Nero Unmasked: The Fire, the Fame, and the Fury of Rome’s Most Infamous Ruler (Part 1)

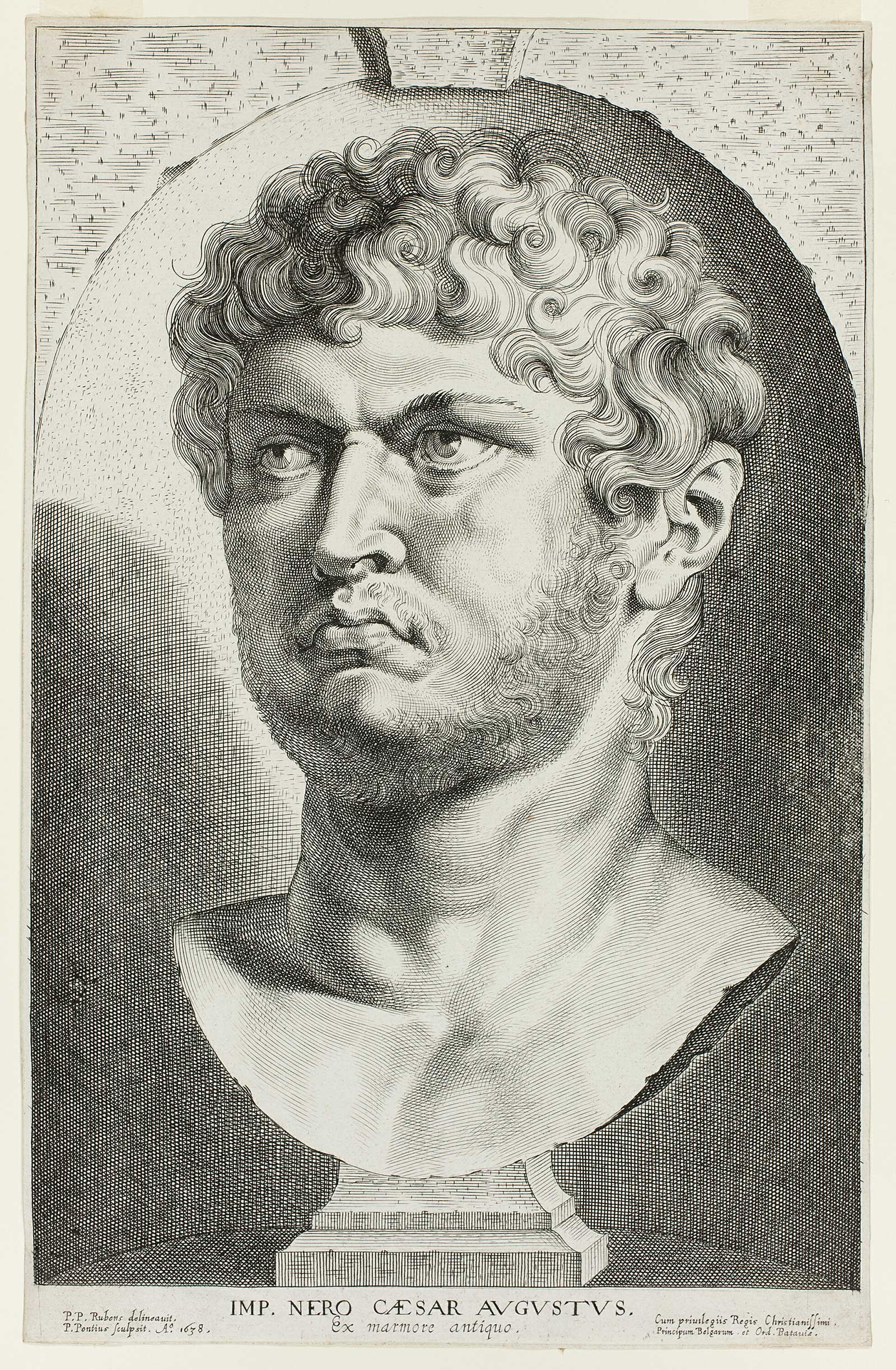

Nero’s legend was forged as much by writers as by deeds. Between art and atrocity, he cast himself as performer-emperor, rebuilt Rome in spectacle and stone, and left a trail of verses, scandals, and lampoons—until the line between ruler and stage all but vanished.

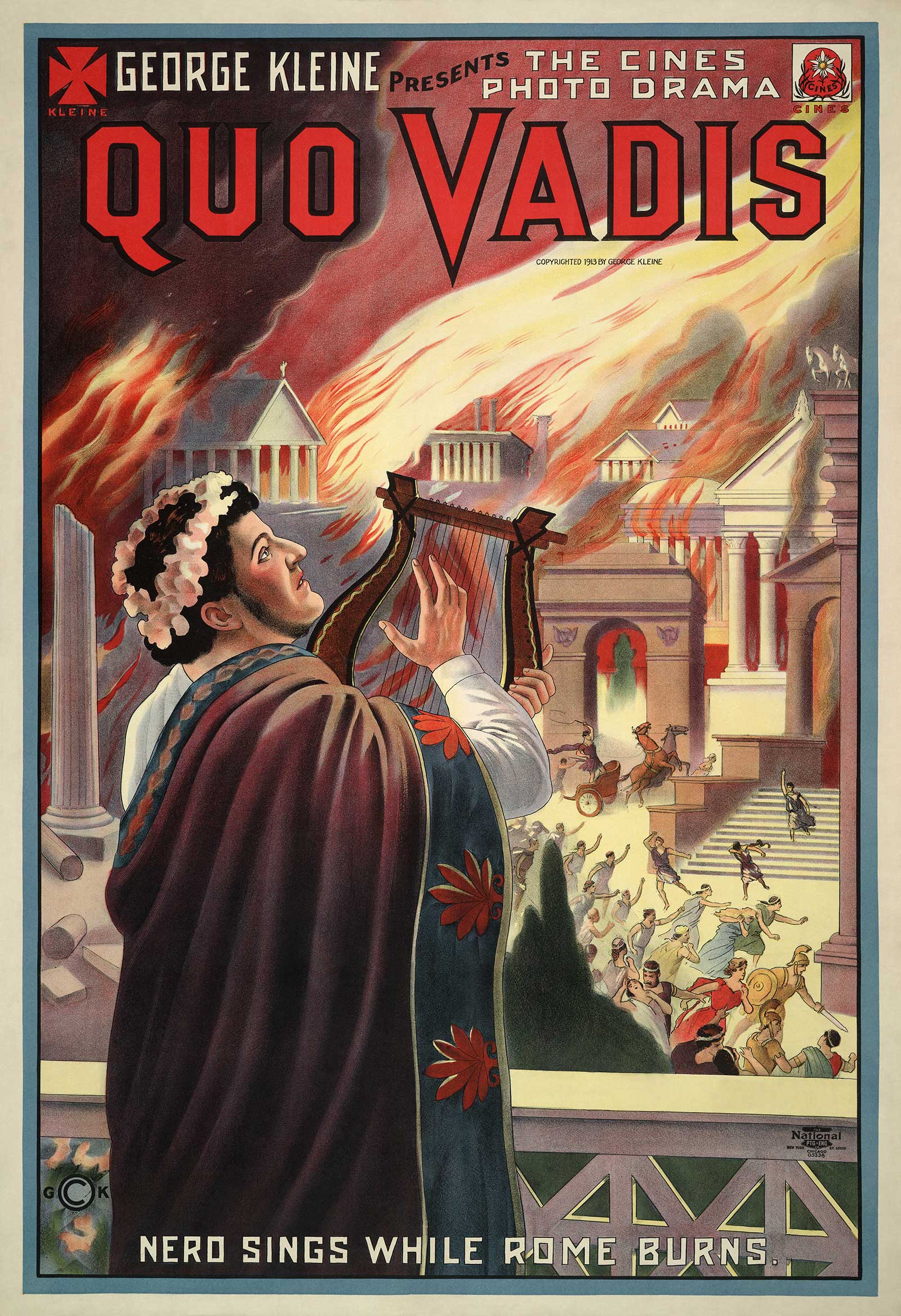

In the flickering glow of Rome’s burning skyline, one name endures in infamy—Nero. To some, he was a monster who murdered his mother, wife, and rivals; to others, a misunderstood artist trapped inside an emperor’s crown.

Between melody and madness, cruelty and creativity, Nero’s reign was a spectacle unlike any other in Roman history. He rebuilt the capital in marble and gold, performed before awestruck crowds, and ruled with a theatrical flair that blurred the line between empire and stage. Yet behind the music lay the echoes of screams, conspiracies, and a dynasty’s ruin.

Choose your Nero myth

The image of Nero that comes down to us depends on which myth one chooses to believe. To some, he was a ruler deeply entwined with literature — the most literary of emperors, whose personality inspired creative production. To others, he cast a suffocating shadow over Roman letters, forcing writers to seek refuge in coded expression and veiled critique.

In either case, Nero stands as a constant presence in the background of all literary creation of his time. The reason we even speak of “Neronian literature,” as we do of Augustan literature, lies partly in the luck of textual survival and partly in the magnetism of certain emperors. While other reigns — Claudius, Tiberius, Caligula — are not granted literary labels, Nero’s age, vibrant with controversy and creativity, endures in the cultural imagination.

Seneca’s tragedies, for instance, may have been written earlier, during his exile under Claudius, yet they fit so naturally with the artistic and introspective tone of Nero’s Rome that they are inevitably folded into the Neronian canon. Periodization itself becomes a form of characterization, a way of breaking up the vast continuum of culture into manageable chapters.

Though we often speak of Nero’s accession as a rupture, in reality his reign carried deep continuities from Claudius. Early hopes for renewal are visible in Seneca’s Apocolocyntosis — a biting “pumpkinification” of Claudius — and in the Eclogues of Calpurnius Siculus, which hailed a new Golden Age under a radiant Apollo-like prince.

Our portrait of Nero is filtered through the eyes of Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio — historians whose agendas colored their narratives. Their hostility toward the last Julio-Claudian has shaped his reputation for centuries. The Nero they describe — the debauched ruler who “fiddled while Rome burned,” slept with countless partners, and even with his own mother (“motherf***er” being the ultimate Roman slur) — is, in many ways, a creation of Flavian propaganda.

The regime that followed Nero needed to define itself against him, and thus the emperor’s eccentric attempts to reinvent Augustan ideals were recast as monstrous excesses. Yet glimpses of another Nero surface here and there: the competent administrator, the dutiful performer of religious rites, and the victor of eastern campaigns.

Still, Dio and his later Byzantine epitomators preferred spectacle to balance. They portrayed Nero not as a political ruler but as “an exhibitionist, a Roman curiosity.” When later Christian writers inherited this image, they amplified it into the portrait of a satanic tyrant.

Before this monstrous figure emerged, however, there was the promising young emperor of the quinquennium Neronis — the “five good years” often praised even by his detractors. Nero, only sixteen when he became emperor, was initially guided by his formidable mother Agrippina, his tutor Seneca, and the praetorian prefect Burrus.

These men managed the administration while Nero indulged his artistic leanings — singing, composing, racing horses, and performing music, as Seneca’s Apocolocyntosis and Calpurnius’ pastoral poetry suggest. Suetonius even notes that the young emperor’s early virtues were

“duty to family, generosity, mercy, and affability”,

Seneca’s treatises On Clemency and On Anger were likely written as moral instruction, offering the prince a mirror for ideal conduct.

Lacking military training, Nero found his calling in the arts. Suetonius begins his catalogue of the emperor’s vices not with cruelty but with music — his devotion to the citharode Terpnus, who taught him to sing and accompany himself on the lyre.

His hunger for admiration led him to Greece, where he believed that only the cultivated Greeks could truly appreciate his talent. To secure his triumph in every contest, he commanded that all six great Greek games — Olympian, Nemean, Isthmian, Pythian, Actian, and Heraian — be held in the same year.

He won them all, returning to Italy as a self-styled victor, an imperator of art. Dio remarks with scorn:

“But he crossed over into Greece, not at all as Flamininus or Mummius or as Agrippa and Augustus, his ancestors, had done, but for the purpose of driving chariots, playing the lyre, making proclamations, and acting in tragedies.

Rome, it seems, was not enough for him”.

Nero’s admiration for Greece was not universally admired at home. Romans had long regarded their Greek neighbors with a blend of respect and condescension. Virgil, in the Aeneid, had Anchises instruct the Romans to “rule the nations,” leaving the arts to others. Nero refused to accept this division. He sang, painted, sculpted, and saw himself as an heir to Hellenic culture.

His lineage partly explains this: his grandfather Germanicus had translated Greek poetry, and Agrippina the Younger had written memoirs of her family’s misfortunes. Martial would later salute Nero as a poeta doctus, a “learned poet”. The emperor’s passion was shared by many in his circle — men like Lucan, Persius, and the anonymous author of Laus Pisonis — revealing a court steeped in art and performance.

Nero’s philhellenism reflected a broader cultural transformation. His reign stood at the threshold of the Graeco-Roman world and foreshadowed the Second Sophistic. His buildings — the Baths, the Gymnasium, and above all the Domus Aurea — embodied this synthesis.

These architectural projects, often interpreted as symbols of excess, can also be seen as expressions of a new conception of leisure (otium) and civic life. Far from being merely decadent, they were manifestations of a Hellenizing future already taking shape in Rome.

Unlike Augustus or Claudius, Nero left little in the way of oratory. Tacitus laments that he relied on Seneca as his speechwriter rather than composing his own. Suetonius claims that Seneca deliberately kept him from the genre to maintain control. The emperor’s eulogy for Claudius reportedly provoked laughter, and he preferred to send letters to the Senate rather than address it in person.

He even avoided speaking to his guards, fearing it might strain his voice. The only speech scholars consider his own is the one delivered at Corinth in 67 CE, when he granted tax exemption and autonomy to Achaia — pronounced in Greek, a language befitting his self-image as a Hellenistic benefactor.

His real passion was poetry. Suetonius describes how he composed verses with pleasure and skill:

“He was instructed, when a boy, in the rudiments of almost all the liberal sciences; but his mother diverted him from the study of philosophy, as unsuited to one destined to be an emperor; and his preceptor, Seneca discouraged him from reading the ancient orators, that he might longer secure his devotion to himself.

Therefore, having a turn for poetry, he composed verses both with pleasure and ease; nor did he, as some think, publish those of other writers as his own.

Several little pocketbooks and loose sheets have come into my possession, which contain some well-known verses in his own hand, and written in such a manner, that it was very evident, from the blotting and interlining, that they had not been transcribed from a copy, nor dictated by another, but were written by the composer of them.”

Suetonius, Nero 52

Tacitus offers a more cynical portrait, describing the emperor’s literary soirées:

“Nero affected also a zeal for poetry and gathered a group of associates with some faculty for versification but not such as to have yet attracted remark.

These, after dining, sat with him, devising a connection for the lines they had brought from home or invented on the spot, and eking out the phrases suggested, for better or worse, by their master; the method being obvious even from the general cast of the poems, which run without energy or inspiration and lack unity of style.”

Tacitus, Annals 14.16

Among those around Nero, Lucan stands out — both for his brilliance and his tragic end. His uncle Seneca and the arbiter of taste, Petronius, also fell victim to imperial suspicion. Persius, though not part of Nero’s intimate circle, was familiar with its style and even parodied it. Some ancient commentators claim fragments of Persius’ satire echo Nero’s own lines, though this seems more likely mockery than quotation.

Very little of Nero’s poetry survives. Dio tells us he wrote and performed a poem on the Trojan War — perhaps the same “Capture of Troy” he supposedly recited from his palace roof as Rome burned below. Seneca’s Naturales Quaestiones preserves one line on the iridescence of doves, while the scholia on Lucan cite three lines on the Tigris. These scraps, linked stylistically to Seneca’s Troades, suggest a shared literary language among Neronian authors.

Dio adds another revealing story:

“Nero was making preparations to write an epic narrating all the achievements of the Romans; and even before composing a line of it he began to consider the proper number of books, consulting among others Annaeus Cornutus...

This man he came very near putting to death and did deport to an island, because, while some were urging him to write four hundred books, Cornutus said that this was too many and nobody would read them...

Lucan, on the other hand, was debarred from writing poetry because he was receiving high praise for his work.”

Dio, Roman History 62.29.2–4

Such anecdotes capture the tension between Nero’s artistic ambitions and his insecurity. His reign fostered extraordinary literary production, yet it also consumed its creators. The emperor’s aesthetic fervor inspired what later generations would call the “Neronian Renaissance,” a revival of Augustan forms and genres under his patronage. But his erratic behavior and ruthless temper ensured that this cultural flowering perished with him.

Suetonius records the lampoons whispered by the people of Rome — cruel verses that condensed his legend into biting rhyme:

“Nero, Orestes, Alcmeon their mothers slew.”

“A calculation new. Nero his mother slew.”

“Who can deny the descent from Aeneas’ great line of our Nero?

One his mother took off, the other one took off his sire.”

“While our ruler twangs his lyre and the Parthian his bowstring,

Paean-singer our prince shall be, and Far-darter our foe.”

“Rome is becoming one house; off with you to Veii, Quirites!

If that house does not soon seize upon Veii as well.”

Suetonius, Nero 39

These epigrams encapsulate the contradictions of Nero’s image — parricide, performer, and megalomaniac — the emperor who wanted to rule as an artist. His final words, “What an artist dies in me!” (Qualis artifex pereo), sum up the self-image he never abandoned.

With his death, the dynasty ended — and so too did a distinct cultural epoch. For none of the Neronian writers survived him; their emperor was, in every sense, the last of them to go. (Introduction: The Neronian (Literary) ‘Renaissance’, by Martin T. Dinter, in A companion to the Neronian age, edited by Emma Buckley and Martin T. Dinter)

The Nero We Think We Know

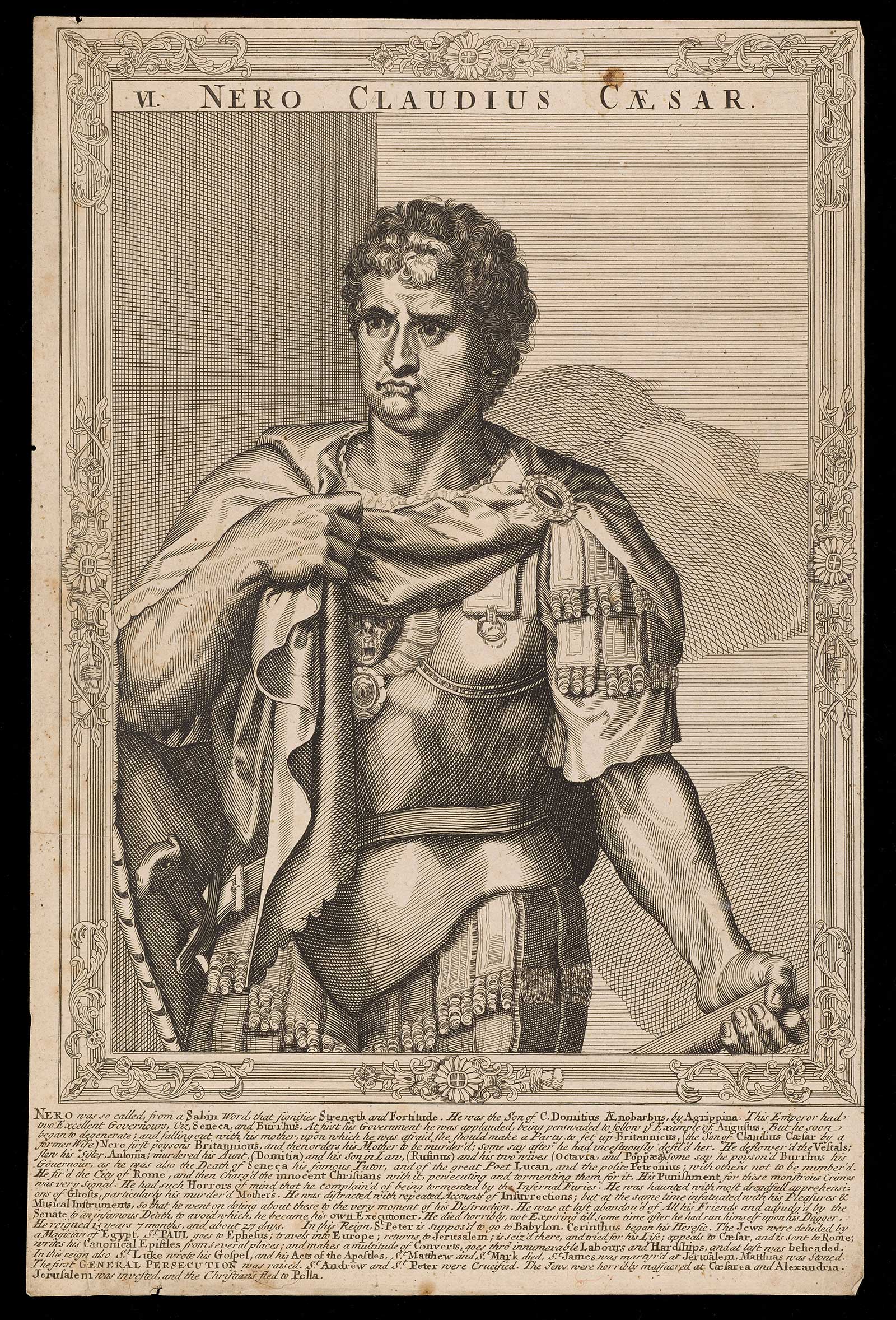

The Nero we know is the emperor who “fiddled while Rome burned,” indulged in “bizarre sex with a stable of partners (including his mother),” and was “amazingly extravagant.” He appears as a selfish child obsessed with the “arts,” irresponsible in governance, cruel, and incapable of endurance. This image, as enduring as it is lurid, comes to us primarily through three ancient voices—Tacitus, Cassius Dio, and Suetonius—whose writings mediate the space between the man and the myth.

The First Assessments

The legend of Nero began taking shape almost immediately after his death. Tacitus himself admits in the Annals that he drew upon earlier historians and that they disagreed about key events. He writes:

“Fabius Rusticus is behind the story that orders were written to Caecina Tuscus giving him command of the Praetorian Guard but that Burrus maintained his position with the help of Seneca. Pliny and Cluvius report that trust in Burrus was never in doubt. Of course, Fabius is inclined to praise Seneca with the aid of whose friendship he flourished.”

Tacitus, Annals 13.20.2

These early writers—Pliny the Elder, Fabius Rusticus, and Cluvius Rufus—became the foundation upon which all later accounts were built. Each wrote in the first years after Nero’s death, under the Flavian dynasty, whose legitimacy depended on contrasting its sober rule with Nero’s flamboyant tyranny. Pliny portrayed Nero as unworthy of succeeding Claudius; Fabius Rusticus, a protégé of Seneca, was predictably hostile; and Cluvius Rufus, once a court insider, chronicled events into the civil wars of AD 68–69.

Their works have not survived, but their influence pervades all later history. The favorable portrayals of Nero that existed during his lifetime quickly vanished, replaced by Flavian narratives of corruption and spectacle. As one later observer concluded,

“the only Nero we have is the Nero they created.”

Cassius Dio: Nero the Exhibitionist

Writing in the early third century, Cassius Dio inherited this tradition and shaped it for his age. His Roman History once spanned eighty books; of Nero’s reign, only Byzantine excerpts survive. Dio claimed to rely on reading, hearsay, and personal observation, though for Nero he could use only the first. His surviving narrative is therefore a “selection of selections,” filtered by medieval compilers—but it still preserves remarkable detail.

Dio alone tells us that during the Juvenalia, an octogenarian named Aelia Catella danced. He records that Nero sent agents, “pretending to be drunk and rioting,” to spread fires during the Great Fire of Rome. His account of Nero’s final two years—Tiridates’ visit, the emperor’s tour of Greece, and his triumphal return—fills the gap left by Tacitus, whose Annals break off in AD 66.

Dio’s inclusion of foreign affairs provides moral contrast. In Britain, Boudicca rallies her people with speeches that condemn Roman cruelty and mock Nero’s effeminacy; in Armenia, Corbulo appears as a paragon of old Roman virtue, only to be executed on Nero’s orders. Dio’s hostility is unrestrained. He writes bluntly that Nero:

“viewed the body of his dead mother and admired her beauty”

whereas Tacitus and Suetonius treat the story with hesitation.

Dio’s structure verges on biography. The Nero Books (61–63) begin with omens at birth, outline character, proceed year by year, and close with death and portents. This “biostructuring” turns history into moral theatre. For Dio and his epitomators, Nero is not a statesman but an “exhibitionist,” a “Roman curiosity.”

Tacitus: The Historian and the Drama of Decline

Tacitus, writing in the early second century, sought to write history rather than life. His Annals trace imperial rule from Tiberius to Nero, arranged by consular years and alternating domestic and foreign affairs. Nero dominates the final six books (13–18), though the text ends abruptly in AD 66. Tacitus weaves political analysis and psychological portraiture into an unbroken thread—the revelation of a ruler’s corruption over time.

At first, Nero’s reign shows promise. Tacitus notes wise appointments, fair taxation, modesty in honors, clemency, and effective rebuilding after the Great Fire with new safety measures. Later generations would mythologize these years into a quinquennium Neronis, the “five good years” of competent rule. But even from the outset, Tacitus speaks of Nero’s “hidden vices” and his “slippery nature,” restrained only by his mentors Burrus and Seneca.

Tacitus’ narrative follows a pattern of vivid tableaux—dramatic set pieces that reveal character. The poisoning of Britannicus becomes a story of legitimacy: Nero kills his younger stepbrother, “the true and worthy stock” of the Claudian house, whose song about his stolen birthright earned him death. Tacitus fills the banquet with terror and pity—Agrippina’s horror, Octavia’s silence, the guests frozen in disbelief.

The murder of Agrippina is another masterpiece of grim reconstruction. Ancient sources disagreed on every detail: the collapsing boat, the failed mechanism, the drowning plot. Tacitus sifts the confusion into coherence. When the boat fails, assassins finish the deed on land. He paints the silence before death:

“Now there was solitude and sudden noises and the signs of a final evil.”

The psychological terror echoes the banquet of Britannicus. Afterward, Agrippina’s ghost haunts Nero—

“entering with the Furies’ torches to the sound of distant trumpets.”

The tragedy continues with Octavia’s banishment and death, marking the end of the Claudian line. Tacitus describes the crowd’s pity as she sails for exile:

“Some still remembered Agrippina’s banishment by Tiberius and that of Julia by Claudius.” In the Octavia, the chorus bids her farewell with the lament that her wedding had been her funeral; Tacitus echoes this: “She was now a widow and no more than a sister.”

The Annals culminate in the Pisonian conspiracy of AD 65, the longest surviving episode. Senators, equestrians, and guards plot against Nero, but betrayals expose them all. Seneca and the philosopher Thrasea Paetus are forced to suicide. Tacitus, drawing from the acta senatus, lists nearly thirty victims. The episode, half political tragedy and half courtroom drama, displays both the corruption of power and the futility of resistance.

Tacitus’ effort to write sober history only makes Nero’s excesses more memorable. Critics faulted him for theatricality, yet the Nero of Tacitus—the artist, murderer, and haunted son—remains the most human and enduring version.

Suetonius: The Life of a Performer

Suetonius, writing a generation later, turned Nero’s story into biography. His Life of Nero follows the model of “birth to death,” arranged by topic—ancestry, virtues, vices, habits, and final fate. He opens with the Domitii Ahenobarbi, remarking:

“Although Nero discarded the virtues of his forefathers, he nonetheless perpetuated the vices of each of them as if they were inherited and a part of him from birth” (Nero 1.2*).

* His theme of illegitimacy runs through the entire narrative.

Suetonius begins with Nero’s virtues—piety, generosity, mercy, and affability—and devotes long sections to the emperor’s spectacles. The Juvenalia, Ludi Maximi, and Neronia are praised as acts of imperial beneficence. The reception of Tiridates is counted among these, introduced with the line:

“Not without thought would I report among the other entertainments he put on the entrance of Tiridates to Rome” (Nero 13.1*).*

Then comes the reversal:

“I have collected here these actions of his… to separate them from his abuses and crimes, which I shall relate from this point on” (Nero 19.3*).

* What follows is the portrait that fixed Nero’s image for posterity.

He trains obsessively with a lyre-player, sings publicly at Naples in AD 64, organizes his own cheering crowds, races chariots, and travels to Greece in AD 67 to compete in every contest he can—returning with trophies in parody of a military triumph. His reign descends into the catalogue of vices: petulentia, libido, luxuria, avaritia, crudelitas—insolence, lust, extravagance, greed, and cruelty. He murders Claudius, Britannicus, Agrippina, and others; persecutes after the Pisonian plot; and turns the Great Fire into “cruelty to the city walls.”

Suetonius’ narrative of Nero’s final days ranks among the most dramatic in Roman biography. Facing rebellion from Gaul, Nero flees Rome, hides among freedmen, and ends his life with the cry: “Qualis artifex pereo” — “What an artist dies in me!” After his death, the biographer notes, the people rejoiced yet some mourned; impostors appeared, claiming to be the lost emperor.

In a striking structural twist, Suetonius places Nero’s physical description and personal habits after his death—his poetry notebooks, craving for popularity, and longing for immortality—closing the life with a posthumous echo: the artist’s spirit refusing to die.

The Enduring Portrait

Across these traditions, Nero emerges not from a single pen but from layers of interpretation. The Flavian historians gave him infamy; Tacitus supplied depth; Dio magnified grotesquerie; Suetonius sealed it with theater. Even attempts to balance his record with administrative or military detail vanish beneath the magnetism of the set pieces—the murdered mother, the poisoned brother, the singing emperor, the burning city.

Roman lampoons immortalized that image:

“Nero, Orestes, Alcmeon their mothers slew.”

“A calculation new. Nero his mother slew.”

“Who can deny the descent from Aeneas’ great line of our Nero?

One his mother took off, the other one took off his sire.”

“While our ruler twangs his lyre and the Parthian his bowstring,

Paean-singer our prince shall be, and Far-darter our foe.”

“Rome is becoming one house; off with you to Veii, Quirites!

If that house does not soon seize upon Veii as well.”

When Nero cried, “What an artist dies in me!”, he unwittingly defined his own legacy. For in the centuries that followed, it was not the statesman or the reformer that survived—but the artist, forever dying in the flames of his own myth. ("Biographies of Nero" by Donna W. Hurley in “A companion to the Neronian age”, edited by Emma Buckley and Martin T. Dinter)

To be continued...

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: