What Was the Pax Romana? Was Rome ever a Peaceful Empire?

The concept of Pax Romana—the Roman Peace—represents a significant period of stability and order across the Roman Empire, inaugurated during the reign of Augustus.

The term Pax Romana was closely associated with Augustus, who declared the "Augustan Peace" as a cornerstone of his rule. Despite his rhetoric of peace, Augustus pursued aggressive territorial expansion, particularly in Spain and Germany. This duality highlights the tension between the ideology of peace and the reality of Roman military campaigns.

The Expansion of the Roman Empire: Geography, Motives, and Challenges

By 31 BCE, the Roman Empire encompassed most of the Mediterranean basin, primarily dominating coastal regions. While areas like Spain and Gaul constituted substantial landmasses, territories such as Italy, Dalmatia, Greece, Macedonia, Asia Minor, Cyrenaica, and parts of North Africa remained concentrated along the coasts.

The empire, centered on the Mediterranean, relied heavily on maritime communication, as Roman conquests naturally followed the logic of expansion rather than any premeditated imperial design.

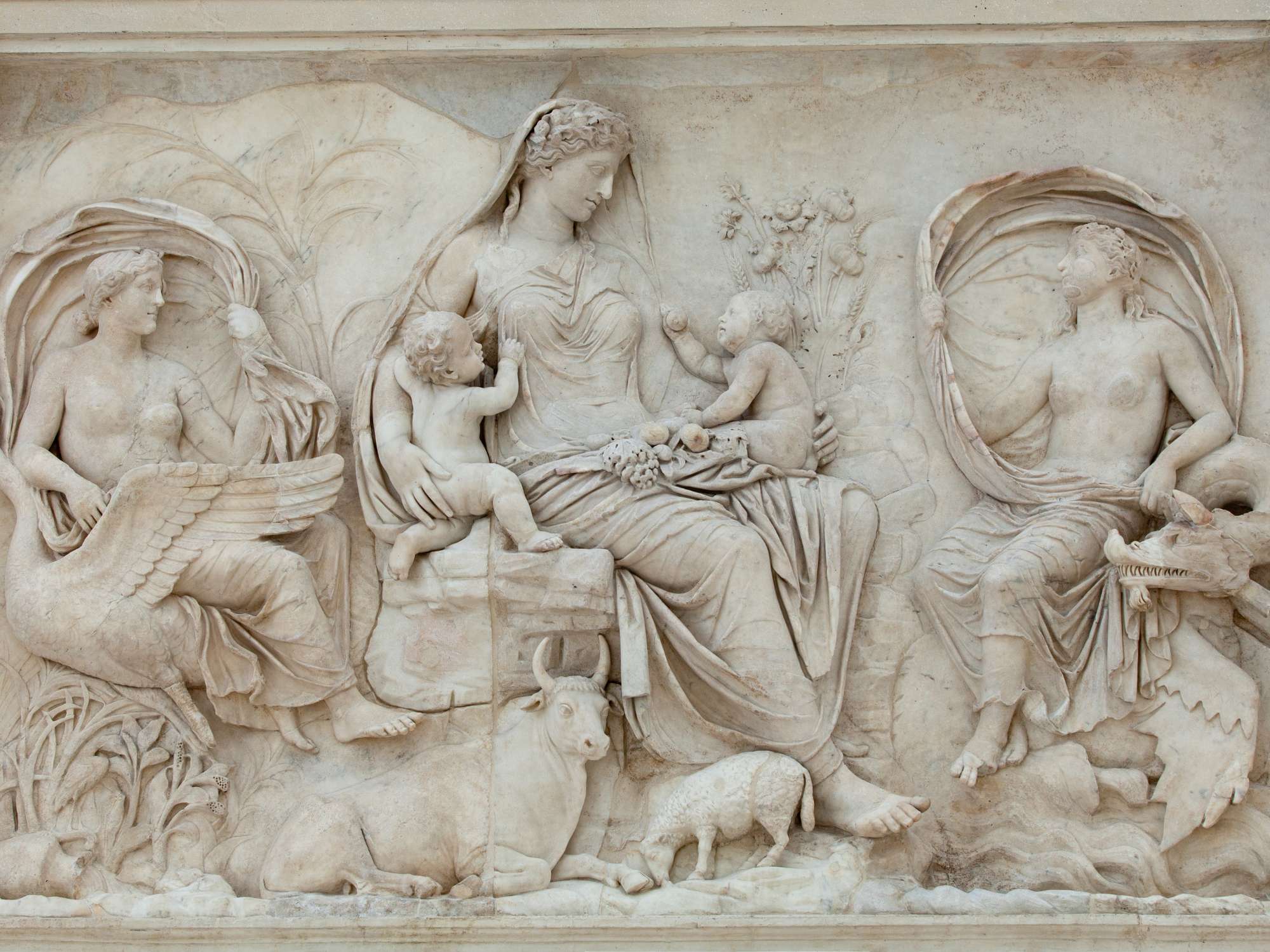

A detail from the Ara Pacis altar. Credits: wjarek from Getty Images, by Canva

By the late 2nd century CE, Roman territorial control had nearly doubled. The empire now covered the entire Mediterranean littoral and extended significantly inland. Conquests in Spain and Gaul eradicated independent regions, Britain was occupied up to the Scottish border, and Northern Africa stretched to the Sahara. Rome's dominance extended up to the Danube, including parts of Dacia, and Egypt reached beyond the First Cataract.

The only exception to Rome’s inland expansion was along the Rhine, where a lack of Roman bridgeheads persisted between Koblenz and Nijmegen (cities in Europe, significant for their historical importance in the Roman Empire as key locations along the Rhine River, which marked the boundary of Roman territory in certain periods). While these conquests were extensive, they were not driven purely by imperial ambition or economic exploitation. Most expansion aimed to secure natural frontiers and protect vital Roman provinces.

For instance, conquests in the Danube region shielded Cisalpine Gaul and Dalmatia, while the reduction of Galatia and Cappadocia safeguarded Cilicia and Bithynia. Similarly, securing Mauretania, Numidia, and Tripolitania ensured the safety of African coastal areas. Other expansions, like the occupation of Arabia, secured key trade routes, and Britain’s annexation curtailed Frisian piracy.

Despite this calculated expansion, certain anomalies, such as the unbuffered frontier along the Rhine, left Roman territories vulnerable to barbarian incursions. The shift in Roman opponents—from centralized states like Carthage and Hellenistic kingdoms to scattered barbarian tribes—marked a new phase of military challenges.

Unlike the structured battles of earlier campaigns, Roman armies now faced relentless guerrilla warfare, where marshlands and woodlands offered perfect terrain for ambushes. These barbarian tribes, lacking diplomatic protocol and hardened by their rugged environments, proved resilient and defiant. Conquests in these regions were prolonged, logistically demanding, and often punctuated by uprisings, as these tribes resisted Roman authority and resented the loss of liberty and fiscal exploitation that followed Roman occupation.

By the end of the 1st century CE, Roman expansion had largely stagnated. Trajan’s Parthian campaign in the early 2nd century was an isolated and ultimately unsuccessful endeavor. Nevertheless, the empire had established natural and artificial defenses that kept the barbarians at bay, granting the Roman world a relative peace lasting for about half a century, particularly from the reign of Hadrian to Marcus Aurelius.

This period, marked by strategic conquests and calculated defenses, underscores Rome’s transition from aggressive expansion to consolidation. It highlights the empire’s ability to adapt to changing challenges, from centralized states to unyielding tribal adversaries, ensuring its stability and longevity despite the arduous nature of maintaining its vast territories. (Pax Romana, by Paul Petit)

The Ideology of Rome's "Peaceful" Empire

Ali Parchami, a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Defense and Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, has presented in his book “Hegemonic Peace and Empire” a different perspective of what Pax Romana was.

He begins by saying that the term is used by modern historians to describe the state of the Roman Empire during the two and a half centuries following the fall of the Republic. Often portrayed as a "golden age," this period is celebrated for its socio-political stability, economic prosperity, cultural achievements, and administrative efficiency.

Edward Gibbon (an 18th century English rationalist historian and scholar best known as the author of “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” (1776–88)) famously described it as an era when:

“the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous,”

particularly highlighting the Antonine age. According to Gibbon, only minor conflicts occurred at the empire's frontiers while the rest of the realm enjoyed what he called "universal peace," with the Roman name revered even in distant lands.

This narrative has been widely accepted, presenting the Pax Romana as a peak of human achievement and a cornerstone of Western civilization. Today, it is often perceived as an age of tranquility, where diverse peoples across the Mediterranean were unified under a single dominion.

However, little attention is given to its actual characteristics, including the language and ideology underpinning this so-called peace. Three key questions emerge:

A detail from the side of the Ara Pacis wall. Credits: tupungato from Getty Images, by Canva

- Did it signify peace across the empire or only along troubled frontiers?

- Was it a real and quantifiable peace, or merely Roman propaganda?

- What was the Roman conceptualization of peace, and how was it intertwined with notions of military dominance and imperial hegemony?

The Nature and Ideology of Roman Pax

From its inception, pax was deeply rooted in military and religious traditions. It carried strong hegemonic and militaristic overtones, often intertwined with terms like “pacification,” “victory,” and “conquest.” Under the empire, particularly during the reign of Augustus, pax became a cornerstone of imperial propaganda.

Augustus’ ideology promoted the twin concepts of Pax Augusta and Pax Romana, which symbolized the end of civil wars and suggested peace across the provinces and security at the empire’s frontiers. Yet, Roman peace was far from the modern concept of peace.

It was achieved through war, conquest, and maintained by Roman military dominance and what was framed as "benevolent rule."

A detail from the Ara Pacis wall. Credits: Flory from Getty Images Signature, by Canva

Romans believed in their own cultural superiority and viewed their empire as having a providential destiny and a civilizing mission. This belief was encapsulated in the concept of imperium sine fine—an empire without boundaries. Thus, the Pax Romana was less about harmony and more about enforcing Roman order across its dominion.

In a narrow sense, Pax Romana represented hegemonic peace within the framework of Roman imperialism. However, its broader conceptualization encompassed the essence of everything imperial Rome stood for—its social, political, cultural, and military ideology.

Domestically, pax was closely linked to terms like concordia (harmony and unity) and salus (security), which underscored the importance of order and stability within the Roman state. These ideals became tools of political propaganda, first utilized during the late Republic by figures like Sulla and later Augustus to signal the restoration of order after periods of upheaval.

Personification and Symbolism of Pax

The goddess Pax served as a powerful symbol of Roman peace. On coins and other representations, she was often depicted as a young woman holding a cornucopia and olive branch or a caduceus. Unlike the Greek goddess Eirene, who represented mutual peace between equals, Pax symbolized Rome’s might.

Trajanic coins, for example, portrayed her with a foot on the neck of a defeated enemy, reinforcing the militaristic and supremacist nature of Roman peace.

A coin from Trajan’s reign, depicting Goddess Pax draped, standing to left, holding branch in right hand and cornucopiae in left, right foot treading down a fallen Dacian. Credits: CoinArchives, Mesamong from Getty Images, Composition by Roman Empire Times

Religion played a crucial role in shaping the Roman understanding of pax. The concept of pax deorum—the harmony between mortals and the gods—was central to Roman religious practices. Maintaining this harmony was believed to ensure the success and prosperity of the state, which in turn reinforced the idea that Roman pax was both divinely sanctioned and a reflection of the empire’s supremacy.

In essence, the Pax Romana was not merely an absence of war but a carefully curated ideology that justified and perpetuated Roman imperialism. It symbolized the Roman worldview of order, domination, and civilization, achieved through military conquest and sustained by a self-perception of unparalleled cultural and political superiority.

The Duality of War and Peace

The concept of Pax Romana encapsulated a complex interplay of ideas revolving around Roman military power abroad and domestic security and prosperity, all underpinned by state authority and divine favor. However, fully understanding pax requires exploring the terminology, symbolism, and militaristic ethos that defined Roman peace, as well as the Romans’ attitudes toward warfare.

As aforementioned, a range of Roman virtues and ideals—concordia (harmony), gloria (glory), fides (loyalty), imperium (command), laus (praise), pietas (piety), salus (security), virtus (courage), and victoria (victory)—highlighted the inseparability of war and peace in Roman thought. We have to note that these terms reflected a society deeply entrenched in militarism, where political, institutional, and cultural frameworks revolved around war.

As William Harris (a prominent historian and scholar of the Roman world, particularly known for his influential work on Roman imperialism, militarism, and the socio-economic aspects of the ancient Mediterranean. One of his most significant contributions is the book "War and Imperialism in Republican Rome, 327–70 BC," where he explores how militarism and imperial expansion shaped Roman society during the Republic) observed, success in warfare was the pinnacle of achievement for Roman patricians during the mid-Republic, shaping the ambitions of the elite.

Polybius noted that no Roman could hold political office without completing at least ten military campaigns, and Sallust attributed Rome’s rapid expansion to its insatiable desire for glory.

A detail from the side of the Ara Pacis, a procession of members of the Senate. Credits: Francesco Cantone from Getty Images Signature, by Canva

This martial culture extended beyond the nobility, permeating all levels of society, as average citizens readily embraced the brutality of war, drawn by the economic and social opportunities it offered. The Romans justified their wars through the doctrine of iusta causa (just war), which required divine sanction through the ceremony of the fetiales.

In theory, wars were fought in self-defense or to protect allies, but in practice, the concept of “protecting allies” served as a pretext for unending expansion. Any independent power was perceived as a potential threat to Rome’s security, necessitating conquest. This relentless pursuit of dominance left little room for the desire for peace that was evident in the Hellenistic world.

Instead, Roman literature and culture from the mid-Republic onward celebrated militarism as intrinsic to the Roman state. From its inception, Rome’s institutions, religion, and moral values were suffused with a militaristic ethos. Livy, the historian, captured this duality when he attributed Rome’s success to the combined legacies of Romulus, the warlike founder, and Numa, the peaceful king.

Livy emphasized that war and peace were not opposites but complementary aspects of Roman ideology, with war serving as the foundation for peace. This duality was also reflected in symbolic representations, such as the Temple of Janus. The temple’s gates remained open during times of war and were ceremoniously closed only in times of peace. During the Republic, the gates were rarely closed, underscoring the dominance of victoria over pax in state symbolism.

However, the ideology of pax was not undermined by this emphasis on war; rather, it was seen as a condition achieved through military success. In the Empire, under the auspices of Pax Augusta, the emphasis shifted to peace, but the connection between war and peace remained clear to Roman audiences.

As Cicero noted, war was often a necessity to secure a peace free from injustice. Claudian, writing centuries later, echoed this sentiment, describing Rome as enjoying the blessings of peace while reaping the advantages of war. The two-faced god Janus symbolized this duality, embodying the intertwined nature of war and peace in Roman ideology. Thus, while victoria dominated the Republic, pax emerged as the defining ideal of the Empire, though always grounded in the reality of Roman military power.

Ideology, Policy, and the Lasting Peace of the Roman Empire

The Beginning of Pax Romana: A New Era of Stability

In order to properly understand the concpet, it is necessary to take a deep dive into the term Pax Romana, or Roman Peace, that evokes images of an empire united under a banner of stability, prosperity, and order. This era, inaugurated during the reign of Augustus, marked a transformative period in Roman history, one in which the ideals of peace and governance were intertwined with the realities of military strength and imperial ambition.

Augustus positioned himself as the architect of this peace, proclaiming the Augustan Peace as a defining achievement of his rule. However, this peace was far from passive; it was built upon a foundation of strategic conquests and ideological assertions of Roman superiority.

While Augustus championed the narrative of a Rome dedicated to peace, his policies often contradicted this ideal. Military campaigns in Spain and Germany underscored the empire’s reliance on force to secure its borders and assert its dominance. Despite these contradictions, Augustus’ rhetoric of peace resonated throughout the empire, laying the groundwork for the Pax Romana that would define the first two centuries of the imperial era.

Transition from Expansion to Consolidation

The transition from Augustus to Tiberius marked a critical shift in Rome’s imperial strategy. While Augustus pursued territorial expansion, Tiberius emphasized consolidation and defense, signaling a new phase of imperial policy. This approach reflected a growing recognition of the logistical and administrative challenges of maintaining an expansive empire.

Defensive strategies, rather than outright conquests, became the hallmark of the first-century emperors, though exceptions, such as campaigns in Armenia and Britain, demonstrated that Rome remained a force to be reckoned with when strategic interests demanded it.

This era also saw a decline in the direct militarization of Roman society. The establishment of a professional standing army reduced the reliance on citizen soldiers, contributing to a more stable societal structure. This professional military force not only safeguarded the empire but also underscored Rome’s commitment to maintaining the peace it had so proudly declared.

The Ideology of Peace and the Justification of War

Central to the concept of Pax Romana was the Roman belief in bellum iustum, or just war. This ideology provided a moral framework for Roman expansion, portraying military campaigns as both necessary and beneficial to those brought under Roman rule.

The narrative of Rome as a civilizing force spread through its territories, reinforcing the empire’s claims of bringing stability and prosperity to its subjects. This rhetoric was particularly significant in the provinces, where the tangible benefits of Roman rule—roads, aqueducts, and public buildings—served as symbols of imperial benevolence.

Despite its ideological foundations, the Pax Romana was not without its contradictions. Peace was often enforced through military dominance and the suppression of dissent. While the ideals of stability and harmony were celebrated, the reality in many parts of the empire was marked by ongoing tensions and localized conflicts. Nevertheless, the Roman administration’s ability to manage these challenges highlighted its sophisticated approach to governance and control. (Roman Peace: On the Question of Pax Romana, by Vladimir O. Nikishin)

Augustus and the Foundations of Pax Romana

The establishment of Pax Romana, is often heralded as one of the greatest achievements of Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Ida Östenberg in her paper, "From Conquest to Pax Romana: The Signa Recepta and the End of the Triumphal Fasti in 19 BC" delves deeply into the role of Augustus’ diplomatic recovery of the Roman standards from the Parthians in 20–19 BCE as a cornerstone in the transition from the Republic's militaristic ethos to the imperial ideology of peace and stability. Augustus’ efforts were not only a political triumph but also a masterstroke of propaganda that reshaped Rome’s cultural narrative and imperial identity.

The Parthian Standards and Diplomatic Victory

The Roman standards lost in military defeats—most notably in Crassus' catastrophic loss at Carrhae in 53 BCE—had become a symbol of humiliation for Rome. Their recovery by Augustus, without resorting to armed conflict, marked a significant moment in Roman history.

Augustus presented this diplomatic success as a triumph equal to a military victory, reinforcing his narrative of ushering in a new era of peace and stability. This peaceful resolution highlighted a shift in Roman values, aligning with Augustus’ vision for a world governed by Roman order rather than perpetual conquest.

Unlike the violent triumphs of the Republican era, the recovery of the standards symbolized Roman dominance achieved through diplomacy and negotiation, a hallmark of the imperial ideology under Augustus. By portraying the Parthians as participants in Rome’s peace rather than defeated enemies, Augustus effectively transformed a military embarrassment into a cornerstone of Pax Romana.

The Parthian Arch: A Monument to Peace

In recognition of this achievement, the Parthian Arch was erected in the Roman Forum. This monument not only celebrated the return of the standards but also marked the end of the Republic’s triumphal traditions. Inscribed on the arch were the Fasti Triumphales, a comprehensive list of Roman triumphs concluding in 19 BCE with the triumph of Cornelius Balbus. By ending the list at this date, Augustus signaled the close of the era of endless Republican wars and the beginning of a new age of peace.

The Parthian Arch, strategically placed near other significant monuments in the Forum, symbolized Augustus’ role as the restorer of Roman honor and peace. Its iconography emphasized diplomacy over war and presented Augustus as the mediator of harmony, an image that resonated with his self-styled position as the “Father of the Fatherland” and protector of Roman values.

The recovery of the standards and the subsequent celebration were part of a broader cultural shift orchestrated by Augustus. His reign marked a deliberate move away from the Republic’s militaristic ethos and towards a vision of Rome as a stable and prosperous empire. This shift was evident in his refusal to hold a traditional triumph for the standards’ return.

Instead, Augustus chose subtle and calculated displays of his achievements, positioning himself as the harbinger of peace rather than the conqueror of enemies. This shift was further solidified through monuments like the Ara Pacis, the Altar of Peace, which symbolized Rome’s prosperity and divine favor under Augustus’ rule. The altar, along with the Parthian Arch, encapsulated the ideological framework of Pax Romana, promoting the emperor as the source of stability and order.

Augustus as the Founder of Pax Romana

Augustus’ ability to integrate his diplomatic successes into a broader narrative of peace was a cornerstone of his reign. The Parthian standards’ recovery allowed him to pivot from the chaos of the late Republic to a new imperial order. By emphasizing diplomacy, Augustus crafted an image of Rome as a civilized and benevolent power, contrasting it with the turmoil of the preceding civil wars.

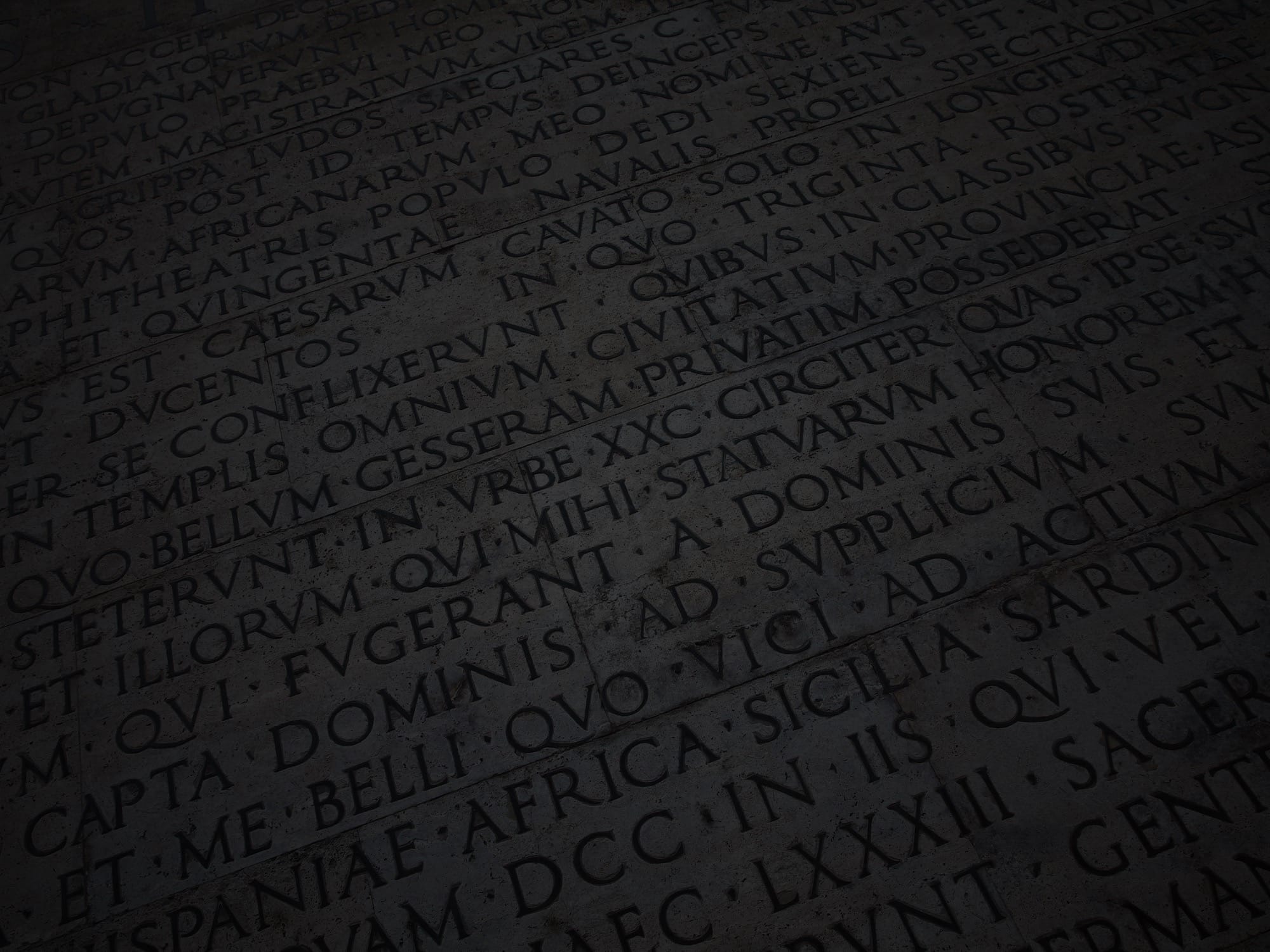

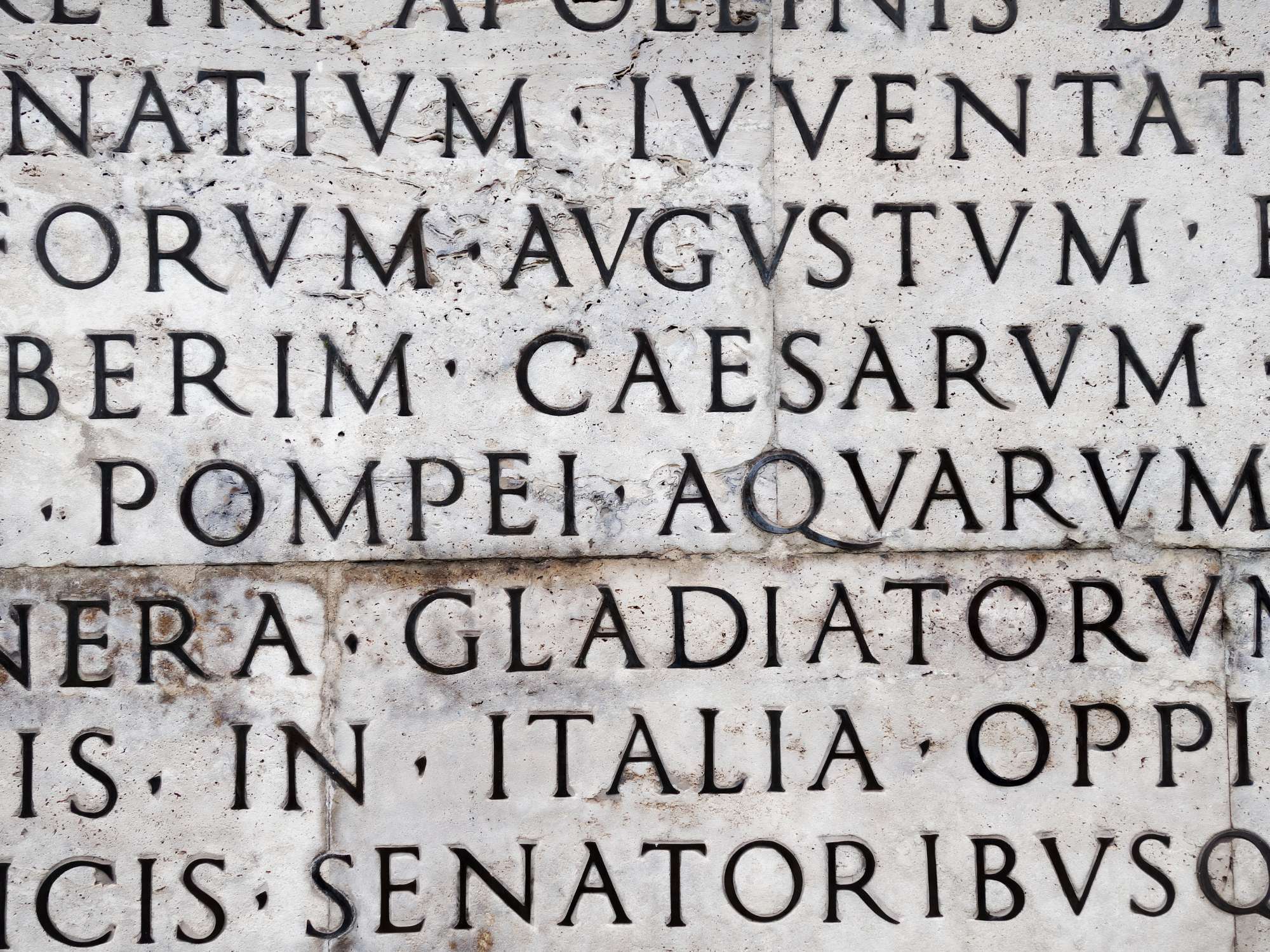

"I restored liberty to the republic, which had been oppressed by the tyranny of a faction ... [and] when I had extinguished the flames of civil war ... I transferred the republic from my own control to the will of the senate and the Roman people."

Augustus, Res Gestae I and XXXIV

The Pax Romana, as embodied by Augustus’ policies and propaganda, was not merely the absence of war but a deliberate reimagining of Rome’s role in the world. It was a peace predicated on Roman supremacy and control, legitimized through Augustus’ careful cultivation of his image as a just and prudent ruler.

A New Narrative of Imperial Power

Ida Östenberg’s analysis reveals how the recovery of the Parthian standards became a symbol of the transition from conquest to consolidation. The use of monuments and cultural messaging transformed the narrative of Roman imperialism. Augustus’ reign was depicted as a golden age where diplomacy and governance replaced the need for constant warfare.

This narrative, immortalized in monuments, literature, and art, established Augustus as the architect of a new world order, one where Rome’s dominance was unquestioned and its peace eternal.

A statue of Roman Emperor Augustus. Credits: FooTToo from Getty Images, by Canva

The recovery of the Parthian standards and the subsequent celebrations were far more than political or military victories—they were the foundation upon which Augustus built his vision of Pax Romana. The Parthian Arch and the Ara Pacis symbolized a profound transformation in Roman culture and governance, one that would define the empire for generations.

By weaving diplomacy, symbolism, and propaganda into a cohesive narrative, Augustus laid the groundwork for an imperial ideology that celebrated peace as the ultimate expression of Roman power. This reinterpretation of Roman supremacy, as Östenberg shows, was a defining moment in the history of the empire and the enduring legacy of Augustus’ reign.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: