Was Divide and Conquer a Julius Caesar Invention, or Not?

Julius Caesar knew how to eliminate enemies and how to "read" military intelligence, two of his most important traits.

Divide and rule, or divide and conquer, in political and social contexts, refers to the tactic of gaining and maintaining control by fragmenting opposition. This involves taking advantage of existing divisions within a political group or community by adversaries, or deliberately creating or exacerbating such divisions to weaken unity and prevent collective action against the ruling power.

Who was the first to use Divide and Conquer?

The divide and conquer (or divide et impera) strategy has ancient roots and is not attributed to a single individual, but rather evolved over time as a common military and political tactic. However, some of the earliest documented uses of the strategy are found in the Roman Empire, notably by Julius Caesar during his conquest of Gaul. Caesar skillfully exploited divisions among the Gallic tribes to prevent them from uniting against him, weakening their resistance and enabling Roman control.

The concept of divide and conquer can be traced back to Philip II of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great. Philip used this tactic to subdue the Greek city-states, playing them against each other to strengthen his own position. The idea was to fragment larger, unified opposition by encouraging infighting or exploiting internal divisions, making it easier to dominate smaller, weakened factions.

In essence, while Julius Caesar is often closely associated with this strategy, it was already in use by leaders like Philip II of Macedon and likely developed even earlier in human history, applied to both military and political arenas.

Also, Caesar’s own writings, such as Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War), were used to shape public perception of his campaigns, portraying him as a hero and justifying his actions. This was a form of propaganda that bolstered his political position in Rome.

Caesar’s Triple Role

Caesar, famous for his military expertise and numerous conquests, was a Roman statesman, general, and writer who played a key role in the expansion and defense of Rome's borders. He famously conquered Gaul (modern-day France and Belgium) while simultaneously safeguarding the Roman Empire.

His success, widespread popularity, and defiance of the Senate stirred both admiration and fear among his allies and adversaries. Caesar recognized that to ensure his survival and that of the Roman state, he had to embrace both defensive and offensive strategies, striking decisively against any threats to his personal ambitions and to Rome.

Caesar understood the gravity of his position and recognized that true authority cannot be dismissed, faked, or trivialized with empty words disguised as truth.

Julius Caesar’s Bust. Credits: iirraa, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

‘He knew that wielding power required self-respect, and failing to exercise it would erode the trust of citizens, leaving them in distress. Although often seen as nearly omnipotent, especially after his death and deification, which blurred the lines between human and divine in the decline of ancient freedom, Caesar was keenly aware of his limitations—those natural boundaries that, while implicit, could not be crossed without consequence.

Unlike many leaders, Caesar was capable of justifying his actions and words, though his explanations were difficult to grasp, as they were written with the belief that nothing should be clarified beyond what the reader could see for themselves. This approach has led some to describe his writings as cold. Unadorned and seemingly straightforward, his works have often been read by those least likely to fully understand them, such as young students.

Yet, even in such conditions, his controversial legacy as one of the most impactful figures in the West shines through—though not easily articulated, he did his legacy justice.

Eliminating Enemies

Caesar employed three key strategies to deal with his adversaries, ensuring his dominance in ancient Rome and securing victories that elevated Rome's status over other nations.

- First, he sought to build alliances and coalitions, which, although temporary, proved highly advantageous in the short term.

- Second, he employed a defensive-offensive approach, taking the fight directly to his enemies. This is famously demonstrated when he crossed the Rubicon, declaring "the die is cast," and again when he pursued Cato to Utica, where Cato chose suicide over facing defeat at Caesar’s hands.

- Third, Caesar utilized a rapid, direct confrontation strategy, often attacking his enemies head-on without delay. This decisive approach, sometimes called the "Gadarene" strategy, saw him confronting opponents swiftly and without hesitation.

Image Credits

#1: Dorotheum, Author: Giovanni Peruzzin, Public domain

#2: Dguendel, Author: François Duquesnoy, CC BY 4.0

#3: Rijksmuseum, Public domain

Building a Coalition

A coalition is a temporary alliance formed to pursue joint activities or achieve a common goal. It allows members with shared values, interests, and objectives to pool their resources, creating a stronger collective force than they would have individually. Caesar, recognizing this, strategically formed the First Triumvirate to enhance his political power in the Roman Senate and secure higher offices. This alliance significantly bolstered his actions until its eventual dissolution.

For instance, when Bibulus, who served alongside Caesar as Curule Aedile in 69 B.C., attempted to veto Caesar’s land reform bill for Pompey's veterans, the coalition acted in Caesar's favor. Caesar's allies, notably Crassus and Pompey, vocally supported the bill.

Despite Bibulus’ efforts to block the legislation through omens, Caesar's backers resorted to extreme measures, breaking Bibulus' fasces, injuring magistrates, and humiliating him. The purpose of the coalition was clear: to shield Caesar from opposition as he rose to the peak of his political career.

Defensive-Offensive Approach

Caesar utilized both defensive and offensive strategies to fulfill his goals, though he primarily depended on offensive realism due to its effective results. Defensive realism, a concept from structural realism, emphasizes maintaining sufficient power for self-defense, fostering a stable and peaceful existence.

However, during Caesar’s era, a purely defensive strategy was seen as a sign of vulnerability, inviting external threats. Caesar understood that adopting an aggressive posture was essential to maintaining Rome’s strength and securing its position.

While Caesar occasionally used defensive tactics, particularly in attempts to mend his relationship with Pompey, his approach was largely offensive. For instance, after Pompey rejected an alliance through marriage, Caesar didn’t back down but continued pursuing his objectives.

He engaged in multiple military campaigns, both against foreign enemies and domestic adversaries like Bibulus and Cato. His offensive stance was most visible in his conquests in Gaul and his actions against the Roman Senate. By taking the fight to his enemies, Caesar solidified Rome's dominance and expanded its reach, positioning it as a dominant power.

The offensive realism strategy, as outlined by scholars like John Mearsheimer, assumes that in an anarchic international system, great powers must constantly seek dominance to ensure their survival. Caesar exemplified these principles by expanding Rome’s power aggressively, securing it as the dominant state in the region.

His victories brought glory and success to Rome, but his constant offensive strategies left him exposed to internal opposition, which eventually led to his assassination. Augustus, his successor, continued this legacy by carefully balancing offensive actions with more cautious political strategies to ensure Rome’s long-term stability.

Gadarene Style

Caesar dealt with his enemies decisively and without hesitation. Once he set his mind to something, he swiftly accomplished it. A notable early example of this was during his journey across the Aegean Sea when he was captured by pirates.

According to Plutarch, despite being their prisoner, Caesar maintained an air of superiority, promising the pirates that he would hunt them down and crucify them after his release. The pirates mocked him, thinking he was joking. After being ransomed, Caesar fulfilled his threat by raising a fleet, capturing the pirates, and, in an act of mercy, having their throats slit before crucifying them.

Similarly, when called to defend Rome from an eastern invasion, Caesar quickly gathered an auxiliary army and successfully repelled the attack. His swift, determined approach was also evident in his personal life, such as when he divorced his wife, Pompeia, in 67 B.C.

Pompeia, the granddaughter of Sulla, had become an adversary in Caesar's eyes due to rumors of her improper conduct.

Pompeia’s Portrait. Credits: Rijksmuseum, Public domain

Plutarch notes that even though Caesar claimed to have no proof of her infidelity, he divorced her, stating that "Caesar's wife must be above suspicion." By this time, Caesar had grown powerful and eliminated anyone he perceived as an enemy, and Pompeia's rumored misconduct placed her in that category. This decision must have been devastating for Pompeia, as there was no clear evidence against her.

Gaius Julius Caesar's rise to power was marked by challenges from both friends and foes. His approach and strategies played a crucial role in securing his success before his untimely death.

Had Caesar not employed certain tactics, he might have met his demise earlier than 44 B.C. The Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, along with Gaius Marius, who held power before Caesar, could have fared better and lived longer if they had followed his methods. Their advocacy for the masses was something the Senate, controlled by the optimates, could not tolerate.

Caesar, on the other hand, took bold actions to neutralize his opponents, beginning by stripping the Senate of its powers, consolidating authority, and declaring himself dictator. His aggressive stance, especially against Rome's enemies like the Gauls, elevated Rome’s status.

It's also worth noting that Octavian (later Augustus) adopted some of Caesar's strategies, particularly his military tactics, but modified others. Unlike Caesar, Octavian avoided becoming a dictator. As scholars explain, Octavian "retained the constitution as far as was practicable, while securing power to enable him to uphold and prevent a renewal of civil war." He restored some authority to the Senate but remained the ultimate ruler of the Roman world.

After defeating many of his opponents and securing his position, Caesar appeared to adopt a more defensive stance, likely believing his power was no longer at risk. This may explain why he ignored a warning from an ordinary civilian about the ides of March—a warning he might have taken more seriously if it had come from someone like Brutus, a trusted ally, or from a neighboring nation.

Ultimately, Caesar let his guard down at a time when he should have been more vigilant, given the immense power he had accumulated. Further studies might explore Caesar's relationship with his legions and assess the strengths and weaknesses of his rule. (Julius Caesar and His Security Strategy in Ancient Rome, by Monica O.Aneni,Ph.D and E.F.Taiwo, Ph.D)

Caesar’s Famous Divide and Conquer Tactic with the Gauls

Julius Caesar’s mastery of the divide et impera (divide and conquer) strategy was a defining feature of his military success, particularly during the Gallic Wars (58–50 B.C.). Caesar’s brilliance lay in his ability to exploit the internal divisions and rivalries of his enemies to weaken them from within before engaging in direct combat. Gaul, a region fragmented into numerous tribes, each with its own long-standing political and cultural rivalries, provided the perfect environment for Caesar to use this strategy to his advantage.

Rather than facing a unified Gallic force, Caesar astutely manipulated the existing tensions between tribes. By aligning with certain tribes and turning others into enemies, he effectively dismantled any potential for a unified Gallic resistance.

A prime example of this was his alliance with the Aedui, who were rivals of the Helvetii and other tribes like the Averni. Through strategic alliances with the Aedui and other Gallic groups, Caesar isolated more powerful opponents, ensuring that no significant coalition could form to challenge Roman forces.

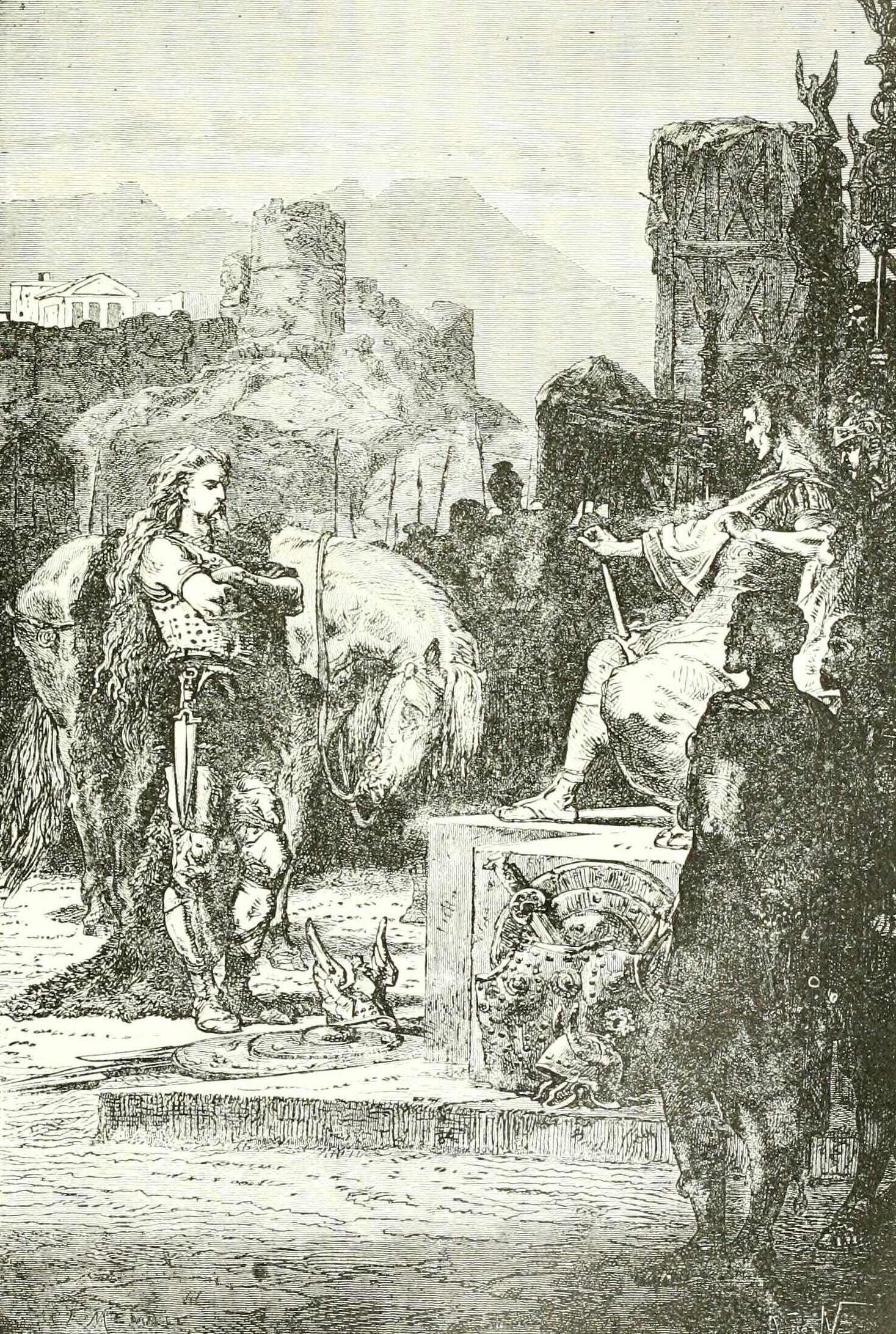

Diplomatically, Caesar excelled at isolating key Gallic factions. He would negotiate with neighboring tribes to deprive his enemies of alliances, weakening their ability to muster strong resistance. His dealings with the Germanic leader Ariovistus illustrate this perfectly: through careful diplomacy and manipulation, Caesar created divisions between the Gallic tribes and the Germanic forces, ensuring that the two groups could not unite against him. This diplomatic isolation was a key aspect of Caesar’s divide and conquer approach, allowing him to confront enemy forces that were already politically and militarily vulnerable.

Another dimension to Caesar’s strategy was his exploitation of internal political disputes within Gallic tribes.

Gaius Julius Caesar Bust. Credits: Andrew Bossi, CC-BY-SA-2.5

He supported Gallic leaders who were favorable to Rome, often aiding those who had been ousted by rival factions within their own tribes. By restoring these leaders to power, Caesar built a network of indebted allies who would act in Rome’s favor, further dividing the Gallic resistance. For instance, the Remi tribe’s allegiance to Caesar during his campaign against the Belgae demonstrated how Caesar’s manipulation of political allegiances enabled him to control key regions without extensive direct military engagement.

Caesar’s divide and conquer tactics also relied on encouraging betrayal and opportunism. He understood that tribal allegiances could be fluid and took advantage of this by encouraging defections and betrayals. Certain tribes, seeing the power and success of Caesar’s campaigns, would switch sides and support the Romans in hopes of gaining favor or avoiding destruction. The Treveri tribe, for example, shifted their loyalties multiple times during the Gallic Wars, showcasing how Caesar’s manipulation of tribal alliances prevented his enemies from uniting into a formidable force.

His use of psychological warfare and propaganda was another vital tool in his divide and conquer strategy. Through his writings in Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Caesar emphasized the disunity of the Gallic tribes and his own alliances, portraying the conflict as a series of isolated victories over fragmented opponents.

This portrayal strengthened his position by creating the perception of inevitable Roman victory, further discouraging Gallic unity. Caesar’s psychological manipulation of both his enemies and potential allies allowed him to maintain control over the narrative of his conquests.

One of the most notable applications of this strategy was at the decisive Battle of Alesia in 52 B.C. Despite the efforts of the Gallic leader Vercingetorix to unify the tribes against Rome, Caesar had already sown the seeds of division throughout Gaul. His previous campaigns had weakened key tribes, and many were either allied with Rome or too fractured to effectively join forces. The result was a Gallic force that, despite its size, could not coordinate well enough to resist Caesar’s siege tactics, leading to a decisive Roman victory and the eventual subjugation of Gaul.

Caesar’s divide and conquer strategy worked on multiple levels—exploiting tribal rivalries, forging strategic alliances, using diplomacy to isolate opponents, and encouraging betrayal and opportunism. His approach was not purely military but was supported by diplomacy and psychological warfare, creating an environment where his enemies could not unite against him.

By pitting tribes against one another and isolating his enemies, Caesar managed to defeat large coalitions of Gallic forces that, if united, might have posed a significant threat to Rome’s control of the region. His use of intelligence and careful manipulation of tribal politics was crucial in ensuring that he faced manageable opposition, a key factor in his military successes throughout the Gallic Wars.

Caesar’s Greatest Skill: The Right Use of Military Intelligence

In his description of Julius Caesar's military expertise and generalship, Suetonius tells us:

"In the conduct of his campaigns it is a question whether he was more cautious or more daring, for he never led his army where ambuscades were possible without carefully reconnoitring the country, and he did not cross to Britain without making personal inquiries about the harbours, the course, and the approach to the island.

But on the other hand, when news came that his camp in Germany was Cbeleaguered, he made his way to his men through the enemies' pickets, disguised as a Gaul" do

Suetonius, Divus Iulius

Julius Caesar significantly contributed to the development and use of the Roman military, but among all his notable military skills—such as leadership, generalship, speed, troop motivation, psychological warfare, and courage—Suetonius highlights one often overlooked by modern scholars: his use of military intelligence. While many scholars tend to ignore this aspect, some do recognize Caesar's exceptional abilities in the realm of intelligence within the Roman army.

Julius Caesar utilized various methods to gather intelligence for his military campaigns, as demonstrated throughout De Bello Gallico. Intelligence took many forms, ranging from reports on enemy traditions, food, clothing, and superstitions to direct observations and strategic insights from allies and scouts.

Caesar’s Intelligence Sources Included:

- Prisoners – For example, when questioning German captives, Caesar learned that their avoidance of battle was tied to superstitions, where their matrons predicted defeat if they fought before the new moon.

- Allies – Caesar often relied on neighboring tribes like the Remi and the Senones, who had deep knowledge of local customs, troop numbers, and strategies. These allies could move undetected and provided crucial information about enemy activities.

- Exploratores (scouts) – These patrols provided tactical intelligence about the enemy’s current position, as Caesar’s forces moved through contested regions.

- Legates' dispatches – Information also came from trusted commanders, such as Labienus, who sent frequent reports about enemy movements while Caesar was wintering in Cisalpine Gaul.

Caesar also sought information from traders when preparing for his invasion of Britain. However, since their knowledge was limited, he sent the tribune Gaius Volusenus on a scouting mission to gather intelligence about harbors, currents, and the island’s approach. Volusenus’ reconnaissance, though limited to observations from his ship, provided essential data for the campaign.

In addition to these formal sources, Caesar sometimes benefited from rumors spreading across Gaul, as he notes they had a tendency to rapidly share important events.

Julius Caesar crossing the Rubicon river. Credits: Gustave Boulanger, Public domain

Despite his methods, Caesar’s intelligence was sometimes incomplete. For instance, before his first British invasion, he relied on the limited findings from Volusenus’ brief mission and the traders' reports, which turned out to be insufficient for the campaign's full success. Nevertheless, Caesar's ability to gather and use intelligence was a significant factor in his military achievements. (The "Missing Dimension" of C. Julius Caesar, by Amiram Ezov)

“He was highly skilled in arms and horsemanship, and of incredible powers of endurance.

On the march he headed his army, sometimes on horseback, but oftener on foot, bareheaded both in the heat of the sun and in rain.

He covered great distances with incredible speed, making a hundred miles a day in a hired carriage and with little baggage, swimming the rivers which barred his path or crossing them on inflated skins, and very often arriving before the messengers sent to announce his coming.”

Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: