an abundant and ever-flowing public water supply. From Strabo onward, visitors to the Eternal City marveled at the aqueducts, not only for their utility but for their monumental grandeur.

In 97 CE, as already mentioned, Sextus Julius Frontinus was appointed by Emperor Nerva to the office of curator aquarum, charged with overseeing this system. He represented the model of a senior senator working in close partnership with the princeps for the good of the commonwealth. For Frontinus, the aqueducts stood as monuments of Roman greatness, more impressive in their practical service than the pyramids were in their spectacle.

In his De Aquaeductu Urbis Romae, composed after Nerva’s death as Trajan prepared to assume power—a succession in which Frontinus himself seems to have had influence—he outlines his duties, responsibilities, and achievements during about a year in office. The work provides a sketch of the history of Rome’s aqueducts, detailed technical data on sources and delivery, verbatim quotations of legal documents, and reflections from an administrator’s perspective.

Yet it is not an engineering manual, nor a fiscal record, nor a handbook for future curators. Modern readers, often more eager to extract information than to read it as a literary text, have sometimes overvalued or undervalued Frontinus accordingly.

The truth is that we cannot be sure of the purpose he intended. What remains certain is that nothing else quite like De Aquaeductu survives from the ancient world, making it a unique and enigmatic window into the infrastructure and ideals of imperial Rome.

Frontinus’ De Aquaeductu: Records, Reflections, and the Enigma of a Roman Commentarius

In the prologue to his De Aquaeductu, Frontinus describes the work as a commentarius, a collection first intended for his own instruction. Yet its contents show a wider purpose.

He offers data on each aqueduct—their builders, dates, sources, lengths, and delivery points—along with information on the distribution of water by pipes, supply quantities, and the categories of use, whether public, private, or imperial. He also records legal provisions governing water rights, maintenance, and penalties for abuse.

But Frontinus does more than compile lists. Throughout the booklet he adds commentary, criticism, and plans for reform, including a careful review of official water figures and proposals for improvement. In doing so, he created a hybrid record: both archive and analysis.

Though styled as a modest aid for personal reference, De Aquaeductu clearly addressed a broader audience, setting out the duties and achievements of Rome’s curator aquarum. Neither technical manual nor simple administrative guide, the work stands as a unique specimen of Roman literature—and the only surviving text of its kind from the ancient world.

From Personal Notes to Public Report

Although Frontinus described his De Aquaeductu as a commentarius for his own reference, the text goes far beyond private notes. It presents findings, criticisms, and reforms in a literary form clearly intended for an audience larger than a single successor. That audience was the Senate and, importantly, the new emperor. The work reflects not only the duties of a diligent administrator but also the ideals and self-presentation of a senior senator.

Some read it as an administrative report, others as political propaganda, a senatorial manifesto, or even as a pamphlet meant to announce the restoration of discipline in the water supply system. Whatever its precise purpose, De Aquaeductu stands as both a record of Rome’s aqueducts and a testament to Frontinus’ authority, character, and political role.

Duty, Reform, and the Grandeur of Rome’s Waters

From his opening words—res ab imperatore delegata, mihi ab Nerva Augusto (“A task entrusted by the emperor, to me by Nerva Augustus.” )—to his closing lines, where he presents himself as the intercessor for those seeking the indulgentia principis,( the indulgence (or leniency/favor) of the emperor) Frontinus’ De Aquaeductu reveals the image of a conscientious public servant.

For him, effective administration required energetic and personal involvement. Only direct, first-hand knowledge of the system under his care could free the curator from reliance on subordinates. The text reflects this conviction: his reforms, aimed at stamping out fraud among lower officials, stand in sharp contrast to the negligence of his predecessors.

Another theme runs alongside this: the curator’s duty to fulfill the expectations of the emperor who appointed him. Responsibility for Rome’s water supply rested on both princeps and curator, and only close cooperation between them could ensure success. This partnership had unequal parts, but the aqueducts—among the brightest jewels in Rome’s imperial crown—demanded such collaboration.

Frontinus saw this relationship not as an ideal but as inherent in the office itself, established by Augustus in 11 BCE to perpetuate the services once provided by Marcus Agrippa. Beginning with his lavish aedileship in 33 BCE, Agrippa had personally financed new aqueducts and employed slaves for their upkeep.

After his death, Augustus inherited these resources and assumed the larger burden himself, while entrusting routine administration to a senatorial curator. The prestige of the office was high, honoring Agrippa’s legacy, and Augustus’ choice of Messala Corvinus as first curator underscored its dignity.

By Frontinus’ time, more than a century later, the system had changed. Claudius had doubled the water supply by building two new aqueducts and funding them at his own expense. He also created a parallel administrative branch staffed by imperial slaves and freedmen, which may have overshadowed the senatorial curator.

Whatever the circumstances, Frontinus portrays the administration he inherited as disorganized and ineffective. His diligentia restored order. He disciplined the workforce, clarified duties within the service, and redefined the curatorial office itself.

Guided by the legislative acts that had established the post, he sought not to invent a new role but to restore its senatorial dignity. To praise Rome’s aqueducts was to praise Rome itself. In recounting their history, he honored their auctores, the great figures who had built them, and positioned himself in their line.

Antiquarian touches appear—references to Appius Claudius’ intrigues, Marcius Rex’s triumph, legal extracts from the archives, even trivia from Ateius Capito—but his strongest words are reserved for the structures themselves. These aqueducts, he insisted, surpassed the most wondrous monuments of earlier civilizations, for they were both useful and grand.

Their upkeep was essential, cum magnitudinis Romani imperii vel praecipuum sit indicium—a foremost sign of Rome’s imperial greatness. They provided for the public needs of the capital, safeguarded the health of its citizens, and gave to the regina et domina orbis —queen and mistress of the world, Rome— the wholesome atmosphere befitting her supremacy. ("Frontinus: De aquaeductu urbis Romae". Cambridge classical texts and commentaries. Editors: J. Diggle, N. Hopkinson, J.G.F Powell, M.D. Reeve, D.N. Sedley, R.J. Tarrant. Edited with introduction and commentary by R. H. Rodgers, Professor of Classics, The University of Vermont)

Frontinus stands at Rome’s hinge between war and order. Under Domitian he codified the ruses that steady armies; under Nerva and Trajan he restored the discipline that sustains a city. Read together, his books reveal one ethic—clarity, duty, and a loyalty that kept Rome’s power moving.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: