Villa Jovis: The Secret Lair for the Dark Pleasures of an Old Emperor

A luxurious villa in Capri is said to be the place where an emperor spent the last ten years of his reign, involved in sexual activities that would satisfy his disturbed imagination

Unlike other Campanian sites, Capri did not hold much historical significance before the early Roman Empire. One of the earliest mentions of the island comes from Emperor Augustus, who, enchanted by its beauty, exchanged the imperial island of Aenaria (modern Ischia) with the Neapolitans for Capri. On the island's north coast, in what is now the Marina Grande, Augustus built a villa. Tradition suggests that he also initiated the construction of Villa Jovis.

A Significant Archaeological Discovery

For many years, it was believed that the vaulted ruins beneath the chapel of Santa Maria di Soccorso and the foundations of a lighthouse were all that remained of the grand palace after its destruction by Corsairs in the Middle Ages.

However, Professor Amedeo Maiuri, superintendent of Antiquities in Campania, doubted this and his excavations confirmed that what was considered the palace's foundation was actually its top floor. On the side overlooking the Marina Grande, the remains of three additional lower floors were found, built around four large cisterns that formed the core of the palace's structure.

The path to Villa Jovis winds through the narrow streets of Capri village, then continues along a paved lane and shallow steps that lead upward toward the palace entrance. The route, passes through vineyards and fig orchards. Near the entrance, there is a steep drop from the limestone cliffs down to the water, nearly 330 meters (a thousand feet) below.

Credits: Jwslubbock, CC BY-SA 4.0

The main entrance, facing west and overlooking the Marina Grande, opens into an atrium where only the bases and sections of four cipollino marble columns remain. Off this atrium is a corridor with a simple white mosaic floor bordered by narrow black bands. A small door at the end of the corridor leads to the service areas, including the kitchen, servants' quarters, and the barracks for the emperor's guards. Near the end of the corridor is a wide staircase leading to the floor above. (Tiberius' Villa Jovis on the Isle of Capri, by Mary C. FitzPatrick, Barat College)

How to Access Villa Jovis

Villa Jovis is perched atop Monte Tiberio, offering stunning panoramic views of the island and the Bay of Naples. Accessing this historical site involves a scenic —but somewhat demanding— hike. Visitors typically begin their journey from Capri’s main town, Capri Town, which is about a 45-minute walk to the ruins.

Along the way, you’ll navigate through charming narrow streets and paths lined with lush Mediterranean flora, offering glimpses of the island’s beauty before reaching the villa.

Steps leading to Villa Jovis in Capri. Credits: Krisztian Juhasz from Getty Images, by Canva

To start your visit, you’ll follow signs pointing towards Villa Jovis from Capri Town’s Piazzetta, the island’s main square. The route leads you along Via Longano and later onto Via Tiberio, which steadily ascends towards the villa. The path is well-marked and easy to follow, but it’s essential to be prepared for the steep inclines, particularly towards the end of the walk, as the villa sits 330 meters (about 1,000 feet) above sea level. Comfortable walking shoes and water are highly recommended, especially during the warmer months.

The site itself is open to the public, with modest entrance fees, and the villa is open most days except for major holidays. Once you arrive, you’ll be able to explore the remains of Tiberius’ grand residence, including the cisterns, living quarters, and courtyards, all overlooking breathtaking views of the island’s cliffs and waters.

Be sure to take some time to admire the architecture and layout, which reflect both the grandeur of Roman imperial life and the strategic isolation Tiberius sought during his reign. Visitors often spend time soaking in the views and the history, making it a must-see for history buffs and nature lovers alike.

To ensure a smooth visit, it’s best to check the opening hours and entry fees before you go, as these can vary seasonally. You may also consider visiting early in the day to avoid crowds and the heat, especially if you’re visiting during summer. While the climb can be a bit challenging, the reward of experiencing one of the Roman Empire’s most intriguing imperial residences, combined with Capri’s natural beauty, makes it a memorable adventure.

Credits: Krisztian Juhasz from Getty Images, by Canva

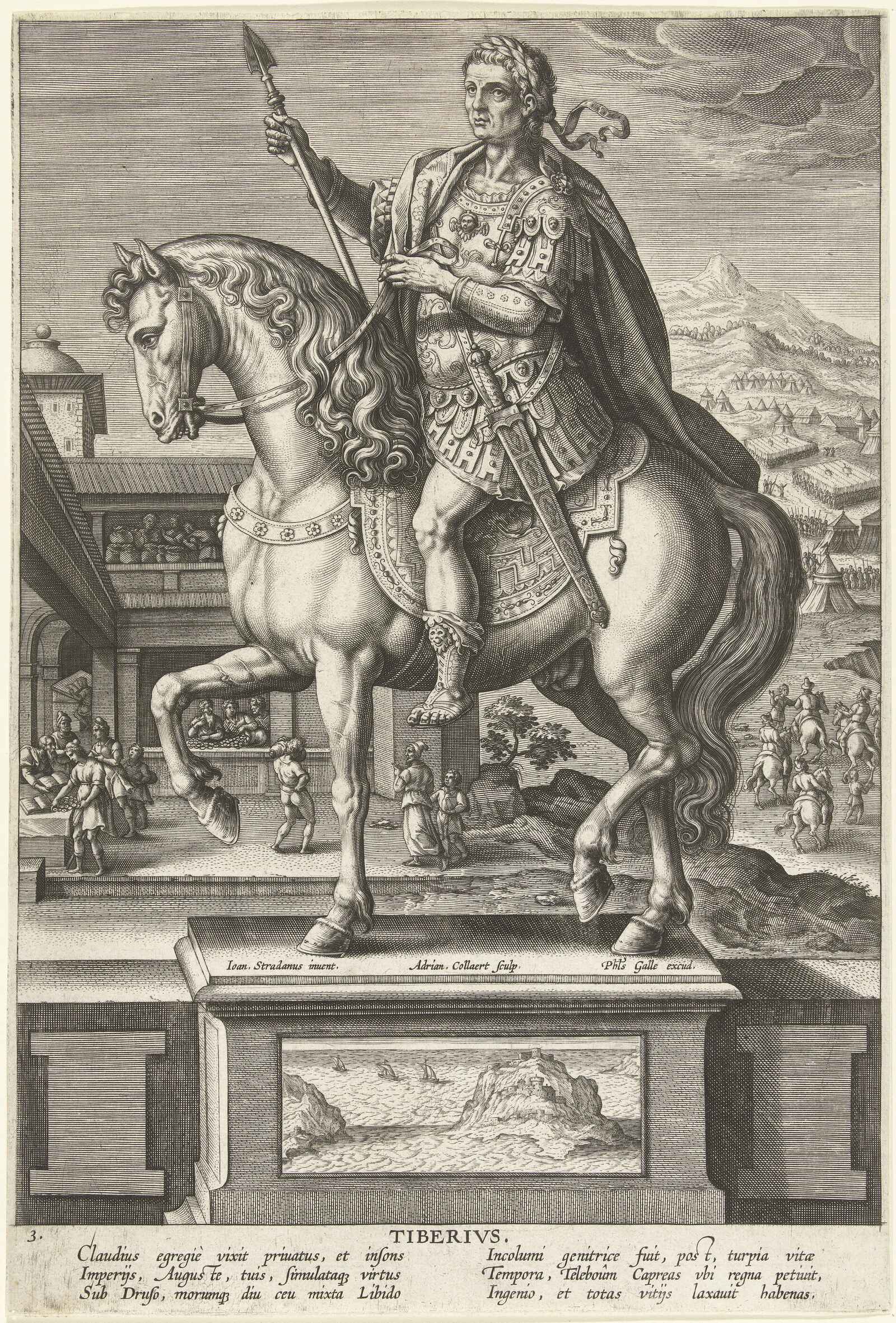

The Retreat of a Peculiar Emperor

It is not sure who started building The Villa of Jupiter (Villa Jovis). According to Strabo, it was Emperor Augustus who purchased the island of Capri (ancient Capreae) from Naples and established the first imperial residence there By the end of Tiberius’ reign, Tacitus records that there were at least a dozen imperial buildings on the island.

Some of these were likely taken over from previous owners and adapted for imperial use, while others were newly constructed. Of the discovered sites, the most impressive is the villa on the eastern height, near the church of S. Maria del Soccorso, identified as the "Villa Iovis" mentioned by Suetonius.

Although only a few buildings from the Augustan and Tiberian periods have been definitively identified, the remains suggest that Tiberius' imperial establishment on Capri was quite extensive. Several villas were present, and some were notably large.

For example, the main block of Villa Jovis alone covers about 5,400 square meters (±58,000 square feet), not including possible upper floors. The "Palazzo a Mare" stretches along cliffs for over 550 meters (±600 yards), while the Damecuta Villa extends for 140 meters (153 yards) along a cliff and includes a main block covering more than a thousand square meters. To put these sizes into perspective, the Domus Tiberiana on Rome's Palatine Hill (excluding later additions) measures around 16,000 square meters (±172,000 square feet).

Thus, Villa Jovis' main block alone was about a third of the size of Tiberius' palace in Rome.

Tiberius’ palace in the Roman Forum, Rome. Credits: Anton Aleksenko from Getty Images, by Canva

Considering the outbuildings, gardens, and other villas on Capri, the entire island effectively functioned as a vast imperial residence. Inscriptions reveal that Tiberius had a large household staff in Rome, and it is reasonable to assume a similarly extensive staff on Capri. This is supported by the size of the kitchen at Villa Jovis, which included about a dozen stoves and a baker’s oven, indicating the need to feed a large number of people.

Tiberius' interests and activities after 27 AD closely mirrored those of other Romans who spent time in Campania, reflecting the norms of his era, though with his own unique twist. He enjoyed discussions about literature and even wrote poetry and memoirs after 31 AD. The presence of several villas on Capri suggests that, like other Romans, Tiberius moved between villas and traveled frequently to the mainland, visiting imperial villas in places like Surrentum, Antium, and Misenum.

While there is no direct mention of Tiberius' involvement in fish-raising, the existence of fish farms at places like Sperlonga, which he visited, hints at his possible interest. Additionally, Tiberius may have sought the health benefits of Campania's spas and baths.

Tacitus suggests that he left Rome due to embarrassment over his appearance, and it's plausible that Tiberius hoped the region's sulfur baths or seawater might improve his health. The Villa Jovis had ample water storage and a large bath complex, and it's likely that Tiberius took advantage of the region's healing waters.

Tiberius’ relocation to Campania was not unusual, as other prominent Romans, such as Marius, Pompey, and Caesar, also built villas with commanding views. Like them, Tiberius entertained guests, and the island probably had extensive gardens and seaside grottoes. His retreat to Capri resembled the behavior of other wealthy Romans, who often sought refuge from the pressures of Rome in Campania.

What stands out, however, and what prompted comments from historians like Tacitus, Suetonius, and Dio, is that Tiberius never returned to Rome despite visiting nearby areas, and he chose the relatively unfashionable Capri for his retirement. (Tiberius on Capri, by George W. Houston)

The Dark Side of Villa Jovis

According to two prominent Roman historians, Tiberius Caesar engaged in unspeakable acts of debauchery on the island of Capri during the final decade of his life. Tacitus and Suetonius give specific accounts of these actions in two brief passages.

“Cn. Domitius and Camillus Scribonianus had embarked on the consulship when Caesar, having crossed the strait which washes between Capri and Surrentum, was skirting Campania, in two minds whether to go into the City—or, because he had already decided otherwise, simulating a scene of impending arrival.

And, having landed often in the neighborhood and approached the gardens by the Tiber, he retreated again to his rocks and the solitude of the sea, in shame at the crimes and unbridled lusts with which he was so inflamed that, in the manner of a king, he polluted freeborn youngsters in illicit sex.

Nor was it only good looks and becoming bodies but in some cases boyish modesty and in others the images of their ancestors which acted as the incitement of his desire.

And that was the first time that the previously unknown designations of “sellarii” and “spintriae” were devised, respectively from the foulness of their place and their multifarious passivity.

And the slaves who were charged with the searching and bringing resorted to gifts for the ready, threats against the reluctant and, if a relative or parent held them back, violent seizure, as though their victims were captives.”

Tacitus, Annals

On the same subject, Suetonius writes:

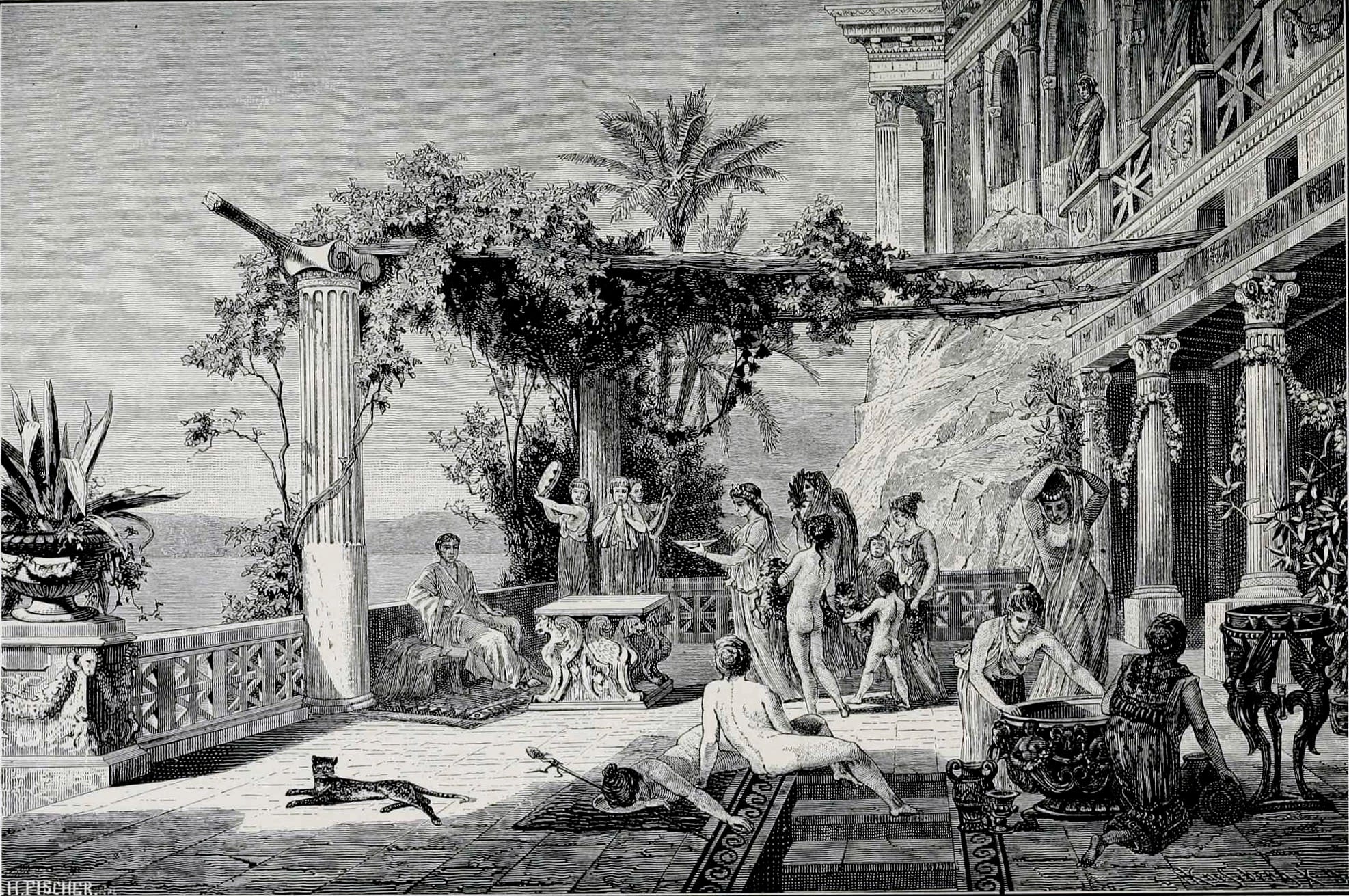

“On retiring to Capri he devised “holey places” as a site for his secret orgies; there select teams of girls and male prostitutes, inventors of deviant intercourse and dubbed analists, copulated before him in triple unions to excite his flagging passions.

Its many bedrooms he furnished with the most salacious paintings and sculptures and stocked with the books of Elephantis, in case any performer should need an illustration of a prescribed position.

Then in Capri’s woods and groves he contrived a number of spots for sex where boys and girls got up as Pans and nymphs solicited outside grottoes and sheltered recesses; people openly called this “the old goat’s garden,” punning on the island’s name.”

Both Tacitus and Suetonius describe in graphic detail how Tiberius allegedly indulged in extreme forms of sexual gratification. According to these accounts, Tiberius filled his villa with an array of young men and women—referred to as spintriae—and orchestrated elaborate sexual performances.

Suetonius claims that Tiberius set up two distinct spaces for these activities: the Sellaria, an indoor venue resembling a brothel, and the Caprineum, an outdoor space where individuals dressed as mythological creatures, like Pans and nymphs, solicited outside caves and secluded spots on the island.

Tacitus adds that Tiberius’s behavior included corrupting young freeborn boys and that this debauchery became so extreme that new terms, sellaria and spintriae, were coined to describe these acts. He notes that the spintriae were connected by their willingness to engage in various sexual acts before the emperor, serving to arouse his waning desires.

In addition to the sexual nature of these activities, Tiberius's villa was reportedly adorned with explicit art and erotic manuals, such as those attributed to Elephantis, to serve as guides for the participants. The sexual performances in the Villa Jovis, while often recounted as acts of voyeurism and staged group encounters, also underscore Tiberius's fascination with mythological role-play, blending sexual liberation with elaborate theatrical settings.

The argument in favor of mixed-sex performances at Villa Jovis during Tiberius Caesar’s reign highlights some key points about his alleged preferences. Contrary to common assumptions, Tiberius did not show much interest in men as sexual objects, with only one questionable anecdote in Suetonius referencing an alleged double rape. His preferences, after decades of a relatively conventional domestic life, appear to have leaned in other directions. Thus, it would be odd for him to have an all-male troupe of prostitutes, especially given that the notorious books of Elephantis, which were present at Villa Jovis, focused entirely on heterosexual acts.

The used term spintria, in the original text, often translated as "male prostitute," should instead refer to female sex workers or individuals who were sexually passive or bisexual, participating in mixed-sex performances. The performers, referred to by Tiberius as "bracelet workers," were involved in group sexual acts where they would be penetrated in multiple ways, resembling human bracelets. A proper translation of Suetonius should thus read:

“Upon retiring to Capri, he devised the Sellaria as a site for his secret orgies: there, select teams of girls and mature catamites, along with inventors of deviant intercourse, whom he called ‘bracelet workers,’ copulated before him in triple unions to excite his flagging passions.”

Tacitus and Suetonius both emphasize that the participants were young and attractive, with some freeborn and of noble birth, and there is no indication that these individuals were professionals. Instead, they were often unwilling victims of a tyrant’s desires. The one named spintria, Aulus Vitellius, fits this description perfectly, being young, freeborn, and highly placed, suspected of having secured his father's rise in rank at the cost of his own chastity.

Tiberius treated these well-born youths as prostitutes, degrading them further by creating neologisms from the language of prostitution, like the aforementioned sellaria and spintriae. Notably, both Suetonius and Tacitus present Tiberius as a voyeur rather than an active participant in the acts, using the spectacles to arouse his failing libido. The villa was filled with obscene artworks and sex manuals, which the performers could consult as guides to enact the specified postures, making them akin to actors in a pornographic film.

Thus, Tiberius’ infamous sexual spectacles at Villa Jovis, were likely staged as grand theatrical performances involving both male and female participants, directed by Tiberius as a detached observer.

A possible representation of Emperor Tiberius in Villa Jovis. Illustration: Midjourney

The performative nature of Tiberius's activities on Capri places them not only within the context of Roman sexual customs but also within broader cultural trends of the time. One such trend was the Roman elite's love for creating fantasy environments, known as the "landscape of allusion." Wealthy Romans recreated real or fictional locations in their villas, transforming their surroundings with buildings, art, and landscapes.

For example, Cicero's villa at Tusculum and Hadrian's near Tibur featured replicas of famous places like Athens and Egypt. Capri, as the private refuge of emperors, followed this tradition, with Augustus setting the tone by naming a nearby islet "Apragopolis," or "City of Leisure." Tiberius' Villa Jovis, along with its features like the replica of the Pharos of Alexandria and the mock-brothel Sellaria, fit comfortably into this performative, ostentatious landscape.

A second relevant practice was the Roman fondness for elaborate mythological role-playing at banquets, where guests or hosts would dress up as gods or mythological figures. These activities could involve freeborn and noble youths, not just professional entertainers, and the scenes could be staged in the natural settings of the villa, like woods or caves on Capri.

Third, Tiberius’ activities align with the practice of mock brothels, where respectable Roman women or youths, including freeborn individuals, would temporarily role-play as sex workers. This was a favorite pastime of later emperors like Caligula and Nero, but the tradition had earlier roots. These events may not always have been full orgies, but they certainly involved risqué performances. Tiberius’ Sellaria on Capri likely followed this tradition, with young nobles and freeborn individuals participating in staged sexual encounters, while the emperor watched as a voyeur.

Capri offered a place where Roman elites could shed the restrictions of both public and private life, indulging in pure idleness (desidia). Augustus had already set the tone by mandating that Romans wear Greek dress and speak Greek on the island. Suetonius reports that when Gaius Caligula was summoned to Capri in 31 CE, Tiberius indulged his passion for theatrical arts, hoping it might soften his cruelty.

This emphasizes that, on Capri, sexual liberation, costume, and role-playing were as much about performance and theatre as they were about indulgence.

A graffiti of Roman Theatre masks, outside of the Roman Theatre in Lisbon, Portugal. Credits: George Liapis

In summary, the "dark pleasures" of Tiberius on Capri, while scandalous in nature, were deeply rooted in the broader Roman cultural fascination with theatrical performance, role-playing, and the creation of fantasy worlds. There remains a possibility that some participants might have been more willing and perhaps even enjoying themselves in these staged scenarios, despite the negative portrayal by ancient historians. (Sex on Capri, by Edward Champlin. Transactions of the American Philological Association)

Tiberius and the Roman Sex Culture

Tiberian sexuality necessitates the creation of new terms (sellaria, spintria) to describe it, as well as the collection of ancient paintings and obscure books to give it structure. Prostitutes are gathered from all over, and dehumanized children (pisciculi, Panisci) are integral to its expression.

There is an infamous passage in Suetonius analysed below which, while well-known, has not been thoroughly studied beyond certain linguistic and sexual puzzles. Tiberius’ affinity for Greek culture and the obscure partially explains some of Suetonius’ details. Likewise, references to brothels, erotic art, and elite Roman gardens provide context for parts of the narrative. However, these elements alone do not fully capture the disturbing horror of Suetonius’ depiction of Tiberius’ Caprineum.

Tiberius' sexual desires distort and blur the boundaries of Roman sexuality. Bodies are manipulated and redefined, becoming mere replications of images from art. Children are transformed into little fish or hybrid deities, erasing the normal stages of human development.

In Tiberius' world, sexuality becomes a chaotic mixture of extreme performances, defying traditional Roman sexual categories. Suetonius portrays Tiberius with traits of the god Priapus, emphasizing the emperor’s destructive and perverse sexuality, aligning it with nefas (moral outrage) and horror.

“Still with a greater and more base infamy was he enflamed that it is hardly appropriate to be discussed or heard let alone to be believed, as if he were raising boys of the tenderest age, whom he called pisciculi (little fishes), to turn about and play between his thighs as he swam, gently grasping at him with their tongues and nibbles.

And even as the children became stronger, though not yet weaned from breast milk, he would bring them to his genitals as though to a nipple, clearly being more prone to this kind of desire both because of their nature and age.”

Suetonius

In Suetonius’ account, the sexual practices on Capri, rather than uniting, fragment and dehumanize the participants. Monstrous transformations and dehumanization are central to these passages, where voyeurism becomes necessary to fully grasp the horrifying imagery that Suetonius presents.

“Rooms arranged in different ways he adorned with painted tablets and figurines of the most lascivious images and statues, and he equipped them with the books of Elephantis so that for the performance of sexual deeds an example of a desired sex position might be available for anyone.”

Suetonius

Many aspects of Suetonius' narrative draw from common elements of Roman sexual culture, such as brothels, prostitutes, sex manuals, erotic art in homes, pederasty, and elite garden spaces. However, Suetonius reinterprets these elements in a way that dehumanizes them and presents them as dangerous.

Sections 43-44 are unsettling as they emphasize that Roman sexuality is deeply tied to physical embodiment. Tiberius' influence on sexual expression becomes so overpowering that it transforms and degrades the bodies around him, making them permeable to his desires. All bodies, except for Tiberius’, become abject and distorted, although his own body also undergoes changes.

These sections explore the extremes and boundaries of Roman sexuality. While the Pan-goat sculpture imbues its divine-animal union with human qualities, Tiberius' version of sexuality deconstructs and fragments traditional Roman sexual norms, reshaping them in a way that reveals a destructive and pathological aspect of his behavior. On Tiberius' Capri, nothing remains human.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: