Ascending to the Divine: The Practice and Meaning of Apotheosis in Ancient Rome

How was apotheosis used as a religious practice, but also as a political tool in ancient Rome? How was it used to solidify dynastic legitimacy and reinforce imperial ideology?

Apotheosis, derived from the Greek term ἀποθεώσις, refers to the elevation of a mortal to divine status. While Greek mythology offers numerous examples of mortals becoming deities, such deification was rare in republican Greece.

Exceptions include the people of Amphipolis honoring Brasidas posthumously and the residents of Egeste venerating Philippus for his beauty. In the Hellenistic period, rulers often granted divine honors to predecessors, as described by Theocritus in relation to Ptolemy of Egypt.

Apotheosis in the Roman Empire

Among the Romans, apotheosis specifically referred to the posthumous deification of emperors, a practice known as consecratio. Rooted in the Roman belief that the souls (manes) of ancestors became divine, this tradition often portrayed deceased emperors as the "fathers of the country."

Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome, was said to have been deified as Quirinus, though no other kings or republic figures were similarly honored. Julius Caesar was the first Roman to receive apotheosis, with Augustus institutionalizing games in his honor, setting a precedent followed for subsequent emperors.

The ritual of apotheosis, as detailed by Herodian, involved elaborate ceremonies blending mourning and celebration. A wax effigy of the deceased emperor was displayed on a golden couch in the palace, surrounded by senators and noblewomen in mourning attire. After seven days of symbolic "deterioration," the image was carried through the Via Sacra to the Campus Martius.

There, a multi-tiered wooden pyre, resembling a lighthouse, was built and filled with aromatic substances. The structure was set ablaze, and an eagle was released from the top to symbolize the emperor's soul ascending to join the gods. This act was often commemorated on coins bearing the word Consecratio and images of an eagle rising from an altar.

Medals and artifacts from Julius Caesar to Constantine the Great often depict these apotheosis rituals, reflecting the tradition's enduring significance in Roman society and its intertwining of political and religious ideologies. (Apotheosis, by William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875)

Roman Apotheosis: Cicero, Ennius, and the Immortalization of Heroes

Cicero’s De Re Publica and the works of Ennius offer profound insights into the concept of apotheosis, blending mythological narratives, historical precedents, and political philosophy. Apotheosis, the elevation of mortals to divine status, was not merely a religious phenomenon; for Cicero, it was a vehicle to inspire moral reform, celebrate virtue, and sustain the Republic.

Apotheosis as a Cultural Tradition

Cicero draws heavily from Ennius’s Annales, which vividly describes the apotheosis of Romulus. During a solar eclipse, Romulus is envisioned ascending to the heavens, a poetic image immortalized by Ennius in the phrase, "Romulus spends eternity in the sky with the gods."

This powerful line provides Cicero with a cultural anchor, situating apotheosis as a revered tradition within Rome’s history.

Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius and his wife Faustina The Elder Apotheosis. Credits: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Cicero builds on this tradition to argue that heroism and selfless service to the state warrant divine recognition. For him, apotheosis was deeply tied to Roman identity and the virtues that built the Republic. Quoting Ennius, he laments the erosion of these foundational values, declaring, "The Roman state stands upon the morals and men of old." Cicero's words highlight a profound nostalgia for the principles of courage, justice, and civic duty, which he believed were essential for Rome's survival.

Apotheosis as a Political and Philosophical Tool

In Cicero’s political philosophy, apotheosis was not just a mythological notion but a moral and civic reward for exceptional leadership. He emphasizes that divine honors should be reserved for those whose virtues have significantly benefited the Republic.

Using Romulus as an example, Cicero celebrates the founder of Rome as a model of apotheosis, stating that Romulus’s ascent to divinity was a testament to his role in creating and securing the Roman state. Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis (Dream of Scipio) further illustrates his philosophical approach to apotheosis.

In this celestial vision, Cicero describes a specific place in the heavens reserved for those who save or elevate the fatherland, where they "may enjoy eternity in blessedness." By linking the heroic deeds of Rome’s leaders to a cosmic order, Cicero elevates their contributions to a divine scale, reinforcing the notion that civic virtue has eternal rewards.

Apotheosis and the Critique of Contemporary Rome

Cicero uses the concept of apotheosis to critique the moral and political decline of his own time. He contrasts the virtues of past heroes with the corruption of his contemporaries, lamenting that "the morals of antiquity are not only not cherished but are now unknown."

For Cicero, the survival of the Republic depended on reviving these ideals and honoring the legacy of Rome’s great figures through apotheosis.

The dream of Scipio as portayed by Cicero, of Roman heroes welcomed in Heaven. Illustration: Midjourney

His critique also extends to the broader Roman populace, whose failure to uphold the values of their ancestors endangered the state’s stability. By invoking the moral greatness of figures like Romulus, Cicero sought to inspire his fellow citizens to emulate their virtues and restore Rome’s moral compass.

The Broader Significance of Apotheosis

Through apotheosis, Cicero links Rome’s mythical past to its political present, using the concept to celebrate exemplary leadership and inspire civic virtue. The phrase from Ennius, "Romulus spends eternity in the sky with the gods," serves as a cultural touchstone, while Cicero’s philosophical reflections, such as "For all those who have saved, aided, or increased the fatherland, there is a specific place set aside in the sky," elevate apotheosis to a moral ideal.

Ultimately, Cicero transforms apotheosis from a mere religious rite into a profound commentary on leadership and virtue. It becomes a symbol of the Republic’s highest aspirations, immortalizing those who embody the principles that made Rome great.

For Cicero, the apotheosis of Rome’s heroes was not just about honoring the past but about guiding the future—a call to restore the moral integrity of the state and its people. (Cicero, Ennius, and the Concept of Apotheosis at Rome, by Spencer Cole)

Ascending to Divinity: The Complex Rituals of Imperial Apotheosis in Ancient Rome

The deification of Roman emperors was a fascinating blend of religious practice, political strategy, and ceremonial spectacle that evolved over centuries. Rooted in earlier traditions of venerating exceptional individuals, the practice reflected the intricate dynamics of Roman society.

Apotheosis became a way to honor emperors, legitimize successors, and project the divine authority of the state. In its early phases, apotheosis drew from Roman customs where veneration of ancestors often elevated remarkable figures to divine status.

Julius Caesar’s deification marked a turning point. As the first Roman to be declared a state god during his life, Caesar’s apotheosis set a precedent fraught with both reverence and controversy. His tragic demise demonstrated that the concept of divinity could be a powerful tool for securing social prestige, but also a dangerous political gamble. It was said:

“His tragic demise showed to all his successors that the divinity, albeit a mighty tool in gaining social prestige, was a strong card not to be played lightly.”

The practice became more formalized under Augustus, who carefully balanced his mortal and divine status. While alive, Augustus refrained from overt claims to divinity, preferring to embody a semi-divine aura. After his death in 14 CE, the Senate officially deified him, and Emperor Tiberius consecrated him as a god.

The symbolic release of an eagle from his funeral pyre was central to the ceremony, signifying his soul’s ascent to the heavens. As Augustus himself had claimed during his reign, “Have I played my part well? Then applaud as I exit.” These rituals set a precedent for subsequent emperors, intertwining apotheosis with state governance and religious devotion.

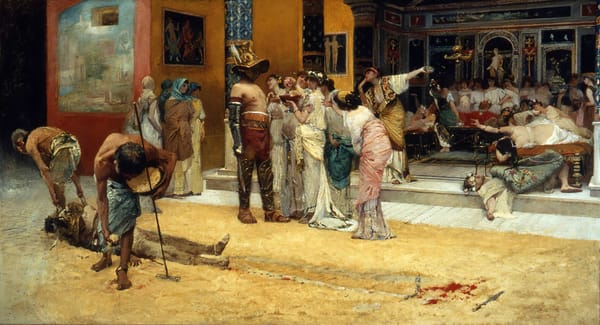

By the time of the Antonine emperors, apotheosis had become a well-established tradition, marked by elaborate public ceremonies and institutionalized practices. A significant innovation during this period was the double funeral: one for private burial and another involving the cremation of a wax effigy. This duality served both practical and symbolic purposes, ensuring that the emperor’s mortal remains could be handled discreetly while the public witnessed the divine transformation.

The ritual reached its climactic moment with the release of an eagle from the pyre, (as already mentioned above) symbolizing the emperor’s soul ascending to the gods. Observers remarked that “the apotheosis of the dead emperor began to be symbolically performed by the release of an eagle from the pyre, observable to all participants in the funeral.”

The spectacle of apotheosis highlighted the emperor’s transition from human ruler to a divine being, while also reinforcing the unity of the Roman state. The Senate’s role in approving deification and the participation of the succeeding emperor ensured the practice was deeply tied to political stability. As one observer noted, “From the end of the second century CE, deification became a matter of convention… What was important was a senatorial decree and steps taken by new emperors who usually wished to deify their predecessors.”

Apotheosis, therefore, was not merely a religious act but a profound expression of Rome’s political and cultural ideology.

A possible representation of an eagle being released from the pyre of a Roman Emperor during his apotheosis ritual. Illustration: Midjourney

It celebrated the emperor’s virtues, reinforced the legitimacy of their successors, and projected an image of eternal imperial authority. Through elaborate rituals, symbolic gestures like the eagle’s flight, and the careful crafting of public narratives, Rome transformed its leaders into enduring figures of divine power and ensured that their memory would resonate for generations. (How Did Roman Emperors Become Gods? Various Concepts of Imperial Apotheosis, by Aleš Chalupa)

Augustus and the Concept of Apotheosis

The concept of apotheosis, played a central role in Augustus’ reign, intertwining his political achievements with a broader cultural and religious framework. By adopting and adapting Hellenistic traditions of ruler cults, Augustus crafted a legacy that seamlessly connected his mortal deeds to divine recognition, shaping how Romans viewed imperial power and divinity.

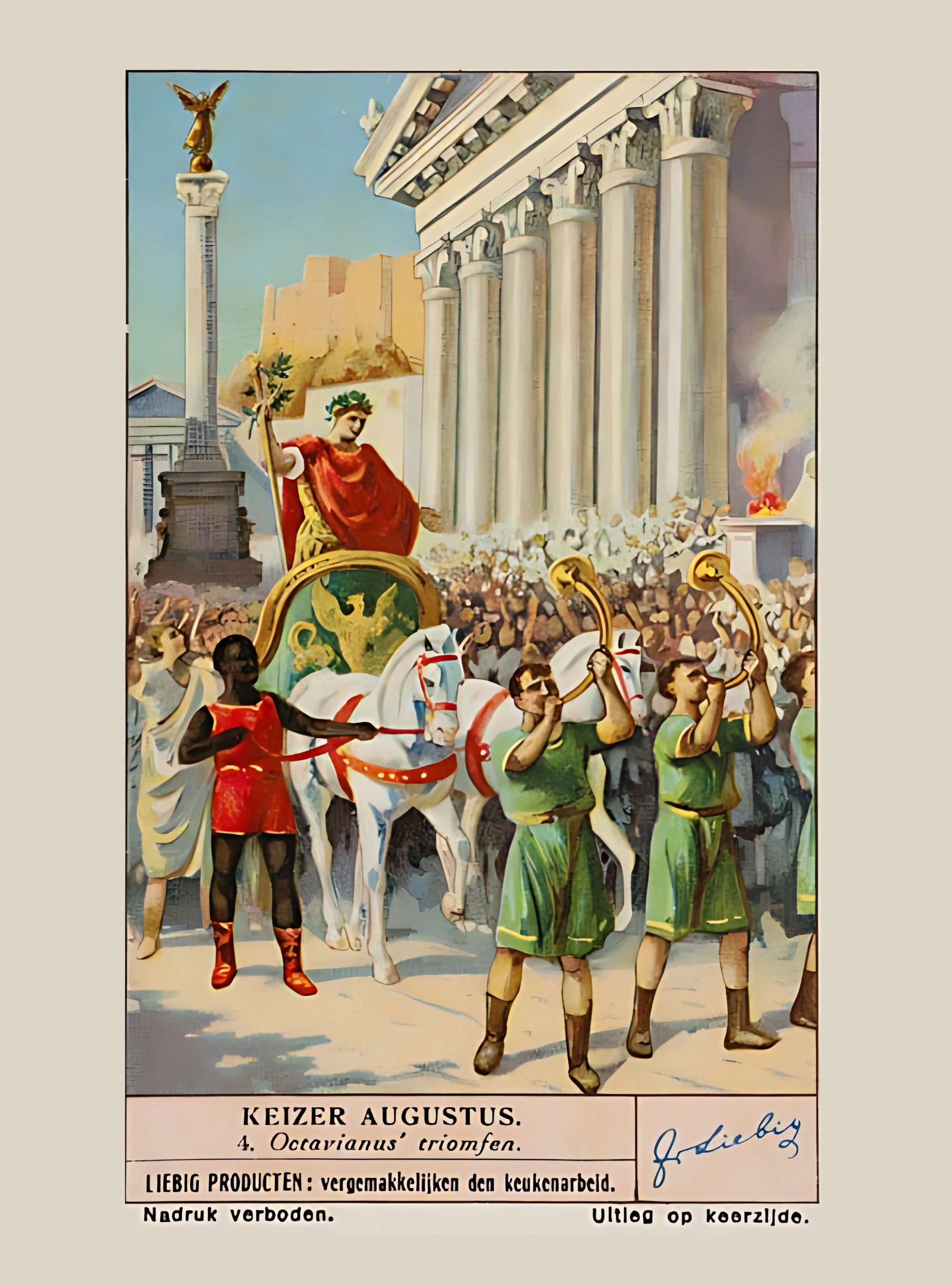

Drawing inspiration from the Hellenistic world, Augustus modeled his image on figures like Alexander the Great, who had been deified for their conquests and benefactions. Augustus’ triumphs, from his military victories to his role as a benefactor of the Roman people, were framed as evidence of his divine worthiness. His achievements were reinforced through literature, public ceremonies, and monumental architecture, all of which linked his mortal actions to divine favor.

In Virgil’s Aeneid, for example, Augustus’ ascent is prophesied in the words of Anchises and Jupiter, who speak of his role as a bringer of peace and a conqueror of the world. The imagery suggests Augustus would ascend to the heavens, “laden with the spoils of the East,” echoing the divinization of past Hellenistic rulers.

The Res Gestae, Augustus’ autobiographical account of his accomplishments, solidifies this connection. It mirrors the language and ideals of Hellenistic apotheosis, where rulers were elevated for their contributions to the welfare of their people.

Augustus presents himself as a model for future generations, emphasizing his diplomatic victories, moral reforms, and dedication to Rome’s prosperity. The recovery of Crassus’ standards from Parthia, a major diplomatic success, is portrayed as a symbol of his divine mandate and ability to restore Roman honor.

Public rituals and symbols further enhanced Augustus’ association with divinity. His triple triumph in 29 BCE not only celebrated his military successes but also drew parallels to Hercules, a mortal who ascended to godhood through his labors. Monuments, coins, and statues depicted Augustus alongside Jupiter, Apollo, and other gods, visually reinforcing his semi-divine status. This imagery was not accidental but part of a carefully orchestrated narrative to cement his apotheosis in the Roman consciousness.

The role of literature was pivotal in embedding Augustus’ divine narrative. Poets like Virgil, Horace, and Ovid celebrated Augustus’ deeds, using mythological references to align him with gods and heroes. Virgil, in particular, positions Augustus as surpassing Dionysus’ eastern conquests and equaling the labors of Hercules. Such literary portrayals were instrumental in shaping public perception, blending historical reality with divine myth.

Augustus’ apotheosis reflects a broader cultural shift in Roman religious and political thought. By drawing on both Roman traditions and Hellenistic models, Augustus redefined the relationship between ruler and divine, ensuring that his legacy extended beyond his mortal life. His ability to align conquest, benefaction, and divine favor into a unified narrative established him not only as Rome’s foremost leader but also as a figure worthy of divine veneration.

This legacy, carefully constructed during his lifetime, ensured that Augustus would be remembered as the quintessential example of mortal achievement and divine ascension. (Augustus, the Res Gestae and Hellenistic Theories of Apotheosis, by Brian Bosworth, The Journal of Roman Studies)

A Soul is Divine by Nature

The Orphic tradition, which profoundly influenced thinkers from Euripides to Aristotle, presented the belief that the human soul is inherently divine. This divinity is not something gained at death but an eternal state, temporarily obscured by life in the physical body. At death, the soul simply returns to its divine condition.

The Orphic precept, “Already thou art a God: seek to be united with the gods,” encapsulates this belief. Aristotle echoes this idea when he states, “Strive to become immortal”, suggesting that apotheosis reflects the soul’s return to its original divine state—a restitutio in pristinum statum, or restoration to its former condition.

This Orphic notion of the soul’s return to divinity resonated deeply and widely, as explored in detail by Rohde in Psyche. It shaped the cultural and theological frameworks of Greek and Roman societies, making the deification of figures like Alexander the Great more comprehensible. To his contemporaries, Alexander, proclaimed as Zeus Ammon incarnate, was not merely a mortal ascending to godhood but a divine being reclaiming his rightful place.

The very term apotheosis thus carried profound theological implications rooted in this cycle of divinity.

An Ancient Etruscan Amphorae depicting Heracles’ Apotheosis, by Micali. Heracles on the far left holding his club, next to him possibly Athena. Poseidon, Hera and Zeus in the middle, Ares and Aphrodite on the right. Credits: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Similarly, Roman emperors who underwent deification were seen by some not merely as new gods in Olympus but as returning to their original divine essence. Julius Caesar, for instance, was revered as Iuppiter Iulius, while Livia was equated with Ceres, and Hadrian became associated with Jupiter.

The term apotheosis itself evolved to embody these layered meanings. For the masses, it often symbolized the elevation of a mortal to divine status. However, for others, it signified a more profound theological return—a restoration of an incarnated deity to their original divine state. This understanding extended beyond emperors and exceptional figures like Caesar and Alexander.

By the Roman period, even the burial of an ordinary citizen could be described using the term apotheosis, reflecting the belief that all souls returned to their divine origins. In this context, the ceremonial consecration of an emperor like Antoninus Pius, who referred to himself as the world’s master, shared a fundamental similarity with the interment of the humblest individual.

This broader theological context sheds light on the fourth-century poet Prudentius, who titled his polemic poem Apotheosis. The work was not an example of decadent affectation or heretical ambiguity, as some have suggested. Instead, it fiercely opposed heretical interpretations by affirming that apotheosis meant the return of the soul to its divine parent, or parens Deitas.

As Prudentius declares in the poem, it is the resumption of what had always been inherently divine. This conception underscores the enduring influence of Orphic thought on Roman religious and cultural practices, from the glorification of emperors to the spiritual understanding of human mortality.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: