Marking the Hours: The Roman Way of Measuring Time

The Romans employed various methods to measure time, integrating natural observations with technological innovations.

How did individuals in the Roman world structure their days or segment time? How did they perceive the stages of ageing and the progression of their lives? What role did the changing seasons play in shaping their daily routines?

How did these and other recurring cycles influence their views on health and illness? What part did measurement, and the tools used for it, play in these contexts? Moreover, how did they view their own lives within a larger historical framework, whether connected to actual or imagined past eras?

Temporal Realities in the Ancient World: Measuring and Understanding Time in Greco-Roman Society

P.N. Singer’s Time of the Ancients: Measurement, Theory, Experience, explores the concept of time in the Greco-Roman world by examining a variety of interconnected topics, including calendars, techniques of time measurement, socio-cultural constructions of time, and philosophical analyses. Singer highlights that, while these areas have been studied individually, there has been no comprehensive study that integrates them.

Singer argues that medical texts, particularly those by Galen, provide unique insights into time's division and measurement on three levels:

- Daily time (specific times of day for health prescriptions and diagnoses)

- Seasonal changes (their impact on health)

- The life cycle (from infancy to old age)

These texts offer a practical perspective that contrasts with sacred or ritualistic views of time. Instead, they focus on biological, environmental, and cosmic cycles, presenting time as a natural phenomenon rather than one defined by human constructs like calendars or festivals.

Galen's works serve as a focal point for Singer’s analysis due to their detailed discussions of time-related themes. Singer identifies four key contributions from Galen’s writings:

- Technical Knowledge: Galen provides the most comprehensive surviving account of constructing sundials and their relationship to water clocks, reflecting technological advancements in time measurement.

- Life Cycle Conceptions: His works explore the different stages of life, linking them to medical and lifestyle recommendations, offering a nuanced view of ageing and health.

- Clinical Practices: Galen describes the importance of precise temporal observation in diagnosis and treatment, highlighting how time was integrated into medical practices.

- Philosophical Reflections: He discusses the perception of time in relation to motion, speed, and rhythm, blending philosophical ideas with clinical experience.

The author notes that most surviving medical texts come from two main periods: the Hippocratic Corpus (5th–4th centuries BCE) and Galen's works (2nd century CE), with a significant gap in between. Galen’s texts dominate the evidence due to their volume and the absence of extensive medical writings from the intervening centuries. Consequently, he adopts a synchronic approach, focusing on Galen’s second-century Rome while using earlier texts to contextualize the intellectual and experiential traditions.

This approach aims to paint a cohesive picture of how time was understood, experienced, and measured in the Greco-Roman world, with Galen’s works acting as a bridge between earlier traditions and the medical practices of his era. Singer’s study provides a nuanced perspective on how time shaped both individual lives and broader societal structures in antiquity.

How did Romans Measure Time?

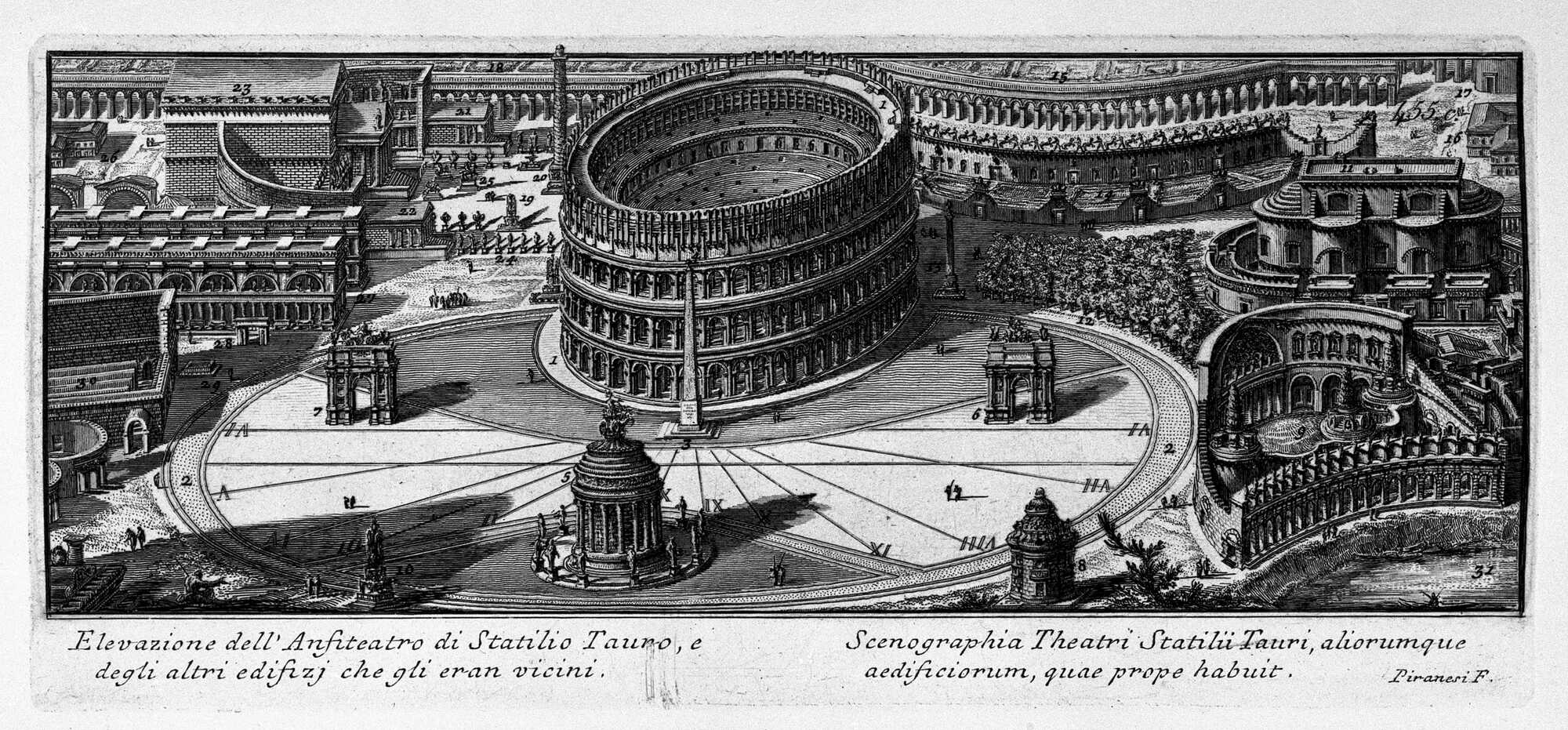

A towering obelisk dominated the Campus Martius in Rome, constructed in 10/9 BCE as part of the emperor Augustus' horologium. This impressive structure cast its shadow along a metal line embedded in the ground, which served as a meridian running due north. At noon, the shadow aligned with this line, marking dates along its length as the shadow lengthened or shortened with the progression of the year.

Elsewhere in the city, prominently displayed near the Forum—Rome’s hub of legal and commercial activity—were one or two sundials, dividing daylight into twelve equal segments. By the late second century CE, these sundials had been in place for over three centuries. Sundials were a common feature in cities throughout the Greco-Roman world, providing a visible means of marking the passage of time.

Image #1: vzR from Getty Images, by Canva

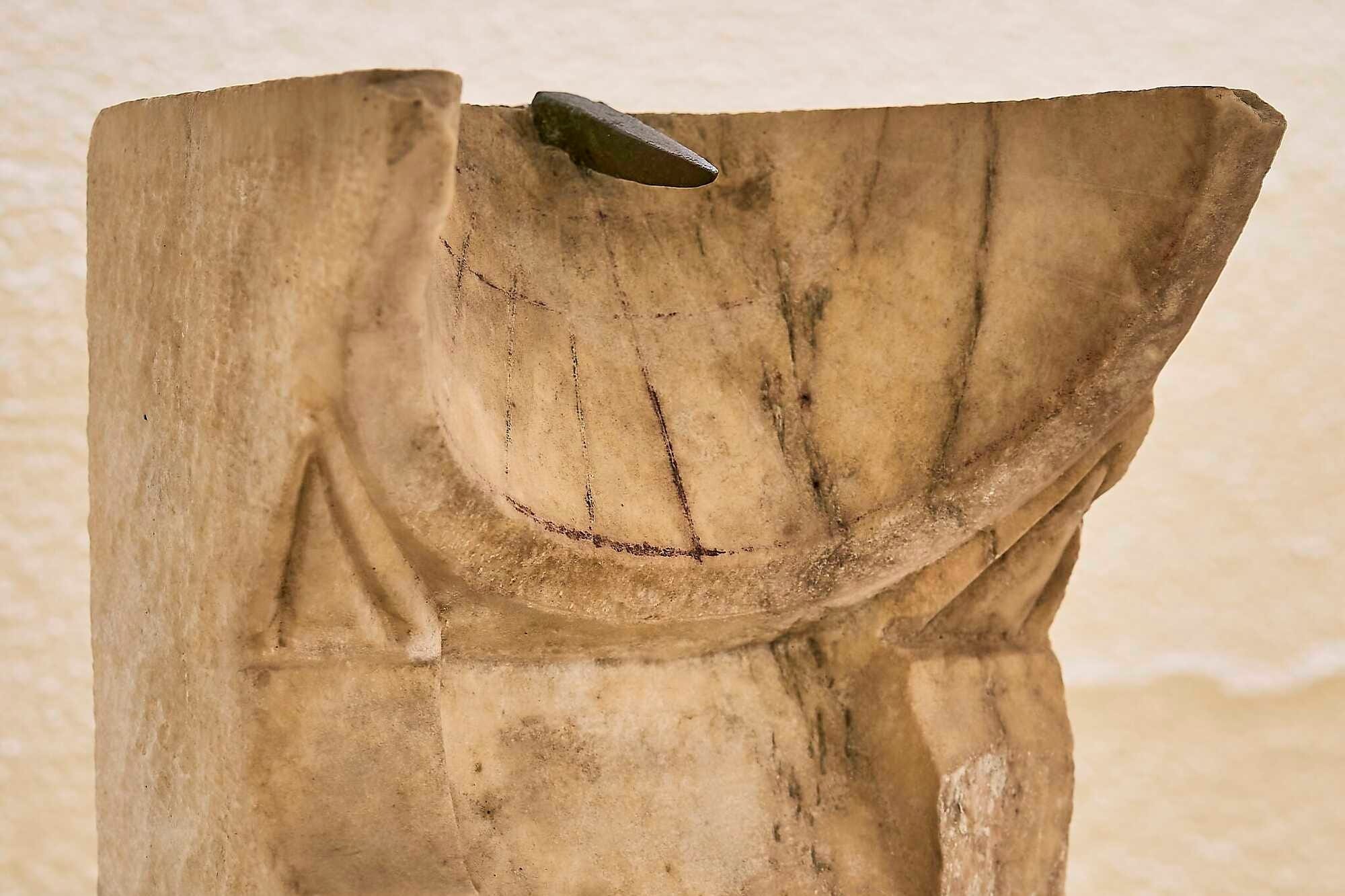

Image #2: gnuckx, upscaling by Roman Empire Times

Within the Forum, a visitor conducting business in the Basilica Aemilia et Fulvia might encounter another ancient timekeeping device: a water clock, or clepsydra. Installed in 159 BCE, this device likely divided the day into half-hour intervals. Clepsydras, especially in legal contexts, were simple outflow mechanisms designed to measure short, distinct periods.

However, more advanced versions of these water clocks existed as luxury items, often displayed in the homes of wealthy citizens. These elaborate clepsydras could measure hours and even fractions of hours, both day and night, with remarkable precision. Such devices, admired for their craftsmanship, symbolized the sophistication and status of their owners.

Some water clocks were also found in public spaces such as gymnasia, theaters, or sanctuaries by the second century CE, though little is known about their specific designs or capabilities. Additionally, portable or handheld sundials were used privately by the elite, serving more as symbols of affluence than practical tools. Archaeological evidence indicates that both handheld sundials and advanced water clocks were rare.

These examples illuminate the ancient Romans' approaches to time awareness and management. Public timekeeping devices in Rome marked large units of time, such as the time of day or the position of the year. In contrast, instruments used in business or legal settings measured smaller increments of time. At the private level, timekeeping devices in elite households were often more ornamental than utilitarian.

Together, these tools reveal a layered system of time perception, ranging from public utility to private prestige.

The Tower of Winds in the Roman forum in Athens, below the Acropolis, which also housed a water clock. Credits: rabbit75_cav, by Canva

The Horologium Augusti: A Monument of Time, Power, and Stability

The Horologium Augusti, an impressive public monument, served dual purposes: it functioned as a calendar to mark the progression of the year and as a daily indicator of noon. Inscribed along its meridian line were labels such as “beginning of spring” and “Etesian winds,” alongside zodiac signs and degree markers.

As the shadow cast by the obelisk shifted throughout the year, it aligned with these markers to indicate specific calendar events, such as the summer and winter solstices. This monument’s utility was both practical and symbolic. While passersby could regulate their day by noting the approach of midday, they could also observe the current position within the calendar year.

Beyond practical timekeeping, the Horologium reinforced the stability and reliability of the reformed Roman calendar, a testament to Augustus’ authority and his ability to impose order after a period of calendrical disarray. The alignment of the markings with civic festivals and days underscored the synchronization between the natural and civic order.

The monument also carried significant political weight, with its visibility from afar and its strategic placement near the Mausoleum Augusti and the Ara Pacis. These elements combined to project Augustus' power and the promise of a stable, orderly era under his rule.

Although traditionally referred to as a "horologium," the structure was not a sundial in the conventional sense. Its primary role was to indicate the seasons and midday, an important function dating back to early Greek gnomons, which prioritized tracking the year over measuring hours. While some scholars now propose alternate terms like “solarium” or “meridian,” the traditional name persists due to its broader connotations of time reckoning in both seasonal and hourly contexts.

The Evolution of the Concept of Time in Medicine: From ὧραι to Hours

The Greek term hōra originally referred to times of day or seasons, not fixed hours. In Archaic Greek literature and even into the fourth century BCE, there is scant evidence of the term being used to denote equal divisions of the day.

Although technology capable of dividing the day into equal parts existed by the fifth century BCE, hours were not widely employed for practical or medical purposes during this time. By the third century BCE, however, the concept of seasonal hours had gained traction, as evidenced by administrative systems, including Ptolemaic postal records, and medical texts.

This shift had a profound impact on medicine, particularly in the Roman imperial period. Earlier texts, such as the Hippocratic corpus, used approximate time references based on bodily events (e.g., "the middle of the day," "after food") rather than precise numbered hours. By contrast, later practitioners like Galen and the Methodists employed complex numerical systems that made precise hourly measurements central to medical diagnoses and treatments.

The transition from approximate time markers to numbered hours marked a significant evolution in both societal timekeeping and the medical field, allowing for more refined analysis and treatment of periodic diseases. This development bridged the temporal gap between the classical Hippocratic texts and the more systematic approaches of imperial-period doctors.

How was the Concept of the Day in the Roman Period?

Romans valued daily routines both as reflections of mundane realities and as expressions of larger cultural values. While Pliny the Younger criticized repetitive tasks for their monotony, he admired how the elder Spurinna's carefully structured days—marked by activities like bathing and socializing—gave purpose and order to life. This daily repetition served as a "rule" that defined personal identity and modeled disciplined living.

I don't think I ever spent a more delightful time than during my recent visit at Spurinna's house; indeed, I enjoyed myself so much that, if it is my fortune to grow old, there is no one whom I should prefer to take as my model in old age, as there is nothing more methodical than that time of life.

Personally, I like to see men map out their lives with the regularity of the fixed courses of the stars, and especially old men.

For while one is young a little disorder and rush, so to speak, is not unbecoming; but for old folks, whose days of exertion are past and in whom personal ambition is disgraceful, a placid and well-ordered life is highly suitable.

That is the principle upon which Spurinna acts most religiously; even trifles, or what would be trifles were they not of daily occurrence, he goes through in fixed order and, as it were, orbit.

Pliny the Younger, Letter To Calvisius

The Roman day was deeply intertwined with the social, cultural, and political frameworks of Roman life. It was divided and measured in various ways, reflecting natural, civic, and personal rhythms.

Roman timekeeping used overlapping systems, such as seasonal hours, nocturnal watches, and solar or equinoctial hours, often tied to natural cycles like sunrise, noon, and sunset. Devices like sundials, water clocks, and auditory signals complemented this, though precise timekeeping was not always prioritized.

The day served as a unit for organizing daily routines, ranging from morning duties (officia) to afternoon leisure (otium), as seen in Martial’s detailed accounts of a typical Roman day. Horace’s poetic reflections show how the Roman day linked immediate, cyclical time (e.g., the hours and seasons) with broader existential and historical considerations. His phrase “dust and shadow” captures both the ephemeral nature of human existence and the shadow of a gnomon on a sundial, symbolizing the merging of personal and cosmic time.

Roman civic life further shaped the day's temporal meaning. Calendrical designations (e.g., Kalends, Nones, Ides) and public commemorations added layers of significance, making each day a node in a larger cultural and historical narrative. Monuments like Augustus’ meridian obelisk linked the passage of a day with imperial symbolism, connecting personal time to Rome’s identity and legacy.

Daily time was not merely functional but a site where natural, civic, and personal rhythms converged. This blending of time scales—from hourly routines to seasonal cycles—allowed Romans to navigate their lives within an intricate framework of temporal meaning. The Roman day thus served as a primary interface for accessing and dramatizing broader temporal, historical, and cultural dynamics. (The ordered day: Quotidian time and forms of life in Ancient Rome, by James Ker)

How was Timekeeping in Ancient Rome?

The Roman calendar and timekeeping methods evolved significantly over centuries, heavily influenced by other civilizations. Initially, the Roman year consisted of 10 lunar months tied to agricultural cycles, with January and February added later.

Julius Caesar's Julian calendar reformed the system, introducing leap years and aligning the civil and astronomical years, though implementation challenges persisted, corrected later by Augustus. These adjustments created a more stable calendar, though festivals and holidays, often numbering over 150 days annually, constrained economic productivity.

Time division progressed from crude pre-meridies and post-meridies distinctions to more structured systems influenced by military needs and borrowed technologies. Sundials, first introduced from Greece in 293 BCE, and water clocks became prominent tools for time measurement.

By the second century BCE, Rome had numerous public sundials and various private innovations, like portable sundials and sophisticated water clocks, although these technologies were largely imported from Egypt, Greece, and Babylon.

An ancient Greek sundial displayed at the Archaeological Museum of Piraeus, Greece. Credits: George E. Koronaios, CC BY-SA 4.0

The Romans integrated these systems into daily life, dividing time into 12 daylight hours that expanded or contracted with the seasons. Despite adopting advanced timekeeping, Rome never advanced to the precision achieved during the industrial revolution, reflecting their pragmatic rather than innovative approach.

In essence, Roman timekeeping showcased a blend of borrowed ingenuity and adaptation, supporting their empire's administrative and cultural needs while mirroring broader patterns of power consolidation through control of time. (The Concept of Time in Ancient Rome, by Samuel L. Macey, International Social Science Review)

Which Timepieces did the Romans use?

The Romans (as already mentioned) heavily borrowed and adapted timekeeping technology from cultures they encountered throughout the Mediterranean, particularly the Greeks. Sundials, which use a shadow cast by an object to indicate time based on the sun's position, were a prime example of this influence.

The first recorded sundial in Rome, as noted by Pliny, was introduced in 293 BCE and was modeled on Greek designs. These timekeeping devices were primarily intended for public use, often placed in marketplaces, temples, and other communal spaces.

When sundials were first introduced in Rome, their function was not fully understood. For instance, a sundial taken from Sicily was used incorrectly in Rome for nearly a century. Despite this, the general population was not significantly affected by such inaccuracies. It was only in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE that a more scientific approach to timekeeping emerged, driven by a growing Roman interest in aligning their clocks with the cosmos and the calendar.

Units of Time

The Romans did not use minutes or seconds as we do today, but they did have the concept of an hour, which was their smallest unit of time. Unlike the fixed 60-minute hour we know, Roman hours varied with the seasons, following a method borrowed from Ancient Egypt. They divided daylight and nighttime into 12 segments each, regardless of the changing lengths of day and night throughout the year. As a result, an hour in winter could last about 45 minutes, while in summer, it could stretch to roughly 75 minutes.

Roman timekeeping devices, like sundials, typically displayed hours without further subdivisions, as noted by Denis Savoie, an astronomer specializing in sundials. Hours served as a general guide for scheduling meetings, meals, and activities, but they lacked the precision we rely on today. Alexander Jones, curator of the exhibition Time and Cosmos in Greco-Roman Antiquity, remarked that a 15-minute delay would not have been a source of frustration in Roman times.

The Romans were aware of the imprecision of their system but did not feel the need to develop more accurate timekeeping until the third and second centuries BCE. By 54 BCE, Julius Caesar noted that nighttime hours in Britain were longer than those in Rome. This discrepancy, due to differences in latitude, was demonstrated using a water-based timepiece that could measure standardized periods, regardless of variable sunlight.

Portable sundials allowed Romans to approximate the time even when traveling to distant regions like Ethiopia, Spain, or Palestine. These devices were considered innovative and prestigious, as evidenced by the number of surviving examples. However, not everyone appreciated the segmentation of the day. In one of his plays, the Roman playwright Plautus lamented how sundials "chopped the day into pieces," reflecting a certain resistance to the growing emphasis on dividing time into increments.

In 25 BCE, the Roman author and architect Vitruvius detailed various types of sundials and their Greek inventors in Book IX of De Architectura. He used the term “arachnen,” meaning “spider’s web,” to describe the network of hour lines engraved into the stone, a feature common to all the sundials he mentioned. The types of sundials he listed were primarily distinguished by the surface onto which the shadow was cast, a classification method similar to modern categorizations.

Vitruvius noted that while there was extensive knowledge about clocks, including portable ones, constructing a sundial required a deep understanding of the celestial sphere. This complexity meant that timekeeping devices were largely confined to the elite, as such expertise was beyond the grasp of the general population.

Sundials, Water Clocks, and Obelisks

As we mentioned, the Romans employed three primary types of timepieces: sundials, klepsydras (water clocks), and obelisks. These timekeeping methods, heavily influenced by Greek and Egyptian innovations, relied on natural elements like the sun and water.

Sundials were popular in public spaces such as temples and marketplaces, where they used the shadow of a gnomon (a vertical rod or object) to indicate time. While effective during daylight, they were useless at night or on cloudy days. Sundials in Rome often needed adjustments for accuracy, especially since the first ones brought from Greece or Egypt were designed for different latitudes.

Despite their limitations, sundials became widespread, with more than 13 variations documented by the Roman architect Vitruvius.

Youth and Time (sundial on the right), a painting by John William Godward. Public domain

Obelisks functioned similarly to sundials but on a grander scale. For example, the Solarium Augusti, built during Augustus’ reign, marked time using the shadow of a 30-meter obelisk on a marble surface engraved with hour lines. This monument not only told time but also symbolized Augustus' authority and his conquest of Egypt.

Klepsydras were practical for interiors, nighttime, or overcast days. These devices worked by allowing water to flow steadily from a container, marking a predetermined length of time. Unlike sundials, they were unaffected by seasonal changes or latitude, making them more reliable. Similar to modern sand timers (hourglasses), klepsydras were primarily used in legal, military, and domestic settings.

Vitruvius detailed four main types of sundials:

- Spherical: Resembling a hollow dome or globe

- Conical: Shaped like a cone, often cut at various angles

- Planar: Featuring a flat surface to track shadows

- Cylindrical: Often called "shepherd’s dials," designed for portability with time markers etched along the staff

As aforementioned, Romans also developed portable sundials, useful for travelers or the military. These dials, adjusted for latitude and time of year, were prized by elites but required manual calibration. Errors in adjustment could lead to inaccuracies, but their portability allowed Romans to track time in distant regions like Spain or Palestine.

The Romans adopted and refined these tools, using them to help both the elite and the general public keep track of time in their increasingly organized society. Unlike today, when the time is instantly accessible, understanding the hour in ancient Rome required observing the natural movements of the stars, Earth, and Sun or consulting a public or personal timepiece—an effort far removed from the ease of modern clocks.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: