The Religion of Ancient Rome: How Romans Worshipped Their Gods

In ancient Rome, religion was a public duty, not a private creed. Through ritual, sacrifice, and the worship of countless gods, Romans sought divine favor to sustain both state and soul, blending piety, power, and tradition into the fabric of empire.

Religion in ancient Rome was not a matter of faith alone—it was a system of order, obligation, and fear. The Romans lived under the gaze of countless gods, each demanding attention through ritual and sacrifice. Every temple, vow, and procession served to maintain harmony between heaven and earth.

To honor the gods was to protect the state; to neglect them was to invite disaster. In this world of divine exchange, worship was less about devotion than duty—a careful negotiation between mortal and immortal powers that defined Roman life.

Hidden Gods: The Allure of Mystery Cults in Rome

Roman religion, at its core, was collective, public, and procedural. Its strength lay in tradition and repetition—rites performed for the welfare of the community, not the salvation of the individual. Yet, as Rome expanded and absorbed new peoples and beliefs, a quiet transformation began to take place.

Beneath the public rituals of Jupiter and Mars, another kind of worship flourished—one that offered personal meaning, emotional depth, and the promise of renewal beyond death. These were the mystery cults: sacred communities whose rites were reserved for the initiated and whose doctrines were spoken only in whispers.

The Romans did not invent mystery religion. They inherited it, first through contact with Greece and later from the lands of the East. The Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Persephone in Greece, long celebrated as the archetype of initiation, profoundly influenced Roman attitudes toward divine secrecy.

In Rome, similar ideas took root in the cults of Isis, Mithras, Cybele, Dionysus, and others. These faiths did not reject Roman religion; rather, they complemented it by satisfying a spiritual need that public worship left unanswered—the longing for personal connection with the divine and assurance in the face of mortality.

Participation in the mysteries was voluntary and inclusive. Initiates came from all ranks—men and women, slaves and free citizens. Each cult offered a structured process of initiation, purification, and revelation. Candidates often underwent fasting, ritual bathing, or symbolic trials representing the passage from ignorance to enlightenment.

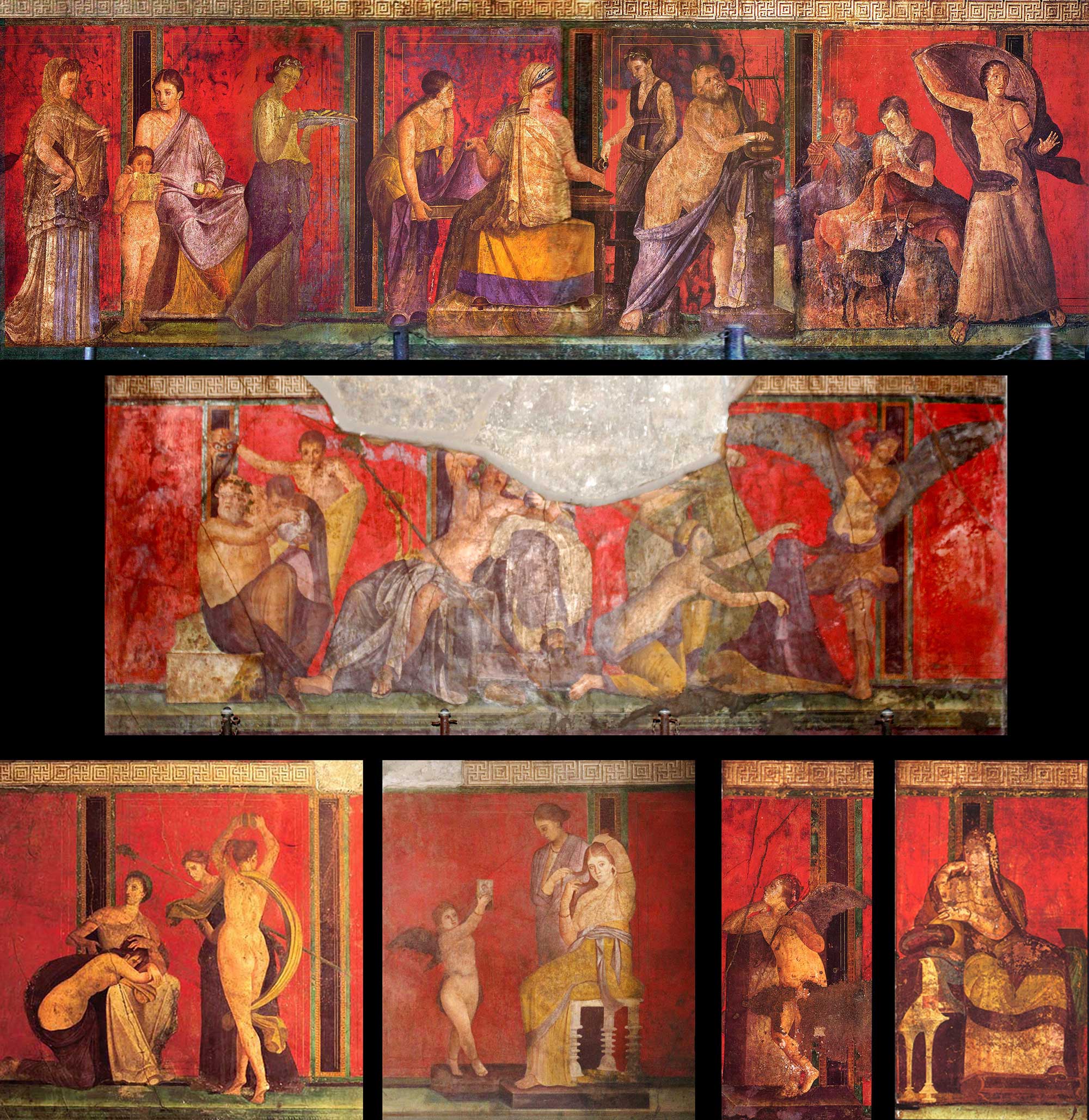

The ceremonies took place in private sanctuaries, often underground or enclosed, symbolizing a descent into the divine realm. There, under the dim light of torches, initiates witnessed reenactments of sacred myths: the death and rebirth of gods, the victory of light over darkness, or the restoration of cosmic harmony.

In the cult of Isis, brought from Egypt but reshaped in Roman form, the goddess was venerated as a universal mother and protector. Her worship centered on purification, renewal, and the triumph of life over death. Initiates experienced her mysteries as a passage from suffering to salvation, guided by her compassion and power to heal. The rituals, described in later sources, emphasized secrecy and moral transformation—the initiate emerged renewed, bound to Isis by loyalty and gratitude.

The cult of Mithras, favored among soldiers, offered a different experience. Its temples, the mithraea, were built like caves and adorned with images of Mithras slaying the cosmic bull—an act believed to sustain the universe. The symbolism of the tauroctony was complex: sacrifice, creation, and the victory of order over chaos.

The initiates, organized into grades of rank, underwent successive stages of instruction and testing. Their initiation was both communal and individual, marking entry into a brotherhood that promised strength, solidarity, and immortality of the soul.

Other mystery religions—those of Cybele and Attis, Dionysus and Sabazius—combined ecstatic celebration with ritual discipline. Their ceremonies blended foreign and local traditions, absorbing elements of Phrygian, Greek, and Roman worship.

They shared a common language of transformation: through ritual suffering and symbolic death, initiates were promised participation in divine renewal. Music, dance, and sacred drama transported the worshipper beyond the boundaries of ordinary piety, offering a glimpse of the eternal order behind visible life.

Despite their secrecy, these cults were not considered subversive as long as they coexisted peacefully with the state religion. The Roman government viewed them pragmatically. The Senate might restrict rites that provoked disorder or violated decorum—as in the suppression of the Bacchanalia in 186 BCE—but over time most mystery religions were accepted, even patronized by the elite.

Their expansion mirrored the empire’s own diversity, blending traditions into a shared spiritual vocabulary. By the imperial age, temples to Isis stood beside those of Jupiter, and mithraea spread from Britain to Syria, from the Rhine frontier to North Africa.

The appeal of mystery religion lay in its emotional immediacy. Public worship sought harmony between gods and state; the mysteries promised harmony between gods and soul. They taught not doctrine but experience—the sense of being chosen, purified, and reborn.

Their ceremonies assured participants that divine power was not remote but present, accessible through ritual knowledge and personal devotion. For many Romans, this intimacy with the sacred offered comfort in an age of uncertainty, when the old gods seemed too distant to answer private fears.

In time, these currents of spiritual individualism would reshape Roman thought. The language of salvation, purification, and rebirth introduced by the mysteries prepared the ground for later religious transformations. What began as foreign cults became part of Rome’s spiritual fabric, offering new ways to understand fate, morality, and immortality. Beneath the surface of official religion, the mysteries gave voice to the private faith of the empire—a faith that sought not merely the favor of the gods, but communion with them. (Mysteries and Fears in Ancient Rome, by Claudio Romano)

Rivalries, Not Missions: The Religious Landscape of the Early Empire

As faiths intertwined and competed, religion itself became a language of identity — a force shaping both private lives and imperial policy. In the cities of the early Roman Empire, faith was not confined to temples or synagogues—it was part of daily life, woven into the language of loyalty, trade, and community.

The rise of Christianity, often portrayed as the inevitable victory of a new faith over an exhausted pagan world, was in fact a far more complex process. For centuries, the empire’s religious life was defined not by conversion but by coexistence. In the crowded marketplaces of belief, Christians, Jews, and followers of countless local cults competed for space, recognition, and survival.

The assumption that early Christianity spread through an organized “mission” belongs to a much later age. The first generations of believers did not move through the empire as formal evangelists but as travelers, merchants, and migrants whose faith took root through contact and circumstance. Their expansion was gradual and often invisible, leaving little trace in material evidence before the late second century.

Christianity’s earliest centers were not in Rome itself but in the eastern provinces—Asia Minor and Syria—where ancient traditions of philosophy, prophecy, and communal worship had already created fertile ground for new religious movements.

In these regions, Jewish communities of the diaspora had long provided a framework for collective worship and moral life, and their synagogues offered a model of association that early Christian groups naturally inherited. Yet the claim that Christianity simply continued a Jewish mission to the Gentiles is misleading.

Judaism’s outreach was largely passive; it welcomed converts but did not seek them. The Christian idea of spreading the faith to all nations emerged only gradually and lacked the institutional form that later centuries would associate with “missionary work.”

Religion in the Roman world was not about belief alone but about participation. People joined associations and cults because they offered honor, healing, protection, or belonging. To be part of a group was to share in its rituals, banquets, and acts of mutual support.

Paganism, Judaism, and Christianity all thrived within this same social fabric. Their rivalries were not wars of ideology but contests of credibility and endurance—each offering its own path to security in a world where divine favor was never certain.

The pattern of early Christian growth therefore reflects not organized conquest but cultural negotiation. Its communities took shape alongside others, sometimes borrowing from them, sometimes opposing them, but always sharing the same urban environment.

Apologies and polemics—so abundant in later writings—served more to define identity within than to win converts from without. What drew adherents was not systematic evangelism but the appeal of belonging to a disciplined, charitable, and hopeful brotherhood amid the instability of empire.

In this sense, the success of Christianity mirrored the success of any social group that met the needs of its members. It offered salvation and community, but also a new kind of solidarity that transcended city and class. Its endurance cannot be traced to one cause or doctrine, but to its ability to compete—quietly yet persistently—in the crowded religious marketplace of the Roman world. (Ancient Religious Rivalries and the Struggle for Success. Christians, Jews, and Others in the Early Roman Empire, by Leif E. Vaage, in Religious Rivalries in the Early Roman Empire and the Rise of Christianity)

Faith, Identity, and Power: Understanding Religion in the Roman Empire

Religion, culture, and power have always been intertwined. In every society, faith shapes identity and social order, defining who belongs and who stands apart. Modern parallels make this clear: in Britain, for instance, Christianity remains a cultural marker even as active belief declines, while Islam—despite millions of British adherents—is often seen as foreign.

Religious affiliation still frames both personal self-understanding and how others perceive an individual. Power, too, flows from these associations; the Church of England’s continued status as the established church ensures its presence in the nation’s governing fabric, even as its influence wanes.

Such connections reveal how religion functions as both symbol and structure. It provides meaning, articulates moral order, and establishes social boundaries. As Clifford Geertz (a famous American anthropologist strongly supporting symbolic anthropology) observed, it is:

“a system of symbols which acts to establish powerful, pervasive and long-lasting moods and motivations.”

Through this lens, religion cannot be separated from culture: it reflects the values by which people live and defines the frameworks of belonging within diverse societies. In a multicultural environment, where belief is one choice among many, religion becomes a key marker of identity, distinguishing individuals and communities alike. Its power originates in the claim to mediate with the divine; whoever controls access to that sphere commands authority in the human one.

In the Roman Empire, these dynamics took a markedly different form. There was no single, unified faith binding the empire together. Every people, tribe, and even city maintained its own traditions, producing a patchwork of practices rather than an orthodoxy. The empire’s “normative” religion existed mainly as a shared language of ritual and symbolism forged by cultural exchange and the practical need for coexistence.

More fundamentally, the very concept of “religion” as a distinct sphere of life did not exist. Divine interaction was expressed through ritual, myth, art, and philosophy—threads interwoven with politics, poetry, and civic duty. Public worship was an act of governance as much as piety; sacrifices, festivals, and temple dedications belonged to the same world as taxation and law.

The Romans made no clear division between sacred and secular, faith and function. What modern thought isolates as “religion” was, for them, a seamless aspect of public and private life. Understanding worship in the Roman world therefore requires setting aside modern assumptions about belief, doctrine, and personal faith. It means seeing how ritual affirmed civic identity, how reverence for the gods reinforced imperial order, and how power, culture, and piety operated as one.

The Ritual Heart of Roman Religion

Roman religion revolved around action rather than belief. Unlike the faiths that would later dominate the Mediterranean world—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—it was not founded upon sacred revelation or divine commandments but upon a set of traditional practices.

These customs, passed down through generations, were designed to maintain harmony between mortals and the gods by securing divine favour through ritual precision. The essence of piety was not orthodoxy but performance: prayer, sacrifice, and offering formed the language of devotion.

Prayer was understood as negotiation rather than confession. A typical invocation began by naming the god, continued by recalling past devotion or gifts, and concluded with the request itself. Praise without petition took the form of hymns, which evolved into both liturgical and literary art.

Offerings complemented these prayers—small cakes, flowers, or incense for everyday rituals, or grander sacrifices of animals in moments of public or personal need. Vows (vota) were central to this exchange: the promise of a gift to the gods upon fulfillment of a request.

At the summit of ritual stood the blood sacrifice. Whether it involved a bird or a bull, each act followed an intricate choreography—libations, chants, and gestures that had to be executed flawlessly. Yet such rites were not reserved for a priestly elite.

Any Roman citizen could offer sacrifice, reflecting a religion open to participation rather than monopolized by clerical authority. Priests were civic administrators as much as custodians of the sacred, their prestige deriving from public duty rather than divine privilege.

Underlying these rituals was a pragmatic understanding of the divine order. The gods were many, their powers vast yet responsive. They could bless or harm, but their goodwill could be earned through proper respect and offerings. Theology remained implicit—Romans acted because their ancestors had done so and because the rituals worked. Religion was, above all, a lived tradition: orthopraxy, not orthodoxy.

Greek influence enriched this framework without altering its foundations. Through myth and philosophy, Romans found new ways to imagine the gods. Poets such as Virgil and Ovid infused epic narrative with divine drama, while thinkers like Cicero debated the nature of the divine, weighing Stoic providence against Epicurean detachment and Academic doubt.

Yet these speculations never replaced ritual; they existed alongside it, part of what scholars have called the “brain-balkanization” of Roman thought—the capacity to hold multiple, even conflicting, understandings without feeling contradiction. A man could doubt the gods in theory and still serve them in office, as Cicero himself did.

Morality, too, remained largely separate from worship. The Romans did not seek divine favour through charity or virtue but through honour and gift-giving. Justice pleased the gods, but it was not a condition of salvation; religion lacked commandments and sacred texts prescribing moral law.

There was no Sermon on the Mount, no promise of eternal reward or punishment to enforce ethical living. Instead, the relationship between humans and gods was reciprocal: honour was given, favour expected. In this world, ritual—not faith, doctrine, or moral perfection—was the true measure of devotion. (Religion in the Roman world, by James Rives)

The Divine Order of State and Soul

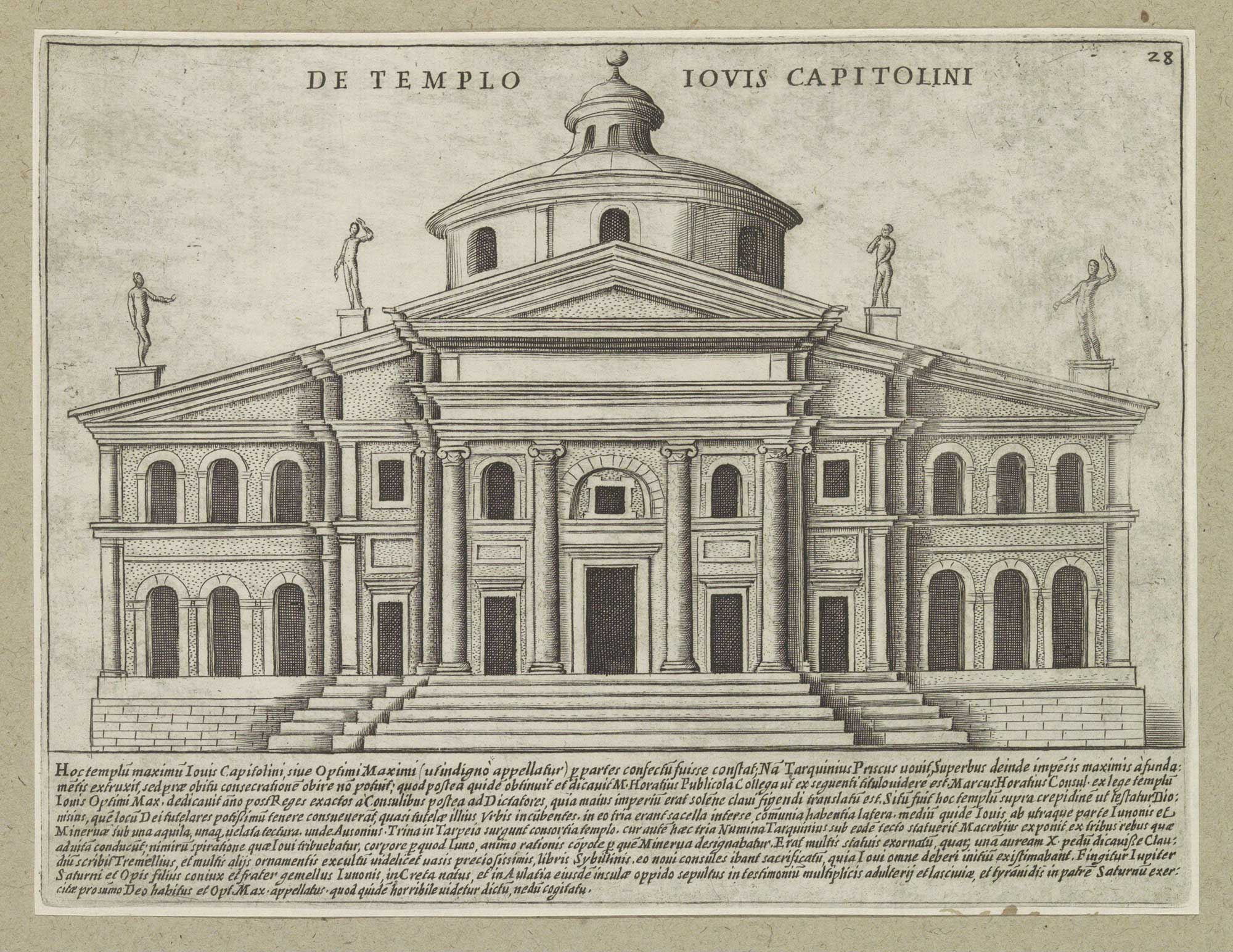

At the heart of Roman religion stood the belief that divine favour sustained the state itself. The gods were guardians of civic harmony, and Jupiter—Optimus Maximus, the Sky-Father—reigned as the embodiment of that sacred balance. His temple on the Capitoline Hill was not merely a sanctuary but the symbolic centre of Rome’s political and moral order.

Religion, for the Romans, was therefore not confined to private conscience; it was a public contract between gods and people, enacted through the precise choreography of ritual. Each prayer, vow, and sacrifice affirmed the pact that bound Rome’s fortune to the divine.

The performance of these rites, rather than the personal belief of their participants, was what mattered most. In the eyes of Jupiter and his fellow deities, correctness of action outweighed inner conviction.

As the empire expanded, this partnership between power and piety reached new forms of expression. Emperors were honoured as living intermediaries between gods and mortals, their genius and spirit enshrined in temples across the provinces.

The imperial cult did not demand worship of the ruler as a god in the modern sense; rather, it affirmed loyalty to the Roman order itself, sanctifying political obedience through divine symbolism. Statues, altars, and festivals celebrated the emperor’s presence as a cosmic principle of unity, echoing Jupiter’s role as protector of the world.

Yet beneath these grand displays of state religion, ordinary Romans maintained their own bonds with the divine. Household shrines to the Lares and Penates received daily offerings; travelers carried amulets; soldiers invoked Mars or Mithras for strength. Personal devotion flourished within the larger system of civic worship, demonstrating that Roman piety was both collective and intimate—a tapestry woven from the shared rituals of empire and the private gestures of the faithful.

In this world, religion was not a doctrine to be professed but a duty to be performed. From the grandeur of Jupiter’s temple to the quiet prayers whispered before a family altar, Roman worship defined the rhythm of both state and soul. (The religions of the Roman Empire, by John Ferguson)

In the end, Roman religion was less a creed than a mirror of the empire itself—vast, diverse, and bound by duty. It united the living and the divine through ceremony, not confession; through shared action, not shared belief. Whether in the shadow of Jupiter’s temple, within the secret chambers of Isis, or before the household altar, every offering affirmed a single truth: that harmony between gods and mortals was both the foundation and the fate of Rome.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: