Pliny the Elder: Scholar, Soldier, and Witness to Disaster

Pliny himself claims that he perused about 2,000 volumes and gathered 20,000 noteworthy facts from 100 authors

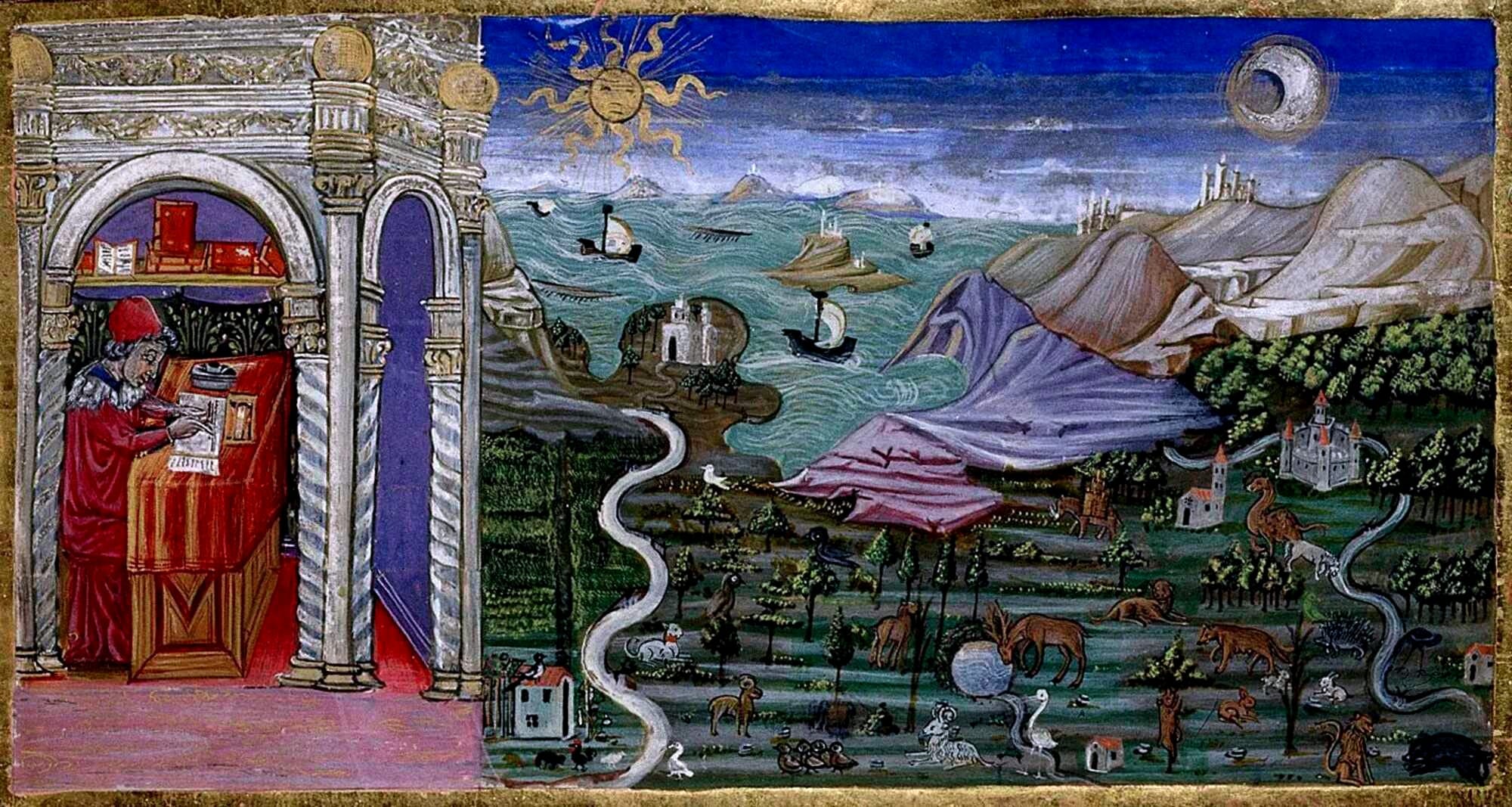

Few figures from antiquity embody the spirit of Roman inquiry and ambition as vividly as Pliny the Elder. A military officer, administrator, and prolific writer, Pliny dedicated his life to collecting and organizing knowledge, culminating in his Natural History—an encyclopaedic attempt to document the world in its entirety.

His career placed him at the heart of the imperial court, where he navigated political, economic, and scientific spheres, yet it was his unwavering curiosity that ultimately led to his death during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. Beyond his better-known achievements, Pliny’s life offers insight into the interplay between power, scholarship, and duty in the Roman world.

A Scholar Shaped by Empire and Duty

Pliny the Elder, Gaius Plinius Secundus, was born in late AD 23 or early AD 24 during the reign of Tiberius, a period marked by political instability, military unrest, and power struggles within the imperial system. His birthplace, Novum Comum (modern-day Como) in northern Italy, was a town of mixed population that had undergone several waves of colonization.

Originally reorganized in 89 BCE by Pompeius Strabo, it later received an influx of settlers under Julius Caesar, who, in 59 BCE, reestablished it under the Lex Vatinia, adding five thousand colonists and renaming it Novum Comum. There is no surviving record of Pliny’s parents, but his father’s name suggests a local Italian lineage rather than aristocratic Roman ancestry.

More significant than his origins, however, was the wealth and social standing of his family, which belonged to the municipal governing class.

A pile of ancient Roman coins. Credits: TheoRivierenlaan from pixabay, by Canva

This background allowed Pliny to enter the equestrian order (ordo equester), a social rank open to Roman citizens of free birth, good character, and a minimum wealth of 400,000 sesterces. Membership in this order determined his career path, granting him access to both administrative and military opportunities.

A Life Documented in Text and Archaeology

Pliny was deeply invested in his status and public service, an attitude reflected in both his writings and the material culture of his time. The archaeological remains of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabiae, and Oplontis, buried under Vesuvius' eruption in AD 79, offer a vivid depiction of first-century Roman urban life—a world Pliny knew well. His Natural History, alongside his nephew Pliny the Younger’s Letters, provides commentary on Roman society, daily life, and moral values.

The cities impacted by Vesuvius reveal notable differences in economic status and lifestyle:

- Pompeii functioned primarily as a commercial center, with public buildings reflecting its mercantile nature. Private residences, though comfortable and aesthetically refined, were generally not excessively ostentatious, as seen in the relative scarcity of imported luxury materials like colored marble and exotic woods.

- Herculaneum, by contrast, was home to a wealthier elite, alongside artisans and fishermen. The architecture and decorative elements indicate a higher concentration of affluent residents compared to Pompeii.

Pliny’s observations on society, commerce, and governance provide an important literary complement to the material evidence from these cities, bridging the gap between textual history and archaeological findings.

Author, Observer, and Intellectual Conservator

In his profile of “Pliny the Elder”, Paul T. Keyser presents a portrait of a man not only immersed in the practicalities of Roman public life but also devoted to a monumental task: the preservation of human knowledge. Pliny emerges here not simply as a Roman scholar, but as a systematic compiler of intellectual tradition, motivated by a desire to document, preserve, and transmit everything that was worth knowing from the ancient world.

What makes Pliny’s Natural History exceptional, according to Keyser, is that it is not narrowly scientific, but rather a comprehensive cultural artifact. It embodies the Roman capacity for synthesis: bringing together Greek, Egyptian, and Roman knowledge, combining practical instruction with historical anecdote, myth, and moral reflection. This work contains 37 books and is built on the foundation of over 2,000 volumes consulted from approximately 100 authors—a remarkable scholarly feat.

"I have included in thirty-six books 20,000 topics, all worthy of attention, (for, as Domitius Piso says, we ought to make not merely books, but valuable collections,) gained by the perusal of about 2000 volumes, of which a few only are in the hands of the studious, on account of the obscurity of the subjects, procured by the careful perusal of 100 select authors; and to these I have made considerable additions of things, which were either not known to my predecessors, or which have been lately discovered.

Nor can I doubt but that there still remain many things which I have omitted; for I am a mere mortal, and one that has many occupations."

Pliny The Elder

He was acutely aware of the scope of his undertaking. He explicitly states that his work was “not composed for literary reputation,” but to be useful. This guiding principle makes the Natural History stand out not only as a record of ancient science and technology, but as a manual of life, designed for administrators, farmers, physicians, artists, and the curious layperson.

Keyser underlines Pliny’s role as a custodian of tradition, noting that many of the sources he drew upon have since been lost. His meticulous citations of sources throughout the Natural History serve both as a scholarly apparatus and as a testament to the fragility of cultural memory.

Without Pliny, vast swaths of classical knowledge—especially Greek writings on botany, zoology, metallurgy, and medicine—might have vanished completely.

Plate from "Flora, seu de florum cultura", by Giovanni Battista Ferrari. Credits: Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0

While Pliny’s encyclopaedic method lacks modern scientific rigor, Keyser reminds us that it must be evaluated within its context. For Pliny, to study nature was not to master it through theory or experimentation, but to bear witness to its marvels and preserve the accumulated wisdom of others. His curiosity was wide-ranging but grounded in Roman practicality, aimed at utility over abstraction.

Keyser also notes that Pliny’s writing style and methodology reflect his deeply Roman sense of duty. The act of compiling knowledge was, in itself, an ethical endeavor: a way to serve both the empire and future generations. His nephew, Pliny the Younger, affirmed this in a letter, describing the Natural History as a mirror of Nature’s own variety and richness.

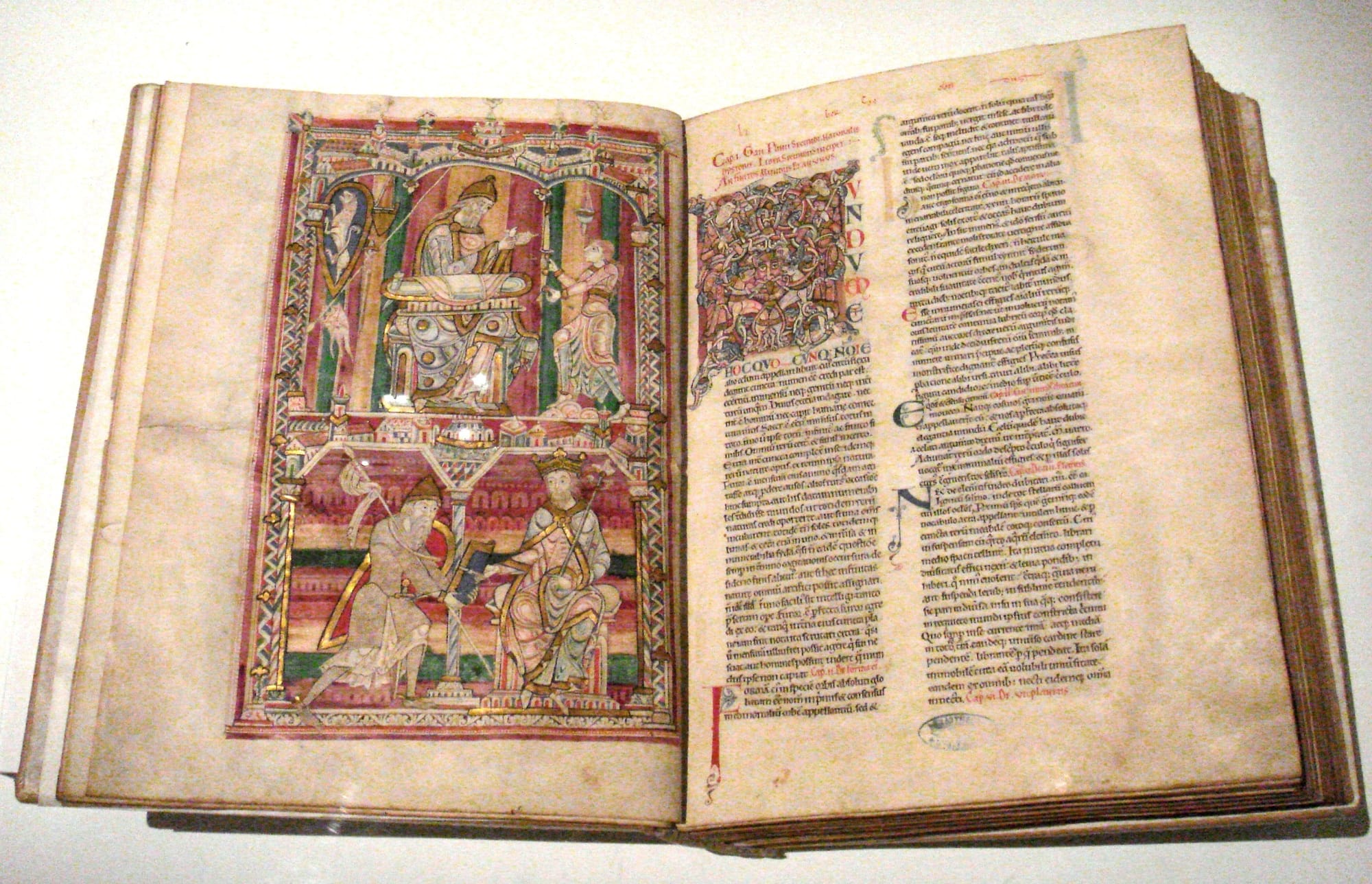

Finally, he highlights the enduring intellectual legacy of Pliny’s work. The Natural History became a cornerstone of medieval and early Renaissance learning, especially in the Latin West. For centuries, it was regarded not merely as a source, but as a model—a comprehensive framework for organizing human understanding of the natural and cultural world.

Even today, while modern science has moved far beyond Pliny’s cosmology and methods, his work remains an invaluable witness to ancient thought, and a reflection of one Roman’s extraordinary effort to capture the totality of life and knowledge in words.

A Life Devoted to the Higher Purpose of Knowledge

Pliny possessed a temperament so deeply inclined toward contemplation and purpose that bodily needs—let alone pleasures—seemed to hold little relevance for him. His way of resting from official duties was not through leisure but through a change of intellectual labor.

Much of his night was dedicated to study; even his meals became occasions for learning, with his amanuensis reading aloud to him as he ate. To preserve his focus, he traveled by chariot instead of walking, using the time to listen and reflect without interruption.

His notes and scholarly annotations were of such value that Lartius Lutinius offered him a substantial sum for them, but instead of selling them, Pliny bequeathed this vast intellectual trove to his beloved and distinguished nephew. His interest spanned all areas of Nature and Art, and nothing was beneath his attention.

In the field of the Fine Arts, his writings—particularly Books 34, 35, and 36 of the Natural History—stand out for their precision, judgment, and depth of knowledge, surviving the cultural collapse that followed the fall of the Roman Empire and preserving a wealth of classical insight.

Pliny’s pursuit of knowledge was inseparable from his humanity and scientific curiosity, traits that ultimately led to his death and made him one of history’s most memorable martyrs to science. His final moments—during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79—are tenderly and vividly recounted by his nephew, Pliny the Younger, in a letter to Tacitus, a passage regarded as one of the most elegant epistles in Roman literature.

Pliny’s body was found three days after his death and buried at Misenum, facing the fleet he had left behind in his quest to observe and understand a natural phenomenon. As a fitting tribute to his life and mind, his nephew offers a sentiment that remains a powerful reflection of Pliny’s legacy:

“I consider those blessed to whom the gods have granted the ability either to do things worth writing about or to write things worth reading; but the most blessed of all are those who can do both.”

Pliny the Younger

“The fortunate man, in my opinion, is he to whom the gods have granted the power either to do something which is worth recording or to write what is worth reading, and most fortunate of all is the man who can do both. Such a man was my uncle…” Pliny the Younger, Letter 6.16

A possible representation of Pliny the Elder, with Mount Vesuvius in the background. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

Only an intense love of nature could have driven a man so fully immersed in public responsibilities to seize every spare moment to assemble what his nephew called “a digest of the scattered rays of natural knowledge.” The study of nature was not a fashionable interest among Romans, and the materials for his monumental work had to be laboriously extracted from Greek authors of many schools, each bearing conflicting ideas.

His effort resulted in 160 densely written volumes of abstracts, each demanding great perseverance and discernment. Although the authors Pliny drew upon often presented contradictory theories, he proved adept at distilling useful knowledge from opinion, even if he sometimes adopted questionable hypotheses as facts.

In his time, there was no established method to verify information, and his sources carried the authority of ancient wisdom. The era of careful, evidence-based criticism could only arise after such an enormous foundation of recorded observation had been laid—and Pliny was the tireless collector who made that foundation possible.

Even when these ancient sources proposed explanations that we now recognize as incorrect—such as mysterious “occult causes” in place of rational science—Pliny’s documentation of them remains significant. Even the mistakes belong to the history of natural inquiry, and his account preserves them as valuable evidence of humanity’s evolving understanding of the natural world. His contribution lies not merely in what he got right, but in gathering the materials out of which future knowledge could grow. (Pliny's Natural history. In thirty-seven books, by Philemon Holland)

Pliny in Rome: A City of Luxury and Contrasts

Internal evidence from Natural History suggests that Pliny the Elder arrived in Rome during the reign of Caligula (AD 37–41), likely in the early 30s. His experiences in the capital, including attending the betrothal dinner of Lollia Paulina, left a lasting impression, particularly regarding the city's excesses. His vivid account of her extravagant jewelry reflects both his keen observational skills and his moral disdain:

"...she was covered with emeralds and pearls which caught the light all over her head, hair, ears, neck, and fingers: these adornments were worth 40,000,000 sesterces!"

Pliny’s indignation was further fueled by the knowledge that these jewels were not gifts but had been acquired through spoils from the provinces, reinforcing his criticism of luxury funded by imperial conquest.

By Pliny’s time, Rome had become a city of extremes. The opulence of Nero’s Golden House (Domus Aurea) and the lavish residences of the elite on the Palatine Hill stood in stark contrast to the overcrowded and dangerous tenement blocks (insulae) where the poor lived. These fragile structures, later described by Juvenal, were precariously stacked “like a house of cards,” with fires being a constant hazard.

Within this diverse environment, Pliny found much to interest him, immersing himself in literature, the arts, philosophy, science, and oratory. His formal education began under Pomponius Secundus, a renowned soldier and tragic poet, whom he later honored by writing his biography. He referred to this work as a “munus debitum”—a duty owed to a friend—potentially as a means to secure patronage and professional advancement.

As was customary for men of his status, Pliny received training in rhetoric, which significantly influenced his literary style. However, this rhetorical approach led to frequent criticism of his writing, particularly for its dense and sometimes elaborate structure.

Scholar and Servant of the State

Pliny, managed to balance public service with intellectual pursuits, demonstrating that scholarship and state duties were not mutually exclusive. His Natural History reflects his political views, which reveal an acceptance of the imperial system as essential to Rome’s stability.

He expresses gratitude for the security provided by the Pax Romana, portraying Italy as both the ruler and the second mother of the world.

“For now that I have completed my survey of Nature's works, it is right that I should make a critical assessment of her products, as well of the lands that produce them.

This, then, I declare: in the whole world, wherever the vault of heaven turns, there is no land so well adorned with all that wins Nature's crown as Italy, the ruler and second mother of the world, with her men and women, her generals and soldiers, her slaves, her pre-eminence in arts and crafts, her wealth of brilliant talent, and, again, her geographical position and her healthy, temperate climate, the easy access which she offers to all other peoples, her shores with their many harbours, and the kindly winds that blow upon her.

All these benefits accrue to her from her situation - for the land juts out in the direction that is most advantageous, midway between the East and the West - and from her abundant supply of water, her healthy forests, her mountains with their passes, her harmless wild creatures, her fertile soil and her rich pastures”

His close ties to the Flavian dynasty are evident in the tone of the preface to the work, which is addressed to the emperor. As a trusted member of Vespasian’s advisory council, Pliny had direct access to the emperor, further reinforcing his role within the imperial administration. (Pliny the Elder on Science and Technology, by John F. Healy)

The Roots of Pliny’s Thought

Pliny the Elder’s worldview, as expressed in Naturalis Historia, is deeply rooted in classical philosophy, particularly Stoicism, though his work is more encyclopaedic than analytical. He envisioned the universe (mundus) as divine, eternal, and governed by rational principles, rejecting the atomist theories of Democritus, Epicurus, and Lucretius, which posited an infinite and perishable world governed by chance.

Instead, Pliny aligned with the Stoic belief in a providential, ordered cosmos, where nature itself was a sacred, self-contained entity rather than a creation of an external deity. This pantheistic view positioned nature as both a divine force and the ultimate source of life, framing the natural world as something to be studied, understood, and respected.

Despite this reverence for nature’s divine power, Pliny’s perspective remained anthropocentric, with humanity as the central subject of his work. He described the Earth (Terra) as providing abundantly for human needs, yet he also acknowledged its destructive power—a duality that suggests a balanced but pragmatic approach to mankind’s place in the natural world.

His writing reflects concern over human exploitation of natural resources, portraying excessive mining and deforestation as disruptions of nature’s will. While he valued scientific inquiry, he remained skeptical of speculative knowledge, particularly magic and divination, which he condemned as attempts to control forces beyond human understanding.

Pliny’s intellectual outlook was shaped by Roman pragmatism, Stoic cosmology, and the encyclopedic tradition. He saw knowledge as a tool for civilization, not as a purely theoretical pursuit, reinforcing the belief that intellectual endeavors should serve both the state and society. His work, though influenced by philosophical traditions, ultimately reflects a deeply Roman worldview—practical, hierarchical, and committed to the idea that nature exists to be observed, not mastered. (The Thought of Pliny the Elder, by Mary Beagon)

Creation of "Natural History"

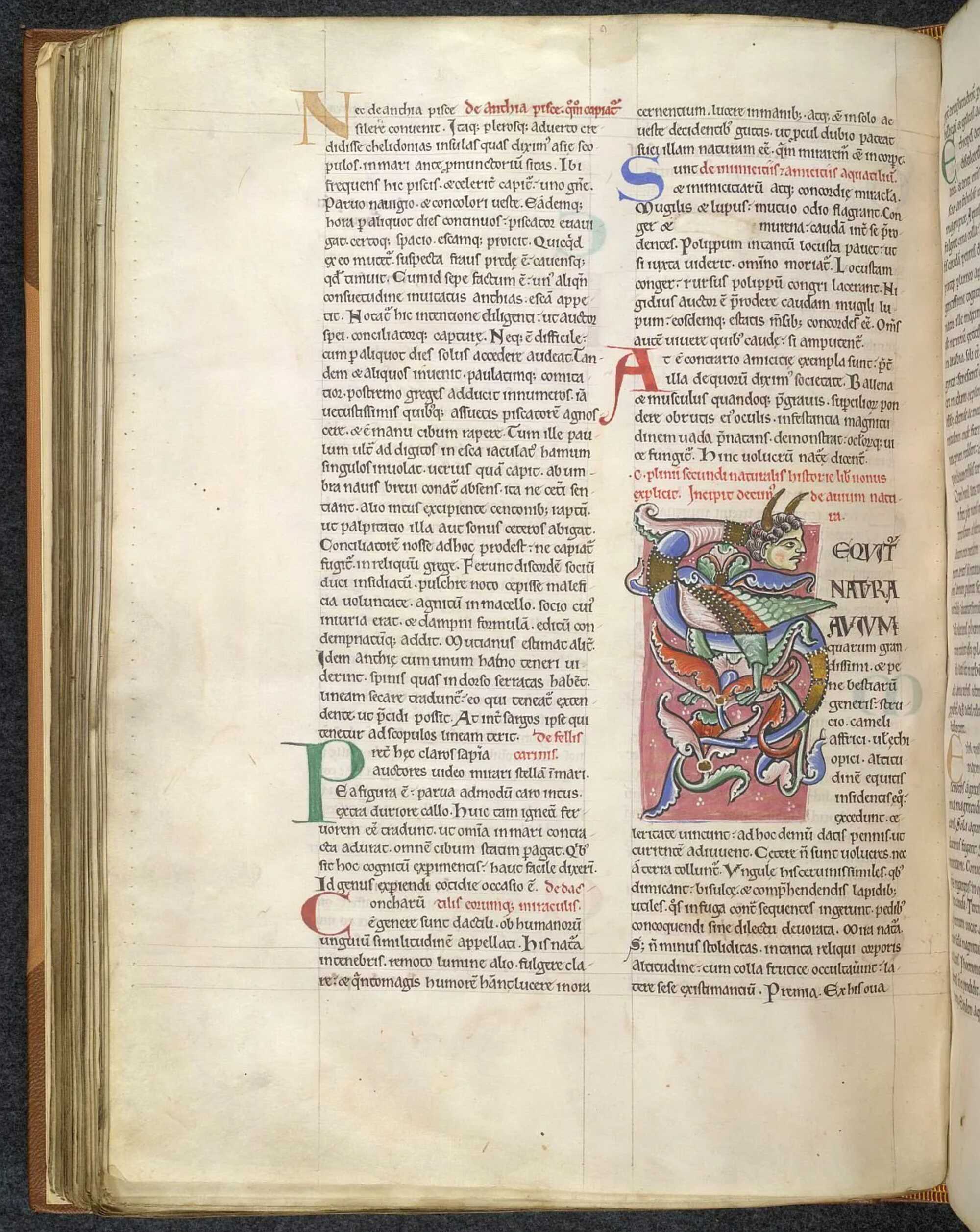

Pliny's "Natural History" is an extensive collection of knowledge that covers a vast array of subjects including astronomy, anthropology, geography, botany, horticulture, farming, zoology, medicine, chemistry, minerology, and art. Comprising 37 volumes, the work was an attempt to document all human knowledge of the natural world in Pliny's time. Drawing from over 100 sources, including his own observations and the work of predecessors, Pliny aimed to provide a critical and comprehensive resource for the Roman public.

Pliny's "Natural History" may be considered the first Western encyclopedia but defining it as such requires understanding that the concept of an encyclopedia has evolved significantly. While modern readers might recognize it as an encyclopedia, this would not necessarily align with the expectations or recognition of its earliest audiences.

The work itself has had a considerable influence on how we interpret and engage with historical texts. Over centuries, it has been a critical reference in various fields, from medicine to zoology, informing scholars and serving as a cornerstone for the development of numerous disciplines.

Although its direct utility for contemporary practitioners may have diminished, its value to antiquarians and classicists remains substantial, providing a window into ancient knowledge and practices. The enduring scholarly reliance on Pliny's work illustrates the complex ways in which historical texts continue to shape modern academic disciplines, even as the nature of these texts and their interpretations evolve over time.

Pliny the Elder's "Natural History" begins with a dedication to Emperor Titus, offering a preview of the extensive contents within the 37-book series. The initial volume delves into cosmology, touching upon the universe, celestial bodies, and fundamental elements. It is followed by a detailed geographic exploration of the Earth and its varied inhabitants. The subsequent book shifts focus to humanity and technological advancements.

“…written for the masses, for the farmers and workers, and to interest people in their leisure time.”

The compendium then examines animals both terrestrial and aquatic, with separate discussions dedicated to birds and insects. Most of the volumes center on botany, discussing trees, plants, flowers, and fruits, extending into their agricultural practices and medicinal uses. Pliny also explores other medicinal resources derived from animals.

The final sections are devoted to minerals and metals, including their applications in painting and the arts, culminating in one of the earliest comprehensive accounts of art history.

Louis Ducis’ The Invention of Painting, as imagined by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History. Public domain

In the second book of "Natural History", Pliny the Elder embraces the traditional Greek astronomical theories, acknowledging the Earth's spherical shape and its implications on phenomena like eclipses, day and night cycles, sunrises, and sunsets.

He identifies the planets known during the classical era: "Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, the sun, Venus, Mercury, and the moon." Pliny's descriptions, particularly of the sun and moon, are imbued with a mythological perspective, often personifying these celestial bodies in line with Roman and Greek traditions. He describes the sun with profound reverence: "[the Sun] lends his light … to the rest of the stars, is splendid, supreme and sees and hears everything."

Pliny wants his readers to know that his book is well researched, covers a wide range of topics, and is up to date. He writes:

“I have included in 36 books 20,000 topics… acquired by the study of about 2,000 volumes… gathered by the careful examination of 100 select authors; and to these I have made considerable additions of things, which were either not known to my predecessors, or which have been lately discovered.

Pliny authored his expansive work "Naturalis Historia" not for profit but as a scholarly endeavor. In his era, long before the advent of the printing press, each book had to be manually transcribed by scribes, making the production of books labor-intensive and costly.

Although Pliny might have commissioned a few initial copies with possible financial backing from the emperor, subsequent copies were made by those who hired scribes to painstakingly replicate the text, which contains over a million words. Modern scholars put the number of pieces of information at 37,000.

Playful Irony and Imperial Address in Pliny’s Natural History

The preface to Pliny the Elder’s Natural History presents itself as a seemingly straightforward introduction, yet on closer inspection, it reveals a layered and playful complexity that both frames and challenges the monumental work it precedes.

Written in the form of an epistolary dedication to Titus, the preface blends humorous self-deprecation, literary allusion, and subtle political negotiation, serving at once as a defense of Pliny’s earlier writings, a guide to the Natural History's content and structure, and a carefully constructed rhetorical address to its imperial reader.

Epistolary prefaces had precedent in Hellenistic science writing and Roman technical literature, and Pliny follows this tradition, yet with distinct innovation. His preface acts both as a proem to the entire work and as a cover letter to Book 1, which contains a detailed table of contents. From the outset, Pliny subverts expectations.

Though the first words—libros naturalis historiae—plainly announce the title and genre, his subsequent tone is deliberately at odds with the gravity of the work. He downplays its seriousness, calling it nugae ("trifles"), and frames it as a sort of 'votive offering' to Titus, filled with curious facts salvaged from obscure and specialized sources.

“THIS treatise on Natural History, a novel work in Roman literature, which I have just completed, I have taken the liberty to dedicate to you, most gracious Emperor, an appellation peculiarly suitable to you, while, on account of his age, that of great is more appropriate to your Father;

For still thou ne'er wouldst quite despise the trifles that I write;"

Yet, Pliny’s modesty is laced with irony. He claims that Natural History avoids the literary flourishes of dialogue, dramatic events, and digression, but as critics have noted, the work itself is filled with rich historical anecdotes and detailed descriptions.

Similarly puzzling is Pliny’s characterization of his material—life itself—as sterilis (barren), a claim that contrasts starkly with the encyclopedic richness of his volumes and his frequent use of fertility metaphors to describe the act of literary production. These paradoxes generate a tone that is at once self-effacing and self-conscious, positioning Pliny as a curator of knowledge whose seriousness is masked by feigned levity.

A central puzzle of the preface is its depiction of the addressee, Titus. While some scholars, have argued that there is a disjunction between the tone of the preface and its imperial recipient—accusing Pliny of filling the dedication with fictions and absurdities—others see the choice of Titus as both deliberate and meaningful.

Titus, as co-ruler of the empire and a man with known intellectual interests and remarkable memory, becomes a representative figure for the totalizing scope of the encyclopedic project. His visit to the Temple of Venus at Paphos, as recorded by Tacitus, marks him as a seeker of antiquities, a curious and cultivated figure who might well appreciate Pliny’s undertaking.

To further draw Titus into the world of the text, Pliny employs a surprising model: the poet Catullus. This choice frames the preface with a tone of light-hearted wit, alluding to poems that evoke friendship, pleasure, and literary play. Titus is addressed as iucundissime, echoing Catullus’ language to his companion Calvus, and Pliny even reworks a Catullan line to suit a more casual, friendly atmosphere. By doing so, Pliny recasts the imperial addressee not simply as an emperor, but as a literary peer, someone familiar with both military life and poetic refinement.

This dual portrayal—Titus as both soldier and aesthete—allows Pliny to align himself with the emperor, not through flattery, but through shared experiences and tastes. He introduces the military term conterraneus (used here with clear reference to camp slang) to further this alignment, emphasizing the bond between encyclopedist, poet, and ruler. Pliny even invites Titus into a linguistic alliance, suggesting that they are both engaged in a struggle to validate and refine Latin usage—a subtle defense of Pliny’s own style against critics.

Pliny’s ironic tone continues as he amplifies the contrast between his supposed nugae and the massive intellectual enterprise he undertakes. His citation of Catullus not only roots the preface in northern Italian identity (both authors being from that region), but also repositions the Natural History as a playful yet serious offering—something akin to a banquet among friends, rather than a coldly didactic text.

"if I may be allowed to shelter myself under the example of Catullus, my fellow-countryman, a military term, which you well understand".

Ultimately, the preface becomes a performance of humility and intellectual charm, designed to reshape the reader’s expectations of both the work and its addressee. Through irony, literary allusion, and rhetorical agility, Pliny redefines Titus from an imperial authority to a kindred spirit, and he reframes his encyclopedia not as a stiff monument of knowledge, but as a living, generous, and human offering—a thesaurus or templis dicata filled with the votive gifts of a curious and diligent mind.

In this way, the prefatory letter is more than a literary nicety. It is a complex rhetorical strategy, presenting the Natural History as both humble and monumental, serious and playful, authoritative and familiar. Pliny sets the stage not only for the reader’s engagement with nature and knowledge, but for a subtle reimagining of the relationship between knowledge, power, and authorship in the Roman world. (Pliny and the encyclopaedic addressee, by Ruth Morello)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: