Acta Diurna: How Rome Made News Public

Some societies spoke their news aloud. Others fixed it in place, allowing it to be encountered, consulted, and remembered. In Rome, public information followed a path shaped by visibility, authority, and daily life.

Long before information was gathered, edited, and delivered as a product, Rome developed its own way of shaping what people knew about the world around them. Certain events were meant to be seen rather than heard, fixed rather than fleeting, and encountered as part of daily movement through the city. These public traces did more than inform. They structured attention, directed conversation, and quietly reinforced authority by deciding what deserved to be visible at all.

When Knowledge Entered Public Space

Across human history, access to information has shaped collective outcomes. Military success or failure, economic stability, cultural development, and political change all depended on how effectively knowledge could be obtained, recorded, and shared. Societies that recognised this invested effort in developing ways to circulate information, adapting their methods to the technical and social tools available to them.

In the ancient world, this led to a range of practices designed to make information public. News could be exchanged orally in communal spaces such as marketplaces and assemblies, or fixed in written form for repeated consultation. These methods were not static. Over time, they became more structured and more intentional, reflecting an increasing awareness of the value of regular, accessible information for both individuals and the wider community.

Rome represents a particularly developed stage in this process. While it is often assumed that the concept of a daily record of events belongs to the early modern period, Roman practice shows that this idea had already taken concrete form much earlier. By the late Republic, information of public relevance was being gathered, organised, and made available on a recurring basis.

The material included matters that would be recognisable as news even today: political decisions, legal actions, public events, and developments affecting the life of the community.

These practices demonstrate that Rome did not merely transmit information incidentally. It developed systems that allowed information to circulate regularly and visibly within the urban environment. Access to daily knowledge was not universal or equal, but the principle that certain facts should be made public had already been firmly established.

Before News Was Daily

As Rome expanded, so did the demand for structured information about events affecting the city and its wider territories. By the late Republic and into the Principate, the circulation of public knowledge had become a practical necessity rather than an occasional exercise.

Political life, military activity, provincial administration, and elite conduct generated a steady flow of events that required recording and communication. Within this environment, the decision traditionally attributed to Julius Caesar to formalise daily public reporting marked an important development. The Acta Diurna did not emerge in isolation but built upon earlier Roman practices of recording and organising information.

Annales: Recording the Year

One of the most established forms of written public record at Rome was the annales. These were yearly accounts that listed significant events in chronological order, organised by the calendar year (annus). While the recording of events over time was not unique to Rome, the Romans gave this practice a distinct form and terminology that would endure long after antiquity.

The annales focused on events deemed worthy of collective memory. They could include political developments, military actions, religious matters, prodigies, and occurrences affecting the city or the provinces. Their scope was not confined to Rome itself but extended to the wider world under Roman control. Over time, this mode of recording became closely associated with historical writing.

A number of Roman authors compiled works described as Annales, spanning several centuries. These ranged from early Republican writers to figures active well into late antiquity. The continuity of the genre reflects the lasting importance attached to annual record-keeping as a means of structuring historical knowledge.

The most influential surviving example is the Annals of Tacitus. Written after his earlier historical work, the Annals cover the period from the death of Augustus onward, presenting imperial history year by year. Although only parts of the work survive, its structure illustrates how the annalistic form could accommodate a wide range of material without altering its method.

The nature of the information included is revealing. Tacitus does not restrict himself to major political or military events. Personal conduct at the highest level of power appears alongside developments in distant provinces, treated with the same narrative discipline. In Book 14, for example, he records events surrounding Nero with a level of detail that brings private motives into public view:

“In the years of the consulship of Gaius Vipstanus and Gaius Fontius, Nero no longer postponed his long-planned crime… ‘All men wish to overthrow the mother’s power, but no man could have imagined that hatred of the son could lead to the murder of the mother.’”

(Tacitus, Annals)

Here, personal relationships within the imperial household are presented as matters of public consequence, recorded alongside official events. Elsewhere in the same book, Tacitus turns his attention to developments in the provinces, applying the same careful narration to matters far removed from the capital.

The annales therefore reveal a Roman conception of public information that was broad in scope. What mattered was not the nature of the event—whether intimate or administrative—but its perceived relevance to the life of the state. By organising such material year by year, Roman annalistic writing established a rhythm of expectation and recall that helped shape how information was preserved and understood.

This tradition of structured recording provided an important foundation for later developments. When daily information began to be displayed publicly at Rome, it did so against a background in which the regular documentation of events had long been accepted as essential to civic life.

Organising Time as Public Knowledge

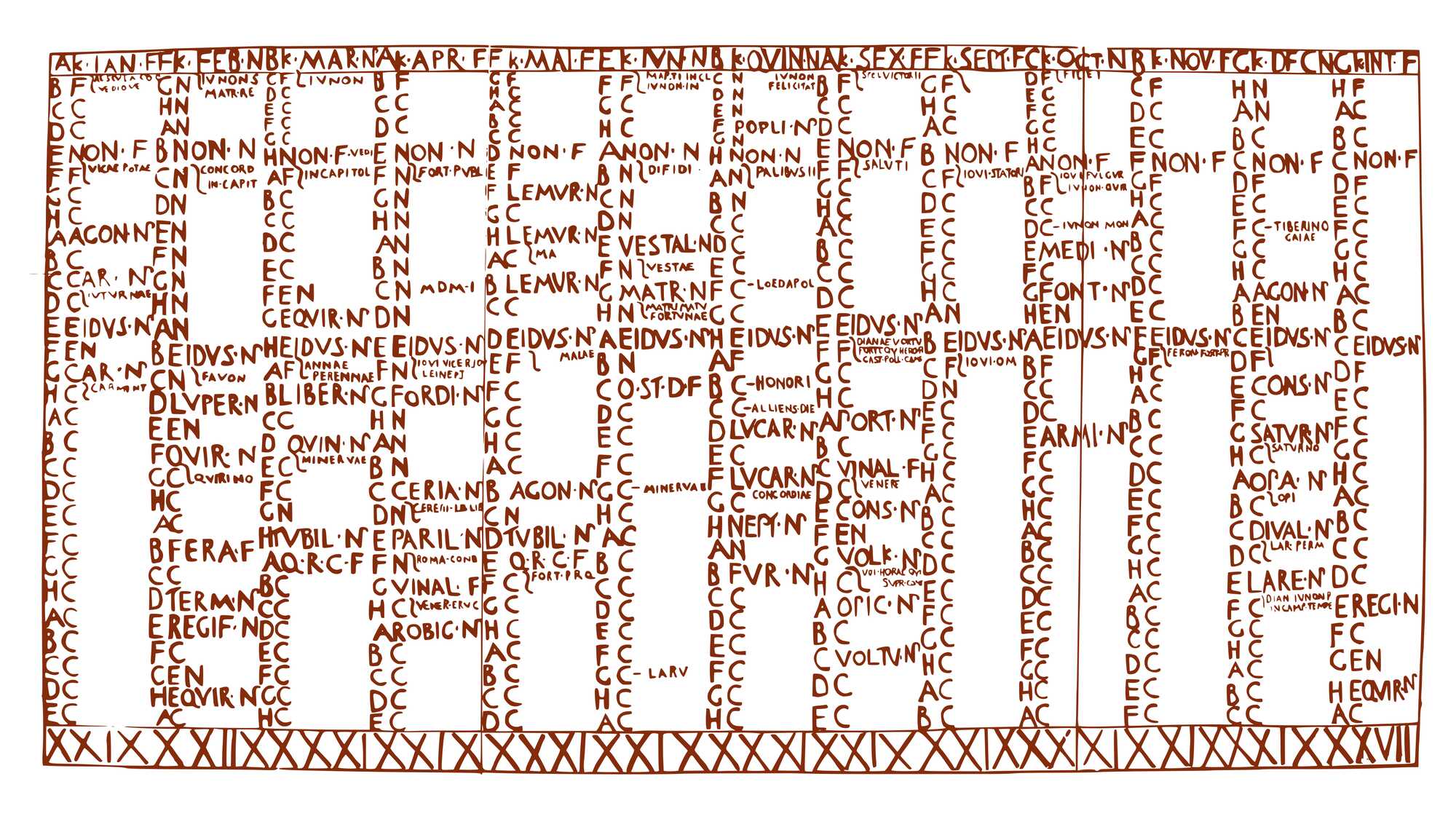

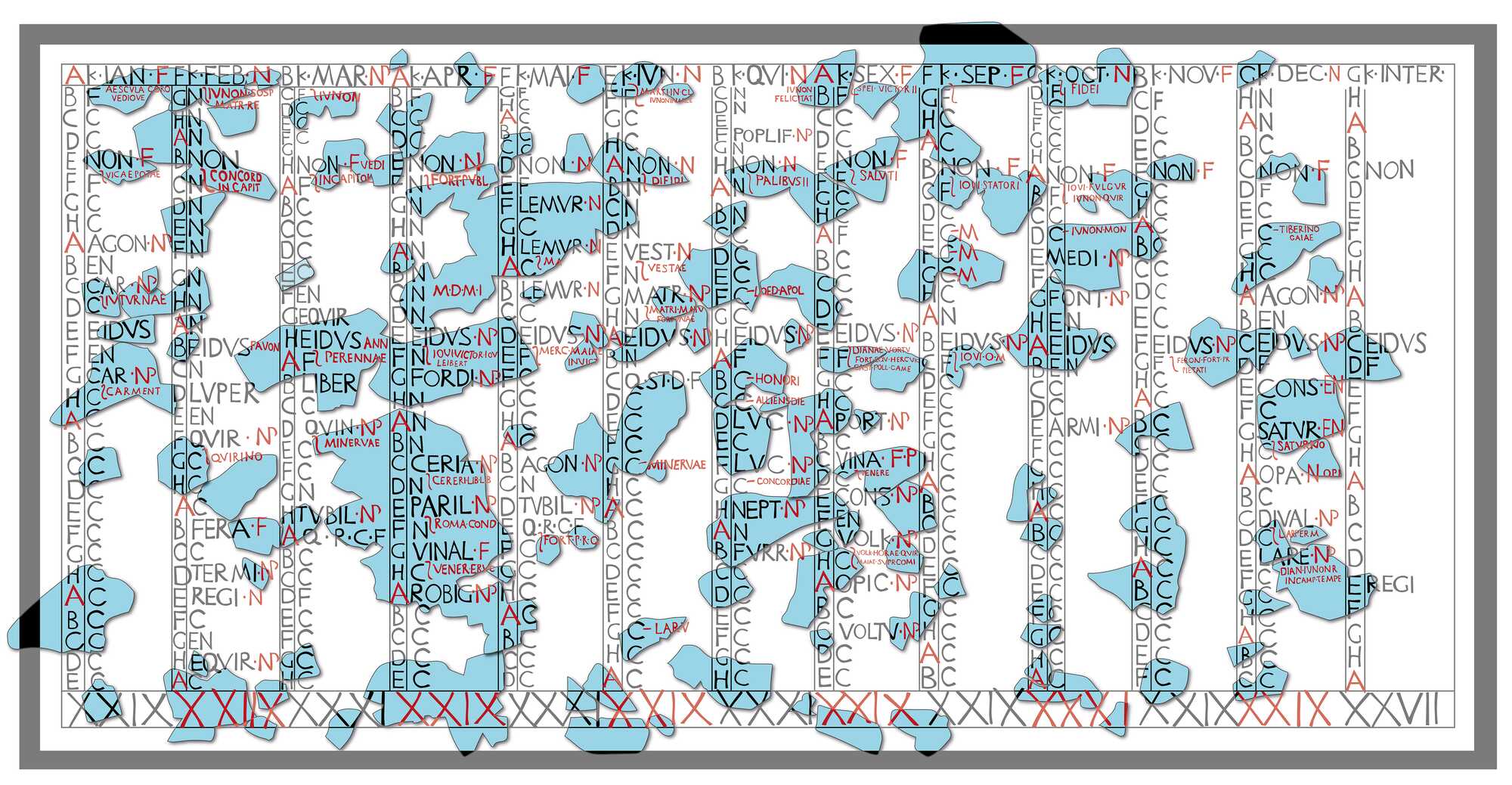

Alongside annals and oral reporting, Rome relied on another powerful tool for organizing public knowledge: the Fasti. These were official calendars, displayed publicly, that structured time itself by marking what could—and could not—be done on each day. More than a simple list of dates, the Fasti combined religious observance, civic administration, and historical memory in a single, visible format.

The term Fasti derives from fas, meaning what was permitted according to divine law. At its core, the calendar defined legitimacy: which days were suitable for legal business, assemblies, or public action, and which were barred by religious restriction. Compiling and maintaining this calendar was a priestly responsibility, and it was updated annually, month by month, to reflect both sacred and civic priorities. Lists of priests, magistrates, and officials were integrated into the structure of time itself.

The information contained in the Fasti extended well beyond religious observance. They recorded festivals, rituals, and auspicious days, but also noted political events, public works, and military achievements. Particularly prominent were the Fasti triumphales, which listed Rome’s victorious commanders and triumphs from the city’s earliest legendary rulers onward. In this way, the calendar became a monument of memory as much as a practical guide.

Some versions of the Fasti focused specifically on office-holding. The Fasti consulares, discovered on the Capitoline Hill in the sixteenth century and now known as the Fasti Capitolini, preserved the annual succession of consuls together with notable events that occurred during their terms. These lists offered a framework for dating the past and became an essential reference for Roman historical writing.

The calendar also divided days according to their function. Dies fasti permitted legal and administrative activity, while dies nefasti forbade it. Certain days were marked for assemblies (dies comitiales), while others were regarded as ill-omened. For a long time, this knowledge was restricted to elite circles. That changed in 304 BCE, when Gnaeus Flavius made the calendar public, allowing ordinary citizens to know when business could be conducted and when it could not. This act transformed access to civic time.

Over time, specialized forms developed. The Fasti magistrales focused on emperors and magistrates, recording days dedicated to their honors, ceremonies, and festivals. These were sometimes distinguished from more routine calendars and treated as official chronicles of imperial rule. At the same time, references to Fasti diurni point to calendars used for daily notation, blurring the boundary between timekeeping and news.

Fragments of the Fasti also preserve events of diplomatic significance. A notable example comes from Ostia, where a fragment records the visit of King Pharasmanes II of Iberia, his wife, and his son to Rome as guests of Antoninus Pius. Ancient historians describe the visit in detail, noting the honors granted to the king, including sacrifice on the Capitol and the erection of an equestrian statue. The appearance of this visit in the Fasti shows that such calendars did not merely track ritual cycles but also highlighted moments deemed important to Rome’s public life.

The influence of the Fasti extended into literature. Their structure inspired poetic treatments of the calendar, most famously in Ovid’s Fasti, which presents the Roman year through myths, rituals, and celestial movements. Here, the calendar becomes a narrative device, blending time, religion, and cultural identity.

By organizing religious observance, political authority, and historical memory within a shared temporal framework, the Fasti shaped how Romans experienced public life. They offered a daily reference point for what mattered, when action was permitted, and how the past should be remembered. In doing so, they helped lay the groundwork for later historical writing, which would adopt the same chronological logic while expanding it into continuous narrative.

Recording the Day Itself

The Acta Diurna, introduced under Julius Caesar during his first consulship in 59 BCE, represented Rome’s most far-reaching experiment in making information public on a daily basis. Unlike the Annals, which recorded only events judged historically significant, the Acta Diurna embraced a far wider range of material. Alongside matters of state, they included details that might otherwise have been dismissed as minor or incidental. What mattered was not hierarchy, but regularity and visibility.

None of the original notices survive, yet their scope can be reconstructed from later references. The Acta Diurna reported on leading political figures, imperial households in the Principate, official decrees, senatorial decisions, and imperial orders. They also recorded legal proceedings, including the progress and outcomes of trials, and allowed certain disputes to be made public. Beyond formal politics, the notices extended to the rhythms of urban life: construction and demolition projects, fires, natural disasters, and even circulating rumours.

This breadth distinguished the Acta from earlier forms of record-keeping. Their purpose was not simply to preserve memory, but to keep the population informed on an ongoing basis. The news was posted on tablets made of materials such as stone, metal, or wood, and displayed in prominent public spaces, most notably the Roman Forum. Although compiled in Rome, the notices circulated far beyond the city. They were read in the provinces and among the army, extending their reach across the empire.

Ancient authors provide glimpses of how these notices functioned. Suetonius remarks that Caesar was the first to order the daily publication of proceedings from both the Senate and the popular assemblies, indicating a deliberate policy of transparency. Cicero, writing privately, refers to consulting the Acta urbana of a specific date, suggesting that readers followed them closely and selectively.

Literary evidence reinforces this impression. In the Satyricon, Petronius presents a clerk reciting the city’s news: births and deaths, grain reserves, executions, financial transactions, and a fire breaking out in a tavern. The passage conveys the variety of material that could appear side by side, from state finances to everyday mishaps, all treated as part of the city’s public record.

Tacitus refers repeatedly to the Acta Diurna or Acta urbana in his Annals, using them as a point of comparison with historical writing. In one episode, he notes their silence on the presence of certain imperial figures at a funeral, implying that such notices were expected to contain detailed information about prominent individuals.

Elsewhere, he draws a clear distinction between genres: matters of lasting importance belonged in the Annals, while lesser events were left to the daily notices. He also observes that these reports were read attentively in the provinces and within the army, where they served as a means of tracking political developments at the centre.

Taken together, these references show that the Acta Diurna were widely accessible and socially inclusive. They circulated across geographic and social boundaries, reaching soldiers and civilians alike. By combining official decisions with the ordinary facts of daily life, they created a shared informational space in which the empire could see itself recorded, day by day. ("Methods and tools of information dissemination on a daily basis in the ancient world-from agoraa to Acta Diurna" by Ketevan Nizharadze, Doctor of Philology, Associate Professor, Georgian National University SEU)

Information as an Instrument of Rule

The Acta Diurna were not merely a collection of notices displayed in the city of Rome. They formed part of a broader system through which information was organised, controlled, and circulated within the Roman state. The publication of daily records must be understood within the wider administrative framework of the Republic and the early Empire, where political authority depended on the management of information as much as on military force or legal power.

Rome governed a territory that extended far beyond the city itself. Communication between the capital and the provinces was therefore essential to the maintenance of order. Official information flowed outward from Rome, reflecting a centralised model in which events, decisions, and public acts were recorded at the centre and then transmitted, in various forms, across the empire. The Acta Diurna operated within this structure, reinforcing Rome’s position as the primary source of authoritative information.

The survival of the empire depended in part on the efficient movement of news relating to political decisions, legal outcomes, military developments, and public affairs. The Acta Diurna contributed to this process by creating a recognised and regularised record of daily events that could be consulted, copied, and disseminated as required.

From the City to the Provinces

Although the Acta Diurna were displayed publicly in Rome, their reach extended well beyond the city. There is no evidence for large-scale mechanical reproduction or systematic state distribution. Instead, circulation relied on human networks. Copies were made by hand when necessary, and information was transmitted through letters, reports, and personal correspondence.

Elite communication played a significant role in this process. Senators, magistrates, and officials travelling or residing outside Rome sought access to the Acta through private channels. Cicero’s correspondence demonstrates an active interest in receiving specific daily reports, suggesting that the Acta were consulted selectively and valued for particular types of information. Access to the Acta outside Rome therefore depended on social position, personal connections, and the availability of literate intermediaries.

Despite these limitations, the Acta were known and read in the provinces and within the army. Tacitus notes that they were consulted in order to follow the actions of prominent individuals, indicating that their contents circulated far from their original place of display. This transmission was uneven, but it was sufficient to make the Acta part of a shared informational environment across the empire.

What Counted as News

The Acta Diurna recorded a wide range of material. Alongside formal announcements—such as senatorial decisions, legal judgments, and official decrees—they also included information of a more domestic or incidental nature. Births, deaths, executions, fires, public works, and unusual events were noted without clear distinction between what might later be classified as significant or trivial.

This breadth of content distinguished the Acta from annalistic writing, which focused on major political or military developments. The inclusion of minor occurrences suggests an intention to document the rhythm of daily life in the city as well as the actions of the state. The mixture of official and everyday material did not appear to trouble contemporary readers, who treated both as part of the public record.

The presence of such material also implies that the Acta were read aloud and discussed. Even those unable to read would have encountered their contents indirectly, through public recitation or private conversation. The Acta thus contributed to a shared awareness of events, even when access to the written text was limited.

When Silence in the Record Mattered

Ancient authors reveal that readers expected the Acta to provide detailed accounts of public and private affairs. Tacitus’ use of the Acta illustrates this expectation. In his discussion of the funeral of Germanicus, he remarks on what he did not find recorded. While other members of the imperial family were named, he notes the absence of any mention of Germanicus’ mother.

This silence is itself significant. Tacitus’ search implies that the Acta were assumed to contain such information and that omissions were meaningful. The Acta were therefore not only a source of information but also a reference point against which absence could be measured. Their authority rested not on completeness alone, but on the expectation that they would normally record matters of public visibility.

Being Seen – or Not – by the Public

Ancient writers were aware that the Acta were not neutral records. Livy refers to early doubts about official documentation, and Tacitus alludes to selective reporting and manipulation. Despite this awareness, the Acta continued to be consulted and cited.

Their authority did not depend on unquestioned accuracy but on their status as an official source. Readers approached them with a degree of caution, yet still regarded them as an essential repository of public information. The Acta occupied a space between record and representation, where trust was negotiated rather than assumed.

Why the Acta Did Not Last

There is no evidence that the Acta Diurna survived beyond the administrative and social conditions that sustained them. They depended on urban literacy, bureaucratic continuity, and the concentration of authority in Rome. As these conditions weakened, so too did the mechanisms that supported daily public records.

No proof exists for their continuation into late antiquity in a recognisable form. Their disappearance appears to coincide with broader changes in governance, communication, and record-keeping, rather than with any formal abolition. ("Ancient Rome's Daily Gazette' by C.A Giffard)

The Acta Diurna did not survive because they were innovative, nor because they were comprehensive. They endured for as long as the administrative, social, and urban conditions that sustained them remained intact. When those conditions changed, the daily record faded—not abruptly, but as part of a broader transformation in how information was produced, displayed, and controlled.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: