Strabo: Mapping the World of Rome

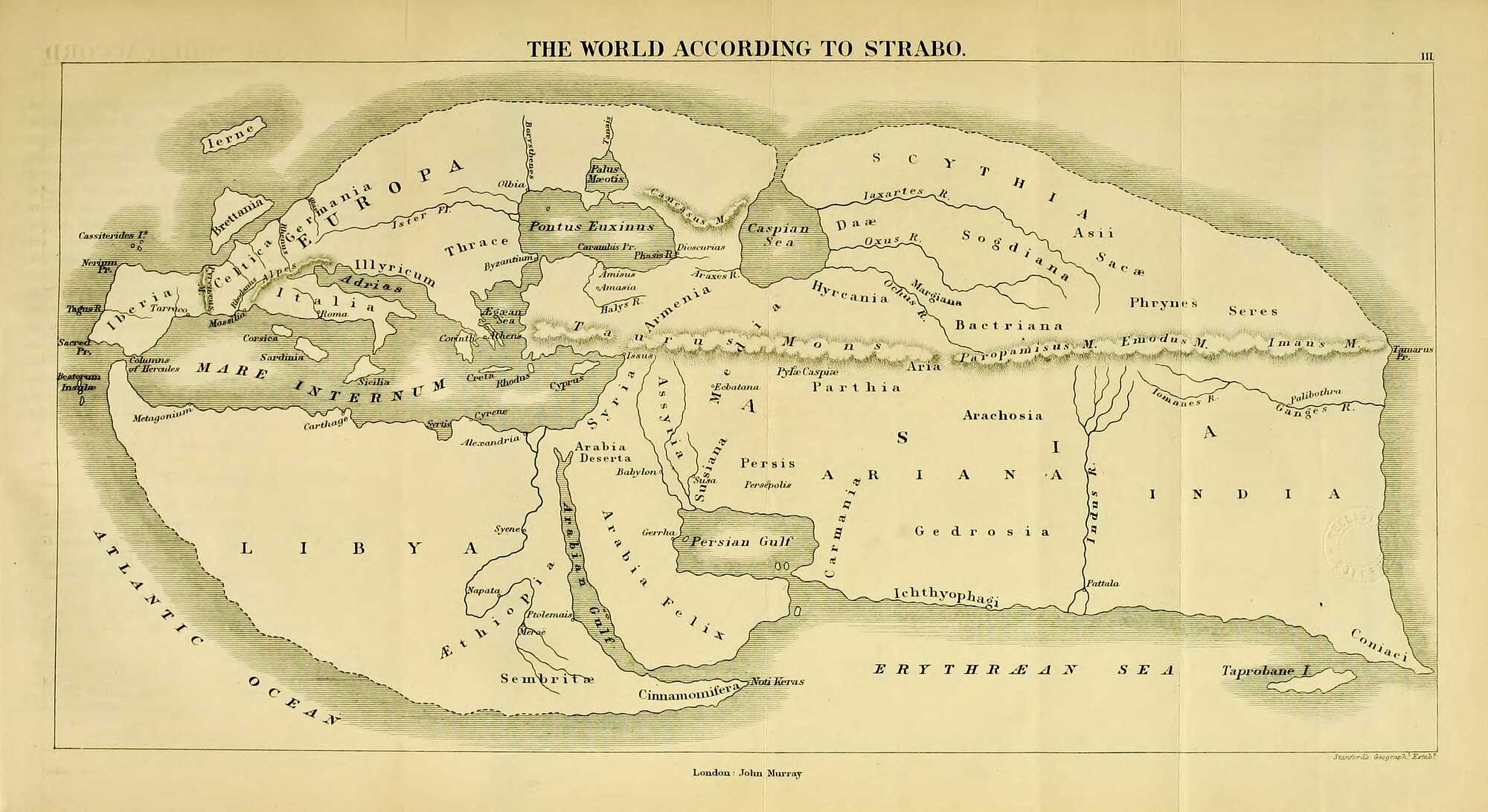

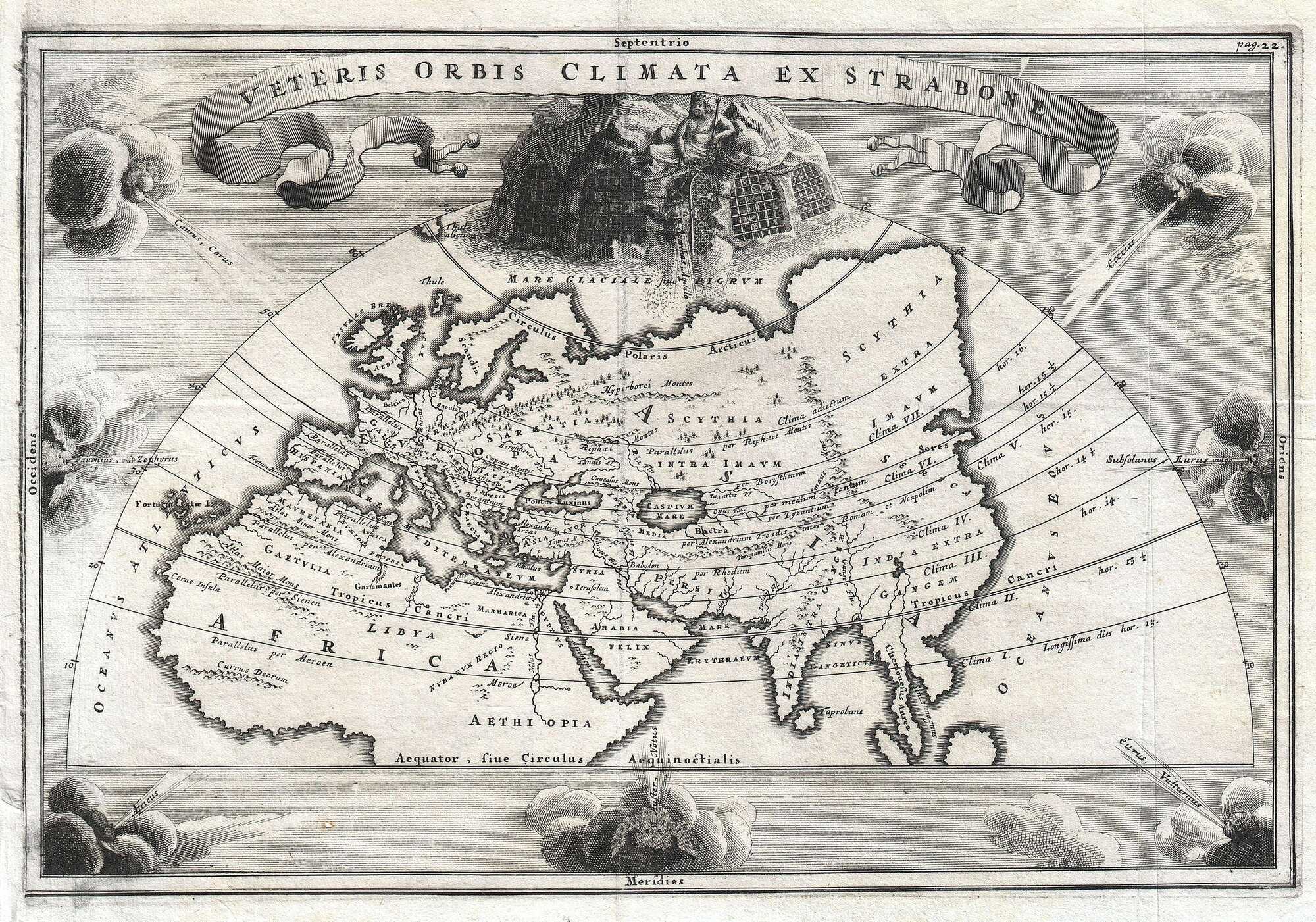

Strabo’s Geography stitched together mountains, rivers, and peoples into a vision of Rome’s dominion. His work, both silent and selective, mapped not just lands but identities, placing cities, cultures, and empire within concentric circles of belonging.

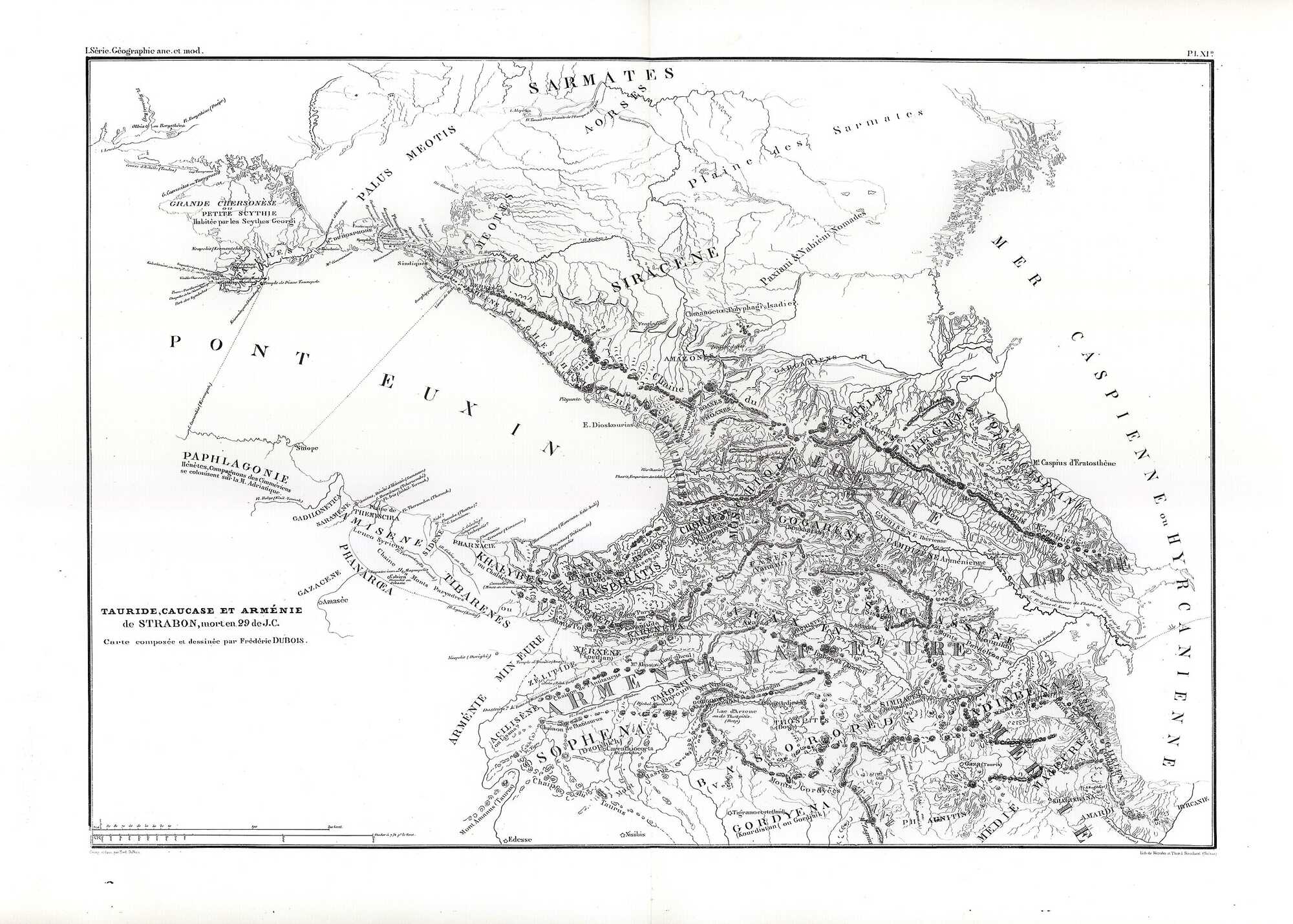

In the quiet of Augustus’ reign, a Greek scholar from distant Pontus set his stylus to wax tablets and began charting the edges of empire. Strabo had walked Roman roads, sailed Roman seas, and listened to stories carried by merchants and soldiers. From these fragments he built a world: the Geographica, seventeen books that stitched together mountains, rivers, and nations into a single vision of Rome’s dominion.

Strabo Between Silence and Presence: The Geographer’s Voice in His Geography

The Problem of Authorial Presence

Ancient geography, like modern geography, wrestled with the issue of the author’s voice. Modern scholars debate whether the writer should erase himself for objectivity or acknowledge his partial standpoint, what some call “situated knowledge” — the idea that “knowledge is always embedded in a particular time and space; it doesn’t see everything from nowhere but rather sees something from somewhere.”

Ancient writers faced similar questions. Ethnographers and historians like Thucydides or Dionysius of Halicarnassus traditionally began by naming themselves and their origins. By contrast, geographical texts were often anonymous, creating the impression of impersonal authority.

Strabo’s Geography falls within this tension. He never names himself, and often prefers the plural “we,” even when recounting personal experiences. Yet his work leaks traces of his identity. The Geography thus raises the question: is the author absent, or is his presence deliberately reshaped?

The Silence Around Strabo

Almost nothing external survives about Strabo. His History, written before the Geography, is preserved only in nineteen fragments, cited by Josephus, Plutarch, and Tertullian. After that, it disappeared.

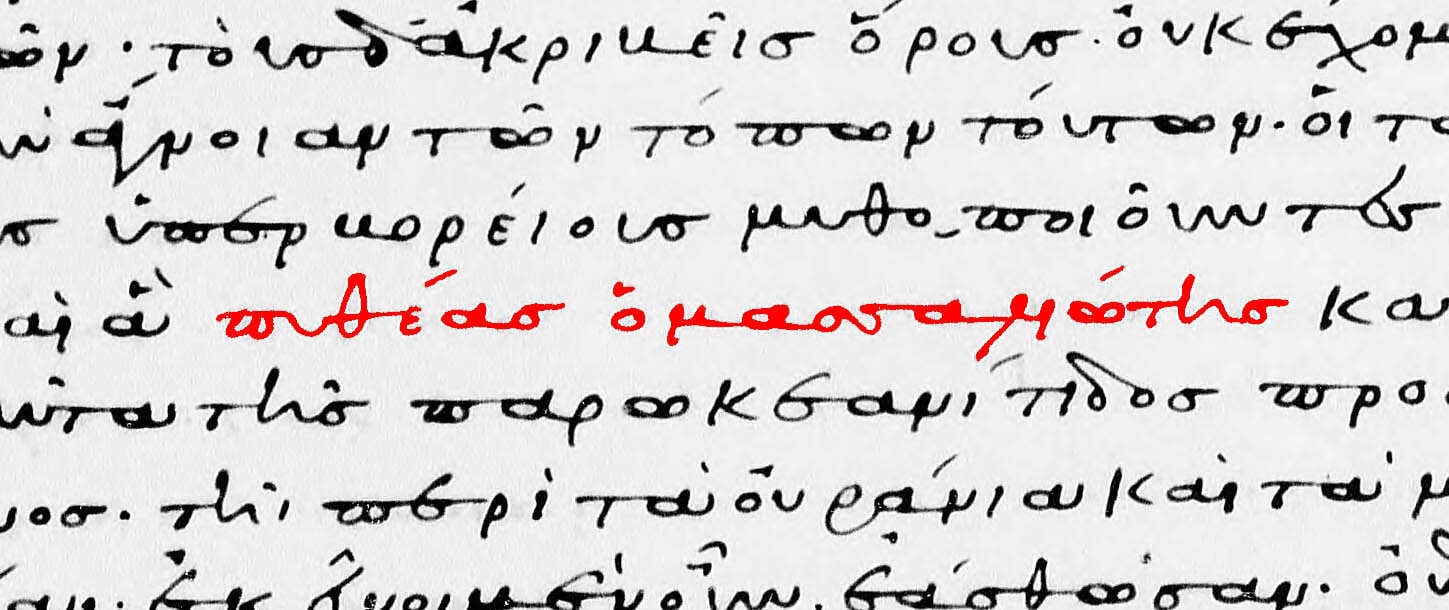

The Geography also languished in obscurity, with almost no references in the first five centuries. Dionysios Periegetes, writing around 120 CE, may have drawn on it, but there are no named citations until much later. Its survival owes everything to the chance sixth-century transfer of papyrus texts to parchment, preserved in part in the Strabo palimpsest.

This scarcity makes reconstructing Strabo’s life difficult. Contradictions in the text itself leave even his basic biography uncertain. For centuries, the Geography was mined as a reference work, stripping it of its authorial dimension. Yet the absence of outside testimony forces us to treat his authorial voice — however scattered — as the main path to understanding him.

What Strabo Reveals of Himself

Though rarely, Strabo does insert autobiographical notes. From these we learn that he was a native of Amaseia in Pontus. His mother’s family was closely connected with the Mithridatic dynasty, producing relatives who served in the royal court. These ties involved Cretan links through mercenary recruitment, later complicated by shifting allegiances when Rome subdued Mithridates.

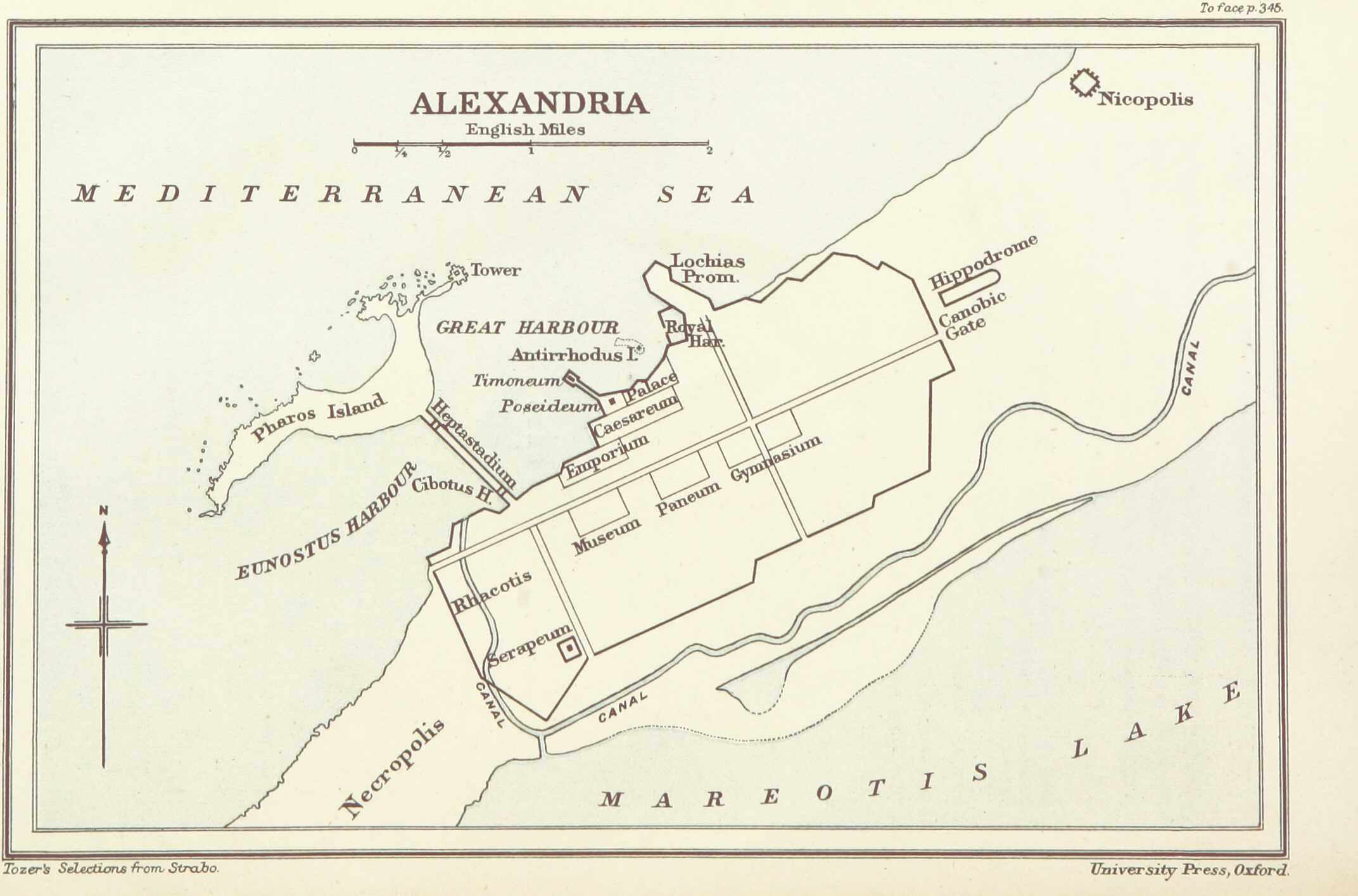

He was educated by Aristodemos of Nysa. He travelled widely: he saw the execution of the bandit Selurus in Rome, the treasures looted from Corinth displayed in a Roman temple, and the narrowing of the Pyramos River in Cilicia. He crossed the Aegean in 29 BCE and accompanied Aelius Gallus up the Nile into Aethiopia in 25/24 BCE. He claimed to have travelled:

“from Armenia to Tyrrhenia, and from the Euxine to the borders of Aethiopia.”

Despite these revelations, Strabo never offers a coherent self-portrait. Information appears only sporadically: details of his family not until Book 10, a fuller account in Book 12, and notes about intellectual friendships scattered throughout. Even when personal, the information serves a broader function — to claim autopsy, first-hand observation, the same authority used by historians like Polybius. Strabo presents himself as one who has seen more of the world than any other geographer.

The Debate Over His Travels and Dates

Modern attempts to reconstruct Strabo’s biography from these scraps lead to uncertainty. Did he visit Athens, or only Corinth? Was he present in Rome in 44 BCE when Servilius Isauricus died, as one ambiguous passage suggests? Some argue he must have lived extraordinarily long, into the reign of Tiberius, if he really saw the elder Isauricus; others prefer to think he met the younger Servilius. But even this is uncertain, as Strabo’s use of “we saw” may not mean literal personal sight, but rather collective knowledge.

His references to “in my time” (καθ’ ἡμᾶς) or “recently” (νεωστί) prove equally elusive. These phrases can refer to spans of decades. Events from the 60s BCE to the 20s CE all qualify as “recent.” Such expressions frustrate biographers but serve another purpose: they place Strabo within an intellectual and historical continuum, rather than pin him to precise dates.

Strabo’s self-positioning emerges most clearly in how he refers to contemporary intellectuals. He often notes that certain philosophers, orators, or historians flourished “in our time.” These remarks occur most often in Books 12–15, centered on Asia Minor and the Hellenized eastern Mediterranean. Here Strabo situates himself within Greek intellectual circles, not simply as a Pontic native or a Roman-connected observer, but as a member of a learned community stretching across the Greek East.

Thus Strabo’s authorial persona has multiple facets:

- A Pontic Greek, rooted in a family with Mithridatic ties.

- A Roman-connected intellectual, friend of Aelius Gallus and visitor of Rome.

- A participant in the Greek scholarly world of Asia Minor.

Geography as Universal History

The choice of style also links Strabo to writers of universal histories such as Polybius and Diodorus. These authors avoided personal self-introductions, often using plural voice, to present a work that encompassed the world. Strabo modeled himself on this tradition. The Geography is thus the spatial counterpart to universal history: a geography of the inhabited world as shaped by Rome.

This framework explains his emphasis on Pompey, Julius Caesar, and Augustus. Pompey especially embodied the Roman idea of world dominion, reaching all three continents. Inscriptions in his triumphal procession listed the nations he had subdued, symbolizing universal conquest. Julius Caesar too had dreamed of encircling the known world with Roman rule. Strabo’s Geography reflects these ambitions, portraying a world in transformation under Roman power.

Strabo’s Relationship to the Roman Empire

Strabo’s tone toward Roman expansion is generally descriptive rather than celebratory. He records Pompey’s reorganization of Asia Minor, the defeat of pirates, and the settlement of colonies, but without the praise found in other sources. Even when recounting the Battle of Actium and the rise of Augustus, his focus lies on how these events altered the shape of the world. His concern is less with Roman politics than with the geographical consequences of Roman victory.

By the time of Tiberius, Strabo still writes in the present tense of Rome’s order, noting campaigns in Germany and the assistance given to earthquake-stricken cities of Asia Minor. His Geography thus spans the Republic’s last decades and the establishment of the Principate, reflecting a world unified, at least conceptually, under Rome.

A Deliberate Impersonality

The absence of a formal preface introducing himself signals Strabo’s deliberate stance. Like the historian Theophylact Simocatta centuries later, he replaces himself with the subject of his work. The opening declares geography to be a theme of philosophy, shifting attention from author to project.

“Geography is in substance an acquaintance with the existing state of the inhabited world, and of the phenomena therein; and of the differences due to countries, nations, and cities, and their peculiarities. It is also the business of a philosopher.”

Yet he is not invisible. Katz (Cindi Katz, a cultural geographer-her full line was: “although it was traditional for the ethnographer to erase himself from the text or to report with omniscient authority, there, of course, could be no ethnography without the ethnographer.”) once remarked, “there could be no ethnography without the ethnographer.”

Likewise, there is no geography without the geographer. Strabo’s scattered self-references — to his travels, his connections, his contemporaries — reveal a presence woven into the very fabric of his universal project. His voice affirms that geography is not impersonal description, but a literary enterprise reflecting the horizons and intellectual affiliations of its author. (In Search of the Author of Strabo’s Geography, by Katherine Clarke, in Journal of Roman Studies)

A Geographer of the Principate

The Geography belongs to the reign of Tiberius. Its references show that the work was written and revised when Augustus’ order had passed into the hands of his successor. Strabo presents the empire as requiring a single leader, a system stabilized by Augustus and perpetuated by Tiberius.

The description of Tiberius as the one man at the helm of Rome’s dominion, aided by Germanicus and Drusus, reflects a political reality in which the Principate was not a temporary solution but the definitive form of government.

Augustus the Architect, Tiberius the Heir

Throughout the Geography, Augustus appears as the founder of cities, the organizer of provinces, and the builder of victory monuments. His triumph at Actium and the foundation of Nikopolis stand as milestones. The empire described by Strabo is shaped by Augustus’ settlements, particularly in Greece and Asia Minor.

Tiberius enters as the custodian of this legacy. He is portrayed not as an innovator but as the ruler who continues Augustus’ structures. The elevation of Cappadocia to a province after the death of King Archelaus in 17 CE is noted as a joint act of Tiberius and the Senate. Earthquake-stricken cities in Asia Minor are shown receiving his aid. In these passages, Tiberius is presented as the guarantor of stability, ensuring that the order Augustus established remained intact.

The Geography of Silence

Strabo’s omissions are as significant as his statements. The Varus disaster of AD 9, which annihilated three Roman legions in Germania, is mentioned, but the details of catastrophe are muted. Instead, the account moves quickly to the later campaigns of Germanicus and the triumphs that followed.

Elsewhere, disturbances and wars are acknowledged only briefly, if at all. By smoothing over defeat and emphasizing eventual success, the Geography aligns with the political tone of the Principate. The text avoids undermining the image of Rome as the master of the inhabited world. This silence does not suggest ignorance but a deliberate shaping of narrative.

The inhabited world is mapped within the framework of Rome’s supremacy. All roads and seas lead back to Rome; every province and people is oriented toward the center of power. Rome becomes both the axis of geography and the guarantor of security.

This is not a neutral ordering of space. The presentation of the oikoumene rests on the assumption that the empire binds it together. Trade routes, military campaigns, and cultural exchanges are described as elements of a world united under Roman rule. Geography itself becomes a reflection of imperial ideology, showing Rome not only as conqueror but as the structure that holds the known world in place.

The Geography is therefore marked by its Tiberian context. It is written during a time when Augustus’ vision had been realized and institutionalized. The empire is presented as stable, continuous, and oriented around one ruler. The silences concerning unrest and the emphasis on order reveal that the work was composed not merely as a compilation of facts, but as a text that embodies the worldview of the Principate. (Strabo, the Tiberian Author: Past, Present and Silence in the Geography, by Sarah Pothecary)

Strabo and the Construction of Ethnicity

Geography as Order

For Strabo, geography was never a neutral description of seas and mountains. It was a representation of the inhabited world, creating order by classifying what belonged together and what stood apart. His Geography was explicitly human geography, where the interaction of peoples, their histories, and their environments carried meaning.

The final aim of such knowledge was political: geography supported the establishment, extension, and preservation of orderly society. By arranging lands and peoples in this way, Strabo also provided the building-blocks of identity.

Strabo’s system of ethnicity rested on dichotomies. He drew lines between civilised and uncivilised, Greeks and barbarians, Romans and non-Romans. These boundaries were not fixed; they depended on situation and context. Ethnicity, in this sense, both included and excluded: it defined the in-group and the out-group.

For Strabo, distinctions could be based on kinship, language, dress, behavior, and above all political organisation. His descriptions, though often derived from written sources, were shaped by his own hand, and the judgements expressed were his own.

The Measure of Culture

Strabo’s anthropology revolved around control and domination. The positive side was self-control, moderation, and political intelligence, revealed in stable governments and a wise use of natural resources. The negative side was extravagance, luxury, lack of communal spirit, and instability.

Successful rule and the ability to maintain power demonstrated aretē, virtue. By these standards, some peoples lived in an ordered and civilised fashion, others remained in disarray.

Greeks and Barbarians

The traditional Greek contrast with barbarians permeates the Geography. The word barbaroi appears in contexts tied to the Persian Wars, to Alexander’s campaigns, and to nomadic Scythians. It could also be applied more loosely to Iberians, Gauls, Thracians, or Tyrrhenians.

Barbarism signified misery, poverty, instability, and savagery — peoples without discipline, often robbers or nomads, unable to form lasting political order. Strabo sometimes chose the stronger word agrioi, “savages.” Yet his usage often carried the tone of a literary topos, inherited from Greek tradition, rather than a rigid system.

From Mountains to Coasts: Stages of Evolution

Civilisation and barbarism were not only opposites but also stages in an evolutionary sequence. After the great flood, survivors first lived in mountains, then moved to lower ground, then to plains, and finally to coasts and islands. Forms of subsistence marked levels of culture: farming, pastoralism, hunting, robbery, fishing, and trade.

Civilisation grew through lawgivers, founders, and conquerors who turned scattered groups into communities. Festivals, religious feasts, and shared meals fostered social bonds. Good government could transform robbers into citizens. Strabo stressed that humans were by nature communal, and civilisation depended on forethought, law, and tradition.

Yet progress was not guaranteed. Luxury and decadence destroyed strength, and cities could fall into ruin. Greece itself offered examples of decline. Ethnic entities changed with migrations, mixing, and shifting borders.

Cities as the Core of Identity

Strabo’s world was a world of cities more than of peoples. The identity of a city lay in both its present and its past: its mention in Homer, its role in famous events, its constitution, monuments, harbours, and artworks, and above all the notable men it produced. A city that was eunomoumenē, well-governed, embodied civic excellence.

Founders and genealogies mattered less to Strabo than historical achievements and civic order. Pride in cities was shaped as much by poetry and memory as by buildings and institutions.

Rome and the Roman Way

Rome itself stood apart. Its size, fora (plural for forums), temples, and roads surpassed all other cities. The Romans, Strabo noted, had first secured necessities before adorning their city, a sign of their wisdom.

“The Romans, after having provided for the necessities of life in a manner befitting the city, adorned it with fora, temples, porticoes, baths, and other works of the kind, so numerous and so costly that the city might justly be called the greatest of all.”

Geography 5.3.7–9

Although Rome’s site was not naturally favored, alliances, expansion, and institutions had transformed it into the capital of a world empire.

Roman conquests spread civilisation to the edges of the known world, building roads and opening routes. Yet ambiguity remained: while Rome encompassed nearly the entire oikoumene, Strabo acknowledged Parthians and Indians beyond its reach. Rome was supreme, but not alone.

Roman identity, too, was layered. One could become Roman by adopting the language, the way of life, and political forms, not only through citizenship. Inside Rome, distinctions of status — senators, equestrians, citizens — defined belonging.

Concentric Circles of Belonging

Strabo’s view of identity resembled concentric circles:

- The widest circle separated civilisation from barbarism.

- Next came provinces, defined by name, history, and administration.

- Within these stood individual cities, proud of their past and achievements.

- Inside this framework, the line ran between Romans and non-Romans.

- Finally, within Rome itself, status distinctions set apart emperor, administrators, knights, and common citizens.

These circles overlapped, showing that identities in the Roman world were multiple and situational.

Strabo himself stood at the intersection of identities: a Greek from Amaseia in Pontus, a participant in Rome’s empire under Augustus and Tiberius, and a scholar of the Hellenistic tradition. His Geography presents a civilised world framed by cities, culture, and Roman order, with uncivilised tribes scattered within and savages confined to the margins. Geography, in his hands, became a means of defining both empire and the peoples who lived within it.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: