Were Christians Really Fed to the Lions in Ancient Rome?

What is the truth behind the phrase: “Christians to the lions?”

Were the Romans really feeding their arena beasts with the first Christians? Was that the capital punishment of the early believers, and were Romans acturally torturing Christians to death?

Christians to the Lions?

The question arises: "Were Christians truly fed to lions during Roman times?" Tertullian, in his Apologeticum, reflects the popular sentiment of the era:

"If the Tiber reaches the walls, if the Nile does not rise to the fields, if the sky does not move or the earth does, if there is famine, if there is plague, they cry at once, 'The Christians to the lions!'"

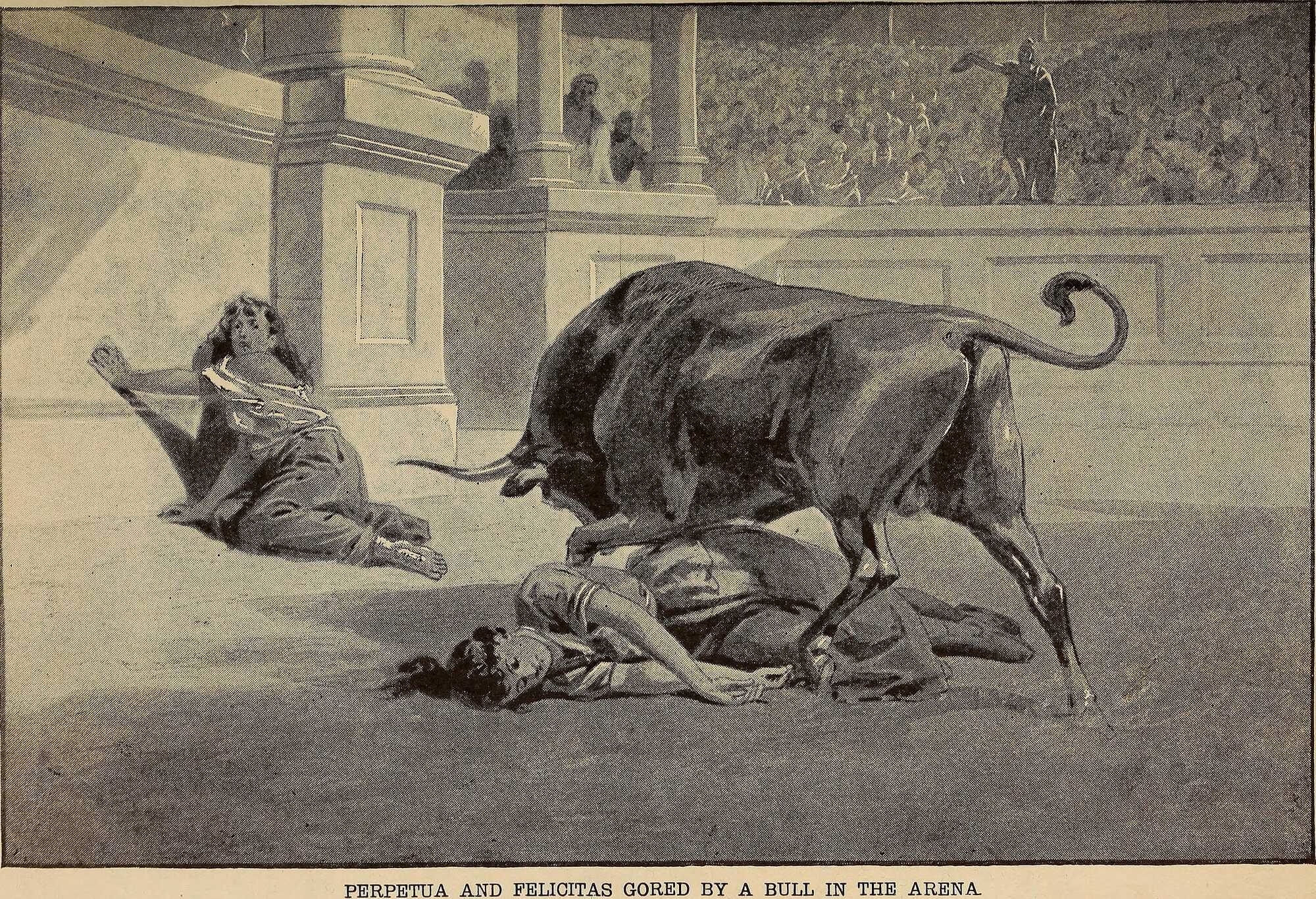

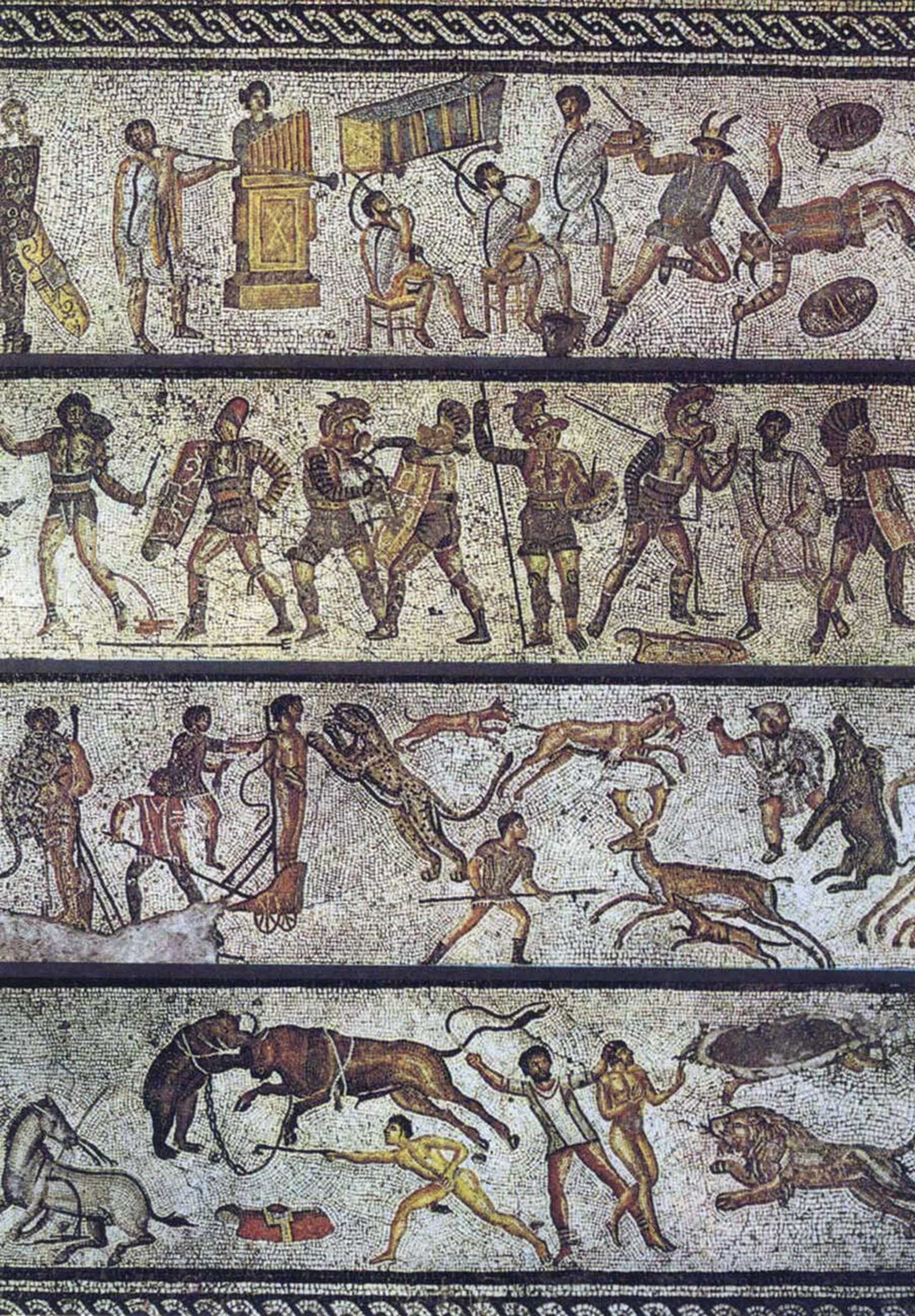

The Passion of the Holy Martyrs Perpetua and Felicity recounts the story of two women—a young noblewoman and mother, Perpetua, and a slave woman, Felicity—who were executed in early third-century Carthage by damnatio ad bestias (condemnation to the beasts). While lions are not explicitly mentioned, the text describes other animals involved in their martyrdom. Historical evidence, such as the Zliten Mosaic, confirms that lions and other large predators were indeed used in Rome to execute criminals and insurrectionists.

It is also clear that Christians were among those condemned to face wild beasts.

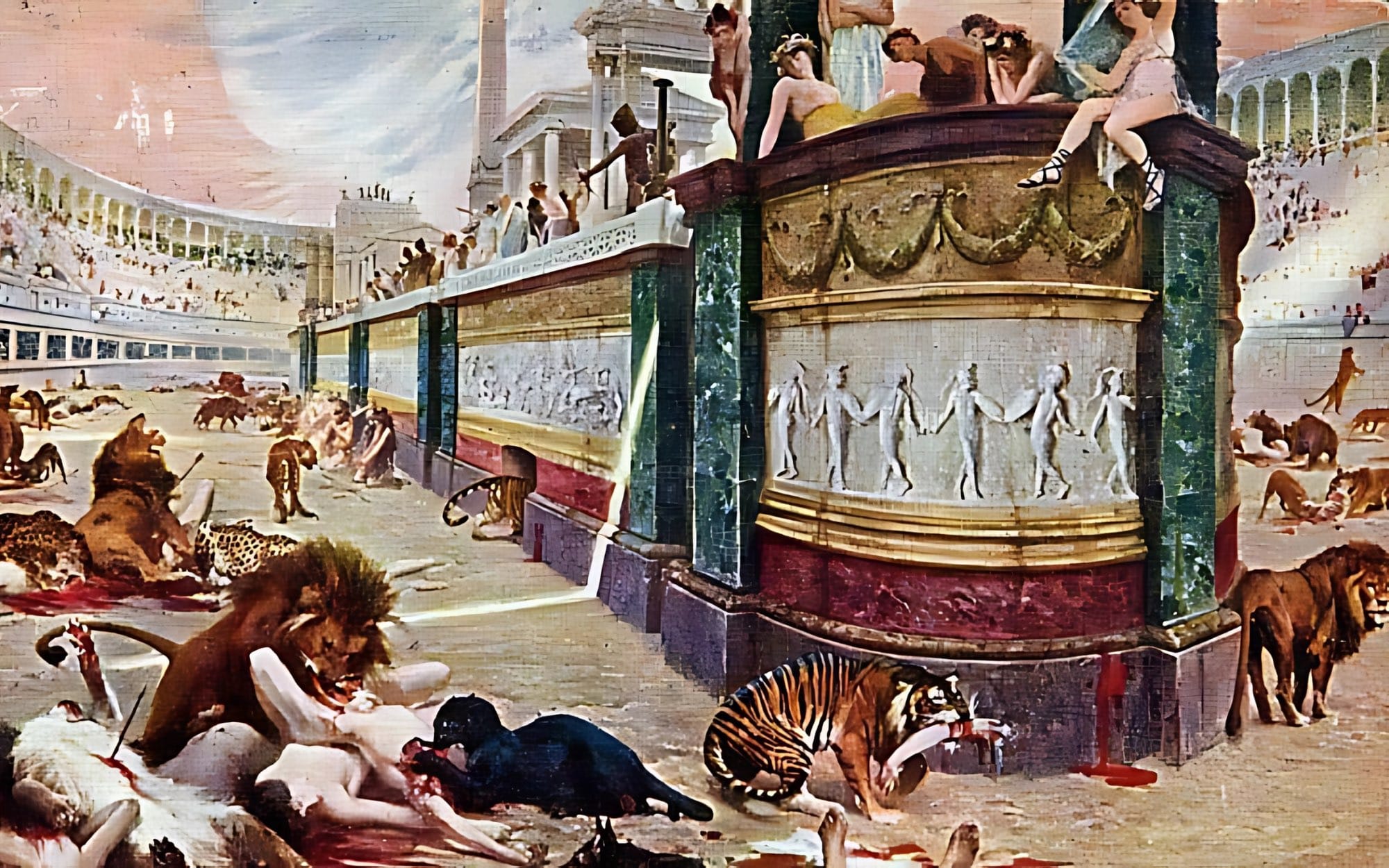

A gravure depicting Perpetual and Felicitas gored by a bull in the arena. Public domain

However, the scale of the practice and the specific animals involved remain subjects of scholarly debate. Christians faced many forms of execution in the Roman Empire. Eusebius, in his De Martyribus Palestinae, documents that Urbanus, governor of Palestine, employed diverse methods of persecution, including burning, drowning, exposing martyrs to beasts, forcing youths into gladiatorial combat, and other forms of torture and imprisonment.

Maybe the question should be: "Did Christians face persecution as portrayed by modern Christian teachings?" This question holds merit, as Christian tradition often emphasizes that early Christians endured significant persecution. Images of martyrdom and being thrown into gladiatorial combat are frequently brought up when people are asked what they imagine the early years of Christianity were like.

However, this perspective is not the most accurate interpretation and is not widely accepted among scholars today.

Historian Candida Moss explores this topic in her book, “The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom”. Moss, a professor of New Testament Studies at Notre Dame, argues that widespread persecution of Christians, as commonly imagined, is a myth.

She presents evidence showing that out of over 250 years of early Christian history, no more than 12 years saw significant, Empire-ordered persecution—and none of these occurred during the first century, when Christianity was still emerging.

In its earliest decades, Christianity likely went relatively unnoticed. By 70 CE, small churches had appeared across the eastern Mediterranean and even in Rome, but these groups were too small to attract serious attention or opposition. Moss suggests that widespread persecution wasn’t plausible at this stage, as Roman authorities were unlikely to even be aware of Christianity’s existence.

It was only as Christianity grew in popularity, likely by the late first century, that Christians began to face harsher criticism. Even then, most early Christians experienced more social scorn and dislike—similar to the treatment of Jews outside the Levant—than direct persecution.

The author emphasizes that "the vast majority of Christians never stood before a Roman judge, paid a fine, or experienced torture." While there were localized instances of persecution in some regions of the Empire, these were exceptions rather than the rule.

She further notes that during the first century, Roman emperors likely weren’t even aware of Christians as a distinct group. As she puts it, “For almost all of the first century, it’s unclear that Roman emperors even knew that Christians existed." Without awareness of their existence, the Roman state had little reason to actively persecute Christians.

Persecution and Myth: Reevaluating Early Christian Suffering in the Roman Empire

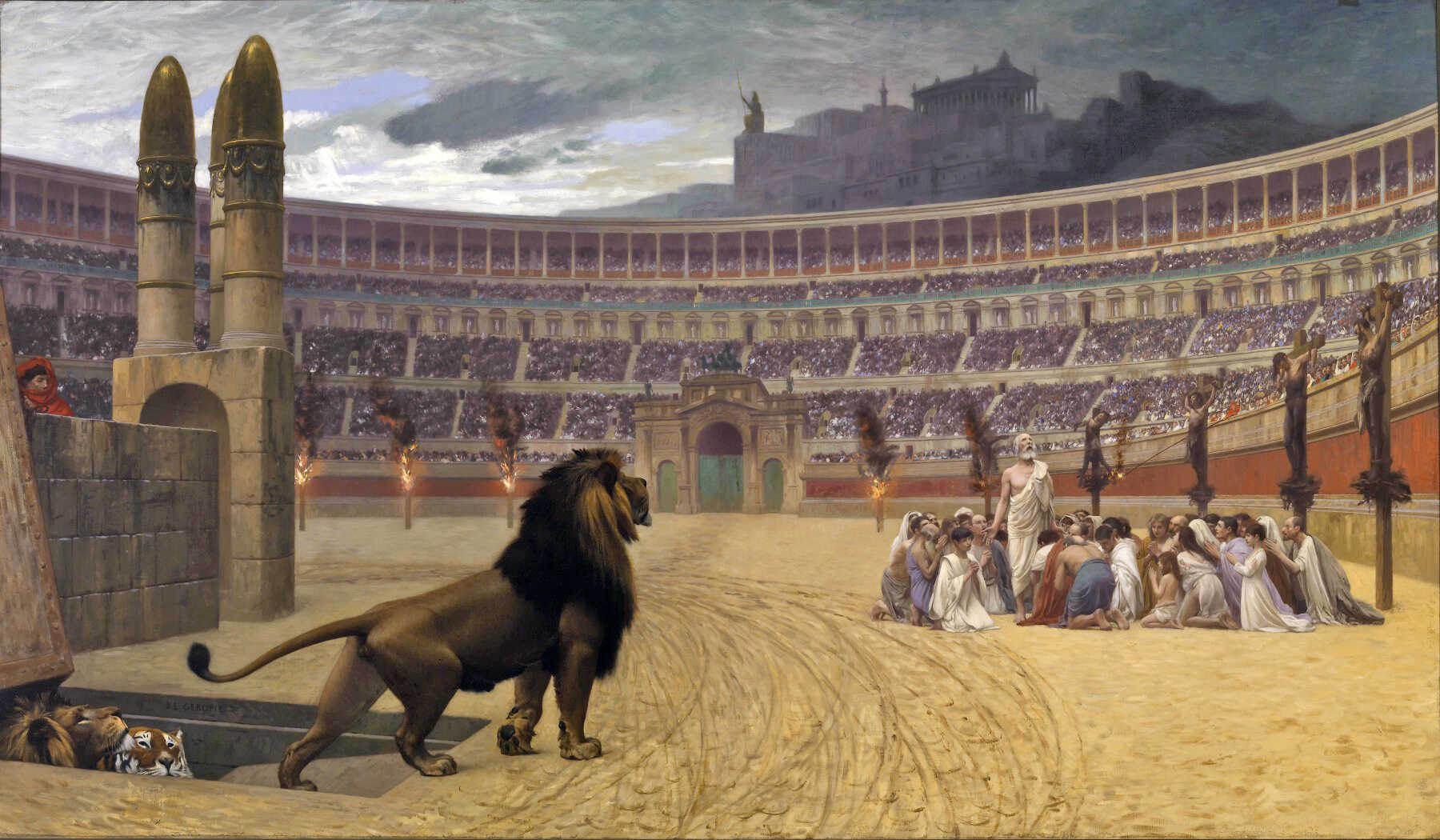

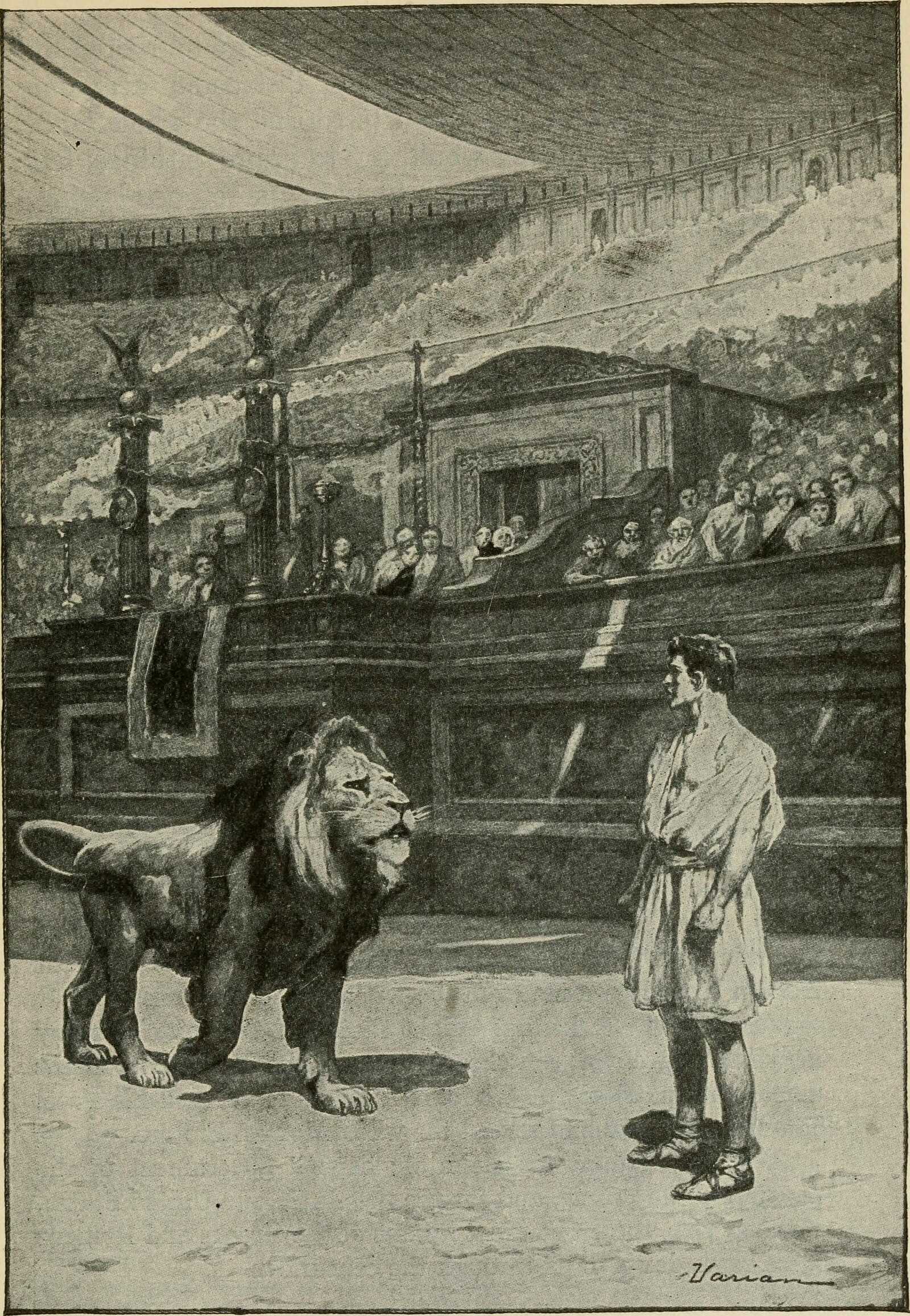

Moss says that when considering the experiences of Christians under Roman rule, many immediately envision dramatic scenes of persecution: Christians being thrown unarmed into amphitheaters to face lions, burned alive, or executed in ways that epitomize cruelty and sadism.

These images often include hostile Roman crowds delighting in their suffering, with Christians depicted as meek, devout, and constantly fearful of arrest and execution. This narrative has been deeply ingrained in two millennia of literature, art, and modern media, from Ben Hur to The Passion of the Christ. The image of Christians living in fear, secretly meeting in catacombs, and communicating through covert symbols like the fish remains ubiquitous.

However, the reasons for this supposed persecution are less clear to many. Popular belief suggests Christians were targeted because of their distinctiveness, their devout nature, or simply the fear and jealousy of their Roman persecutors. Early Christian accounts themselves, such as those from Justin Martyr and Tertullian, emphasize this narrative.

Justin, writing in the second century, claimed that Christians were condemned merely for their identity as Christians. Tertullian famously noted that any disaster in Rome—from floods to famines—was blamed on Christians, with cries of "The Christians to the lions!" echoing through the city.

This story of persistent and brutal persecution has been repeated across generations, creating a deeply entrenched narrative of continuous suffering. Yet, this perspective warrants scrutiny. How many Christians were truly martyred? And why were they targeted at all?

She explores the evidence for violence against Christians in the early church and the reasons behind it. While Christians were certainly not a beloved group in Roman society and were often disliked, they were not perpetually hunted or regularly subjected to imperial persecution. In some cases, actions that led to Christian executions were not even specifically directed at them.

Focusing only on periods of persecution can exaggerate the impression that Christians were constant targets. Moss specifically examines periods of persecution, revealing that state-driven measures against Christians were relatively rare and often limited in scope. Historically, four major periods of persecution are often cited:

- The aftermath of the Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE

- The reign of Emperor Decius around 250 CE

- A brief period during Emperor Valerian’s reign (257–258 CE)

- The “Great Persecution” under Emperor Diocletian (303–305 CE), later renewed by Maximinus Daia (311–313 CE)

Even with these events considered, imperial actions against Christians lasted fewer than ten years across nearly three centuries. Scholars like Geoffrey de Ste. Croix argue that no evidence supports Roman governmental persecution before 64 CE. The classification of these events as persecution often depends on perspective, as many incidents were localized and limited in duration.

Punishment as Public Spectacle in Ancient Rome

In his Apologeticum, Tertullian vividly describes the grim theatricality of Roman punishments, recounting incidents where individuals were burned alive as Hercules or castrated as Attis. These macabre spectacles, which he termed "fatal charades," blended execution with role-playing in a dramatic public setting, often featuring elaborate recreations of mythological scenes.

Roman Penal Aims and Practices

Punishment in ancient Rome was deeply intertwined with cultural, social, and political frameworks. Unlike modern systems, which emphasize reform and deterrence, Roman penalties served a complex mix of purposes, including retribution, humiliation, and deterrence. Public executions and punishments were designed not just to punish offenders but also to communicate societal norms and enforce authority through spectacle.

Seneca acknowledged that punishment often aimed to satisfy vengeance or reassert the status of victims. For example, crimes like arson were met with execution by fire, adhering to the principle of talio ("an eye for an eye"). Similarly, fraudulent money-changers had their hands amputated, a penalty that combined retribution, humiliation, and deterrence.

Humiliation played a pivotal role in Roman punishments. Publicly shaming the offender served to alienate them from their community and validate the state’s authority. High-profile punishments, like those of Jesus, often included mockery as a means of reinforcing societal hierarchies. The humiliation was sometimes enhanced through theatrical elements, as seen in the soldiers’ mocking of Jesus with a crown of thorns and a purple robe, parodying the regalia of Hellenistic rulers.

Public displays of punishment were central to the Roman penal system. Executions often took place in amphitheaters or other highly visible locations to maximize their deterrent effect. The intent was to inspire fear among spectators while ensuring the audience derived a sense of moral superiority.

This dynamic explains why executions were often elaborate affairs, blending horror and entertainment. Roman philosophers like Seneca and Taurus acknowledged deterrence as a key objective of punishment. The gruesome spectacles served as a warning, with the public setting reinforcing the consequences of deviant behavior.

However, the theatricality of these events also distanced spectators from the reality of suffering, turning punishment into a form of popular entertainment. Fatal charades elevated Roman punishments to an extraordinary level of theatricality.

Offenders were forced to play mythological roles that mirrored their crimes. For example, arsonists might be burned alive as Hercules, and others might reenact stories from mythology before their execution. These performances were meticulously staged, with the dual purpose of delivering justice and entertaining the masses.

The charades capitalized on Roman society’s fascination with drama and myth, transforming executions into grand public spectacles. The audience's pleasure derived from witnessing the offender’s suffering was integral to the event, reflecting the cultural norms of the time.

Correction, Prevention, and Justice

Though retribution and deterrence dominated Roman punishments, the concept of correction was not entirely absent. Philosophers like Plato and Seneca suggested that punishment should aim to reform offenders, though this idea rarely influenced actual practices. More commonly, punishments sought to prevent repeat offenses by physically incapacitating criminals or removing them from society altogether. (Fatal Charades: Roman executions staged as mythological enactments, by K. M. Coleman)

The Legal Foundations of Christian Persecution in the Roman Empire before 250 CE

The persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire before 250 CE has long been a subject of fascination and debate among historians. T.D. Barnes’ “Legislation against the Christians”, sheds light on this complex topic, challenging traditional narratives and revealing a nuanced picture of the legal and social frameworks that governed early Christian prosecutions.

By examining the primary evidence, Barnes dismisses many misconceptions and provides a clearer understanding of how and why Christians were targeted during this period. Barnes begins by emphasizing the absence of explicit legal enactments against Christians in the early years of the Roman Empire.

Contrary to common assumptions, there is no evidence of a definitive senatus consultum or imperial decree that declared Christianity illegal.

A painting by Jan Styka, depicting the Christians thrown to the lions. Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

For instance, Tertullian’s claim that Emperor Tiberius advocated for Christianity in the Senate and sought to integrate it into the Roman Pantheon is based on unreliable sources. This narrative, often repeated in later traditions, lacks corroboration and cannot be taken as historical fact.

The infamous persecutions under Emperor Nero, following the Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE, illustrate the ad hoc nature of early Christian prosecutions. Nero did not persecute Christians because their faith was inherently criminal but rather used them as scapegoats to deflect blame for the disaster.

According to Tacitus, Christians were labeled as arsonists and subjected to brutal punishments, satisfying the public’s demand for retribution. This event marked the beginning of Christians being associated with criminality in the public eye, though it was not rooted in a broader legal framework.

Subsequent emperors approached the question of Christianity with varying degrees of pragmatism. Emperor Trajan’s correspondence with Pliny the Younger offers a revealing glimpse into early imperial attitudes.

Pliny, as governor of Bithynia, sought guidance on how to handle Christians in his jurisdiction. Trajan responded with a policy of restraint: Christians were not to be actively sought out but could be punished if openly accused and if they refused to recant. Those who renounced their faith and performed acts of sacrifice to Roman gods were pardoned. This approach focused on public conformity rather than religious suppression, illustrating the absence of a systematic legal strategy against Christians.

Under Emperor Hadrian, this cautious approach continued. His rescript to Minicius Fundanus, proconsul of Asia, discouraged frivolous accusations against Christians and emphasized the importance of due process. However, while this decree provided some measure of protection, it did not eliminate the threat of persecution, as accusations could still be weaponized by individuals seeking to exploit social or political grievances. The precarious status of Christians remained unchanged.

During the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the persecution of Christians intensified sporadically, particularly in regions like Gaul. Local governors and public sentiment often played a significant role in these episodes, rather than direct imperial directives. Barnes highlights that these events were driven more by regional dynamics than by a coordinated policy from Rome. This pattern underscores the decentralized nature of Christian persecution in the early Empire.

The period of the Severan dynasty presents further ambiguities. Septimius Severus is often credited with issuing an edict that prohibited conversions to Christianity and Judaism. However, Barnes argues that the evidence for this edict is tenuous at best. Christians during this period were still prosecuted primarily for their identity rather than for acts of conversion. The narrative of Severus’ alleged edict likely stems from later interpretations rather than contemporary records.

Barnes concludes that Christian persecution in the Roman Empire before 250 CE was neither systematic nor uniformly enforced. Instead, it was shaped by episodic imperial policies, regional authorities’ discretion, and societal prejudices.

Christians were prosecuted, but not as part of a coordinated effort to exterminate their faith; it was done as a means of maintaining social order and suppressing perceived deviance. These prosecutions reflected broader Roman concerns about unity, tradition, and conformity rather than targeted religious animosity.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: