Why did the Roman Empire Fall? An Analysis by Experts

The Roman Empire, once the epitome of strength and stability, began a slow and intricate decline long before its ultimate collapse. This process was influenced by an interplay of internal weaknesses and external pressures, spanning centuries.

The fall of the Roman Empire is one of the most pivotal events in Western history, marking the transition from the ancient to the medieval world. While the Empire’s decline was gradual and occurred over centuries, historians typically cite 476 AD as its endpoint, when the last Roman emperor of the West, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed.

The reasons behind the fall are complex and multifaceted, involving a blend of internal weaknesses and external pressures that accumulated over time. The decline of the Roman Empire is a complex topic with many layers. At its peak, it extended from the damp hills of northern England to the dry deserts of Saudi Arabia.

The specific moment when the Empire began to crumble is debated among historians. Some point to the sacking of Rome by the Visigoths in 410 AD as a significant marker of its end, while others believe the Empire continued until the Middle Ages.

The Empire was formally divided in 395 AD into the Western Roman Empire, with Rome as its capital, and the Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantine Empire, with Constantinople (now Istanbul) as its capital. This division marks a significant shift in how the Empire was governed.

"We tend to think of the Byzantines as this separate people and state from the Romans, but they called themselves "Romanoi" and saw themselves as citizens of a Roman government"

Kristina Sessa, associate professor of history at The Ohio State University

The decline of the Western Roman Empire was characterized by a gradual loss of centralized control, influenced by various factors including invasions by non-Roman tribes and betrayals within the Roman establishment itself. Pinpointing an exact moment when Rome lost control over specific territories is challenging. Unlike the clear-cut decolonization events of the 20th century, the disintegration of Roman control was not typically marked by formal documents or declarations of independence.

Between AD 460 and AD 480, for example, the Visigoths successfully captured significant portions of what is now France. The decline was not a sudden collapse but a slow and indistinct process where local autonomous leaders gradually took over the governance of regions previously under the control of a Roman emperor.

So Why did Rome Fall?

A Crumbling Foundation: The Loss of Civic Virtue

Edward Gibbon's “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” (with notes by H. H. Milman), provides a detailed exploration of the factors leading to the Roman Empire's decline, blending historical narrative with his interpretations:

At the heart of Rome’s decline lay a gradual erosion of civic virtue and moral fiber among its citizens. The republican values of duty and self-sacrifice, which had once propelled Rome to greatness, gave way to personal ambition and complacency. The citizenry, increasingly preoccupied with luxury and spectacle, grew detached from the responsibilities of governance and military service.

This shift was mirrored in the Roman elite, whose pursuit of personal wealth and influence eroded the unity of the state. Public offices, once held as a mark of honor and service, became tools for personal enrichment, and corruption spread throughout the administrative machinery. The resulting inefficiency and dishonesty weakened Rome’s ability to respond effectively to crises.

Rome’s cultural landscape shifted dramatically in its later years. Once a society built on discipline and civic responsibility, it became increasingly characterized by luxury and self-indulgence among the elite. Public officials, motivated by personal gain, neglected their duties, while the general populace became disengaged from the affairs of state.

Gibbon attributes part of this decline to the influence of Christianity, arguing that its emphasis on spiritual life led to a diminished focus on worldly matters. This perspective, while reflective of his own biases, highlights the significant cultural transformations that marked the empire’s later years.

Economic Strain and Its Consequences

The empire’s vast size brought not only glory but also immense economic challenges. Maintaining the Roman military, infrastructure, and bureaucracy required substantial resources, which placed a heavy burden on provincial economies and citizens. Excessive taxation stifled productivity, while the uneven distribution of wealth bred discontent and social unrest.

Over time, economic exploitation of the provinces drained them of vitality, reducing their ability to sustain Rome’s needs. Agricultural decline, compounded by mismanagement and over-reliance on slave labor, further exacerbated the financial strain. As the empire struggled to balance its expenses, the silver content of Roman coins was gradually reduced, leading to rampant inflation and a loss of confidence in currency.

Economic challenges compounded Rome's decline. The empire’s vast infrastructure required immense resources to maintain, leading to heavy taxation that stifled provincial economies. Inflation and debasement of currency further eroded economic stability, while corruption within the administration exacerbated inefficiencies.

Agricultural production declined, particularly in the western provinces, where repeated invasions devastated the land. The reliance on slave labor proved unsustainable, limiting innovation and adaptability in the face of changing economic conditions.

Military Decline and Vulnerability

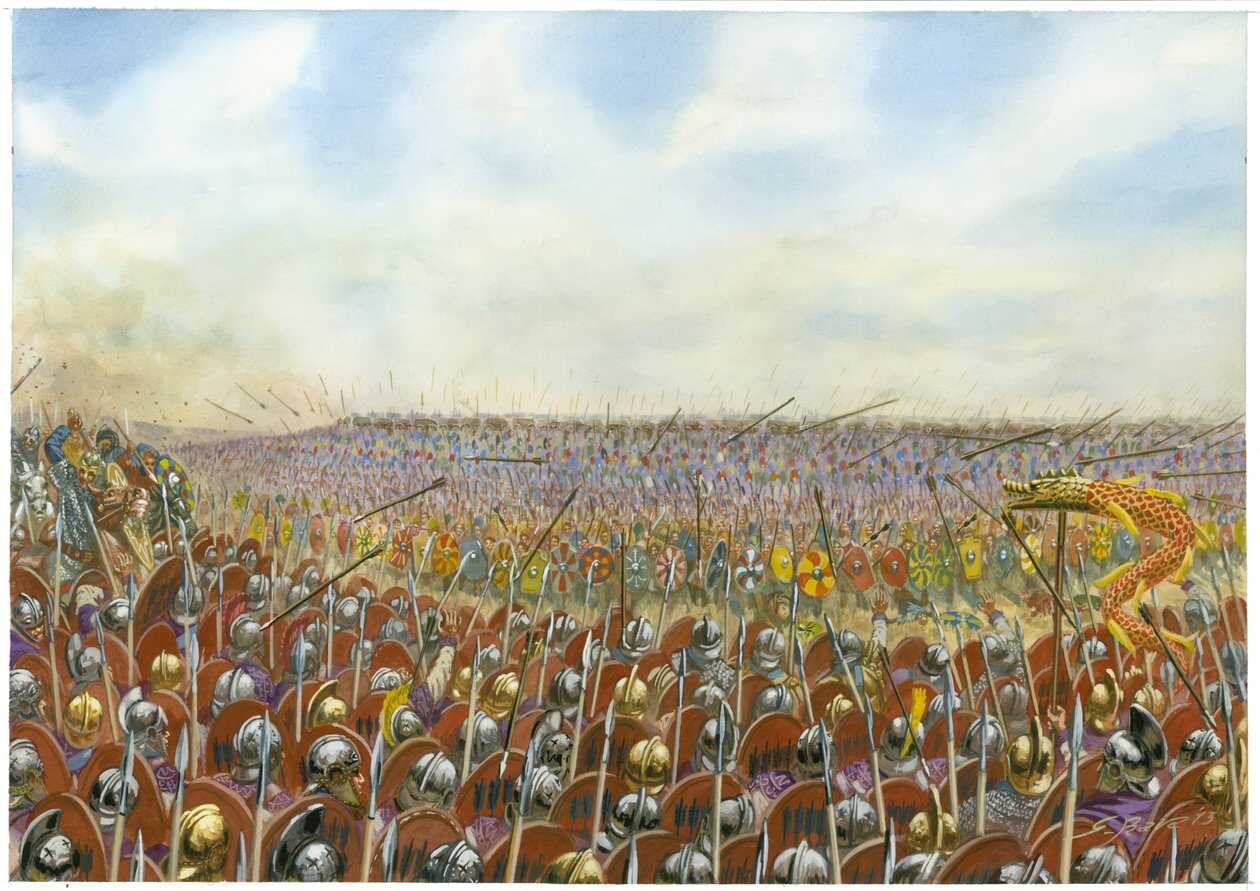

Rome’s military power, the cornerstone of its empire, began to falter due to internal decay and external pressures. The once-disciplined legions were increasingly staffed by conscripts and mercenaries, many of whom lacked loyalty to the empire. Barbarian auxiliaries, while useful in the short term, often undermined cohesion within the army and posed a risk of rebellion.

The empire's military, once its greatest strength, continued to deteriorate. The reliance on barbarian auxiliaries introduced instability, as these groups often prioritized their own interests over those of Rome.

The Battle of Adrianople in 378 CE, where the Roman army suffered a devastating loss to the Visigoths, underscored the empire’s declining ability to defend its frontiers. This loss not only weakened Rome militarily but also emboldened other barbarian groups to challenge its authority.

Barbarian Invasions: The Pressure from Without

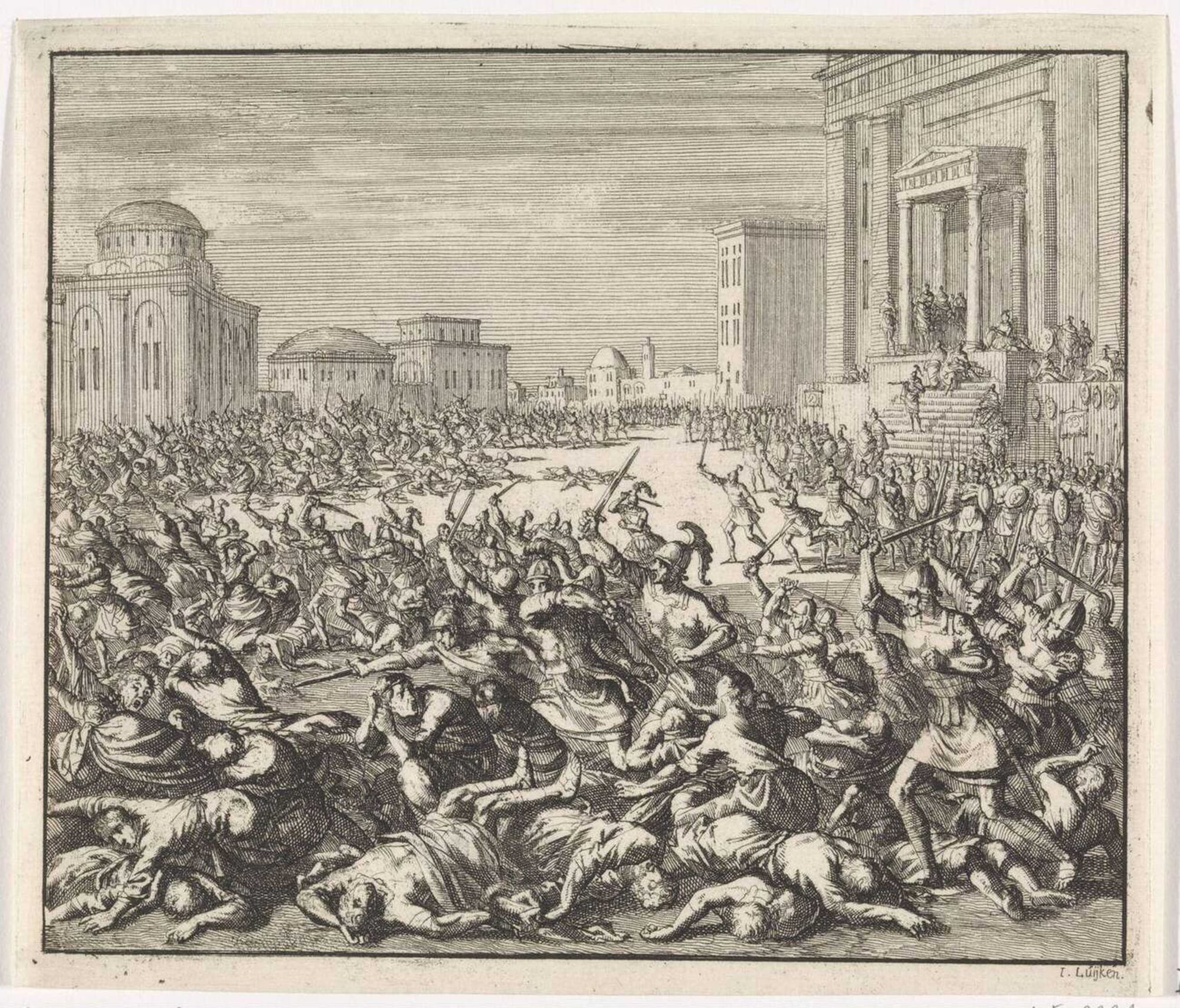

As Rome’s internal structure weakened, external pressures from barbarian groups intensified. The migration and invasion of peoples such as the Goths, Vandals, and Huns destabilized the western provinces. These groups, driven by a combination of environmental changes, population pressures, and the allure of Roman wealth, sought both plunder and settlement within the empire’s borders.

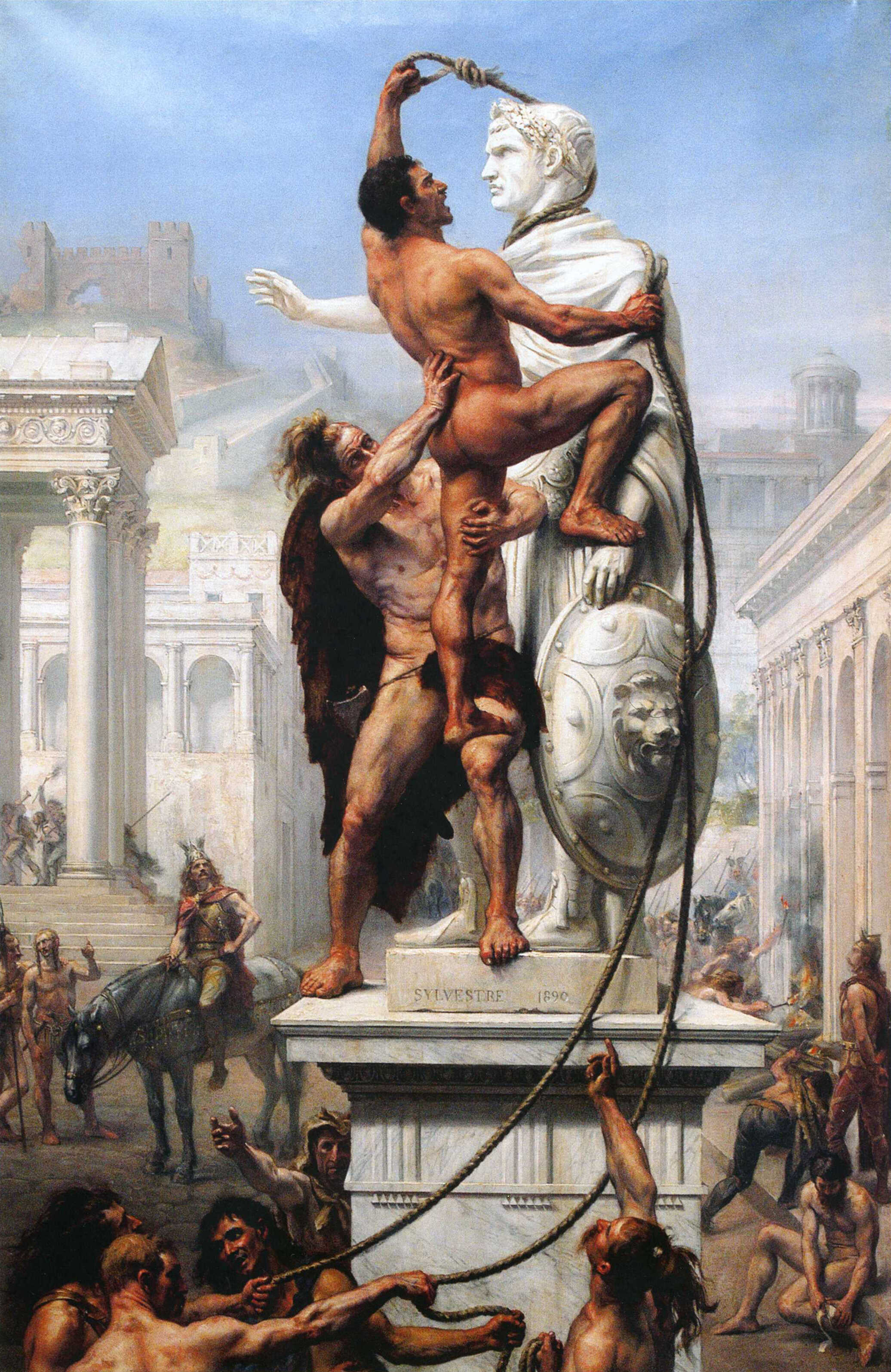

The sack of Rome in 410 CE by the Visigoths and the Vandal conquest of North Africa dealt severe blows to the empire’s prestige and resources. The inability to repel these invaders signaled the empire’s waning power and the erosion of its influence in the western territories.

The Religious Shift and Its Implications

One of the most significant shifts during Rome's decline was the rise of Christianity. Initially a persecuted sect, Christianity gained traction through its promise of salvation and its appeal to the disenfranchised. As emperors like Constantine began to favor the religion, it moved from the fringes of society to the center of imperial policy.

The Edict of Milan in 313 CE, which granted religious toleration, marked a turning point. Over time, Christianity’s dominance reshaped the moral and cultural fabric of the empire. Traditional Roman virtues of civic duty and martial valor gave way to a focus on spiritual salvation, often diverting attention from the practicalities of governance and defense.

Christianity also reshaped the Roman political landscape, with church leaders gaining influence alongside secular authorities. This dual power structure occasionally led to conflicts of interest, further complicating governance during critical periods of instability.

Before its acceptance, Christianity faced intense persecution under several emperors. Efforts to suppress the faith through violence and legal measures failed to quell its growth. As Christianity became intertwined with imperial authority, it created both unity and discord.

The elevation of Christianity as the state religion under Theodosius I, through policies like the prohibition of pagan practices, led to cultural clashes and further divided an already fragmented empire. Religious dissent and theological debates, such as those surrounding Arianism, consumed imperial resources and attention at critical moments.

The Splintering of Power and the Fall of the West

The division of the Roman Empire into eastern and western halves under Emperor Diocletian created administrative challenges that persisted for centuries. While the eastern half, centered on Constantinople, retained much of its stability and resources, the western half became increasingly fragmented.

In 476 CE, the deposition of Romulus Augustulus by the Germanic chieftain Odoacer is traditionally marked as the end of the Western Roman Empire. This event symbolized the culmination of centuries of decline, leaving the eastern empire, known as the Byzantine Empire, to carry on Rome’s legacy for nearly a thousand more years.

The lack of cohesion between the two halves, combined with their divergent fortunes, hastened the decline of the western provinces. This division created a scenario in which the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE became inevitable, even as the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire continued to thrive.

A Story of Resilience and Transformation

In “The Fall of the Roman Empire: Film and History”, edited by Martin M. Winkler, we see a similar approach. We read that far from the dramatic implosion often imagined, the Roman Empire’s decline was a gradual process spanning centuries. By the time Romulus Augustulus, the last Western emperor, as already mentioned was deposed in 476 CE, the empire had already morphed into a patchwork of smaller kingdoms.

These new polities were not merely Rome’s destroyers but also its heirs, preserving elements of Roman governance, law, and culture.

Genserich's Invasion of Rome, a painting by Karl Bryullov. Public domain

Modern historians highlight that the “fall” was not experienced uniformly. In the Eastern Mediterranean as aforementioned, the Byzantine Empire flourished for nearly a millennium after the Western Empire’s fall, safeguarding Roman traditions and fostering their adaptation to new cultural and religious contexts.

On the other hand, Arther Ferrill in his book, “The Fall of the Roman Empire: The Military Explanation”, claims that the main reason for Rome's collapse was not its internal fragility, as some historians have suggested, but rather the decline of its military forces.

Ferrill says that Rome built one of the most powerful empires in the Western world, with legions defending an expanse stretching over three thousand miles, from Britain to Egypt, and safeguarding borders nearly six thousand miles long. The phrase “the grandeur that was Rome,” famously coined by Poe, continues to captivate poets, historians, and the general public alike.

Emperors and empresses, military might, administrative brilliance, and grand pageantry created an enduring image of eternal strength.

The Colosseum in Rome. Credits: The_Double_A from pixabay, by Canva

The Rome of Augustus and Nero, of Christ and St. Paul, was seen as encompassing the entire civilized world, excluding only the untamed barbarians on the outskirts and the decadent Parthian Empire.

The physical legacy of this majestic civilization endures in ruins such as Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, the aqueducts of France and Spain, the Colosseum in Rome, and the remains of Roman North Africa. Across the Mediterranean, travelers encounter reminders of Rome's former greatness, where the mere will of an emperor once inspired awe.

A vivid anecdote illustrates Rome's power: Favorinus, a rhetorician and friend of Plutarch, deferred to Emperor Hadrian in a linguistic debate, justifying his concession with the words, “Who am I to argue with the commander of thirty legions?”

Rome’s achievements extended beyond its imposing architecture and military dominance. The Pax Romana brought peace and prosperity, accompanied by a sophisticated legal and administrative system that united diverse peoples and cultures. Virgil captured this spirit in his poetry, lauding Rome’s rule of peace and justice. While the empire exploited its subjects, it retained their loyalty and even admiration for centuries.

The intellectual, aesthetic, and literary contributions of Rome are unmatched, rivaled only by ancient Greece. Virgil’s Aeneid, inspired by Homer, solidified his place among the greatest epic poets, alongside Homer and Milton. Tacitus, though not Thucydides, remains a formidable historian of antiquity. However, Rome’s practical triumphs may eclipse even its intellectual ones.

The empire set a standard of living unparalleled for centuries, with abundant fresh water delivered by aqueducts, heated public baths, and advanced sewer systems. These facilities, spread from Hadrian’s Wall to the Greek East, offered Romans hygiene and comfort unheard of until the 19th century.

This sense of achievement fostered belief in Roma Aeterna, the eternal city. Yet, despite its grandeur, Rome proved mortal, and its fall has haunted the Western imagination ever since. As one historian remarked, “The best-known fact about the Roman Empire is that it declined and fell.” Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” remains the quintessential work on the subject.

Over time, countless explanations for the fall have emerged, with one study listing over 200 theories. While the multiplicity of interpretations may seem overwhelming, exploring the fall of Rome offers valuable insights into one of history's most enduring enigmas.

The fall of the Roman Empire is not just the story of what was lost but also what endured. Roman law, engineering, and urban planning became the foundation of medieval Europe and influenced societies as distant as the Islamic Caliphates. Latin, the language of the empire, remained a lingua franca of education and religion for centuries.

Even the image of Rome as a “fallen” empire carries symbolic power. Its story has been retold through countless lenses, reflecting the concerns of successive generations. For Renaissance humanists, Rome was a golden age lost. For Enlightenment thinkers like Gibbon, it was a cautionary tale of decadence and mismanagement. Today, the empire’s decline is studied not as an end but as a transformation—an evolution that gave rise to new worlds.

Why Two Empires?

In 324 CE, Constantine emerged victorious against Licinius, the eastern emperor, effectively uniting the Roman Empire under his rule. He established a new capital in the eastern half of the empire, at Byzantium, which he rechristened as New Rome; the city later became known as Constantinople, in honor of its founder.

The strategic location of Constantinople on a defensible peninsula and near the empire's frontiers enabled quicker military responses to external threats. Additionally, some historians suggest that Constantine chose this site for his new capital to foster the growth of Christianity away from the perceived corruption of Rome, providing a nurturing environment for the burgeoning religion.

The increasing involvement of church leaders in political matters further complicated the governance of Rome. Edward Gibbon famously supported the theory that Christianity contributed to the decline of Roman civic and moral virtues, a stance that has since faced significant scrutiny.

Today, most scholars believe that while Christianity might have influenced some aspects of Roman culture, the major causes of the empire's decline were more related to military, economic, and administrative challenges rather than religious transformation.

The Western Roman Empire, where Latin was the primary language and Roman Catholicism the predominant faith, faced a steady decline, ultimately leading to its downfall. In contrast, the Eastern Roman Empire, which spoke Greek and practiced Eastern Orthodox Christianity, continued to flourish long after the west fell. This eastern continuation, known as the Byzantine Empire, thrived for centuries thereafter.

Consequently, the term "fall of Rome" specifically refers to the collapse of the western half of the Empire.

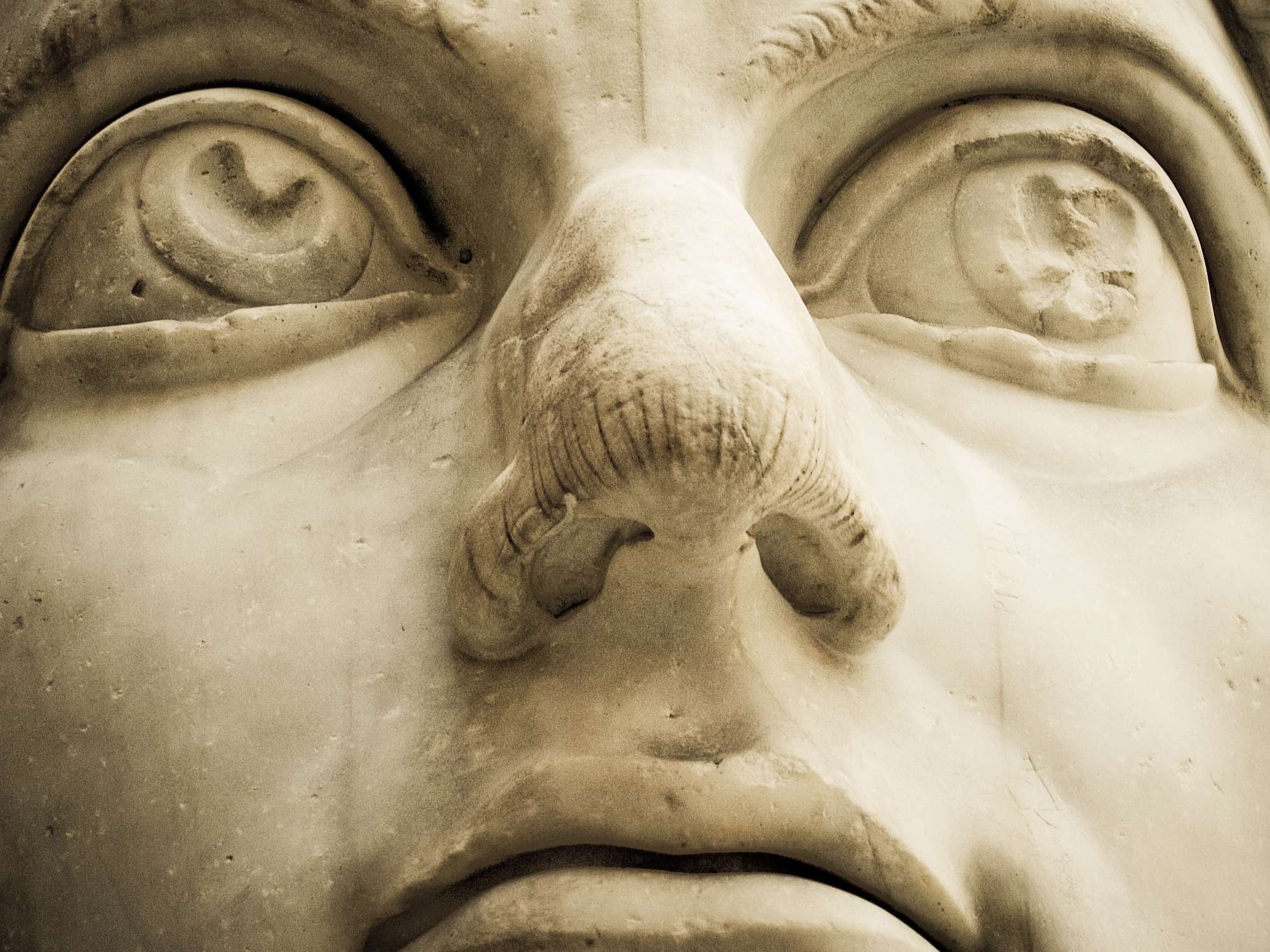

The colossal head of Roman Emperor Constantine, in the Capitol, Rome. Credits: javarman3 from Getty Images, by Canva

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: