From Toga to Today: How Ancient Rome Still Echoes Through Modern Culture

From marble forums to Hollywood sets, the legacy of Ancient Rome continues to echo across today’s cultural landscape. In many ways, Rome never truly fell—it was reimagined.

It starts with a movie scene, a slogan in politics, or a marble bust gazing from a museum wall—but look closer, and you’ll notice the imprint of Rome everywhere. From cinema and literature to architecture and ideals of power, the echoes of the empire still murmur through our modern world. What is it about ancient Rome that captivates us so deeply? Why does a civilization lost to time continue to shape how we tell stories, build cities, and imagine greatness?

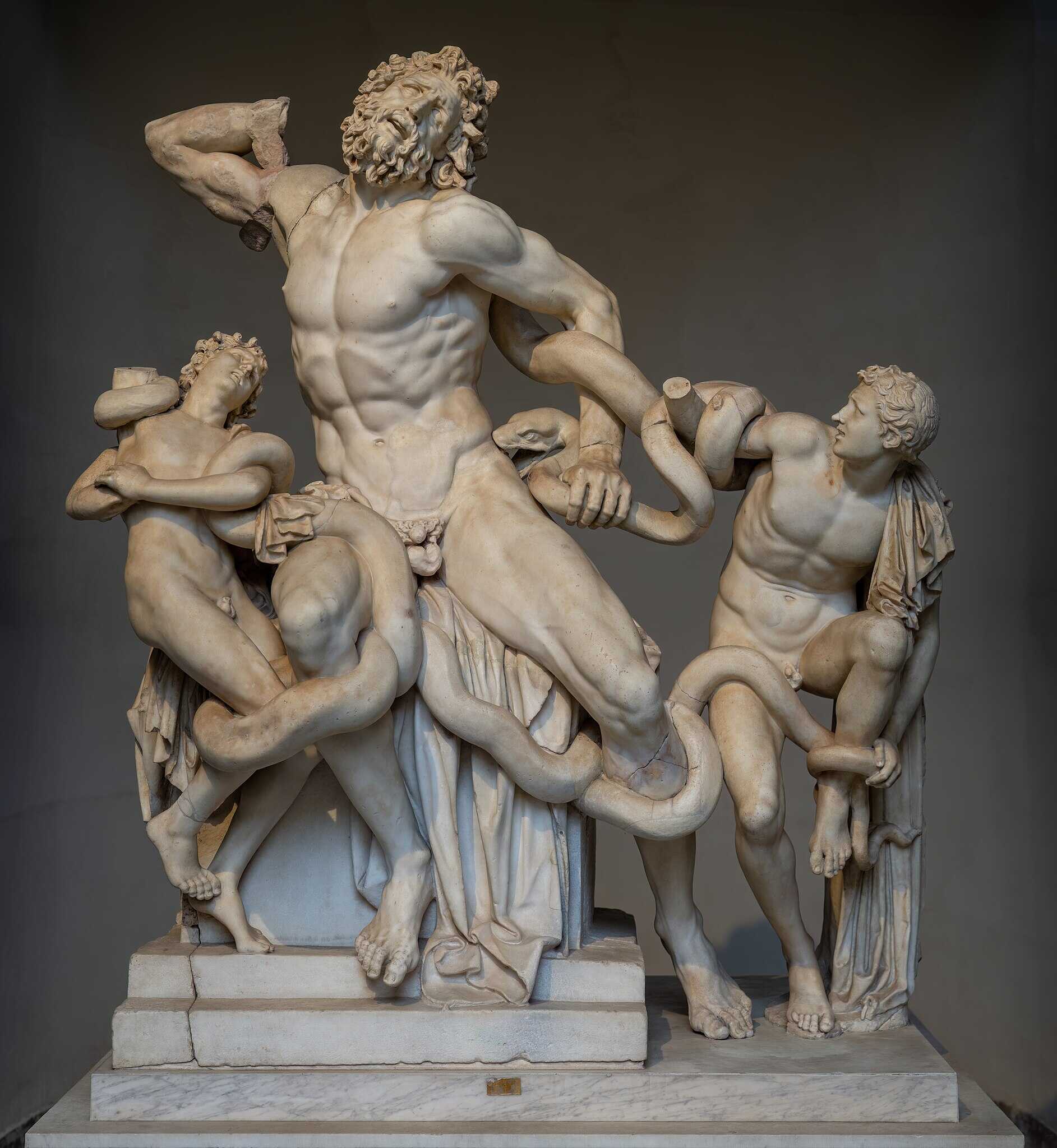

Rome Reimagined: How Popular Culture Cast the Caesars in Stone and Spectacle

While the Roman Republic once inspired the democratic ideals of the United States, the Rome that captivates modern audiences—especially in twentieth-century British and American popular culture—isn’t one of senatorial debate or civic virtue. Instead, it's the empire of emperors, not institutions, that dominates the screen and stage.

Nero, mad and melodramatic, tends to overshadow intellectuals like Petronius. This imagined Rome is fierce, indulgent, and saturated in vice—defined more by its parades of military might, gladiator games, lavish banquets, and orgiastic excess than by laws or governance.

Frequently, the lens through which this imperial world is shown belongs to its victims: Christians, slaves, Jews, or rebels—outsiders trapped within the empire’s grasp. Their stories provide a critical view from within.

Meanwhile, modern audiences watch from a privileged distance, always conscious of Rome’s inevitable downfall. This narrative tension gives viewers a dual experience: they feel superior in hindsight yet strangely connected to the empire's grandeur and decline.

Popular portrayals of Rome don’t just reflect the past; they reframe the present.

Ciaran Hinds as Gaius Julius Caesar in HBO’s Rome mini-series. Credits: HBO

By projecting modern power struggles, desires, and anxieties onto ancient Rome, creators offer audiences a mirror wrapped in marble. These stories provide a stage where the extremes of politics, luxury, and sexuality play out safely in historical costume—offering both critique and validation of the world we live in, all under the guise of exploring a shared cultural heritage.

Across film, literature, theater, and architecture, the image of ancient Rome has been repeatedly reshaped to reflect the needs, desires, and fantasies of modern creators. Whether it’s Colleen McCullough striving for historical accuracy in her novels or the extravagant, stylized Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, these reimaginings often take liberties—sometimes subtly, sometimes wildly—with what ancient Rome may have actually been.

Larry Gelbart, co-writer of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, described his adaptation of Plautus as a creative process involving "digging around" and "fashioning a cat’s cradle of a plot." The outcome was a transformation: Roman slaves became Jewish comedians, and ancient Rome found itself relocated to something like Brooklyn. This playful reimagining is just one of many examples showing how Rome is constantly reborn in popular culture, tailored to different audiences, times, and agendas.

In some cases, figures from Roman history are given long afterlives through reinterpretation. Take Saint Sebastian: Derek Jarman’s 1970s film drew on centuries of imagery—from Renaissance art to Baroque sculpture to homoerotic photography—to explore themes of beauty, suffering, and desire. Similarly, the story of Spartacus has been refashioned across eras: in 1760, he was the Enlightenment hero; in 1810, a Romantic figure; in the mid-20th century, a communist icon tamed for Hollywood’s big screen.

Hollywood’s influence on the image of Rome is inescapable. Most of its grand Roman epics were adapted from 19th-century novels and plays, themselves shaped by Victorian fantasies of power and spectacle. Ben-Hur, Quo Vadis?, and The Sign of the Cross were not just novels—they became blueprints for Rome on film.

Directors like William Wyler studied previous Roman films to get the “look” right for their own productions, leading to an echo chamber where cinematic Romes endlessly recycle one another. Even parodies, like Carry On Cleo (1964), which aimed to mock the genre, couldn’t escape Hollywood’s influence. It borrowed costumes and props from the lavish Cleopatra (1963) and ended up reinforcing many of the same visual tropes it sought to undermine.

The case of Richard Lester’s 1966 adaptation of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum is particularly telling. He intended to strip away the glossy marble of Hollywood's Rome to show something more authentic—gritty, unjust, and full of real human struggle. Yet even he couldn’t fully escape the cinematic past.

He filmed on leftover sets from The Fall of the Roman Empire, simply dirtied them up, added mud, rotting vegetables, and Spanish extras to give the illusion of grime. But beneath that new layer, Hollywood’s Rome still glimmered faintly, like a ghost of grandeur just below the surface.

In the end, every Rome we see—whether on page, stage, or screen—is a remix. A reflection not just of what was, but of what we wish to see: power, decadence, tragedy, and identity, all projected through the eternal marble mirror of an imagined empire.

Rome as Mirror and Warning: How Hollywood Made an Empire of Meaning

Every time Rome is adapted in modern storytelling, it becomes a mirror—a way for societies to explore their own anxieties about power, politics, morality, and empire. Hollywood’s epics of the 1950s, especially, didn’t just depict Roman cruelty or grandeur—they used it to reflect contemporary issues like Cold War fears, totalitarianism, consumerism, and sexual norms.

Rome was alternately cast as the enemy or the ancestor, with audiences encouraged to see themselves as either fundamentally unlike the Romans or disturbingly similar. Cinematic Romans stood in for Nazis, fascists, communists, and colonial oppressors, while Christians, Jews, and slaves became the righteous “us.”

This dynamic also allowed Americans to distance themselves from their own imperial reality, projecting their ideals onto Rome’s victims while condemning Roman excess—political tyranny, moral decay, and sexual deviance. From orgies to cynical senators, Hollywood’s Rome served as both a moral spectacle and a political allegory.

Even accents mattered: evil Romans spoke with British accents, while freedom-loving rebels spoke American, enacting a colonial revenge fantasy on screen. In this way, Rome became a stage for America’s own internal debates—timeless, flexible, and always revealing.

Projection in popular portrayals of ancient Rome is rarely clear-cut.

Karl Théodore Piloty’s painting, Under the Arena. Public domain

Films often engage in a complex blend of identification and distancing, inviting viewers to enjoy Roman decadence while simultaneously rejecting its values. In Sebastiane (1976), for instance, Derek Jarman uses the Roman setting to both celebrate homoerotic desire and critique Britain’s repressive stance on homosexuality, drawing on the long-established symbolic link between Rome and male same-sex desire.

Hollywood epics, follow a similar pattern: while the narrative encourages viewers to side with early Christians and reject Roman excess, the sheer spectacle of Roman luxury, grandeur, and eroticism invites visual pleasure and consumer desire. This duality—condemnation of decadence on one hand and indulgence in its cinematic form on the other—mirrors postwar American culture’s tensions between morality and consumption, guilt and pleasure.

Ultimately, these films allow audiences to process cultural anxieties—about gender, sexuality, or power—indirectly, by projecting them onto the Romans. Throughout most of the twentieth century, portrayals of imperial Rome in popular culture tended to emphasize a sense of detachment or a conflicted mix of fascination and disapproval. But by the century’s end, this perspective began to shift.

The once-comfortable assertion of the 1950s—“We are not the Romans”—and the anxious questioning that followed—“Have we become them?”—gave way to a more self-assured embrace: “Be like the Romans!” In newer depictions, Rome's associations with moral decay are replaced by an alluring vision of unrestrained power and extravagant pleasure.

When imperial might and vice are reimagined as desirable signs of wealth and success, Rome becomes something to aspire to rather than condemn. For instance, author Colleen McCullough, while writing her Masters of Rome series, described herself as fully inhabiting the mindset of a Roman.

Her novels, particularly resonant with female readers, invite a fantasy of empowerment—identifying not with Rome’s victims, but with its elite, indulging in visions of unchecked influence and prosperity.

Alessandro Pigna’s painting, vividly reminding us of the human evolution from the Roman toga, to today’s world. Public domain

Similarly, Jay Sarno, the creator of Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, sought to recreate an atmosphere of unapologetic luxury, allowing guests to step into the shoes of decadent Roman elites. While early Hollywood often warned against Roman excess, Caesars celebrates it.

The resort mirrors Rome not as a cautionary tale, but as a fantasy world dedicated to pleasure and consumption. This echoes the legacy of 1930s Hollywood, which pioneered the marketing of Roman imagery through tie-in merchandise like Quo Vadis pajamas.

At the lavish Forum Shops next door—a Roman-themed mall opened in 1992—the empire becomes a backdrop for shopping, its grandeur co-opted by modern capitalism. Here, consumerism is not just tolerated but elevated, cloaked in classical aesthetics. In this reinterpretation, imperial Rome symbolizes affluence and leisure—an aspirational brand for an America increasingly comfortable with its own appetite for spectacle and spending. (Imperial projections: Ancient Rome in modern popular culture, edited by Sandra R. Joshel, Margaret Malamud, Donald T. McGuire)

Ancient Lessons for the Modern World

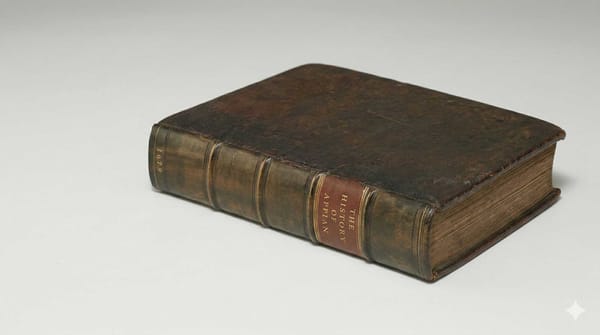

In a sharp review for Foreign Affairs, Michael Fontaine explores how Mary Beard’s SPQR brings ancient Rome vividly—and unsettlingly—close to home.

Michael Fontaine, a professor of classics at Cornell University, opens his review of Mary Beard’s SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome with admiration for her ability to make the distant past feel startlingly relevant. Beard, he explains, doesn’t just chart the Roman Republic’s rise and fall; she reanimates it with a wit and clarity that speak directly to the concerns of modern readers. Her Rome is not fossilized in marble but breathing—vibrant, flawed, and painfully familiar.

Rather than beginning with Romulus and Remus, Beard chooses to open in 63 BCE, the year of Cicero’s consulship. Cicero, an outsider from the provinces who rose through sheer talent, becomes a symbolic figure for contemporary political outsiders. Fontaine notes how Beard’s narrative recasts him as “a thoroughly modern politician,” facing a populist threat and navigating a Senate paralyzed by fear.

Throughout the book, Beard draws subtle, thought-provoking lines between ancient and modern dilemmas.

Discussions on citizenship laws echo today’s debates on immigration and national identity. The Roman Senate’s anxiety over conspiracies feels eerily reminiscent of political fear-mongering in the post-9/11 era. Beard never makes the connections overt—but as Fontaine writes, readers will find “more analogies than they may be comfortable with.”

Her Rome is not a golden age to be worshipped, but a society grappling with inequality, propaganda, and the slow erosion of republican ideals. Fontaine praises her for this honesty—particularly in dealing with Rome’s imperial brutality, such as Caesar’s massacres in Gaul. Rather than glorify conquest, Beard frames it with a modern conscience: “Today we would call them war crimes,” she writes. Fontaine calls this “one of the most sobering and memorable lines in the book.”

What ultimately emerges is a version of Rome that resists simple nostalgia. SPQR is not about how we should return to Rome, but how we never really left it. Fontaine concludes that Beard “shows we have an enormous amount to learn—not just about the past, but about ourselves.” (What Rome Can Teach Us Today: Ancient Lessons for Modern Politics, Reviewed Work: SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome by MARY BEARD Review by: Michael Fontaine)

Rome's Enduring Influence: Foundations of the Modern Global Order

In their paper “Significance and Impact of Ancient Rome and Its Relevance in the Current Global Order,” Vishnu Prabhu K.S. and Dr. Laxmi Dhar Dwivedi explore how the Roman Empire continues to shape modern civilization—not as a distant relic of the past, but as a foundational blueprint for political, cultural, economic, and strategic life today.

The authors draw attention to how the Roman combination of military prowess and cultural assimilation mirrors today’s power dynamics. Ancient Rome was not solely an empire of conquest; it was a civilization that absorbed and adapted.

Its embrace of Greek aesthetics, foreign customs, and skilled immigrants speaks to a soft power dynamic that resonates with modern forms of globalization. Rome’s strength lay not only in its legions but in its ability to culturally integrate, a trait seen in today’s international alliances and migration policies.

Prabhu and Dwivedi also emphasize the institutional and diplomatic legacy of Rome. Long before the advent of international law, Rome developed the ius gentium—a legal framework for dealing with non-citizens that served as an early form of international law.

Military decisions often required approval from both the Senate and religious authorities, showing a system of checks and balances that echoes in modern democratic governance. In this way, Rome becomes more than a historical case—it stands as a structural ancestor to organizations like the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, or even NATO.

Military innovation, too, forms a critical part of the analysis. The authors highlight the strategies of generals like Scipio Africanus and Fabius Maximus. The latter’s tactics of delay and attrition—later known as the Fabian strategy—have influenced warfare for centuries, reappearing in contexts as varied as WWII or Cold War intelligence planning.

Rome’s economic model is another element with lasting significance. With its far-reaching trade in wine, oil, ceramics, and luxury goods, Rome was a proto-global economy. Its taxation system and the bureaucratic link between tax collection and the central authority remain a model for state-building. Even in modern Italy’s economy—rooted in exports of fashion, design, and gastronomy—the echoes of that imperial infrastructure are visible.

The thesis also traces the architectural and legal inheritance passed down from Roman civilization. Vitruvius’ treatise De Architectura influenced not only Renaissance urban design but continues to inform civic planning today. Roman legal concepts survive in modern international law, reinforcing the argument that Roman frameworks are not dead systems, but active and evolving foundations of contemporary life.

Finally, the authors draw a line from Rome’s symbolic power to Italy’s current global image. Whether through luxury fashion brands like Armani or iconic automotive design like Ferrari, today’s Italian soft power is, in part, an extension of Rome’s legacy of prestige, refinement, and cultural sophistication.

Rome’s influence transcends history. It is embedded in the way we understand diplomacy, justice, war, and even lifestyle. The empire may have fallen, but its systems, symbols, and strategies continue to structure, the modern world.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: