The Spartan Who Saved Carthage – and Broke a Roman Invasion

In 255 BCE, as Rome advanced toward Carthage itself, a Spartan mercenary took command of a collapsing army. One battle later, the Roman invasion lay in ruins — and Xanthippus vanished from history almost as suddenly as he had appeared.

Before Hannibal became Rome’s most famous enemy, another foreign commander forced the Republic to confront an uncomfortable truth. In North Africa, at a moment when victory seemed within reach, Rome’s legions met a battlefield they did not understand – and a strategist who understood them all too well.

From Treaties to Messana – How Rome and Carthage Collided

In the early centuries of Rome’s expansion, Carthage and Rome were not natural enemies. Treaties signed as early as 508 BCE and again in 348 BCE regulated trade and recognised separate spheres of influence. At the time, Rome was still a regional Italian power, and the agreements largely favoured Carthage, whose commercial reach far surpassed Rome’s modest interests.

As Rome consolidated control over Italy in the third century BCE, the strategic distance between the two powers narrowed. External pressures accelerated this shift. Agathocles of Syracuse operated in southern Italy in 293 BCE, and soon after, Pyrrhus of Epirus entered Italy and later Sicily, briefly challenging both Roman and Carthaginian interests. Despite these tensions, neither state sought direct confrontation with the other.

The turning point came in 264 BCE, when Rome intervened at Messana in Sicily. What had previously been a Carthaginian-aligned city became the flashpoint of a broader struggle. Roman confidence, opportunism, and fears of Carthaginian influence in Italy combined with Carthaginian concern over shifting power balances in Sicily. The result was the First Punic War – a conflict neither side appears to have originally intended, yet one that escalated into the largest war the Mediterranean had yet seen.

The war was marked by massive losses and unexpected reversals. Rome, inexperienced at sea, rapidly built fleets and achieved naval victories at Mylae (260 BCE) and Cape Ecnomus (256 BCE), yet also suffered catastrophic storm losses. On land, the Roman legions failed to expel Carthage from Sicily. In 256 BCE, Rome carried the war into Africa, winning at Adys and capturing Tunis, but failed to consolidate revolts among Carthage’s Numidian subjects.

In 255 BCE, Carthage turned to a Greek mercenary commander – Xanthippus – whose tactical reforms led to the destruction of the Roman army in Africa. The conflict dragged on until 242 BCE, when Rome defeated the Carthaginian fleet at the Aegates Islands. Cut off from supply, Carthage accepted peace, surrendered Sicily, and paid a heavy indemnity.

What began as a dispute over a single Sicilian city had become a struggle that reshaped the western Mediterranean. (“General history of Africa II. Ancient civilizations of Africa” Editor: G. Mokhtar)

A Century of Rivalry – The First Punic War as Prolonged Strategic Competition

The three Punic Wars (264–146 BCE) formed a century-long struggle between Rome and Carthage, but the First Punic War (264–241 BCE) set the pattern. It began as a regional dispute over Sicily and developed into a prolonged contest between a rising land power and the dominant maritime state of the western Mediterranean.

Rome’s consolidation of Italy in the fourth and early third centuries BCE brought it into closer contact with Sicilian trade routes and power politics. Carthage, long engaged in rivalry with Syracuse for influence on the island, viewed Roman intervention at Messana in 264 BCE as a dangerous shift in the balance of power.

What followed was not a short campaign but a drawn-out strategic competition shaped by fluctuating fortunes, costly innovation, and shifting alliances.

The war moved across Sicily, North Africa, and the open sea. Rome, inexperienced at naval warfare, built fleets from scratch and achieved early victories, including the capture of Agrigentum and major successes at sea. Yet storms destroyed entire Roman fleets, and Carthage regained momentum through maritime supply lines and the hiring of experienced mercenaries such as Xanthippus. Sicily became a theatre of siege, counter-siege, and stalemate, while both powers rebuilt, adapted, and endured repeated reversals.

Only in 241 BCE, when a privately financed Roman fleet destroyed a Carthaginian relief force at the Aegates Islands, did the stalemate break. Isolated and exhausted, Carthage accepted peace, surrendering Sicily and paying a heavy indemnity. Yet the rivalry was not resolved. The interests that had driven both states into conflict remained intact, ensuring that competition would resume in later decades. ("Polybian Warfare The First Punic War as a Case Study in Strategic Competition and Joint Warfighting" By Casey B. Baker)

The African campaign was the moment Rome learned that the war could reach beyond Sicily – and it was also the moment a single outsider briefly reshaped Carthage’s battlefield decisions

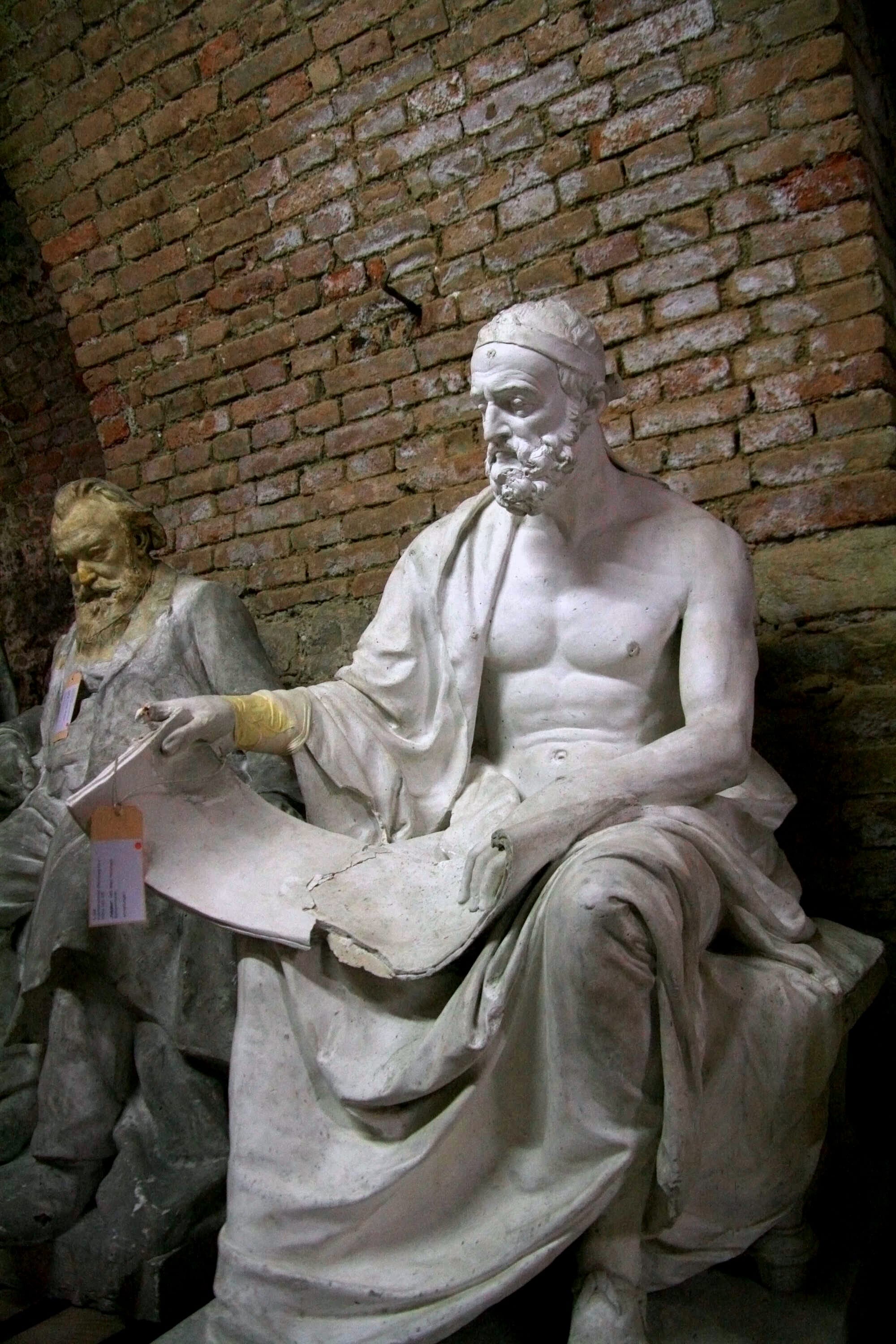

Xanthippus – The Outsider Who Took Command at Carthage

Carthage relied heavily on hired soldiers, but it still tended to reserve the highest commands for its own citizens. Senior posts often clustered in established families, forming something like a lasting military aristocracy. That pattern appears to have held until the First Punic War – and then, in 255 BCE, it briefly broke. For that single moment in the conflict, Carthage placed a foreigner in overall command. His name was Xanthippus.

Ancient writers agree on only one firm point about him: he was a mercenary from Lacedemonia (Sparta). Beyond that, his background and career are uncertain. The sources disagree on how he arrived, what status he held before reaching Africa, and what exactly led to his sudden promotion – and they are equally unclear about what became of him after his victory. Still, even with these gaps, there is enough surviving material to set his appearance in context and to compare the different traditions that try to explain who he was.

By the time Xanthippus enters the narrative, the war had already produced major Roman successes. Rome had taken Akragas in 262 BCE and won its first great naval victory at Mylae in 260 BCE. Yet even after securing Syracuse as an ally under Hiero II, Rome could not drive Carthage out of Sicily or force a decisive end to the fighting.

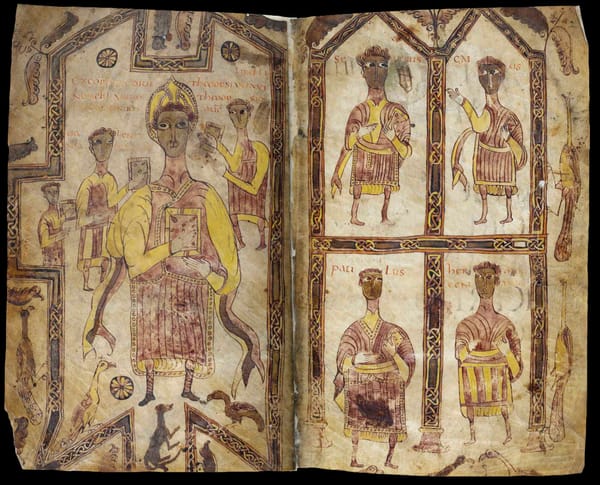

“Just about this time there arrived at Carthage one of the recruiting-officers they had formerly dispatched to Greece, bringing a considerable number of soldiers and among them a certain Xanthippus of Lacedaemon, a man who had been p91 brought up in the Spartan discipline, and had had a fair amount of military experience.

On hearing of the recent reverse and how and in what way it occurred, and on taking a comprehensive view of the remaining resources of the Carthaginians and their strength in cavalry and elephants, he at once reached the conclusion and communicated it to friends that the Carthaginians owed their defeat not to the Romans but to themselves, through the inexperience of their generals.

Owing to the critical situation Xanthippus's remarks soon got abroad and reached the ears of the generals, whereupon the government decided to summon him before them and examine him.

He presented himself before them and communicated to them his estimate of the situation, pointing out why they were now being worsted, and urging that if they would take his advice and avail themselves of the level country for marching, encamping and offering battle they could easily not only secure their own safety, but defeat the enemy.

The generals, accepting what he said and resolving to follow his advice, at once entrusted their forces to him” Polybius, The Histories

The Roman solution, as the sources present it, was to shift the war’s centre of gravity to Africa – a move that echoes the earlier precedent of Agathocles, who had attacked Carthage’s home territory to relieve pressure on Sicily. Polybius highlights the scale of Roman adaptation at this stage, noting reforms and reorganisation that made the expeditionary force ready to fight both at sea and on land.

After a Roman victory near Cape Tyndaris, the Roman fleet could cross the Mediterranean, and Carthage faced a new danger: the war had reached its own territory. The Romans did not immediately attempt to blockade Carthage itself. Instead, they took Aspis, turned it into a base, and used the surrounding countryside to supply their operations.

The sources emphasise the speed with which the campaign became destructive: raids and plundering brought in livestock and prisoners and widened the crisis beyond the battlefield.

At this point, Rome split its army. One part returned home; the remainder stayed in Africa under the consul Gaius Atilius Regulus. Polybius reports that Regulus besieged Adys, defeated the Carthaginians again, and then moved toward Tunis, close enough to sharpen the sense of immediate threat. The situation worsened further as Numidian groups exploited the moment, raiding the countryside and intensifying the supply crisis.

In this picture, Rome’s advance and Numidian unrest combine to strain Carthage’s ability to feed both city and rural populations.

It is against this backdrop – military defeats, territorial pressure, internal instability, and failed negotiations – that Xanthippus becomes visible. But the sources cannot agree on how. Polybius claims Carthage had already sent recruiters to Greece, and that Xanthippus arrived among other mercenaries. Hearing the situation, he is said to have analysed Carthaginian failures aloud, spoke with such confidence that his comments reached the generals, and was then summoned, consulted, and ultimately placed in command.

Appian instead describes a more formal request: Carthage sent to Sparta specifically for a commander, and Sparta sent Xanthippus. Diodorus presents him as a soldier who pressed the generals to fight and offered himself as commander. Cassius Dio goes even further, portraying his rise as an assumption of authority not only over the army but almost over the city itself. Cicero, meanwhile, compresses the story into a brief label, calling him a Spartan commander serving under Hamilcar Barca.

Because his earlier life is undocumented, later writers and modern scholars are left to infer what kind of man he might have been. Polybius and Cassius Dio both hint that he was not aristocratic, describing him as emerging from the mercenary ranks and, in Dio’s case, explicitly calling him low-born and implying Carthaginian contempt for a Greek outsider.

Nothing reliable can be said about when he was born, where he was raised, or whether he held citizen status at Sparta. The text also stresses the problem of timing: Xanthippus lived in the Hellenistic period, when Sparta’s society and military system were no longer identical to the older classical model, and when mercenary service had become increasingly common across the Greek world.

Even so, whatever his origin, the fact that Carthage trusted him with supreme command suggests experience and credibility. He does not read as a newly trained recruit. The narrative assumes a man already practised in warfare and capable of directing troops.

The sources also associate him with active battlefield leadership, including movement on horseback. Diodorus describes him riding across the field, rallying men and even physically intercepting fugitives to send them back into the fight.

“During the battle Xanthippus, the Spartan, rode up and down, turning back any foot-soldiers who had taken flight. But when someone remarked that it was easy for one on horseback to urge others into danger, he at once jumped down from his horse, handed it over to a servant, and going about on foot, begged his men not to bring defeat and destruction upon the whole army.” Diodorus Siculus, Library of History,Fragments of Book XXIII

That raises practical questions the tradition cannot answer – whose horse he rode, whether he had cavalry training, and how common such skills were for a Spartan or Greek mercenary commander of this period.

The discussion expands naturally into the wider evolution of warfare: hoplite equipment was changing, Macedonian influence had reshaped infantry tactics, and cavalry had become increasingly important across Hellenistic battlefields. The text also points out that Carthage had access to highly distinctive cavalry in its Numidian allies, and the ability to combine such forces with elephants and mixed infantry made its armies unusually complex to command.

That complexity matters for understanding why Xanthippus could be presented as decisive. Polybius has him training the army before battle, which implies not just tactical knowledge but an ability to work quickly with a multi-ethnic force – Balearic slingers, Numidian cavalry, elephants, and Greek mercenaries among others – each with different roles.

“Now even when the original utterance of Xanthippus got abroad, it had caused considerable rumour and more or less sanguine talk among the populace, but on his leading the army out and drawing it up in good order before the city and even beginning to manoeuvre some portions of it correctly and give the word of command in the orthodox military terms, the contrast to the incompetency of the former generals was so striking that the soldiery expressed their approval by cheers and were eager to engage the enemy, feeling sure that if Xanthippus was in command no disaster could befall them.

Upon this the generals, seeing the extraordinary recovery of courage among the troops, addressed them in words suitable to the occasion and after a few days took the field with their forces. These consisted of twelve thousand foot, four thousand horse and very nearly a hundred elephants.” Polybius, The Histories

Zonaras adds a key tactical detail: Xanthippus avoided fighting in broken or higher ground and brought the battle onto plains, where cavalry and elephants could operate most effectively. This choice of terrain becomes part of the explanation for Carthage’s reversal of fortunes.

The battle itself is framed as an interaction between numbers, formation, and conditions. Polybius gives Carthage 12,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry, and close to 100 elephants, while Rome has 15,000 infantry but only about 500 cavalry. Rome’s infantry advantage could not compensate for Carthage’s overwhelming mounted superiority and its elephant corps.

Xanthippus placed elephants at the front, heavy infantry behind, and cavalry and light troops on the wings. Regulus positioned light infantry forward, heavy infantry behind, and cavalry on the wings, trying to blunt the elephant threat. Polybius suggests the Roman formation could absorb elephants but at the cost of exposing itself to encirclement by cavalry. In this reading, cavalry becomes the decisive instrument, not necessarily because Carthaginian riders were inherently superior, but because Rome had too few to resist them.

That interpretation has consequences. It undercuts the idea that Carthage’s own commanders were uniquely incompetent. The text insists that Carthage had long produced effective generals and continued to win battles in Sicily and elsewhere. It also reminds the reader that Carthaginian tactics after Mago’s reforms had already moved closer to Greek-style methods, so Xanthippus’ approach was not alien in principle.

His appointment, then, may require an explanation beyond simple “foreign genius replacing failed locals.” The passage proposes several possibilities: perhaps he was unusually well-known among mercenary circles; perhaps his value lay in morale and confidence at a crisis point; perhaps Polybius’ narrative shape elevates him for moral and literary reasons (the arrogance of Regulus, the reversal of fortune, the lesson about seizing opportunities).

Another possibility is more administrative: Xanthippus may have been an already influential subordinate whose name only surfaced because the story needed a recognisable agent for the victory.

After the battle, the sources present dramatic results: Carthage suffered relatively light losses, Rome was shattered, prisoners were taken, and Regulus himself was captured. Xanthippus is credited with saving Carthage from immediate danger and helping force Rome’s retreat from Africa – though the text also stresses that Roman logistical difficulties and shortages were already a major threat to the expedition.

Then the tradition fractures again. Polybius says Xanthippus left Carthage soon afterward, judging the decision sensible because success would provoke envy and he lacked the social protection of family and allies in a foreign city. Polybius hints at other versions but never returns to them. Diodorus offers a more elaborate tale: Xanthippus goes back to Sparta, recruits more men, travels to Sicily, wins again, and is then drowned through treachery.

Cassius Dio preserves two similar ship stories: either Carthaginians pursued and sank him, or they supplied a defective ship that he avoided by switching vessels. Appian also reports deception at sea, claiming the Carthaginians disposed of him and his companions by throwing them overboard. Across these versions, jealousy is the recurring explanation – the victorious outsider becomes a liability.

That raises an obvious puzzle: why would Carthage eliminate a commander who had saved the city, rather than retain him for the rest of the war? The text offers practical pressures. Mercenary commanders could be dangerous, and Mediterranean history supplied plenty of examples of mercenary bands turning into threats. Carthage also faced financial strain, and later events (including the Mercenary War) suggest serious difficulties in paying troops.

Some accounts imply that non-payment or the need to discharge mercenaries may have contributed to Xanthippus’ removal, whether by dismissal, deception, or violence.

Finally, the passage turns to a striking possibility: a later cuneiform chronicle from the Ptolemaic world mentions a commander named Xanthippus active in Mesopotamia in the 240s BCE, serving Ptolemy III. The chronology could, in theory, fit a survivor of the African campaign who later sought employment in the eastern Mediterranean. But the identification cannot be proven.

The name may be coincidental, and even if it is the same man, there remains a long gap where nothing is known. ('Xanthippus of Laecedemonia: a foreign commander in the army of Carthage" by Dantas, Daniela)

Xanthippus enters the record at a moment of crisis, reshapes a battlefield, captures a Roman consul, and then recedes into uncertainty. Whether dismissed, betrayed, or simply pragmatic enough to leave before envy turned dangerous, he remains one of the most elusive figures of the First Punic War. For a brief interval, Carthage entrusted its survival to a foreign commander — and Rome learned that even its legions could be undone when cavalry, elephants, terrain, and leadership converged against them. What endures is not a biography, but an episode: a single campaign in which the balance of the Mediterranean shifted because an outsider understood how to use the army before him.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: