A Roman’s Manual for Survival

What if one man, standing at the twilight of Rome, believed that the fate of peace depended on the art of war? His words, written more than 1,500 years ago, became the backbone of medieval strategy and echoed in the training grounds of emperors and knights alike.

Some voices rise in times of crisis only to fade with the centuries; others endure, whispering lessons long after empires have fallen. Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus was such a voice — a Roman thinker who wrote when discipline was failing and power was slipping away. His ideas bridged the battlefield and the book, the stable and the Senate, shaping the way generations would understand not just how to fight, but how to preserve the very idea of civilization.

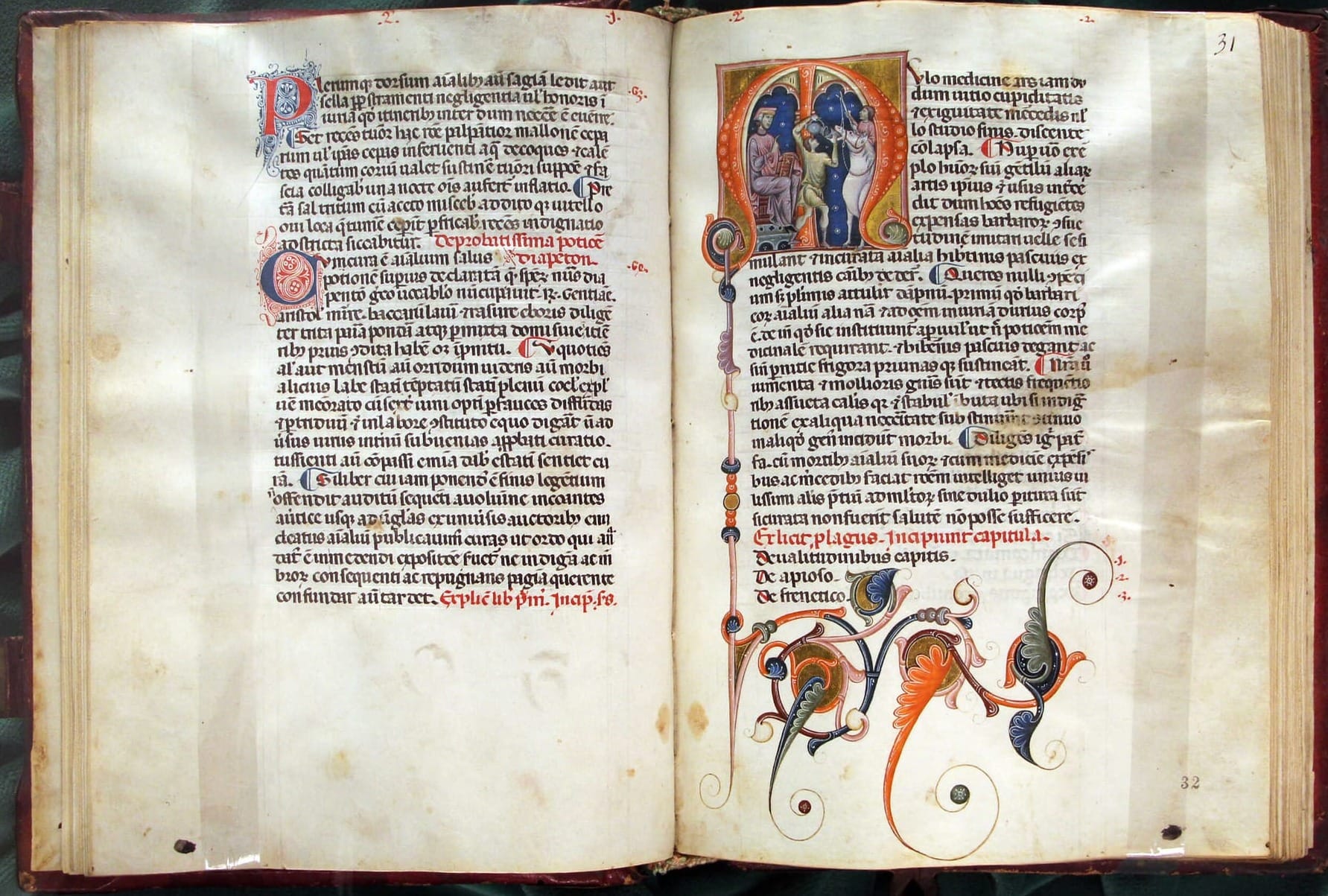

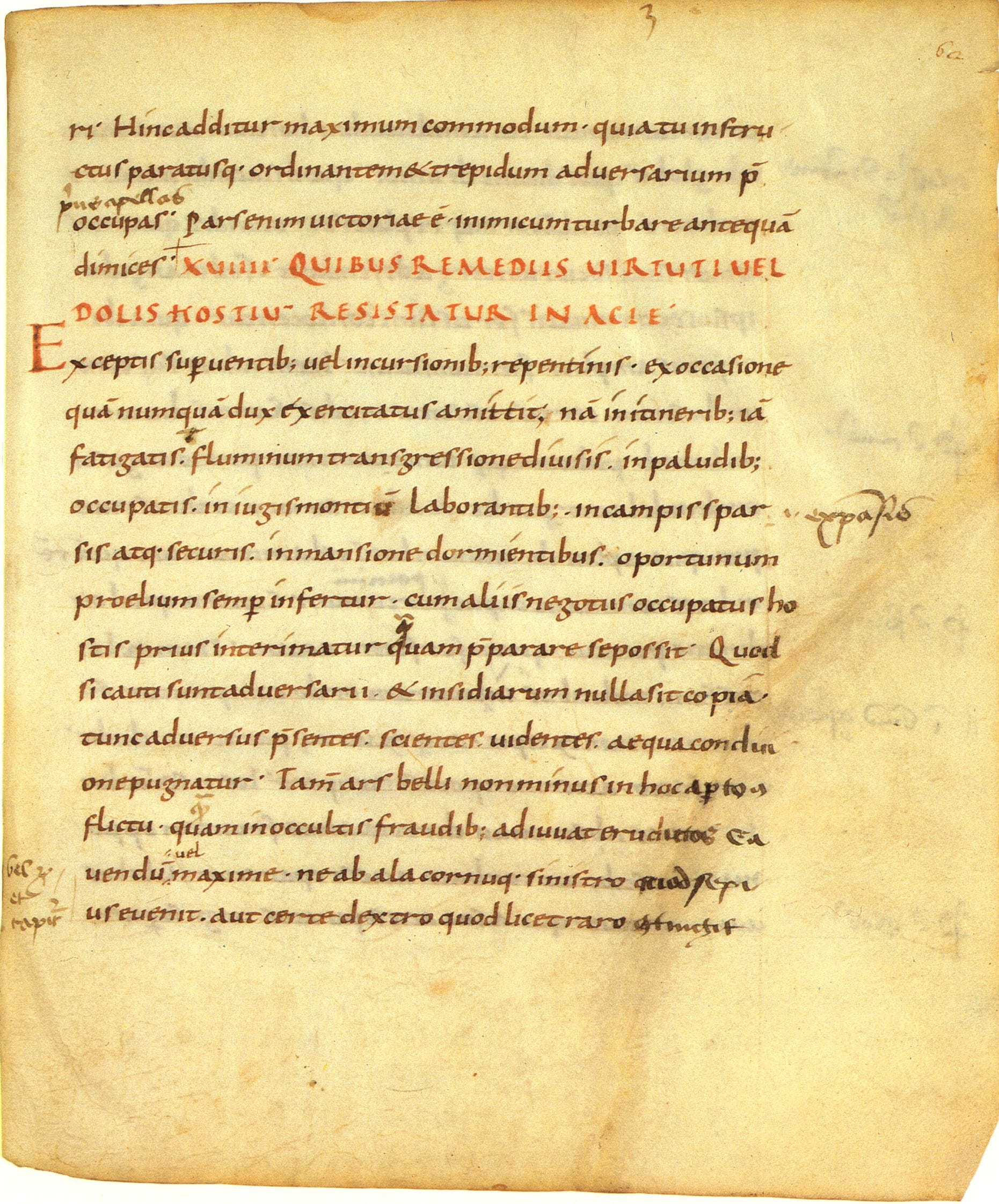

Vegetius composed his Epitoma rei militaris sometime between 383 and 450 CE. The work survives today in no fewer than 220 manuscripts intended as complete copies, including around a dozen produced in the ninth century. The earliest printed editions, however, were based on inferior textual witnesses, and subsequent publishers largely relied on what is arguably the poorest version of all—the Roman edition of 1487.

By the eighteenth century, the situation had not improved: the oldest and most reliable manuscripts were scattered or inaccessible, preventing any of them from gaining the prominence they deserved in shaping the text’s modern transmission.

The Forgotten Face of Vegetius: Rome’s Master of Horses and the Roads that Held the Empire Together

Vegetius, known from manuscript notes as a vir illustris and comes,

It signified someone of great distinction — typically a senior imperial official, governor, or high court dignitary. By the 4th–5th centuries CE, this title was a marker of elite service to the state, not just noble birth.

Comes (plural comites) originally meant “companion” — as in comes Augusti, a “companion of the emperor.” By Vegetius’s time, it had become a formal rank used for imperial counselors, generals, and administrators — for instance, comes sacrarum largitionum (Count of the Sacred Largesses) or comes rei militaris (Count of Military Affairs). In short, it meant he was part of the emperor’s trusted inner circle or held a commanding role in the imperial bureaucracy.

So when Vegetius’s manuscripts describe him as Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus vir illustris comes, they’re essentially identifying him as a high-ranking imperial official — an “Illustrious Count” — of noble or quasi-ministerial standing. That’s why scholars believe he wrote the Epitoma Rei Militaris in an official capacity, possibly as a defense or reform proposal for the army, rather than as a private intellectual exercise.

appears to have added the honorific Flavius to his name once his position in the higher ranks of the imperial administration — whether civil or military — allowed it.

The use of Flavius alongside his Epitoma Rei Militaris but not his Mulomedicina suggests that the former was composed under official authority, while the latter was written privately.

From Vegetius’s own words we learn that the first book of the Epitoma was offered voluntarily to an unnamed emperor; its positive reception led him to prepare the remaining three. This sequence indicates that the work may have begun as a smaller treatise, later expanded and adorned with dedications and rhetorical polish suitable for presentation.

Vegetius reveals himself as a man deeply acquainted with the practical machinery of empire — taxation, recruitment, corruption, and the law. He possessed wide learning in geography, anatomy, history, and mathematics, and he spoke from firsthand familiarity when describing the Hunnish horse or the ailments of mules and oxen. His knowledge of horses was not literary but lived; he was a man who had traveled widely, cared for his mounts, and remembered the traits of the breeds he encountered.

This dimension of his character — the horseman, the observer of animal endurance — has been largely overlooked, eclipsed by the infantry focus of the Epitoma Rei Militaris. Yet the key to understanding Vegetius lies in his Mulomedicina, where his identity emerges more vividly than in any military manual.

The Mulomedicina shows that Vegetius was intimately familiar with the hardships and logistics of the cursus publicus — Rome’s vast network of military and state transport. His descriptions speak of

“inflammation of the feet resulting from wear and tear of the road,”

of

“harmful and excessive galloping,”

and of horses trained for

“smooth riding.”

He writes of wounds

“caused by carelessness of the attendant,”

and of animals

“forced to gallop beyond the limits of their strength,”

suffering from

“broken bones struck by wheels and axles”

or

“abnormally large loads.”

He notes the benefit of

“clean stables with dry plank floors”

and the importance of tending to

“worn hooves and hocks after a journey.”

Vegetius understood these conditions from direct experience. His comment that horses, mules, and donkeys perform their duties

“with their backs alone under saddles or pack saddles”

shows close familiarity with the daily grind of transport animals. He distinguished between the cursus publicus — which he called the

“more mundane services” —

and the nobler functions of horses used for war, racing, or sport. He spoke of

“back damage done by riders,”

“falls caused by fatigue from long journeys or winding roads,”

and of diseases brought on by

“being driven by the lash in rain, snow, hail, and cold.”

He even observed the effects of

“denying horses the chance to urinate because of long hours of galloping.”

His attention to detail, including the use of “old axle-grease” in remedies, contrasts with other Roman veterinary authors such as Pelagonius or Columella, who favored bitumen or pitch.

This practical vocabulary identifies Vegetius as a man who knew both branches of the imperial courier system — the fast cursus velox (the “fast post” branch of the cursus publicus, the imperial courier and transport system that carried official communications and goods across the Roman Empire) and the slower cursus clabularis (the “wagon course” — the slow branch of the cursus publicus, the Roman Empire’s state-run transportation and postal system.

The word clabularis comes from clabula, meaning a four-wheeled cart or wagon used for carrying heavy loads.).

He understood the brutal attrition of the veredi and muli, the saddle and pack animals used by dispatch riders, and he knew the heavy wagons (currus) that carried military and state supplies. In Book IV of the Mulomedicina, devoted entirely to draft animals, he advises,

“When they return covered with mud from the road, take special care not to tire them by too much running or long journeys, nor distress them with loads too heavy.”

Oxen, he warns,

“suited for labor rather than speed, lose their bowels or suffer fevers if forced to actions to which they are unaccustomed.”

Such passages reveal his awareness of the abuse of animals requisitioned by the army or state for transport — a problem deeply familiar to someone involved in supervising the cursus publicus.

Vegetius refers to animals,

“exhausted by carrying their load,”

made ill

“from being drenched or chilled by rain.”

Agricultural references are minimal — just two brief mentions in Book IV — underscoring that his focus was transport, not farming. His knowledge of the cursus publicus also extended to its personnel: muliones (muleteers), carpentarii (wagon-makers), hippocomi (horse-handlers), vehicularii (teamsters), and custodes (guards).

In his Epitoma, he lists carpentarii -coachmen and fabri ferrarii -blacksmiths among the trades useful for recruitment and mentions calones-military servants and galearii-military slaves who fought within the baggage train.

He was also well acquainted with the mansiones and mutationes — the rest stations and changing posts that formed the backbone of the Roman road system. He speaks of stables, byres, and even baths, and records a singular image: a horse being led into the caldarium of the baths to induce therapeutic sweating. Such a scene could not have occurred in an urban bathhouse, but rather at a rural mansio, where travel, rest, and care converged.

These details dispel the long-standing notion that the Mulomedicina was written for the idle amusement of aristocratic readers. Vegetius himself protested this misconception:

“Foolish popular opinion gives rise to the belief that every person of high rank should be ashamed to have knowledge of the art of healing draft animals.”

He wrote instead for those who worked — the paterfamilias and the mulomedicus, the men responsible for the Empire’s beasts of burden. As he wrote,

“But in case a longer book might bring more confusion than instruction, I think I should make an end, while urging you again and again to cure the earliest stages of disease with care.”

His aim was to equip those who labored, not those who dined.

The Mulomedicina was thus a practical manual for the empire’s working class — stablehands, drivers, and overseers who kept the Roman roads alive. Vegetius’s recipes avoid costly ingredients, targeting the thrifty and the practical, those for whom

“the unimpaired health of draft animals entails profit”

and who were

“appointed to oversee their care.”

His prose reflects not a detached scholar but a man of the road, steeped in the rhythm of travel, mindful of animals and men alike. Through him, we glimpse the humbler arteries of Roman civilization: the mud, the wheels, the hooves — and the intellect that bound them all into service. ("Who was Vegetius?" by S. H.Rosenbaum)

The Last Roman “Art of War”

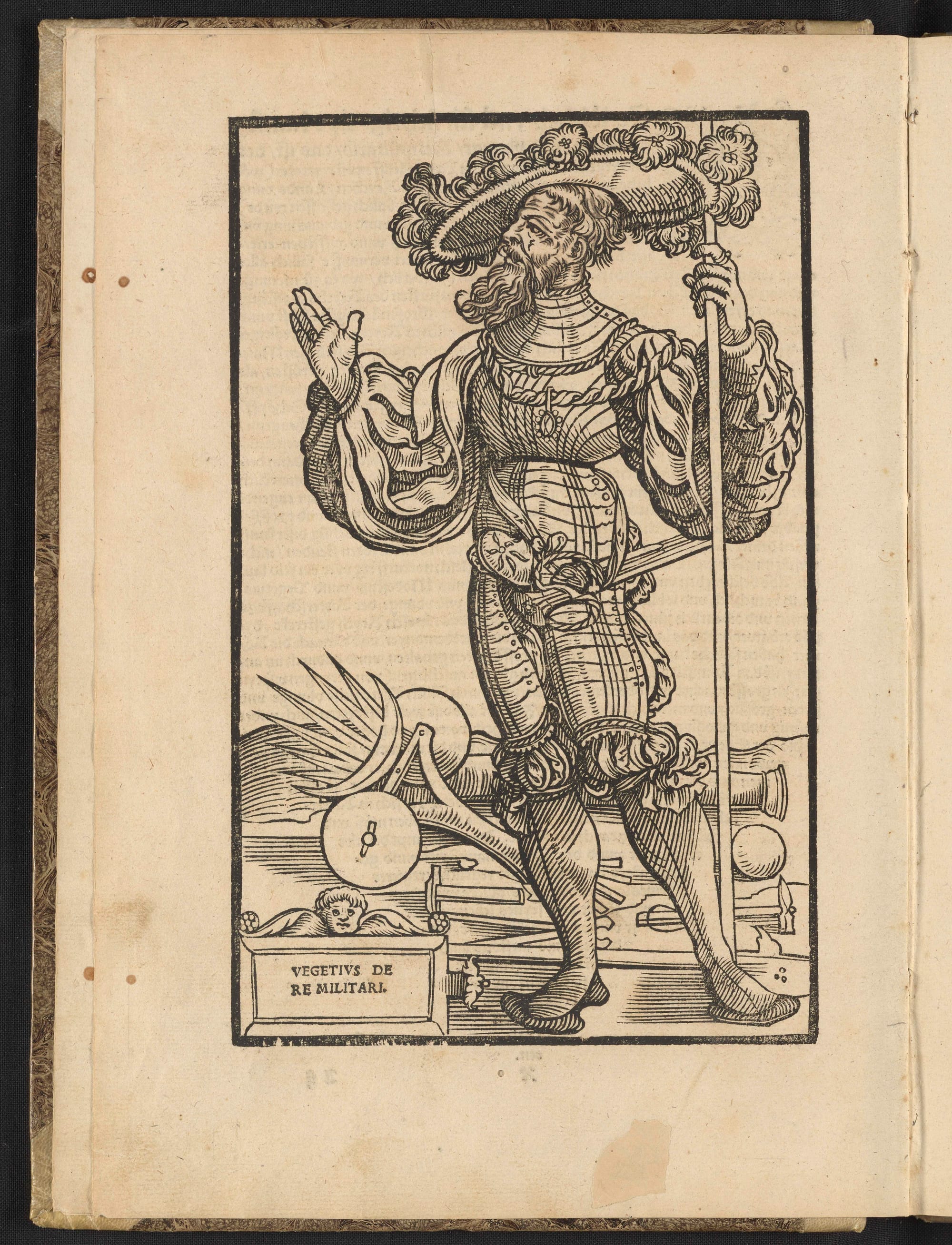

Before Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus set down his Epitoma rei militaris, earlier Romans such as Cato, Celsus, Frontinus, and Paternus had each written treatises on warfare. Yet by the late fourth or early fifth century, Vegetius’ manual stood alone as the only surviving Latin “art of war.”

Though often dismissed as a simple compilation of older military authors, the Epitoma is in fact a work of vision and reform — a coherent program addressed to the emperor, urging the restoration of Rome’s fading military strength.

Vegetius’ message is unambiguous: Rome must return to quality over quantity, to discipline over numbers, and to training over natural talent. His historical view links the empire’s former greatness to its institutions — the moral and structural foundations that once ensured victory. In this, he joins a long Roman tradition of didactic writing meant not merely to instruct but to serve the state.

The heart of his doctrine appears in his famous regulae bellorum generales (Book III) — “general rules of war” — a concise catalogue of maxims that would echo through medieval and Renaissance strategy. For centuries, these regulae were memorized, copied, and applied, shaping the tactical thought of Europe long after the legions had vanished.

The Epitoma rei militaris thus deserves attention as more than a late antique military manual. It offers a rare window into the Roman army of its age, poised between imperial decline and medieval transformation, and it stands as one of the most enduring works of military instruction in Western history. A modern scholar once aptly called it “the bible of warfare throughout the Middle Ages.”

From the cloisters to the courts of princes, Vegetius was cited not only as a strategist but as a moral guide — his emphasis on prudence, order, and discipline harmonizing with both Christian and civic ideals.

During the Renaissance, Vegetius remained the acknowledged master of military wisdom. Readers valued him for his practicality as much as for his antiquarian prestige. Yet despite his enormous Nachleben — his rich afterlife in European thought — Vegetius has long been neglected outside of specialist circles.

To overlook his technical prose is to miss an essential part of ancient intellectual life, for military handbooks formed a vital branch of didactic literature. They stood beside treatises on agriculture, medicine, and rhetoric, written both for the “armchair general” and for the soldier in the field.

War, to Vegetius as to the Greeks before him, was not a temporary condition but a constant of human existence.

“War,”

wrote Heraclitus,

“is the father of all.”

Plato’s Clinias declared that

“a natural state of undeclared war exists between all cities.”

Vegetius echoed the same conviction, calling war

“the indispensable craft, without which other arts cannot exist.”

His treatise, therefore, belongs not only to the history of military science but to the moral and philosophical imagination of Rome itself.

Modern scholarship has largely concentrated on the sources and dating of the Epitoma. The text must postdate 383 CE, when Gratian’s death (emperor of the Western Roman Empire from 367 to 383) made possible the honorific divus Gratianus, and it cannot be later than 450, when a scribe named Flavius Eutropius recorded that date in a surviving manuscript colophon.

Most scholars place its composition under Theodosius I (379–395), though recent work by another scholar, argues for Valentinian III (425–455).

Rather than resolving this impasse, contemporary research turns to what the Epitoma reveals about the Roman mind: its faith in institutions, its moralized approach to warfare, and its influence on later military thought.

Vegetius’ regulae bellorum generales (general rules of war), provided a bridge from the disciplined legions of Rome to the strategic manuals of Byzantium. Centuries later, Maurice’s Strategikon (late sixth–early seventh century) absorbed these lessons into a new imperial context, proving that the Roman “art of war,” distilled by Vegetius, survived the fall of the West.

His work remains a testament to a civilization that saw in warfare not only survival, but a moral duty — a craft that, in his own words, sustained all others.

The Immortal Manual: Vegetius and the Power of the Written Word

Vegetius’ faith in the supremacy of institutions led him to see military handbooks as essential instruments for governing the state. If victory, he reasoned, depends not on luck, cunning, or divine favor but on disciplina, training, and sound doctrine, then a written guide to reform becomes a tool of national preservation. For him, the handbook was not merely a book of tactics—it was the embodiment of Rome’s collective wisdom, meant to outlast generations.

The idea that history and didactic writing could serve practical ends was not new. Thucydides had declared that his work would be “a possession for all time,” its insights into human nature allowing future readers to foresee and avoid calamity. Polybius, too, saw in history a manual for life and politics:

“The knowledge of history is a very trustworthy education and training for political affairs, and the most excellent—even the only—teacher of being able to bear the changes of fortune nobly is the recollection of the misfortunes of others.”

Roman thinkers shared this belief. Sallust, echoing the old parallel between word and deed, argued that writing great actions was itself a form of doing them—a view later endorsed by Pliny in a letter to Tacitus. Yet Vegetius pushed this further than any of his predecessors. He cited Cato the Elder as proof that writing could serve the Republic even more than commanding armies:

“Cato the Elder, although he was unbeaten in war and had often led armies as consul, believed that he would be more useful to the Republic if he were to put down military discipline into writing. For deeds which are done bravely are of one age, but those things which are written for the benefit of the state last forever.”

In expressing this so forcefully, Vegetius elevated the military handbook to the level of law itself—an enduring structure that continued to shape society. The idea recalls Cicero’s De Officiis, where he praises the immortality of written service to the state, noting of Solon that

“Salamis benefited the state only once, but Solon’s laws will always benefit her.”

Vegetius adopted this reasoning but shifted the focus from the glory of the author to the immortality of the text. For him, permanence belonged not to the man but to the codified knowledge he left behind.

This transition—from celebrating heroic writers to venerating enduring texts—was a hallmark of late antiquity. In an age when sacred scripture and imperial law had come to dominate thought, written works were revered as repositories of order and truth. Vegetius placed military manuals within this sacred hierarchy, celebrating their power to preserve the state and ensure continuity. For him, military science itself was the foundation of civilization,

“the indispensable art, without which all other arts are not able to exist.”

("Vegetius' Epitoma Rei militaris:institutions, rules and reception" by Jonathan Hoyt Warner)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: