Gladiatrix: Scent of a Woman, in the Arena

Female gladiators, known as "gladiatrices," were a relatively rare phenomenon in ancient Rome compared to their male counterparts, but they did exist and played a significant role in the spectacle of gladiatorial combat.

A gladiatrix, was a female gladiator in ancient Rome. Like their male counterparts, gladiatrices engaged in combat with each other or with wild animals to entertain audiences during games and festivals.

Gladiation in Ancient Rome

The gladiatorial combats are part of the broader context of the ludi, (public games for the entertainment of the Roman people) which have been recorded in Rome as early as the 4th-3rd century BC. In addition to the ludi scaenici (dramatic performances) and circenses (chariot races), the ludi gladiatorii, venationes, and naumachia increasingly captivated ancient audiences. Initially, these spectacles were organized in the Forum or other public spaces, but they later found their primary venues in amphitheaters.

A notable aspect of the ludi is the sense of civic belonging that the spectators exhibited by participating in these events. The ludi also held a mystical-religious element, as the killings during the spectacles were seen as sacred ceremonies and served as exempla for the community involved. The ludi gladiatorii are also referred to as munera gladiatoria, particularly from the Imperial age onward. The term derives from the Latin word munus, indicating a duty performed for significant individuals and the public.

Gladiators were officially introduced to Rome in 264 BC. According to primary sources, Marcus and Decimus Pera, sons of the late Brutus Pera, organized fights between three pairs of gladiators in the Foro Boario during their father's funeral rites.

Livy writes about the gladiator games and suggests they were first introduced in Campania. The historian recounts that following the Roman and Campanian victory over the Samnites in 310/309 BC, the Campanians made the defeated Samnites' weapons part of the gladiators' attire during banquets, referring to these gladiators as Samnites.

In Capua, Campania, there were notable gladiator schools. The gladiators resided in barracks known as familiae and were overseen by a lanista, who was typically the gym's owner and sometimes the gladiators' instructor. The lanista was responsible for providing the editores ludorum (the ones responsible for organizing the games with the gladiators-the producers of the spectacle) with all necessities for organizing the games.

From the Augustan era onwards, gladiators were categorized into groups such as thraeces, murmillones, retiarii, equites, and oplomachi. While many fighters were slaves, freedmen, and prisoners, there were also instances of free men voluntarily becoming gladiators. Such cases were significant enough that in 11 AD and 19 AD, two Senatus Consults were issued to prohibit senators and knights from becoming gladiators.

The munera gladiatoria, held in the afternoon segment of the spectacula, were regularly organized by emperors and wealthy private citizens until the Severan age. From this period, due to the economic decline in the western part of the empire, this type of entertainment began to wane. Additionally, the rise of Christianity and Constantine's Edict led emperors to distance themselves from gladiatorial combat. By the fifth century, there were no further records of munera gladiatorial. (Angela Gatti, Munera gladiatoria and female gladiators in the ancient world)

Female Gladiators in Roman Historical Records

The term “gladiatrix” belongs to modern terminology. Some sources claim that female gladiators were referred to as ludia, the feminine form of ludius or ludio (stage performer). The actual meaning of the word ludia is the gladiator’s wife. Decimus Junius Juvenalis, (Juvenal) and Martial clearly describe a gladiator’s wife or lover when using the word ludia.

When Tacitus refers to the "women of rank" (Annals) who appeared in the amphitheater, he uses the term feminae, denoting respectable wives and daughters of Roman citizens. Juvenal, on the other hand, uses the term mulier to describe a woman who shamelessly rejects her femininity to train as a gladiator, and Petronius uses the same term to describe a female gladiator.

Thus, a distinction was made between the lady who does not willingly degrade herself by performing in the arena, and the woman who does. However, neither was ever referred to as a gladiator; femina and mulier were used out of necessity.

References to female gladiators, or gladiatrices, almost always pertain to their appearances in Rome. Tacitus and Cassius Dio mention female gladiators during Nero's reign on one or possibly two occasions. Petronius refers to a female charioteer in Satyricon 45.

Martial and Dio document female beast-hunters at the games inaugurating the Flavian Amphitheatre under Titus, and Statius, Suetonius, and Dio record female gladiators under Domitian on at least two occasions. Juvenal's depiction of an elite woman training in a ludus, while published no earlier than AD 115, likely draws inspiration from Domitian's reign as well.

It was in AD 200, that Septimius Severus prohibited women from participating in the arena. Cassius Dio records that during a gymnastic contest:

"…women took part, vying with one another most fiercely, with the result that jokes were made about other very distinguished women as well. Therefore it was henceforth forbidden for any woman, no matter what her origin, to fight in single combat"

Emperors often spent more lavishly on games than the aristocracy. Suetonius describes how Domitian regularly hosted grand and costly spectacles in both the amphitheater and the Circus, featuring not only male but also female combatants. Dio similarly recounts such events. Statius, in Silvae, praises the variety and generosity of Domitian’s Saturnalia, which included combats between women.

The games that dedicated the Colosseum were particularly magnificent, including female venatores, with Dio noting that 9,000 animals were killed during the bloody inauguration of the new arena. Thus, on both imperial and private levels, female gladiators were markers of noteworthy games, reflecting the benevolence and high status of the emperors who organized them.

Post-96 AD, evidence becomes scarce, likely due to a decrease in literary production following Trajan's death. One inscription, undated but thought to be from the second half of the second century AD, was erected by Hostilianus, who claims to be the first in Ostia since Rome's founding to make women fight.

Dio is the only literary source mentioning female gladiators after Domitian, referring to Septimius Severus' ban in AD 200. Although he identifies the event that prompted the ban as a gymnastic competition and the participants as athletes, he states the ban was against women appearing in single combat (monomachiis). (Anna McCullough, Female Gladiators in Imperial Rome: Literary Context and Historical Fact)

"There was another exhibition that was at once most disgraceful and most shocking, when men and women not only of the equestrian but even of the senatorial order appeared as performers in the orchestra, in the Circus, and in the hunting-theatre [Colosseum], like those who are held in lowest esteem.

Some of them played the flute and danced in pantomimes or acted in tragedies and comedies or sang to the lyre; they drove horses, killed wild beasts and fought as gladiators, some willingly and some sore against their will."

Cassio Dio, Roman History

“Domitian presented many extravagant entertainments in the Colosseum and the Circus. Besides the usual two-horse chariot races he staged a couple of battles, one for infantry, the other for cavalry; a sea-fight in the amphitheatre; wild-beast hunts; gladiatorial shows by torchlight in which women as well as men took part.”

Saetonius, Life of Domitian

Gladiatrix in Roman Archaeological Findings

The sources associate female gladiators with particularly expensive and ostentatious games, showcasing personal wealth and imperial extravagance and decadence. This context explains the absence of references to female gladiators during the reign of Augustus.

The opulent and costly games featuring women did not align with the image of the Empire and emperor that Augustus promoted through his literary circles or his policy of moral and cultural renewal. Although he did not explicitly ban mentions of women in the arena, Augustus discouraged praise of the extravagant context in which female gladiators appeared, both in literary depictions and in reality.

Augustan (and later Neronian) propaganda highlighted "the court as a center of literary patronage and the expectation that the image of the reigning prince would be appropriately burnished and his policy goals depicted in a favorable light." This mission embodied the Golden Age principles of "peace, justice, beauty, and culture." The conservative, neotraditional Roman moral virtues Augustus sought to reinforce through legislation and literature conflicted with the decadence that produced female gladiators. With the priority on promoting these noble principles, authors aiming to celebrate imperial luxury and grandeur had to navigate Augustus' influence carefully.

Beyond literary references, archaeological findings also substantiate the existence of female gladiators. Notable evidence includes an inscription at the Roman port of Ostia, a shard of inscribed pottery unearthed in Leicester, and a carved relief from Halicarnassus that depicts two female gladiators.

The second piece of evidence is a fragment of red pottery with a drilled hole, possibly intended to be worn as a necklace. It is inscribed with: VERECVNDA LVDIA LVCIUS GLADIATOR, which Jackson R, translated it as "Verecunda the dancer (or female gladiator), Lucius the gladiator". The purpose of the item remains uncertain, but the inscription suggests Verecunda may have been a female gladiator, potentially fighting in the same troupe as Lucius.

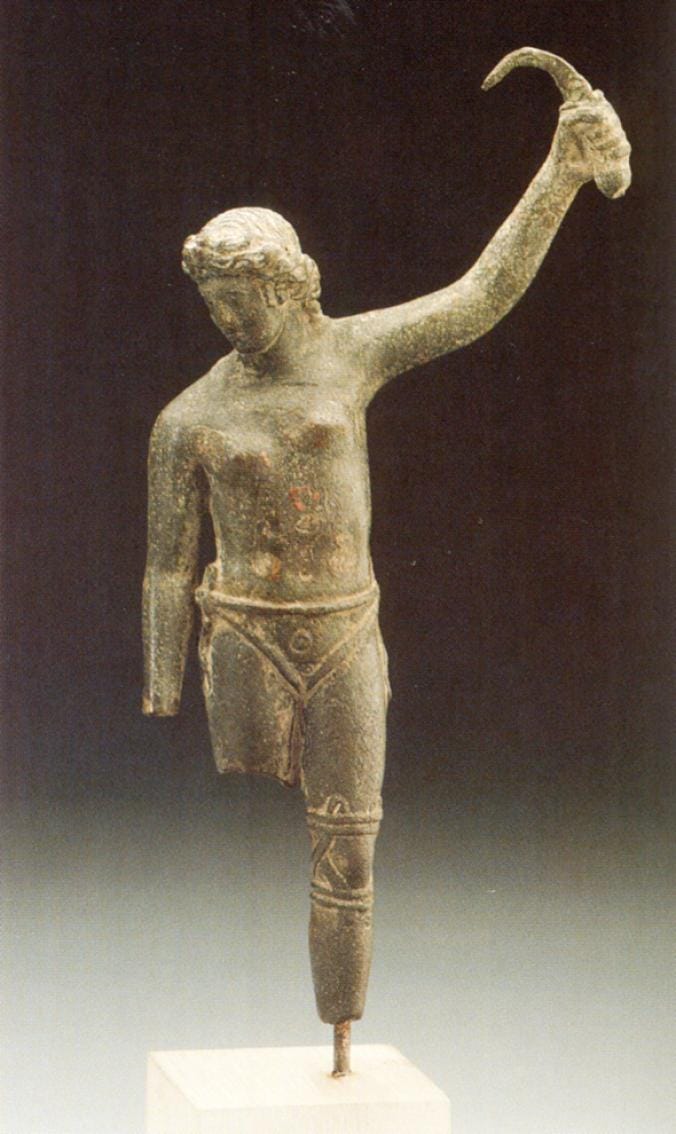

The final piece of direct evidence is a marble relief from the first or second century AD, found in Halicarnassus and now displayed in the British Museum. This relief is the most convincing evidence of female gladiators, as it explicitly depicts two women in combat. The figures are dressed and equipped similarly to male provocator gladiators, wearing a loincloth (subligaculum), greaves, and an arm protector (manica) on their sword-wielding arms. Both are armed with a shield and sword but lack helmets or shirts.

They are named ΑΜΑΖΩΝ (Amazon) and ΑΧΙΛΛΙΑ (Achillia), clearly indicating their gender through these "singularly appropriate" noms de guerre. The inscription ΑΠΕΛΥΘΗΣΑΝ (missae sunt) above them means they received an honorable discharge from the arena.

The relief serves as a monument to their valiant effort, marking a significant event worthy of commemoration due to its rarity and the fact that the protagonists were women. The existence of this relief suggests that female gladiatorial combat was taken seriously enough to be commemorated in a lasting and valuable medium. (Steven Ross Murrey, Female Gladiators of the Ancient Roman World)

"Who has not seen the dummies of wood they slash at and batter

Whether with swords or with spears, going through all the moves?

These are the girls who blast on trumpets in honour of Flora.

Or, it may be, they have deeper designs, and are really preparing for the arena itself.

How can a woman be decent, sticking her head in a helmet, denying her sex she was born with?

Manly feats they adore, but they wouldn't want to be men,

Poor weak things (they think), how little they really enjoy it!

What great honour it is for a husband to see, at an auction

Where his wife's effects are up for sale, belts, greaves, manica and plumes!

Hear her grunt and groan as she works at it, parrying, thrusting;

See her neck bent down under the weight of her helmet.

Look at the rolls of bandage and tape, so her legs look like tree trunks.

Then have a laugh for yourself after the practice is over,

Armour and weapons are put down, and she squats as she uses the vessel.

Ah, degenerate girls of the line of our praetors and consuls,

Tell us, whom have you seen got up in any such fashion,

Panting and sweating like this? No gladiators wench,

No tough strip-tease broad would ever so much as attempt it."

The Satires of Juvenal - The Female Gladiators

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: