Rome’s Tastiest Obsession: The Red Mullet and the Price of Prestige

The Roman passion for red mullet drove them to pay fortunes to have this delicacy on their tables.

To dine in style in ancient Rome, you didn’t just need wine and wit—you needed a red mullet. Known for its tender flesh and flamboyant death, this small fish stirred a culinary mania among Rome’s wealthy. Senators squabbled over who could serve the largest specimen, dinner guests watched in rapture as its scales shifted hues, and writers like Seneca rolled their eyes at the madness of it all. The red mullet wasn't just food—it was status, performance, and scandal on a silver plate.

The Romans cherished red mullets so much that they bred them in domestic ponds and trained the fish to come to the surface when a bell rang or upon their owner's call. Quintus Hortensius, a noted Roman orator and senator, preferred to buy his mullets from Puteoli rather than use those from his own ponds at Baculo.

Varro noted his extreme care for these fish, stating:

"He took more pains to keep his mullets from getting hungry than he did for his mules...It would be easier to borrow his mules and carriage than to take a mullet from his fishpond."

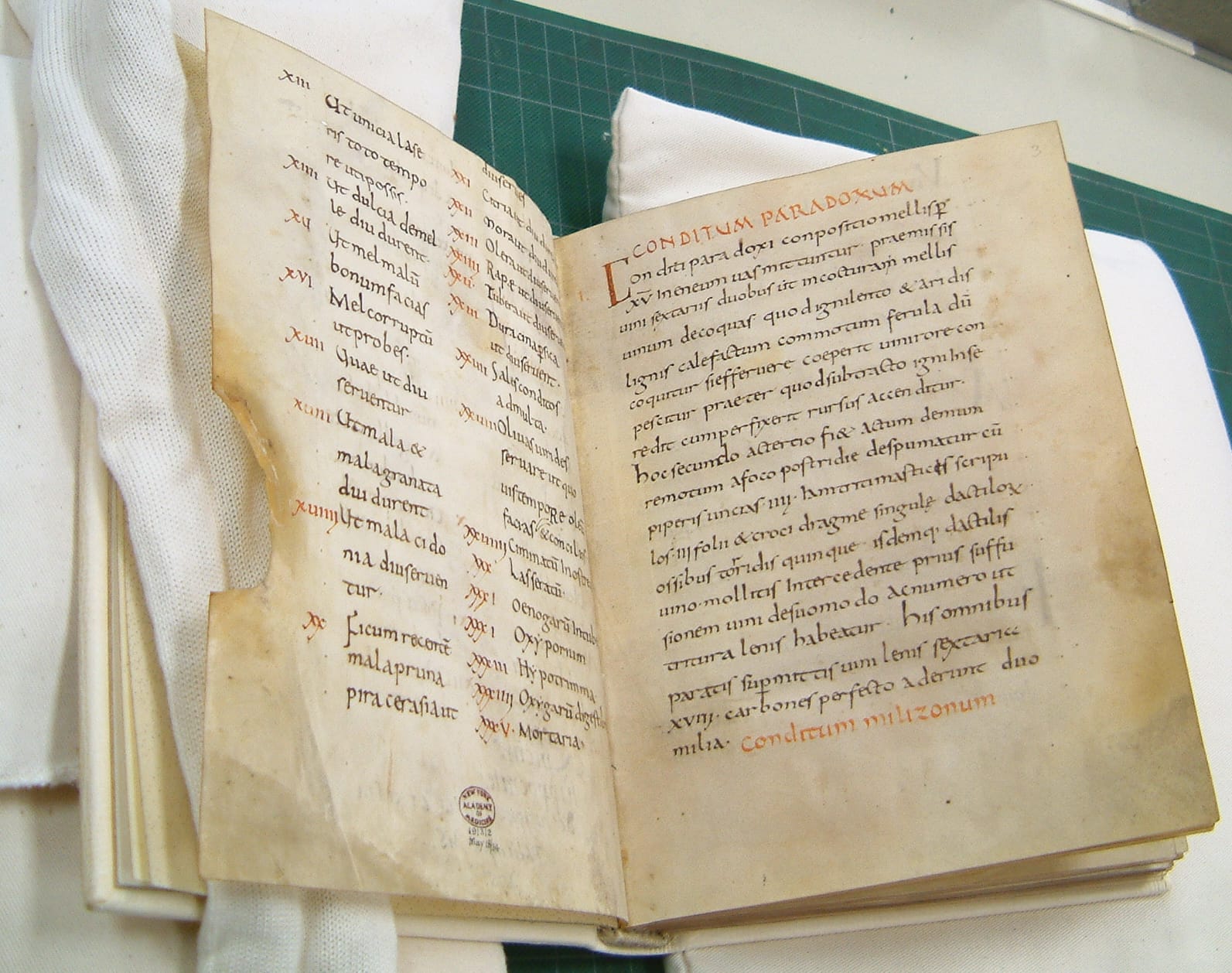

The Red Mullet's journey from the sea to the sumptuous tables of Rome is a story steeped in both culinary tradition and social symbolism. Ancient texts, including writings by Pliny the Elder and the gastronomic scholar Apicius, highlight the fish's esteemed status. These sources reveal not only recipes but also the cultural weight carried by the red mullet in public feasts and private dinners.

A Luxury from the Sea: Fish, Freshness, and Elite Status

In the dining culture of Rome’s elite, fish weren’t just food — they were symbols of taste, wealth, and proximity to the sea. Their freshness mattered above all, which made them both difficult to obtain and immensely valuable. Cicero remarked on how the most refined dinner parties involved not only the best cooks and bakers, but also expert fishermen and hunters — optimis cocis, pistoribus, piscatu, aucupio, venatione, his omnibus exquisitis.

Roman mosaics and wall paintings reflect this culinary prestige: xenia still-lifes from Pompeii show whole fish laid out as offerings for guests, emphasizing not only their appearance but their pristine condition, uncooked and freshly caught.

Even in marine-themed seascapes, the depiction of live fish in vivid detail suggested access to species so desirable they were identifiable on sight — a pictorial boast of what the villa owner could serve at a moment’s notice.

Fishponds (piscinae) became essential status symbols in this world of elite dining. Because transporting fresh fish was both expensive and uncertain, wealthy Romans bypassed the market by building private reservoirs on their estates. These ponds weren’t just practical—they were architectural declarations of taste.

John D’Arms, (Professor of Humanities and professor of classical studies and history at the University of Michigan), citing Horace and Varro, notes that red mullet and shellfish were particularly valued at convivia, where the illusion of sparing no expense delighted dinner guests.

Maria Jaczynowska draws attention to the notorious extravagance of Lucius Licinius Lucullus, whose name became an adjective—lucullanus—synonymous with excessive luxury. After his triumph in 66 BC, Lucullus diverted an entire mountain stream to fill the fishponds of his Neapolitan estate and constructed additional ones near Baiae. Pliny tells us that, after his death, the fish in his ponds alone were worth four million sesterces.

These piscinae were not commercial ventures—they were competitions in refinement. As Jaczynowska argues, displaying one’s wealth through architectural and culinary splendor was central to senatorial identity, and fishponds became the aquatic jewels of that social performance. In this light, dinner parties were no longer just feasts—they were theater, and the fish served were the stars.

Even when Roman writers describe fish in poetic or naturalistic terms, the emphasis often returns to quality, location, and desirability. Apuleius, quoting Ennius’ Latin translation of the Hedyphagetica, compiles a gourmet’s guide to the sea:

“How superior to all is the sea weasel (moray) of Clipea, the 'mice' are at Aenos, the rough oysters are fullest at Abydos.

The scallop is of Mytilene… the sea bream at Brundisium is good… the best littleboar fish is prime at Tarentum… the elops at Surrenti and the glaucus near Cumae… the octopus of Corcyra, the fat skull-fish, the purple fish, the murriculi, the murex, and also the sea urchins are sweet.”

Written originally for a courtly Macedonian or Epirote audience, the passage reads like a fish-lover’s fantasy, but it also reminds us that much of the surviving literature on Roman food reflects elite preferences, not everyday realities. These sources speak of markets only in their most opulent forms — the sellers and buyers of the extraordinary, not the ordinary.

Not all species favored by Roman elites were ideal candidates for life in fishponds. Red mullet (mulli), for example, are naturally solitary and thrive in open, saltwater environments—unlike other fish more suited to the brackish, enclosed conditions of a villa’s piscina.

Yet despite the challenges, their status as one of the most coveted delicacies made them worth the effort. The promise of profit and prestige was enough to tempt even the most impractical attempts at cultivation.

While most ancient sources focus on the elite’s appetite for luxury seafood, a few voices begin to reveal just how distorted the market had become. Pliny the Elder, lamenting the extravagant tastes of the upper class, writes,

“But now a cook is bought for the price of three of these [horses], and fish at the price of three cooks.”

Natural History, IX.31

The absurdity wasn’t lost on satirists either. Juvenal quips that a craving for red mullet could drain a man’s entire purse, while Seneca sets the price of a two-kilogram specimen at an eye-watering 5,000 sesterces. When three especially large mullets sold for a staggering 30,000 sesterces (±110,000 US dollars each), even Emperor Tiberius was alarmed. According to Suetonius, he responded by attempting to regulate prices at the fish market.

The proposed intervention speaks volumes. Fish—once a common food of the Mediterranean—had become so entangled in elite performance and price inflation that access to it was vanishing for ordinary Romans. Price control wasn’t just a reaction to absurd luxury; it was an attempt to reclaim the fish market from complete aristocratic monopoly. (An Examination of the Economic Role of Table Fish in Ancient Rome, by Allyson R. King)

A Dying Beauty: The Price, Performance, and Prestige of the Red Mullet

It wasn’t just the taste of the red mullet that captivated Rome—it was its death. One of the most hauntingly vivid descriptions comes from Seneca, who records the spectacle with a mixture of fascination and revulsion. As the fish gasped its final breaths, it became a canvas of shifting color:

“There is nothing,” you say, “more beautiful than a dying surmullet... first a red, then a pale tint suffuses it... the scales change hue… What a bright kind of blue gleamed right under its brow! Now it is stretching out and going pale and is settling into a uniform hue.”

Seneca, Natural Questions

This morbid fascination—watching a mullet die in a glass jar to confirm its absolute freshness—was more than culinary; it was performative. The fish’s color change became entertainment, a luxury spectacle for those who could afford to turn death into dinner theater.

There is nothing, you say, 'more beautiful than a dying mullet.'

Seneca, Natural Questions (III.18.1,4)

Although mentioned by the Greeks, the mullet didn’t stir particular enthusiasm in early accounts. Archestratus, the gourmet poet, cared more about where the best ones could be found than how they tasted. Romans, however, developed a unique obsession. Cicero wrote to Atticus about elite fishponds where red mullet were hand-fed, while Columella warned that their delicate nature made them almost impossible to keep in captivity:

“It is a very delicate kind of fish and most intolerant of captivity, and so only one or two out of many thousands can on rare occasions endure confinement.”

Despite its abundance, the red mullet, particularly those of notable size, became a status symbol. Pliny describes it as:

“distinguished by a double beard on the lower lip,”

He notes that even when raised in fishponds, it rarely exceeded two pounds (Natural History). But this didn’t stop the Roman elite from paying absurd prices for increasingly larger specimens.

Horace mocked the obsession with a three-pound (±1.36 kilograms) mullet admired only to be sliced into ordinary portions. Martial, never one to miss a jab, noted that anything smaller than two pounds (±0.91 kilograms) wasn’t worth serving—and that even a modest-sized mullet might cost a fortune. He even records someone who sold a slave for 1,200 sesterces, only to spend it all on a single four-pound fish (1.81 kilograms) in his Epigrams.

The fish Tiberius offered at auction weighed four and a half pounds, while Juvenal speaks of a mullet fetching 6,000 sesterces—more than the fisherman himself was worth. During Caligula’s reign, Asinius Celer reportedly paid anywhere between 6,000 and 8,000 sesterces for a single mullet.

As aforementioned, the prices became so outrageous that Suetonius tells us Tiberius eventually considered market regulation after three mullets sold for a combined 30,000 sesterces. The emperor even had a fisherman’s face scraped with the fish for disturbing his retreat in Capri—then ordered the man’s face torn with a crab as well when he sarcastically mentioned having a larger crustacean in reserve.

Even smaller mullets were too expensive for most Romans. Martial joked that a man of modest income shouldn’t marry if he wanted to keep buying mullet. So precious was the fish that guests sometimes wrapped leftovers in a napkin to bring home—half a mullet was a prize in itself.

Though its meat was said to taste like oysters, Pliny also notes the symbolic weight of its appearance. The fish’s shimmering red scales gave it the nickname “shoe mullet,” from the mulleus calceus, the red shoe worn by Roman patricians. Tertullian famously sneered that even a madam from a Carthaginian brothel wore such shoes, mocking the gap between appearance and virtue.

So if the taste didn’t justify the price, and the texture of larger specimens left much to be desired, what exactly were Romans buying?

A red mullet swimming in its natural habitat. Credits: EllenMoran from Getty Images, by Canva

The answer lies in what Seneca and Martial hint at: the act of possessing it, the ability to say you had it, to outbid Apicius or dazzle your guests with the precise moment of death and color transformation. It was spectacle disguised as supper—conspicuous consumption in its most elegant form.

But like all such obsessions, it faded. By the late fourth century AD, the red mullet had been dethroned. Ausonius praises the river perch as the new delight of Roman tables:

“who alone canst vie on equal terms with the rosy mullet”

Mosella, 115–119

Macrobius, reflecting on the old prices paid by Asinius Celer, could only scoff: the age of the mullet had passed.

When Rarity Ruled: The Obsession with Giant Surmullets

The surmullet (Mullus barbatus or Mullus surmuletus) wasn’t prized for taste alone—or even primarily for it. By the late Republic, the fish had evolved from a modest food item into a dazzling object of elite rivalry, where rarity, not flavor, dictated value.

Wealthy Romans began to chase ever-larger specimens, not because they tasted better—in fact, larger ones were considered tougher and less digestible—but because their size made them exceptional. “This seems rather to have been a pure manifestation of luxury,” writes Andrews, “with rarity alone serving as the criterion of value, and quality a negligible factor.”

Some believed that watching the red mullet die in glass vessels, its color changing from red to pale to iridescent hues, added to the experience. Pliny notes the “succession of shades” as the fish faded before the guests’ eyes, while Seneca mocks the practice as grotesquely common at the Roman table:

“A surmullet, even if it is perfectly fresh, is little esteemed unless it is allowed to die before the eyes of your guest... shifting as they struggle in the throes of death in varied shades and hues.”

Natural Questions

Despite efforts, the fish refused to conform to market demands. Attempts to breed oversized surmullets in fishponds failed—Pliny and Columella both mention that the fish resisted captivity and seldom grew beyond its natural size, frustrating the hopes of wealthy speculators. What little success existed was reserved for aristocrats who raised them more as aquatic pets than commercial assets.

By the time of Galen in the late 2nd century AD, the price frenzy had cooled. Galen still acknowledged the red mullet as flavorful but questioned the preference for oversized ones. When asked, a buyer admitted the cost was for the liver and head—two parts Galen personally found overrated in both taste and nutrition.

The surmullet craze eventually came to symbolize the vanity of conspicuous consumption. Andrews compares it to a modern tycoon boasting of the largest goldfish in his aquarium—setting off a wave of imitators and speculative bidding. By the fourth century, Macrobius declared the frenzy over, and Ausonius had already named the perch as the new delight of Roman tables. (The Roman Craze for Surmullets, by Alfred C. Andrews)

The Theatre of Death: Watching the Mullet Die

In Roman dining rooms, the death of a red mullet wasn't hidden in the kitchen—it was center stage. The fish was often brought to the table alive and allowed to expire in front of the guests, usually inside transparent vessels as already mentioned. What captivated the Roman elite was not merely the freshness of the meal, but the vivid, almost hypnotic changes in the mullet’s skin as it died. The spectacle became a kind of table-side performance.

As noted in "Fish: Food from the Waters", hosts were known to serve the mullet in glass bowls or crystal vessels so that diners could observe the fish’s final struggle. Its scales pulsed and shimmered, displaying a spectrum of reds, violets, and silvers that shifted with every spasm.

These color changes were not only morbidly beautiful—they were interpreted as markers of elite taste. Watching a mullet die became a social ritual, a test of refinement.

This practice went beyond culinary pleasure. It was a statement of control: over wealth, over nature, and even over death itself. The mullet, held captive in its transparent tomb, embodied the theatricality of Roman excess. One scholar likened it to “a work of living art,” admired not for what it would taste like, but for the fleeting beauty of its demise.

By staging such moments, Roman hosts didn’t just feed their guests—they awed them. (Fish: Food from the Waters, edited by Harlan Walker)

Priced for Prestige: When a Fish Cost More Than a Slave

For Rome’s upper class, the red mullet was not merely food—it was an edible emblem of wealth. The prices it commanded bordered on the absurd. Martial, always keen to expose vanity through wit, writes of a man who sold a slave just to afford a particularly large specimen:

"You sold a slave to buy a costly mullet for your dinner, Calliodorus…”

Epigrams X

The craze reached a fever pitch under Emperor Tiberius. In one scene described by Seneca, a massive red mullet weighing four and a half pounds was brought before the emperor, who then mockingly put it up for auction.

“I shall be taken entirely by surprise, my friends, if either Apicius or P. Octavius does not buy that mullet.”

As it turned out, P. Octavius paid five thousand sesterces for the fish—outbidding even the notorious gourmand Apicius. It was not simply about eating well. It was about being seen to possess what others could not.

Such prices were not uncommon. A single mullet could cost several times more than the annual wage of an average Roman citizen. Hosting a banquet where several were served could cost as much as a small villa. The fish became an economic spectacle, its value driven not by flavor but by the desire to outshine one’s peers.

Even Galen, Rome’s most respected physician, was baffled by the obsession.

“Prized by men as superior to the rest in flavor… Very many people buy the largest red mullet, which is not as tasty as the smaller ones, nor as easily digested.”

He found their flesh to be dry and slightly bitter. Still, although he disagreed, he did acknowledge the appeal of their liver and head—both considered delicacies and sometimes used in making garum, the fermented fish sauce found in kitchens across the empire.

Taste, nutrition, practicality—none of it mattered. The red mullet’s true flavor, was status.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: