“Ave Imperator, morituri te salutant”. What did Gladiators actually say before fighting?

The phrase Hail Emperor, those who are about to die, salute you, was not actually used by the gladiators.

The phrase "Ave Imperator, morituri te salutant" translates to "Hail, Emperor, those who are about to die salute you." It is famously associated with gladiators in Ancient Rome, who are believed to have addressed the Roman Emperor with this phrase before commencing combat in the arena. However, the historical accuracy and origin of the phrase are subjects of scholarly debate.

When did “Those we are about to die salute you” appear for the first time?

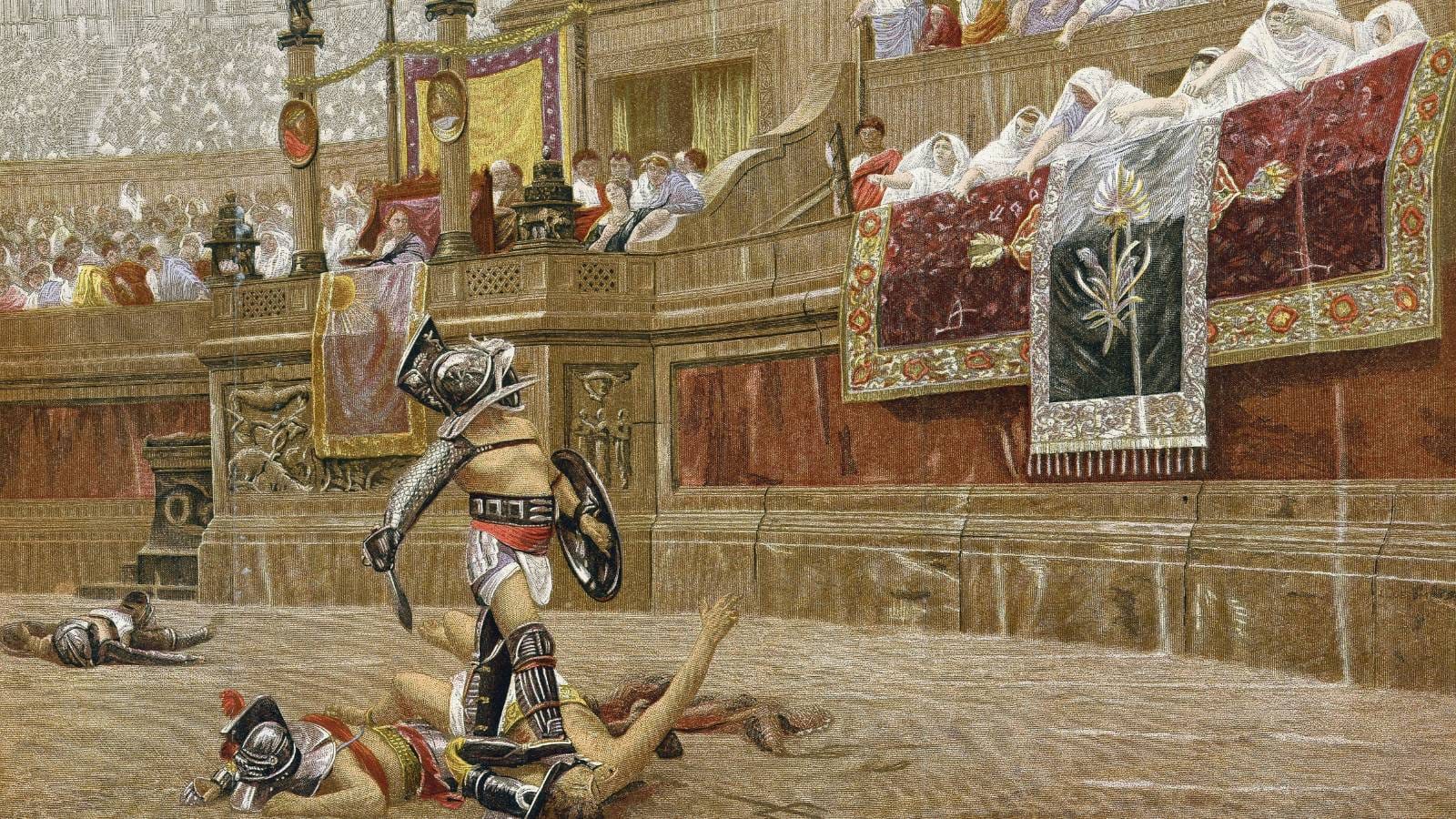

Among the practices of the ancient Romans, the colorful salute of the gladiators is particularly celebrated. As they entered the arena in procession, accompanied by music, the burly fighters would march towards the emperor's box. According to Carcopino's book, La vie quotidienne à Rome, "they turned toward the prince and, with right arm extended in his direction as a mark of homage, addressed to him that mournful, prophetic salute, Ave imperator, morituri te salutant."

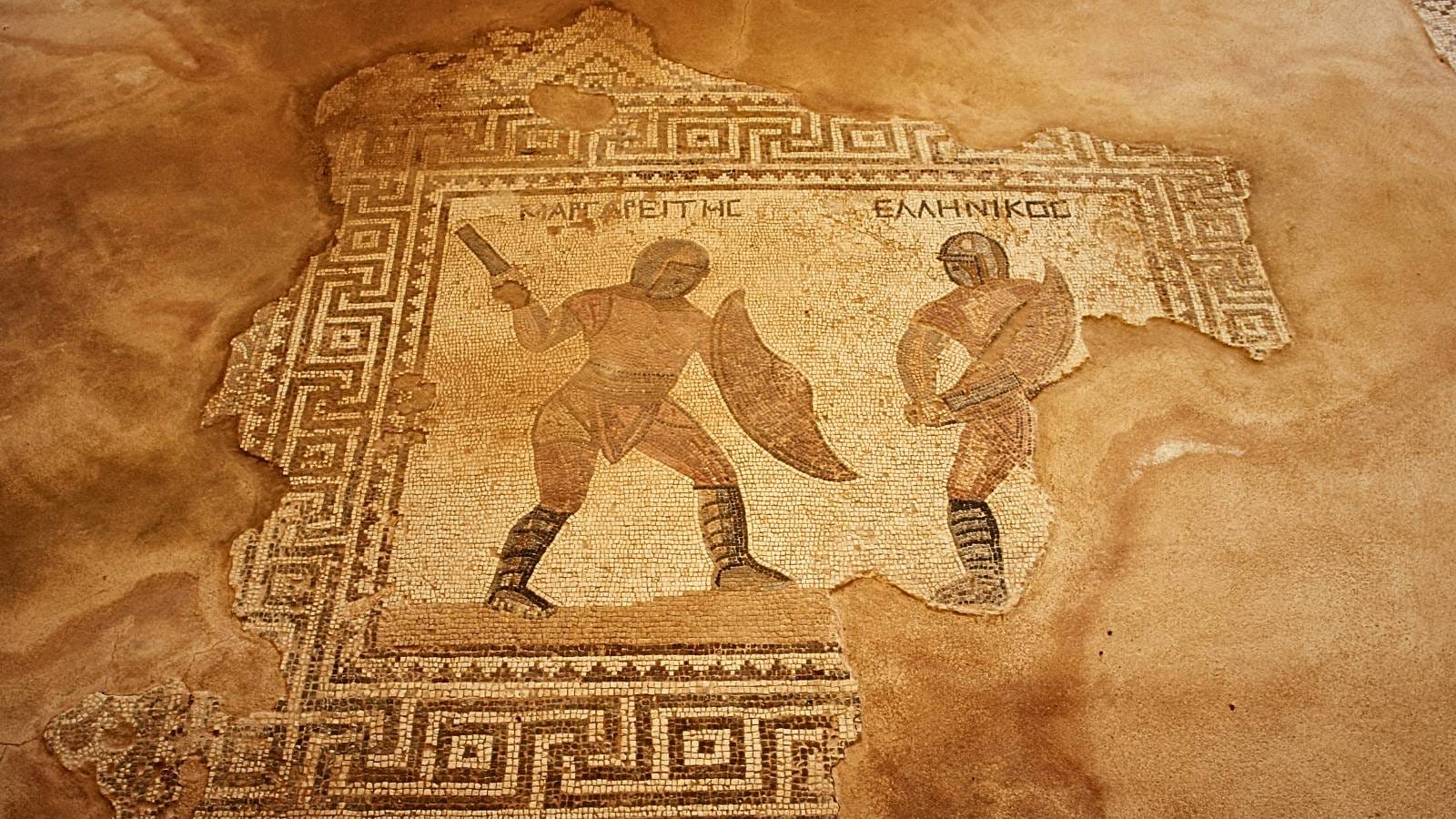

With slight variations in detail, this ritual is described in numerous works on Roman antiquities, making it one of the best-known and most frequently cited Roman customs. Some accounts depict each gladiator stopping to have his weapons examined by the editor of the games before raising his right arm and delivering the salute. Typically, the salute is quoted with the verb in the first person, salutamus, rather than the third-person form, salutant.

The phrase is recorded in the writings of Suetonius, a Roman historian. In his work "De Vita Caesarum" (Life of the Caesars), Suetonius recounts an event where captives participating in a mock naval battle (naumachia) during the reign of Emperor Claudius (41-54 AD) supposedly greeted the emperor with these words.

In AD 52, Emperor Claudius constructed an underground channel to drain the waters of Lake Fucinus in the central Apennines, aiming to protect the surrounding area from floods and reclaim the land for agriculture. Suetonius records that before draining the lake, Claudius organized a naval battle there.

When the fighters shouted "Ave imperator, morituri te salutant," Claudius responded with "Aut non," implying he had pardoned them, leading the fighters to refuse to engage. Suetonius continues, describing how Claudius, in a tantrum, threatened to destroy them all with fire and sword, jumped from his seat, dashed around the lake, and alternated between shouting threats and begging them to fight. Cassius Dio, writing a century later, also describes this event, using the Greek verb in the first-person plural for the fighters' words. (H. J. Leon, MORITURI TE SALUTAMUS, The University of Texas)

“He gave representations in the Campus Martius of the storming and sacking of a town in the manner of real warfare, as well as of the surrender of the kings of the Britons, and presided clad in a general's cloak. Even when he was on the point of letting out the water from Lake Fucinus he gave a sham sea-fight first.

But when the combatants cried out: "Hail, emperor, they who are about to die salute thee," he replied, "Or not," and after that all of them refused to fight, maintaining that they had been pardoned. Upon this he hesitated for some time about destroying them all with fire and sword, but at last leaping from his throne and running along the edge of the lake with his ridiculous tottering gait, he induced them to fight, partly by threats and partly by promises.

At this performance a Sicilian and a Rhodian fleet engaged, each numbering twelve triremes, and the signal was sounded on a horn by a silver Triton, which was raised from the middle of the lake by a mechanical device.”

Suetonius, The Lives of the Caesars

“Claudius planned to stage a naval battle on a particular lake. He constructed a wooden wall around it, set up stands, and gathered a massive crowd. Claudius and Nero were dressed in military attire, while Agrippina wore a beautiful chlamys woven with gold threads, and the rest of the spectators dressed as they pleased.

The participants in the sea battle were condemned criminals, with each side consisting of fifty ships, one group named "Rhodians" and the other "Sicilians." Initially, they assembled and collectively addressed Claudius, saying, "Hail, Emperor! We who are about to die salute thee."

When this plea failed to save them, and they were still ordered to fight, they maneuvered through their opponents' lines, causing minimal harm to each other. This continued until they were compelled to engage in genuine combat and destroy one another.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History

The Naval Battles of Gladiators

Apart from these two passages that refer to the same incident, there are no other ancient references to a gladiatorial salute. Moreover, in this instance, the salute was not given by gladiators but by naumachiarii, the fighters in a naumachia, or staged naval battle. The naumachia, (Greek: ναυμαχία) also known by the Romans as navalia proelia, was a large-scale and bloody spectacle involving combat on multiple ships, held on large lakes or flooded arenas.

Prisoners of war and criminals sentenced to death were forced to participate in these naval battles for public entertainment. The individuals chosen for these events were called naumachiarii. The first known exhibition of this kind was organized by Julius Caesar in 46 B.C. during his triumphal games, held in an artificial lake constructed for this purpose in the Campus Martius near the Tiber.

Subsequent naumachiae were staged on special occasions, notably by Augustus in 2 B.C., by Claudius in the previously mentioned event, twice by Nero, and by Titus and Domitian. Later emperors may have occasionally held such spectacles, although no definite references exist after Domitian. Augustus created a large lake across the Tiber for his naumachiae, which was later reused. Titus and Domitian flooded the Colosseum for these events, and Domitian also dug a new lake near the Tiber.

Naumachiae typically depicted significant historical naval battles with gruesome and bloody realism. For instance, Caesar, employing four thousand oarsmen and two thousand fighters, reenacted a battle between the Tyrians and Egyptians, with participants dressed in the attire of those nations. Augustus had three thousand fighters, representing Athenians and Persians, reenact the battle of Salamis.

In the Lake Fucinus event we described above, Claudius used nineteen thousand men to stage a battle between Sicilians and Rhodians, with fifty large warships on each side. Under Titus, three thousand men dramatized the famous sea battle between the Athenians and the Syracusans. On another occasion, Titus represented a battle between Corcyreans and Corinthians in the flooded Colosseum.

Analysing the history of “Those who are about to die salute you”

Returning to our phrase, Dio, in his account of the event, clearly states that the fighters were criminals condemned to die. Tacitus further informs us that to prevent the escape of the nineteen thousand desperate men, the central portion of the lake was entirely encircled by a ring of rafts or floats, manned by elite soldiers of the Praetorian Guard, both infantry and cavalry.

These soldiers were protected by ramparts, equipped with catapults and ballistae, and reinforced by ships carrying marines ready for combat. Tacitus also notes that although the fighters were criminals (sontes), they fought with the bravery of courageous men and, after much bloodshed, were excused from the slaughter. His use of the word occidioni, in relation to the status and character of the men, suggests that total extermination of the combatants was expected but they were spared due to their bravery.

While Tacitus does not mention the salute, Dio states that before the fight began, the combatants gathered and saluted the Emperor (using the Greek equivalent of the words quoted by Suetonius, except for the verb form). When they realized that this appeal did not save them and they were still required to fight, they initially tried to inflict as few wounds as possible.

At the end, they were compelled to kill each other in earnest.

Image credits: Photos.com by Canva

“About the same time, the mountain between Lake Fucinus and the river Liris was bored through, and that this grand work might be seen by a multitude of visitors, preparations were made for a naval battle on the lake, just as formerly Augustus exhibited such a spectacle, in a basin he had made on this side the Tiber, though with light vessels, and on a smaller scale.

Claudius equipped galleys with three and four banks of oars, and nineteen thousand men; he lined the circumference of the lake with rafts, that there might be no means of escape at various points, but he still left full space for the strength of the crews, the skill of the pilots, the impact of the vessels, and the usual operations of a sea-fight.

On the raft stood companies of the praetorian cohorts and cavalry, with a breastwork in front of them, from which catapults and balistas might be worked. The rest of the lake was occupied by marines on decked vessels. An immense multitude from the neighbouring towns, others from Rome itself, eager to see the sight or to show respect to the emperor, crowded the banks, the hills, and mountain tops, which thus resembled a theatre.

The emperor, with Agrippina seated near him, presided; he wore a splendid military cloak, she, a mantle of cloth of gold. A battle was fought with all the courage of brave men, though it was between condemned criminals. After much bloodshed they were released from the necessity of mutual slaughter.”

Tacitus, Annals

Combining the three, Saetonius, Cassius Dio and Tacitus, we can reasonably infer that these condemned convicts addressed Claudius with their "morituri te salutant" as an appeal, hoping to gain the Emperor's sympathy, rather than as a regular and formal salute. When Claudius responded with "Aut non," they interpreted it as "aut non morituri," indicating a pardon—Suetonius notes it was "quasi venia data" (as if pardon were given)—and initially refused to fight.

However, they eventually yielded either to the Emperor's pleas or to coercion and fought bravely until the survivors were excused from further slaughter.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: