What was a Tribune in Ancient Rome?

Tribune was the title of various elected officials in Ancient Rome, but since the term is a bit convoluted and lost in time, the answer to the question is not a simple one.

The term "tribune" (from the Latin tribunus) originally might have only referred to military leaders of Roman tribes (tribus), but over time, it came to represent various political and military offices. Given its extraordinary and spontaneous rise to prominence, combined with the extensive social and political reforms it accomplished, it is no wonder that the Roman tribunate has captured the attention of modern political theorists.

The Roman tribunate has been described as a mechanism of formally sanctioned opposition, designed to critique and challenge government policies without being directly involved in governing. It has been likened to the concept of an institutionalized opposition, created to ensure a balance of power and accountability within the political system.

The Roman Tribunate and Modern Opposition

Bertrand de Jouvenel (a French philosopher, political scientist, economist and diplomat, known above all as a precursor of prospective, an approach dedicated to the study of possible futures, based on information, analysis and projections) highlights the Roman tribunate's significance as a force for preventing abuses rather than exercising power.

He draws on Labeo's (a tribune of the plebs in 196 BC) perspective that tribunes existed to oppose injustices and defend citizens without seeking to govern themselves. De Jouvenel argues that effective opposition should safeguard individual rights and laws without succumbing to the corrupting influence of power.

This philosophy underpins his view that "a power should exist that checks power, without replacing it," emphasizing the tribunate's role in defending the people without aspiring to authority. De Jouvenel challenges the traditional two-party system as the ideal framework for opposition, which suggests opposition must aspire to govern to be constructive and responsible. Instead, he critiques this notion, arguing that such opposition often remains superficial and fails to secure true liberty.

As an alternative, he advocates for institutional mechanisms with the "power of prevention," akin to the ius auxilii of the Roman tribunes, where dedicated public officials act as "social advocates," responding to citizens' appeals against governmental overreach. This approach, he contends, embeds opposition into the structure of liberty itself rather than treating it as a token of democratic consent.

Beyond Prevention: The Dynamic Role of the Roman Tribunate

The Roman tribunes, while serving as a counterbalance to state power, do not fully support the argument for structural opposition in the modern sense. Though the tribunate acted as an opposition force, seeking legitimacy through procedural methods and arbitration rather than violence, it lacked the framework of modern party politics and did not aim to form a government.

However, the institution was far more dynamic than a simple "power of prevention." Tribunes often extended their role significantly beyond oversight.

- First, many tribunes sought leadership within the Roman community, moving beyond their designated status as subordinate officials.

- Second, while the tribunician authority (tribunicia potestas) was distinct from the sovereign power of state (imperium), the tribunes exercised substantial legislative influence.

- Finally, addressing systemic issues like class-based discrimination and oppression required more than a mere review of state actions; it necessitated genuine power to drive social transformation.

The Tribunes and the Fight for Plebeian Representation

While the tribunes did not wield the formal imperium—the official authority of established magistrates—they often used their extensive "self-help" powers to significant and sometimes disruptive effect. During the early stages of the Conflict of the Orders, when the plebeian class faced systemic oppression and exclusion from political office, the tribunes championed the cause of opening priesthoods and magistracies to plebeians.

This struggle, compounded by the economic challenges faced by the plebs, led to a decade of tribune-led turmoil beginning in 376 BCE. During this period, leading tribunes, repeatedly re-elected to office, incited public unrest and obstructed the election of patrician magistrates, declaring that if plebeians could not become consuls, there would be no consuls at all.

Their efforts eventually succeeded with the enactment of a law requiring that one of the two consuls be a plebeian. The first plebeian consul, Sextius, had been a tribune and key leader in this battle for representation. Following this victory, many tribunes subsequently rose to the consulship, establishing the tribunate as a recognized stepping stone toward higher office.

Champions of Reform and Political Power

The Roman tribunate evolved from a modest role focused on preventing abuses of power into a formidable institution that rivaled the authority of the state in civil affairs. Originally centered on the ius auxilii, or the right to aid citizens, this "power of prevention" expanded into a comprehensive arsenal of rights, including the ius intercessionis, or the power to veto official acts.

The veto allowed tribunes to block magistrates’ decrees, legislative proposals, and senatorial decisions, effectively giving them significant control over the political process. Beyond the veto, tribunes assumed proactive powers through the ius cum plebe agendi, enabling them to convene the plebeian council (concilium plebis).

While initially limited to addressing plebeian grievances, the council began influencing state policies during the prolonged Conflict of the Orders. Resolutions passed by the council, known as plebiscites, gained increasing weight, pressuring patrician authorities to adopt them to avoid civil unrest.

This culminated in the lex Hortensia of 287 BCE, which declared that plebiscites would hold the force of law, ending the legal and political discrimination between patricians and plebeians. Through these developments, tribunes secured an essential role in Roman governance. Their legislative initiatives and reforms, particularly during the struggle between the orders, redefined the constitutional structure of the Republic, solidifying their legacy as key architects of equality and political transformation.

Advocates for the People and Catalysts for Change

The Roman tribunate arose as a response to the extreme social and economic oppression faced by the plebeians in the early Republic. The plebs, excluded from political power and subjected to harsh laws and poverty, turned to collective action, including secessions, to demand representation and rights.

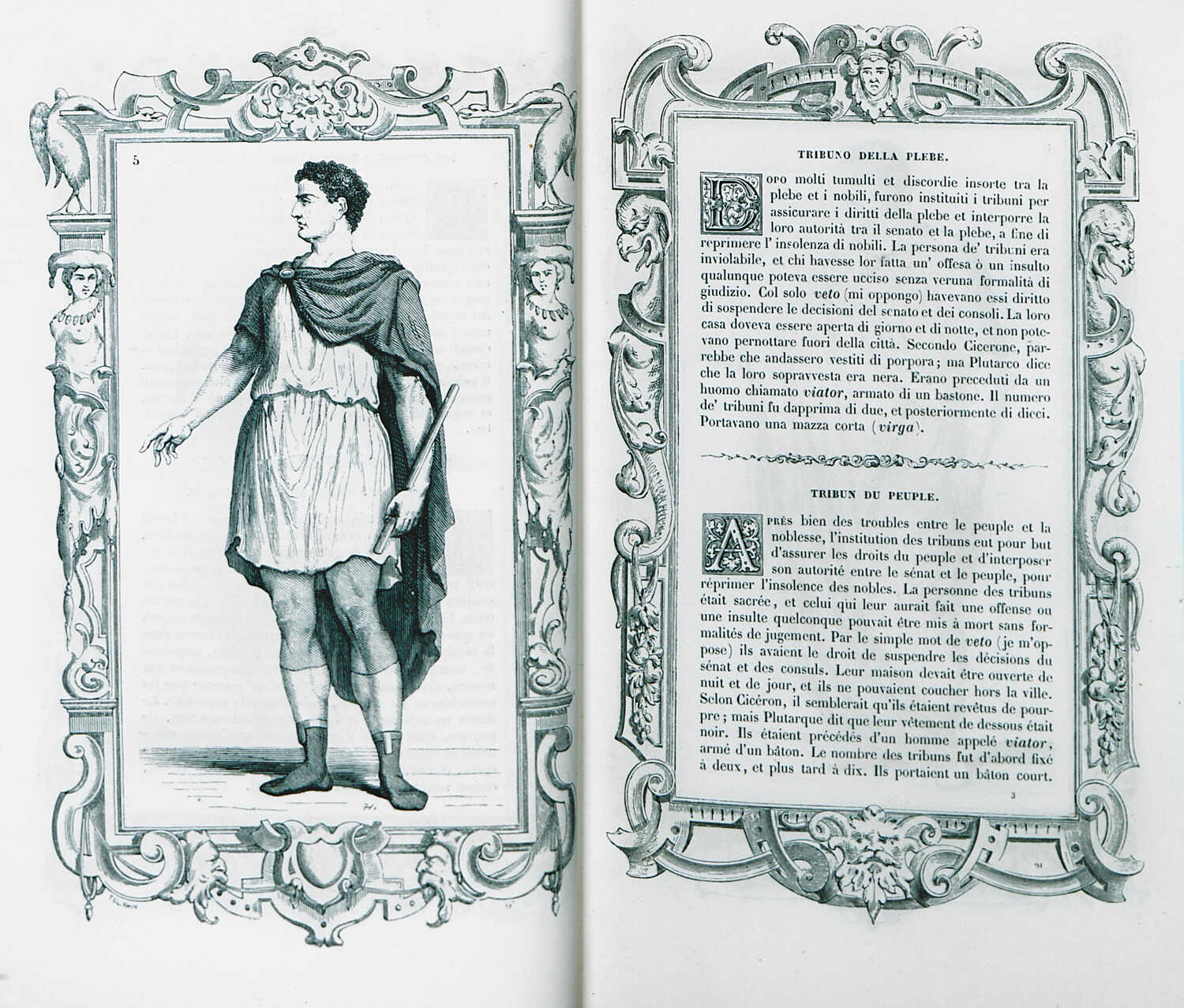

The tribunes, endowed with sacrosanctity and backed by the plebeians’ oaths, became their champions, initiating reforms that transformed Roman society.

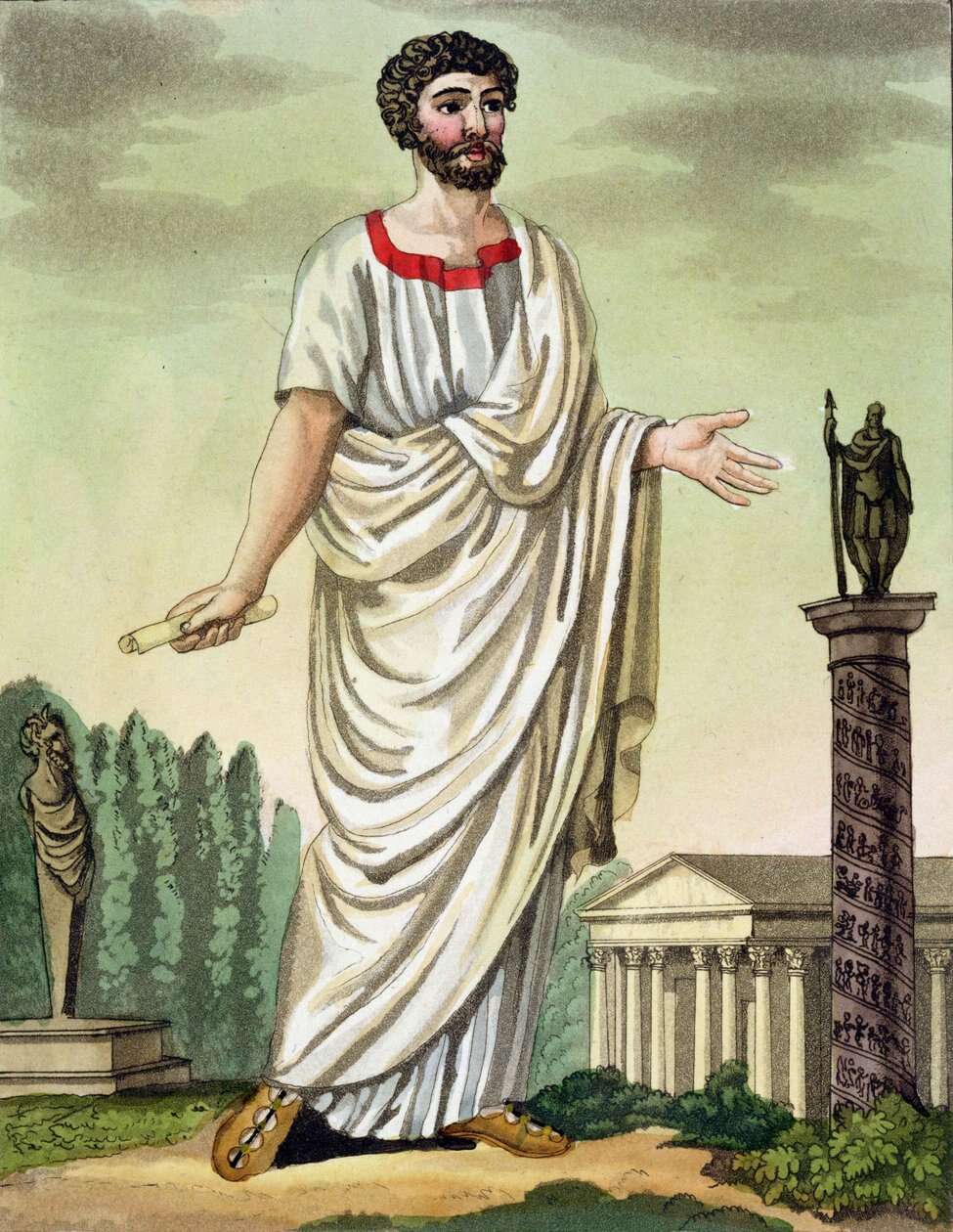

A sketch of a Roman tribune of the plebs, by Cesare Vecellio. Public domain

Initially wielding the ius auxilii, or the right to protect citizens, the tribunes expanded their powers to include the veto and the ability to convene plebeian assemblies. These powers enabled them to push for major constitutional reforms, including the codification of laws in the Twelve Tables, the repeal of intermarriage bans, and the eventual elevation of plebiscites to the status of laws through the lex Hortensia.

Economic reforms also followed, including measures to distribute land, regulate debts, and abolish debt-based slavery. Despite their constitutional advancements, the tribunes’ powers often clashed with the patrician-controlled Senate and consuls, leading to periods of tension and revolution, most notably during the activities of the Gracchi brothers.

While Cicero later characterized the tribunate as a source of sedition, historical evidence suggests that tribunes sought to resolve plebeian grievances through constitutional means. Ultimately, the Republic’s inability to manage internal dissent and balance power contributed to its collapse.

The tribunate, while instrumental in advocating for plebeian rights and reform, also highlighted the Republic’s systemic weaknesses, paving the way for the revolutionary period that culminated in the establishment of the Roman Empire. (Responsible and Irresponsible Opposition: The Case of the Roman Tribunes, by Graham Maddox)

The Early Roman Republic: The Evolution of Governance and the Rise of the Plebeian Tribunate

The governance of early Rome following the expulsion of the monarchy was marked by a period of gradual development and adjustment rather than the immediate establishment of a structured republican government. Contrary to traditional accounts, which suggest a smooth transition to a dual-consul system, the early Republic lacked a centralized magistracy.

Instead, governance was fragmented, with priests exercising judicial authority, minor officials handling administrative tasks, assemblies managing legislative functions, and patrician clans wielding significant control over military and rural affairs. The plebeian tribunate emerged in this context as a vital institution to address the widespread grievances of the plebeian majority, including debt, social oppression, and exploitation by patricians.

Tribunes, protected by their sacrosanctity and empowered by the plebeian oath to defend them, became influential figures in the city, using their authority to veto actions, convene plebeian assemblies, and advocate for social and political reforms. Over time, the tribunes' powers expanded, making them the most significant civilian magistrates in the early Republic, while consuls and praetors focused primarily on military responsibilities outside the city.

This decentralization of authority allowed the Roman government to evolve organically, culminating in the eventual formation of the classical republican constitution after significant reforms in 367 BC.

A possible representation of a Roman tribune, speaking to the people of Rome. Illustration: Midjourney

The tribunes' ability to adapt their sacrosanctity for both defensive and offensive purposes helped them counterbalance the dominance of patricians and shaped Rome’s political landscape. This development underscores the tribunes' central role in Rome’s early governance, contrasting sharply with the traditional narrative that emphasizes consular authority. (Plebeian Tribunes and the Government of Early Rome, by Fred K. Drogula, Providence College)

The Complex Origins of the Roman Magistracies and the Tribunate of the Plebs

The origins of Roman magistracies, particularly the tribunate of the plebs, are fraught with methodological complexities and inconsistencies. Historical narratives often rely on fragmentary or speculative evidence, as much of the early documentation was lost, notably in the sack of Rome in 390 BC.

Roman historians likely retrojected their contemporary understanding of magistracies onto earlier periods, creating a more orderly and constitutional narrative than the historical reality. The tribunate of the plebs, established early in the Republic, arose during a period of intense social conflict known as the Struggle of the Orders.

Initially a defensive institution for plebeians, the tribunate was endowed with sacrosanctity, granting tribunes immunity from violence and enabling them to intercede on behalf of citizens. Over time, their powers expanded to include the veto of magistrates’ actions, initiation of legislation, and even prosecutorial authority. These powers were underpinned by the plebeians' collective oath of allegiance, a feature with deep Italic cultural roots.

Scholars debate the reliability of the traditional narrative of the tribunate and the early Republic, with some suggesting that Rome’s transition from monarchy to republican government was not smooth but marked by a series of evolving constitutional experiments. The plebeian tribunate emerged as part of these experiments, reflecting a broader struggle between the patrician elite and the plebeian majority.

The resulting narrative suggests that the Republic was not a singular, unified entity but a series of constitutional adaptations that culminated in the more stable political structures of the mid-fourth century BC. The tribunate’s role and development exemplify Rome’s early political sophistication and the dynamic interplay between its patrician and plebeian classes, revealing an evolving system that laid the groundwork for the later republican constitution.

The Early Tribunate of the Plebs: Historical Origins and Archaeological Insights

The origins of the Roman tribunate of the plebs, though central to early Republican history, are fraught with historiographical challenges and methodological complexities. Ancient sources, including Cicero, Livy, and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, provide accounts that are broadly consistent but vary in detail regarding the office's inception, powers, and evolution.

These accounts often tie the establishment of the tribunate to the first secession of the plebs in 494 BC, where plebeians protested against patrician dominance, seeking legal and social protections. As aforementioned, central to the tribunate was the concept of sacrosanctitas, which protected tribunes from harm and empowered them to veto magistrates’ actions, intercede on behalf of citizens, and legislate within the plebeian assembly.

Modern scholarship however, debates the reliability of these narratives. Some argue for the retrojection hypothesis, suggesting that later historians reshaped early Republican events to reflect a more structured and constitutional origin. Others contend that the tribunate emerged gradually, reflecting a society transitioning from monarchy to a more complex aristocratic-republican system.

Archaeological evidence from sixth and fifth-century Rome supports the notion of a sophisticated and politically self-aware society, capable of sustaining institutions like the tribunate. Critics of the traditional narrative often cite inconsistencies in ancient accounts, such as the varying numbers of early tribunes or the presence of doublets in the historical record.

However, the absence of alternative traditions and the alignment of multiple sources suggest that the tribunate, as a plebeian institution challenging patrician power, was deeply rooted in early Republican realities. Archaeological findings, including public infrastructure and fortifications, indicate a level of social and political organization compatible with the emergence of such an office.

Ultimately, while specific details of the tribunate's early history remain uncertain, the institution’s foundational role in balancing power between plebeians and patricians is well-attested. The tribunate’s significance as a revolutionary yet stabilizing force in the nascent Republic underscores its enduring impact on Roman constitutional development.

The history of the Roman tribunate highlights two key lessons:

- First, when one class is completely dominated by another, a mere right of veto or the ability to prevent specific instances of oppression is insufficient; substantive power is required to transform societal structures and elevate the social, legal, economic, and political status of the oppressed. The tribunes demonstrated that such power could, for a time, be exercised within a constitutional framework, achieving significant progress through peaceful means and fulfilling the original purposes of the office.

- Second, the tribunate illustrates the necessity of integrating such power into the broader system to ensure accountability. The Roman Republic, however, never developed mechanisms for the peaceful transfer of power between factions or classes, a challenge that persists in most systems of governance. While the two-party system offers a model for alternating power between government and opposition, its practical implementation is not without friction.

The tribunate, despite its remarkable role in advancing plebeian rights during the Conflict of the Orders, does not exemplify the effectiveness of a purely preventive power without the ability to initiate change. The tribunes did wield significant powers of initiation, but these were never fully institutionalized or legally grounded through the granting of imperium. As a result, these powers ultimately became tools for destabilization and anti-system confrontation.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: