How did Emperor Hadrian’s vengeance led to modern Palestine

Hadrian’s suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt reshaped Judaea forever. Jerusalem became Aelia Capitolina, Jews were barred from their holy city, and the province itself was renamed Syria Palaestina—a lasting reminder of how Rome used power and memory to punish rebellion.

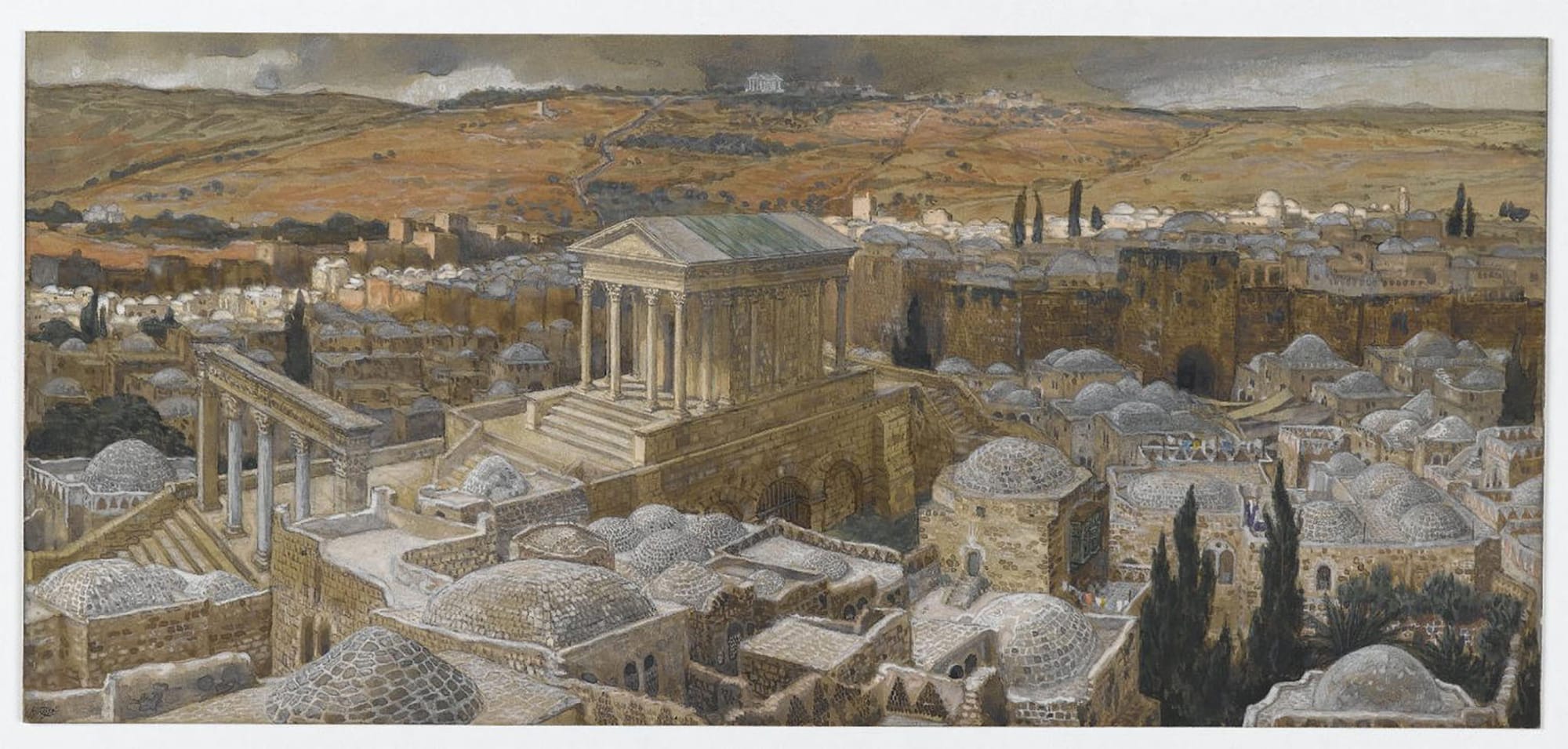

In the second century CE, Emperor Hadrian reshaped the map of the eastern Mediterranean with decisions that still echo today. In the wake of the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–135 CE), Judaea was devastated, its cities leveled, and its people scattered. Out of the ruins rose Aelia Capitolina, a Roman colony built upon Jerusalem, and the province itself was rechristened Syria Palaestina.

These acts were not just punitive measures against rebellion—they were statements of power, identity, and memory. To understand how “Palestine” emerged from Hadrian’s vengeance, we must trace the intersection of Roman imperial strategy, Jewish resistance, and the politics of renaming.

Hadrian’s Journey Through Palestine

In 129/130 CE Hadrian toured Palestine as part of his eastern travels, leaving behind a trail of dedications and coins. He visited Jerusalem, where he resolved to refound it as Aelia Capitolina, and passed through Gaza, which marked the year as the beginning of a new civic era in his honor. Petra adopted the title “Hadriana Petra,” while Gerasa commemorated his presence with a triumphal arch and hosted his imperial guard for the winter — firm evidence that Hadrian himself likely spent time there.

From these cities, richly adorned with Roman-style streets, baths, and temples, the emperor drew inspiration for his plan to impose a Roman identity on Jerusalem. By mid-130, he continued southward into Egypt, leaving behind both monuments of favor and the seeds of unrest that would soon ignite the Bar Kokhba revolt. (Hadrian in Palestine, 129/130 A. D., by William F. Stinespring)

Yet the goodwill Hadrian encountered in places like Gaza, Petra, and Gerasa did not extend to Jerusalem. His decision to remake the city as Aelia Capitolina and impose new laws on its people would soon transform admiration into resistance, leading directly into the crisis that shook Judaea.

Crisis in Judaea: The Roman View of the Bar Kokhba Revolt

When Hadrian visited Judaea in 130 CE on his way to Egypt, the province appeared calm. Imperial coinage even celebrated his adventus as a joyful event. No one in his entourage could have predicted that within a few years, this seemingly quiet province would erupt into the devastating Bar Kokhba revolt, proclaimed by coins bearing slogans such as “Freedom of Israel” and “For the Freedom of Jerusalem.” The conflict turned into one of the bloodiest and most consequential wars of Hadrian’s reign.

Scholars still debate its causes, scope, and consequences, but we will emphasize how Rome itself viewed the revolt. To the imperial government, this was not a minor local disturbance but a major crisis that threatened Roman prestige and demanded unprecedented measures. Cassius Dio, the only Roman historian to describe the conflict (albeit preserved in a later epitome by Xiphilinus), stressed its magnitude:

“At first the Romans took no account of them…

Soon, however, all Judaea had been stirred up, and the Jews everywhere … were gathering together … the whole earth, one might almost say, was being stirred up over the matter.

Then, indeed, Hadrian sent against them his best generals.

Foremost among these was Julius Severus, who was dispatched from Britain, where he was governor, against the Jews.”

According to Dio, fifty strongholds and 985 villages were destroyed, and some 580,000 Jews were killed—though Roman losses were also immense. Hadrian himself, in a letter to the Senate, broke with the traditional opening formula:

“If you and your children are in good health, it is well; I and the legions are in good health”,

reflecting the severe strain on his forces.

The appointment of Sextus Julius Severus was a telling sign. At the time he was governor of Britain, one of the empire’s top military posts with three legions under his command. To transfer him from such a prestigious role to Judaea, a province normally of lesser importance, could only mean an emergency of the highest order. After the war, Severus was restored to his rank by being sent to govern Syria, confirming that his deployment to Judaea was extraordinary.

Other measures further illustrate the crisis. Marines from the fleet at Misenum were transferred into the legions—a move requiring them to be granted Roman citizenship, something rarely done except in dire circumstances. Conscription, highly unpopular in Italy and increasingly rare in the High Empire, was reintroduced to fill losses. Epigraphic evidence records recruitment drives in Central Italy and even the Alpine provinces. The disappearance of Legio XXII Deiotariana from records may also be tied to its annihilation during the revolt.

Hadrian mobilized not only the Judaean legions (X Fretensis and likely either II Traiana or XXII Deiotariana) but also vexillationes from across the empire. Up to twelve or thirteen legions were involved at some stage—a massive deployment given Judaea’s small size. The revolt was not confined to Judaea proper; evidence of its spread includes the arch erected for Hadrian at Tel Shalem, near Scythopolis, and the involvement of the governors of Arabia and Syria.

Rome regarded this as a war comparable to the great crises of the past, such as the Pannonian revolt of 6 CE or the Teutoburg disaster of 9 CE. The Bar Kokhba war, like those earlier catastrophes, revealed the vulnerabilities of imperial power. Even if Rome overestimated the threat, its reaction—the scale of mobilization, the heavy casualties, the extraordinary military transfers—underscores that the revolt left a deep scar on Hadrian’s reign and Roman self-confidence.

Roman Generals, Triumphs, and the Wider War

The early triumphs of Bar Kokhba’s forces and their grip over Judaea proper forced Hadrian to act decisively. Cassius Dio notes that the emperor dispatched “his best generals” against the Jews—plural, not singular. For centuries, this was overlooked, with focus placed almost exclusively on Sextus Julius Severus, transferred from Britain in a rare move signaling crisis. Yet inscriptions make clear that Severus was not alone.

The honors tell the story. In the early Principate, the ornamenta triumphalia had replaced Republican triumphs as the highest recognition of victory. Hadrian was notably sparing in bestowing them; campaigns in Britain, Mauretania, and Dacia had ended without generals so rewarded. That restraint makes the aftermath of the Bar Kokhba revolt striking. Julius Severus was decorated “ob res in Iudaea prospere gestas,” but he shared this honor with others.

C. Quinctius Certus Publicius Marcellus, governor of Syria, left his province to fight across the border, bringing part of the Syrian army into the campaign. Inscriptions from Aquileia confirm he too received the ornamenta triumphalia, suggesting his role in securing victory was decisive. Even more telling is the case of T. Haterius Nepos, governor of Arabia.

Documents and decorations alike show his direct involvement: the legion III Cyrenaica fought in the war, and evidence from the Babatha archive indicates that fighting spilled into Arabia, forcing Jewish families there either to join the rebels or to flee as refugees. Nepos also received the ornamenta, marking him as one of Hadrian’s “best generals.”

With Syria and Arabia drawn in, the war clearly exceeded Judaea’s borders. From Rome’s perspective, this was no localized revolt but a regional upheaval echoing the great crises of the early empire. Hadrian himself, usually indifferent to military display, now broke with habit: he accepted the acclamation Imperator II, embedding it in his titulature. Only then could his generals’ victories be recognized with the highest military distinction. This was the first time since Trajan’s Dacian Wars that multiple commanders were simultaneously honored.

The message was unmistakable. By bestowing the ornamenta triumphalia on Severus, Marcellus, and Nepos, Hadrian acknowledged that the Bar Kokhba revolt demanded extraordinary measures, vast manpower, and the cooperation of Rome’s leading provincial armies. What had begun as a Jewish bid for “the freedom of Israel” became, in Roman eyes, one of the most dangerous challenges their empire had faced in the second century.

After Hadrian’s forces crushed the Bar Kokhba revolt, a monumental arch was erected near Tel Shalem — likely by decree of the Senate and People of Rome — to commemorate the victory. The sheer size of the inscription underlines how seriously the Empire regarded the conflict.

In its aftermath, Hadrian also took the unprecedented step of erasing “Judaea” from the map, renaming the province Syria Palaestina — a punishment aimed at stripping the Jewish people of their ancestral identity.

Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Palestine’s West Bank, from NASA, International Space Station, CC BY-NC 2.0

The crushing of the Bar Kokhba revolt marked one of the darkest episodes of Hadrian’s reign. His measures went far beyond military victory: Jerusalem was rebuilt as Aelia Capitolina, its Jewish inhabitants expelled and banned on pain of death, and the province itself was stripped of its ancient name. By renaming Judaea as Syria Palaestina, Hadrian sought not only to erase the memory of rebellion but to sever the bond between a people and their land. ("The Bar Kokhba revolt: the Roman point of view" by Werner Eck)

The renaming was unique in Roman history. Provinces had been divided, reorganized, and occasionally renamed after geographical features, but never before had the identity of a province been deliberately rewritten as punishment. In doing so, Hadrian transformed a local revolt into a lasting chapter of imperial memory. The very word Palestina, first imposed as an instrument of domination, would endure through centuries of history, long after the empire itself had faded.

Hadrian’s actions in Palestine reveal the double edge of Roman power. Through monuments, laws, and names, Rome could reshape landscapes and identities—but only at immense human cost. The arch at Tel Shalem, the ruins of Aelia Capitolina, and the echo of a lost Judaea all stand as reminders that empires rule not only by armies, but by memory.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: