Born in the Purple: Τhe Ιmperial Color of the Roman Empire

Purple, in the context of the Roman Empire, was not merely a color; it was a symbol of power, nobility, and divine sanction.

Throughout history, one color alone has held symbolic power and mystery: purple. Particularly in the context of the Roman Empire, purple was not merely a color; it was a symbol of power, nobility, and divine sanction.

The Origins of Purple

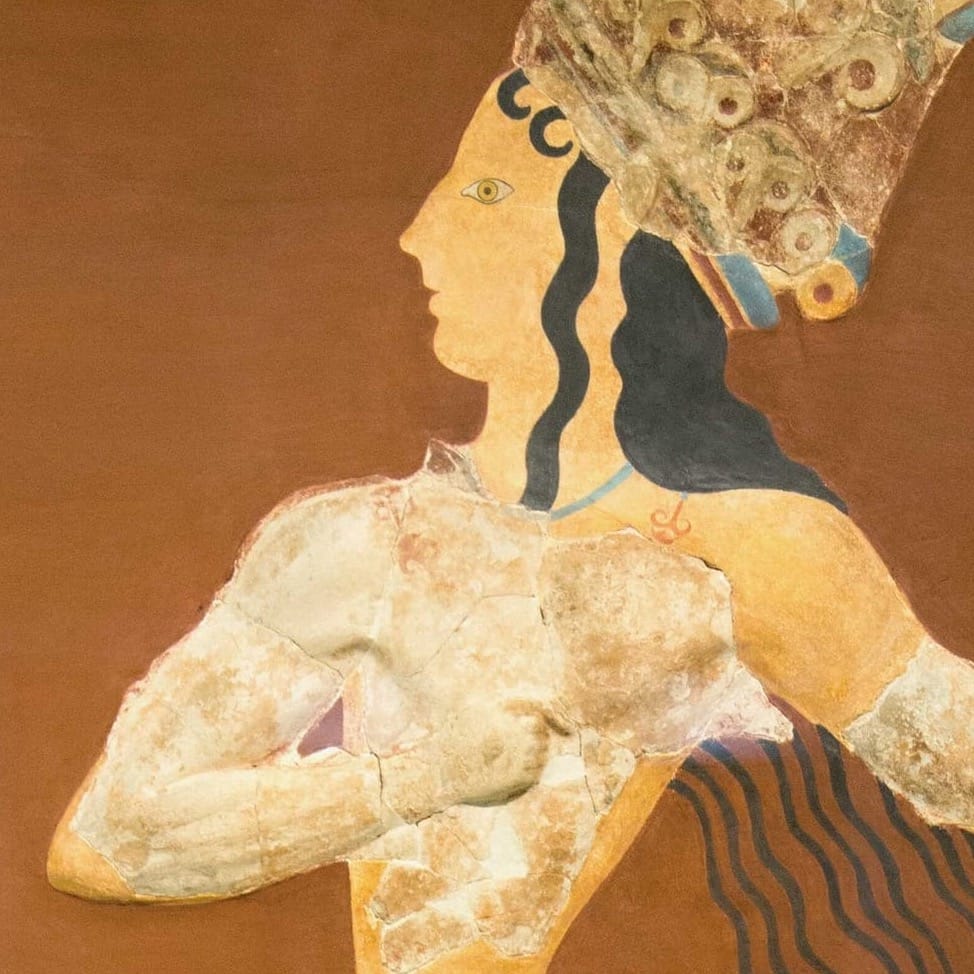

The earliest evidence of dye production appears to be at Kommos, possibly the port town of Phaistos, dating back to Middle Minoan IB/II (1925-1750 BC). By Middle Minoan II, dye production sites increased rapidly across Crete, including locations such as Kouphonisi, Palaikastro, and Pefka near Pacheia Ammos, all showing large deposits of crushed shells and signs of dyeing installations.

Palaces followed this trend, with evidence of shell deposits at Knossos, Zakros, and Mallia from the mid-millennium during Middle Minoan II-III. These production centers expanded during the Second Palace Period to other islands, including Kea, Thera, Aegina, and Chryssi.

Economically, this is understandable: Minoans, already engaged in long-distance trade with Eastern Mediterranean and Mesopotamian cultures, needed high-value exports to secure vital metals like tin and copper, as well as status goods.

Alongside evidence of sheep and textile production in Linear A, it is easy to envision that purple dye and luxurious dyed wool textiles became key exports for the Minoans, opening doors to international trade. Further supporting this is recent evidence from a royal tomb in Qatna, Syria, containing a thick layer of dye sediment and a small piece of partially murex-dyed tapestry, which may well have been Minoan in origin.

If this scenario is plausible, it is also clear that no monopoly on such a valuable product could last indefinitely.

Prince of the Lilies, Minoan fresco from Knossos, 1550 BC. Credits: Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0

By the middle of the Late Bronze Age, Near Eastern sites began producing their own dyes, with the earliest evidence appearing at Ugarit/Minet el Beidha around 1500 B.C., roughly corresponding to Late Minoan IB or later on Crete, marking the end of Minoan dominance. From that point until the widespread collapse of Bronze Age civilizations in the 12th century B.C., dyeing installations and shell deposits, indicating dye production, became more common across the Eastern Mediterranean.

It is likely that Crete initially managed to keep the secret of murex dye production, but after the Mycenaean takeover of Crete in the mid-15th century B.C., the monopoly was broken, leading to the broader spread of purple dye production. (The Color purple, by Carole Gillis)

What’s in Purple?

The color purple is often associated with an immeasurable, priceless luxury, almost belonging to a mythical realm alongside other rare goods. It is considered the ultimate symbol of social status and prestige. A key study on purple has highlighted its enduring desirability throughout the Greek and Roman world.

Roman literary sources provide substantial information about this color and its origins, with Pliny the Elder being the most frequently cited. In his Naturalis Historia, particularly in the chapter on sea animals, Pliny describes shellfish, including the purple snails, and offers a detailed account of how the purple dye was extracted and used for dyeing fabrics.

His description is the most comprehensive ancient explanation of the mollusc-purple dyeing process, forming the basis for modern dyeing experiments. However, Pliny’s primary interest was not in fabric dyeing but in describing marine creatures, with the purple dye being a notable characteristic of the sea snails.

Vitruvius, another Roman author, in his work De architectura, also discusses purple, though his focus is on pigments used in painting. Unlike Pliny, Vitruvius mentions a variety of terms for purple, indicating that different shades of the color were produced from various species of mollusks. (Purple and its Various Kinds in Documentary Papyri, by Ines Bogensperger, University of Vienna)

“We now turn to purple, which of all is most prized and has a most delightful colour excellent above all these.

It is obtained from sea shells which yield the purple dye, and inspires in students of nature as much wonder as any other material. For it does not yield the same colour everywhere, but is modified naturally by the course of the sun.

What is collected in Pontus and Gaul is black because these regions are nearest to the north. As we proceed between the north and west it becomes a leaden blue.

What is gathered in the equinoctial regions, east and west is of a violet colour. But in the southern regions it has a red character; for example, in Rhodes and other similar regions which are nearest the sun’s course.

When the shells have been collected, they are broken up with iron tools. Owing to these beatings a purple ooze like a liquid teardrop is collected by bruising in a mortar.

And because it is gathered from the fragments of sea shells it is called ostrum [Gk. ostreon = oyster]. On account of its saltness it soon dries unless it is mixed with honey.”

Vitruvius, De architectura

In ancient Greek, the term πορφύρα referred to both the murex shell and the purple dye, as well as textiles dyed with it. Another term for purple pigment was ὄστρεον (or ὄστρειον), which means oyster. Vitruvius referred to the purple dye made from Tyrian purple as ostrum.

In Latin, the standard word for purple was purpura, which, like its Greek predecessor, described not only the color but also murex shells, dyed fabrics, and social rank. A different Latin term, purpurissum, derived from the Greek πορφυρίζον, was used specifically to describe solid materials made from murex purple, particularly as a pigment or cosmetic.

There were several varieties of purple pigment, distinguished by their origins, such as Puteolan, Tyrian, Gaetulian, Laconian, and Canosan purple. These regional labels were not just a reflection of Pliny’s interest in geography, but were used in everyday life, as documented in papyri referring to purple dyes from Berenice and Tyre.

Pliny also noted that madder could be added to murex purple to create a pigment, and another additive was hysginum (ὕσγινον), made by mixing murex purple with kermes dye. The term hysginum may have originated from a Gallic word for the kermes insect (kokkos).

A question arises as to whether purpurissum could describe a purple pigment with only a small amount of true purple, potentially mixed with hysginum. This seems possible, given the wide price range for purpurissum (from one to thirty denarii per pound), which likely depended on factors like the amount of true purple used and whether it came from the strongest or weakest dip in the dyeing process.

However, it’s unlikely the term would apply to a pigment with no true purple at all. The Price Edict distinguishes between different types of purple-dyed wool, each with its own name and price, indicating that color names were still important and specific. (Pigment nomenclature in the ancient Near East, Greece, and Rome, by Hilary Becker)

How Was Purple Made?

Throughout antiquity, Murex snails (Murex trunculus) were used to create a highly prized purple dye that symbolized wealth, power, and social status. Numerous ancient texts discuss the production and demand for this dye, indicating that, while not universally appreciated, most Romans viewed it as a marker of luxury and political influence.

Archaeological findings further support the significance of the dye industry, particularly during the late Republican and early Imperial periods, when Rome saw an increase in agricultural and luxury imports. Murex snails were widespread across the Mediterranean, and various dye-producing installations have been discovered.

However, there has been no comprehensive study to categorize these facilities, and many archaeological sites have been incorrectly linked to the Murex industry, leading to distorted interpretations of ancient dye production, distribution, and consumption.

Our knowledge of murex dye largely stems from ancient sources, with Pliny’s account being particularly valuable due to the detailed information he provides. In his Natural History, Pliny explains the dyeing process, the value of purple dye, and price changes over the Roman era.

He describes how carnivorous snails were caught using baited baskets, and their shells were removed to extract the hypobranchial vein. This vein was soaked in salt for no more than three days. Pliny emphasized that while salting was necessary, it had to be done carefully, as fresher glands produced more vibrant dye.

The veins were then boiled in lead vessels over moderate heat, using a long funnel connected to the furnace. After a maximum of ten days, or when the desired shade was achieved, wool or other cloth was dipped in the dye and soaked for at least five days, depending on the mixtures used. Sunlight exposure was necessary to activate the dye’s color.

Pliny also described the range of purple hues that could be produced and their varying social and monetary value, with the dark "blood" purple from Tyre being the most prized. Several factors influenced the dye's final color, including boiling time, sunlight exposure, and additives like kermes or urine. As we explored in the beginning of our article, this dyeing technique had been perfected before Roman times, possibly by the Minoans or Tyrians, though its precise origins remain debated.

Regardless of where it began, the continued use of the dye from the Bronze Age onward highlights its enduring value. Romans associated purple dye with their cultural origins, and according to Pliny, its use in Rome dates back to Romulus, which sparked its popularity among other influential Romans.

“I see the use of purple always had been at Rome, but Romulus (was) in a mantle with purple stripes.

For by means of a toga praetexta and with a wide stripe, the enemy having been carried, it is agreed the first use was by the king, the Etruscans having been sufficiently defeated.

Nepos Cornelius, who by means of the divine Augustan rule, left behind: Me, he said, with youth the vigorous purple thrived.”

Pliny the Elder

It is unclear whether those who wore murex-dyed garments actually favored the color itself. Nevertheless, they greatly valued the dye due to its recognized worth, which was widely acknowledged in Rome. Pliny sheds light on this:

“To these, the bundles of rods and hatchets of Rome made the way, and the same was for the majesty of childhood and distinguished the senator from the knight, it was called for appeasing the god, and illuminating every cloth, in triumph mixed with gold.”

The purple hue was valued not for its aesthetic appeal but because it allowed certain social ranks to be easily recognized and symbolized the high monetary cost of its production. The dye became a hallmark of aristocratic attire, visually distinguishing the elite from the lower classes.

One example Pliny mentions is the toga praetexta, a white wool toga with a purple border and red sleeves, worn by senators. The toga picta, entirely purple with gold embellishments, symbolized Jupiter Optimus Maximus and was first worn by Julius Caesar, later reserved for emperors on special occasions.

The dye wasn't limited to government and religious garments; over time, influential groups were allowed to wear small stripes of purple, especially as the Empire aged and declined. The key point is that the dye’s popularity was not tied to the color itself, but to the social and economic significance of wearing purple-dyed cloth. Romans were not passionate about the color purple itself, but rather the symbolism it carried.

Other ancient writers also mention the dye. In his Geography, Strabo notes that purple dye was available as far as Sicily and specifically comments on the high quality of the dye produced in Tyre.

“The shell-fish are caught near the coast; and the other things requisite for dyeing are easily got; and although the great number of dye-works makes the city unpleasant to live in, yet makes the city rich through superior skill of its inhabitants”.

Vitruvius explains that the various shades of purple described by Pliny were influenced by the region where the dye was produced. The eastern and western parts of the Mediterranean yielded the deepest purple hues, while the southern regions produced a more reddish tint.

“However that was removed out of the marine (spiral) mollusk, from which purple is made, that there are not less of marvels than the others of nature for the people considering, because it has not in all places, at which it is born, tempered naturally by the course of the sun.

Therefore because it was chosen in the Pontis and at Gallia, because these regions are closest to the north, it is very dark. By those going forth between the north and the west, a blueish purple was found.

However because that which is collected for those going towards the east and west orient, is found with a violet color; that which is snatched up from the southern regions and is created with red potency, and to such an extent was created at the island of Rhodes furthermore and at other regions of this type which are closest to the path of the sun.”

It is apparent that the writings of Pliny, Strabo, and Vitruvius illustrate that the different hues produced by murex snails were associated with social status in Roman society, and these dyes had been in use since the founding of Rome. (The Roman―Frantic Passion for Purple. A Geographic Analysis of the Murex Dye Industry from the late Roman Republican Period to Late Empire, by Natalie M. Susmann)

The Symbolism of Purple in Rome, and the Laws Surrounding it

In reality, purpura (purple dye) served as a highly versatile and sophisticated symbol for perception and recognition. By the late Republic, there is some evidence that people could discern one's political leanings based on the shade of purple worn on the senatorial toga praetexta.

Lighter, reddish shades of purple were linked with popularis politics, while darker shades were associated with optimate politics. A particular genus of purple, likely a lighter, redder shade, was even seen as a sign of political immaturity and radicalism.

Plutarch also notes that the Younger Cato, disturbed by an excessively red and sharp shade of purple, made a point of wearing the darkest possible hue. Purple had become so ingrained in Roman politics that a discriminatory vocabulary arose, distinguishing between light and dark purples, Tyrian purples, and those produced in Italy, Sicily, or Greece, as well as double-dyed varieties. The color-fast properties of the dye even led to an association with cleanliness, as those wearing purple could wash their clothes frequently without losing color.

Beyond the fishy origins that Pliny emphasized, Romans could derive rich social and political information from how purpura was worn by both men and women. The status of purpura as the epitome of luxury derived from its association with Lydian, Persian, and Hellenistic royal attire, as well as Etruscan iconography.

The lex Oppia (The Lex Oppia was a law established in ancient Rome in 215 BC) debate shows how widespread the use of purple was, worn not only by Roman senators but also by low-ranking magistrates, priests, boys, women, and Latin allies. Polybius records that purpura was carefully regulated at Roman funerals, with specific garments like the toga praetexta, toga purpurea, and toga picta each having their own symbolic meaning.

However, the political instability of the late Republic blurred these once-clear distinctions, and the use of purpura outside of formal political contexts could signal autocratic aspirations or anti-establishment leanings. Excessive use by women was also viewed with suspicion.

The social and political meanings of purpura evolved alongside developments in the late Republic and early Empire, making the dye increasingly contentious and a source of controversy and misunderstanding. Purpura’s power was so great that Caesar enacted laws restricting the wearing of sea-purple clothes to certain days, while Dio claims that Octavian limited the use of purple garments to senators holding magistracies. Around the same time, Antony granted members of the Hieroneikai in Ephesus the exclusive right to wear purple on special festival days.

Political legislation by the Julio-Claudian emperors also sought to regulate the use of purpura, limiting it to certain individuals and occasions. In the early Empire, four forces were at play: the longstanding use of purple as a status symbol, its role as a badge of official Roman positions, growing nationalist critiques of luxury (luxuria), and attempts to institutionalize its use for official Roman roles.

Under Augustus, purpura became a foil to the simplicity and moderation associated with the new regime. Augustan poetry also exploited the color to evoke prosperity and imperial abundance. However, excessive emphasis on purpura as an ethical or political symbol became a familiar target in Augustan literature, as illustrated by Augustus himself, who humorously mocked the cultural obsession with the color in Macrobius’ Saturnalia.

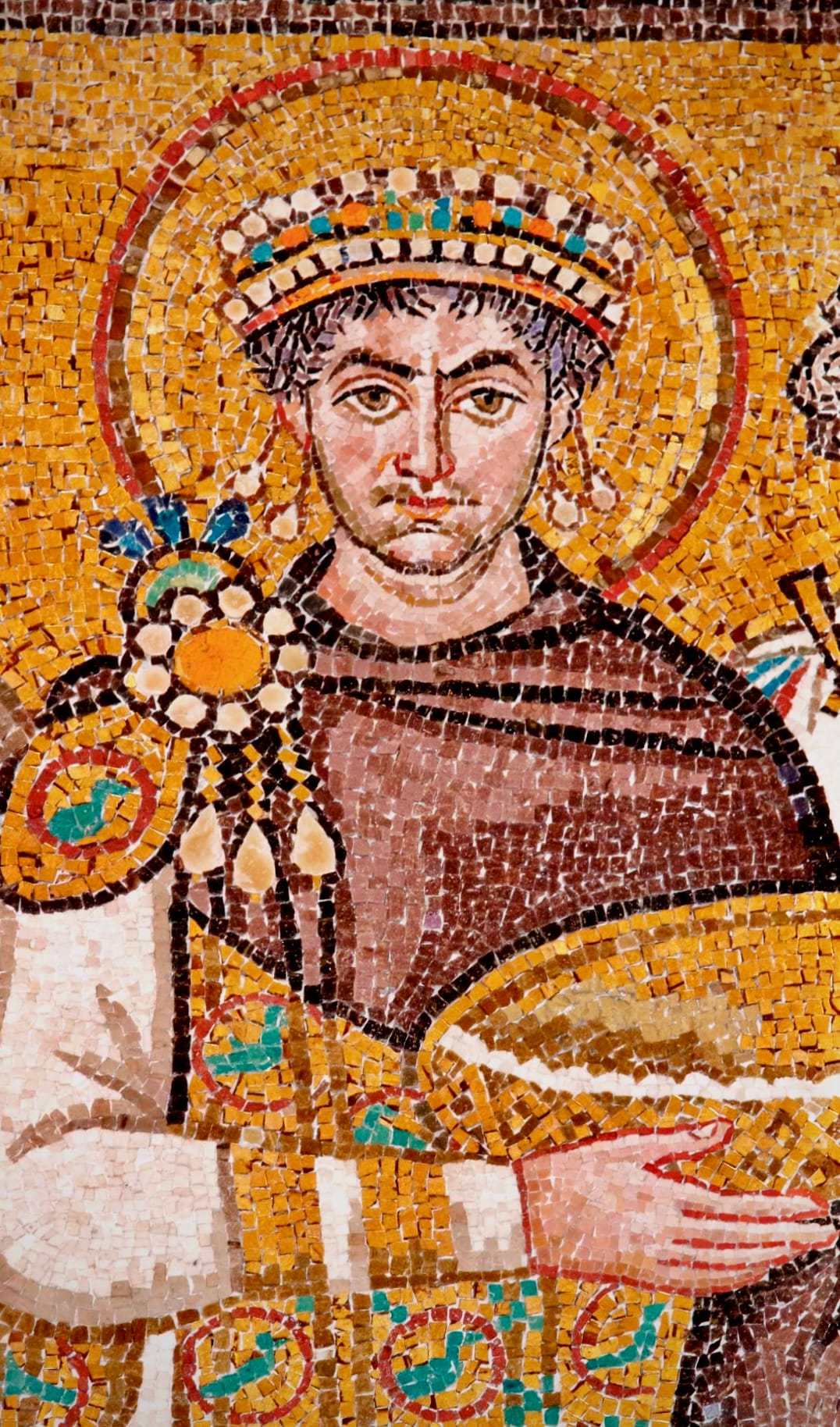

Over the centuries, the Roman state took extraordinary measures to monopolize the production of purple dye, dedicating its use exclusively to the emperor. In the Byzantine Empire, purple signified imperial monopoly. It was also used for important imperial documents, marking those adorned with it as high-ranking officials or bishops.

A mere spot of purple on one’s clothing signified a direct connection to imperial power or the church hierarchy.

Christ's face (close), Deësis mosaic, Hagia Sophia. Credits: profzucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Thus, the phrase "born in the purple" came to denote those of noble birth, specifically those born in the imperial family, highlighting the color's deep ties to power and lineage.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: