The Unknown Lucullus: Far more than just Lucullan Meals

Lucius Licinius Lucullus was a prominent Roman general, statesman, and politician, best known for his luxurious lifestyle and lavish feasts, which became almost legendary in Roman culture.

Lucullus had a distinguished military career, particularly known for his campaigns against King Mithridates VI of Pontus during the Third Mithridatic War, but he is more famously remembered for his opulent banquets and extravagant entertainments.

Lucullus’ Interesting Backstory

Lucius Licinius Lucullus (118–57/56 BC) was part of the plebeian Licinian family, which regained political prominence in the late third century BCE. His ancestors included influential figures, such as the curule aedile of 202 BCE, who helped elevate the family’s status. Lucullus inherited both wealth and status from his grandfather, who became consul in 151 BCE but was notorious for his brutal conduct in Spain, including massacres of civilians during his campaigns against the Celtiberi and Vaccaei.

Scholars in both ancient Rome and today generally agree that the name "Lucullus" is a diminutive form of "Lucius," which translates to "born at dawn." Lucullus' father, also named Lucius, benefited from his marriage into the powerful Caecilia Metella family, which strengthened his political influence. He became praetor in 104 BCE and led military efforts against a slave rebellion in southern Italy, followed by the Second Sicilian Slave War.

Although initially successful, his later inactivity in Sicily was criticized, with some suggesting either laziness or corruption. Overall, Lucullus’ family history is a mix of military service, political ambition, and controversy, which set the foundation for Lucullus’ own rise to power in Roman society.

Lucullus faced difficulties when C. Servilius was sent to replace him in 102 BCE, leading to a bitter reaction where Lucullus disbanded his troops and destroyed his camp to complicate things for his successor. This move backfired, as Servilius filed a complaint, and his cousin, Servilius the Augur, pursued legal action against Lucullus, accusing him of extortion.

Despite seeking support from his powerful in-laws, including Metellus Numidicus, Lucullus found no help. Metellus, possibly offended by Lucullus' behavior or seeking to avoid involvement due to family connections, refused to intervene. Lucullus was ultimately convicted and exiled, sparking a feud between the Luculli and the Servilii families.

“In the case of Lucullus, his grandfather was a man of consular rank, and his uncle on his mother's side was Metellus, surnamed Numidicus. But as for his parents, his father was convicted of peculation, and his mother, Caecilia, had the bad name of a dissolute woman.

Lucullus himself, while he was still a mere youth, before he had entered public life or stood for any office, made it his first business to impeach his father's accuser, Servilius the Augur, whom he found wronging the commonwealth.

The Romans thought this a brilliant stroke, and the case was in everybody's mouth, like a great deed of prowess. Indeed, they thought the business of impeachment, on general principles and without special provocation, no ignoble thing, but were very desirous to see their young men fastening themselves on malefactors like high-bred whelps on wild beasts.

However, the case stirred up great animosity, so that sundry persons were actually wounded and slain, and Servilius was acquitted.

Lucullus was trained to speak fluently both Latin and Greek, so that Sulla, in writing his own memoirs, dedicated them to him, as a man who would set in order and duly arrange the history of the times better than himself.

For the style of Lucullus was not only businesslike and ready; the same was true of many another man's in the Forum. There,

"Like smitten tunny, through the billowy sea it dashed,"

although outside the Forum it was

"Withered, inelegant, and dead."

But Lucullus, from his youth up, was devoted to the genial and so‑called "liberal" culture then in vogue, wherein the Beautiful was sought.

And when he came to be well on in years, he suffered his mind to find complete leisure and repose, as it were after many struggles, in philosophy, encouraging the contemplative side of his nature, and giving timely halt and check, after his difference with Pompey, to the play of his ambition.

Now, as to his love of literature, this also is reported, in addition to what has already been said: when he was a young man, proceeding from jest to earnest in a conversation with Hortensius, the orator, and Sisenna, the historian, he agreed, on their suggestion of a poem and a history, both in Greek and Latin, that he would treat the Marsic war in whichever of these forms the lot should prescribe.

And it would seem that the lot prescribed a Greek history, for there is extant a Greek history of the Marsic war.”

Plutarch, The Parallel Lives, The Life of Lucullus

This feud paused during Metellus Numidicus' own exile but resumed when Lucullus and his brother Marcus, skilled in oratory, brought legal charges against Servilius the Augur. Although the brothers' performance in court was admired, they lost the case. Legal battles of this sort were common among Roman elites, seen as a legitimate form of retaliation and revenge, which was often passed down through generations. The brothers’ actions were viewed within Roman norms as honorable, though unusual, given the timing of their prosecution against a sitting quaestor.

The feud between the Luculli and Servilii families, although brief, was considered one of the most intense in Roman history. Lucullus had a second conflict with Servilius the Augur, who opposed Sulla during his march on Rome in 88 BCE, while Lucullus remained loyal to Sulla.

Although some believed Servilius supported Marius, it’s possible that he simply opposed Sulla’s actions without backing Marius. Despite the personal rivalry, P. Servilius Vatia Isauricus joined Sulla, demonstrating that political priorities often overruled family disputes. By 83 BCE, both families reconciled, as national interests took precedence.

Financially, Lucullus and his brother Marcus were unaffected by their father’s exile, as their grandfather had secured the family fortune. Marcus was adopted by M. Terentius Varro but retained his original name. The brothers stayed close, likely due to their shared experiences after their father’s departure. They maintained influence in southern Italy and Sicily, where their father had connections, and Lucullus fostered relationships with notable figures like the poet Archias and Sicilian leader Eupolemus. (Lucullus, A Life, by Arthur Peter Keaveney)

Lucullus‘ Rise and Achievements

Lucullus was deeply connected to the literary and philosophical circles of his time, maintaining friendships with figures such as Cicero and likely Lucretius. Although today his name is often associated with luxury and excess, symbolized by the term "Lucullan," his life reflects much more complexity, particularly in his engagement with Roman Epicureanism—a philosophy that, like Lucullus himself, has been misunderstood and mischaracterized.

His life highlights the delicate balance between his political and military responsibilities and his intellectual pursuits in poetry and philosophy.

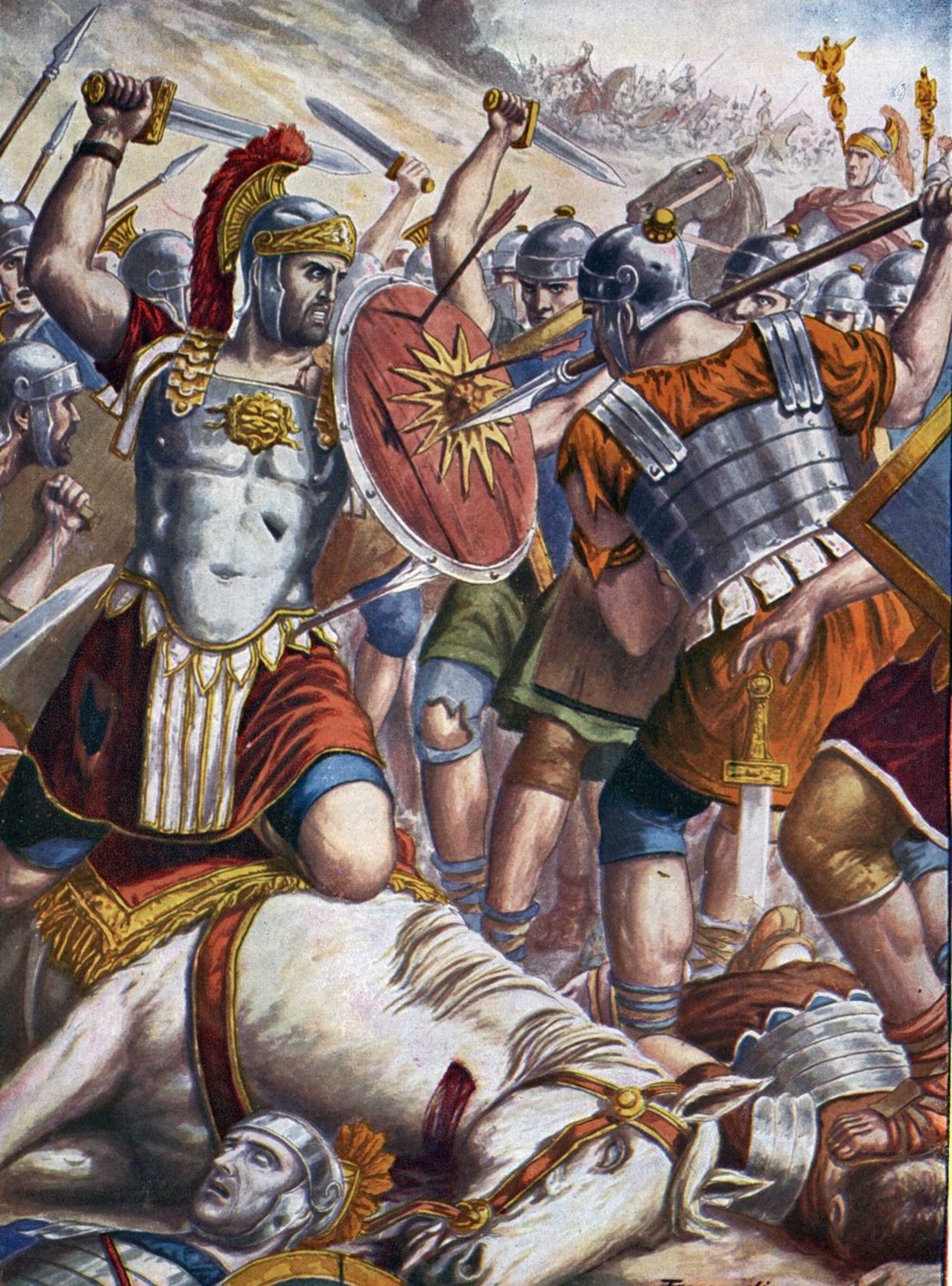

Roman general Lucullus conquered Tigrane II and the Pontic and Armenian armies and seized Tigranocerte. Illustration by Tancredi Scarpelli

Lucullus is portrayed not just as a military leader but also as a man of profound convictions, especially in his loyalty to family and friends, demonstrated through his adherence to pietas (duty). However, his struggle to balance his passion for learning with the harsh realities of Roman power and politics suggests that he was, in some ways, ill-suited for the demands of his era. His failure, in a sense, reflects the limitations of the Roman Republic and its ruling class.

In addition to his political career, Lucullus was well-versed in military tactics, excelling both in naval and land warfare, which was particularly important during a period when Rome faced increasing piracy in the Mediterranean. His military campaigns provide an education in various tactical operations, including infantry, cavalry, and siege warfare.

Yet, Lucullus' life also underscores the tension between his admiration for Greek culture—especially the romantic legends of Achilles and Alexander the Great—and the more pragmatic and constrained world of the Roman Republic. This tension offers insight into the enigma of Lucullus as a man torn between conflicting ideals.

For many students and scholars of Roman military history, Lucullus is often perceived as a somewhat obscure republican figure. However, Lucullus was, in many ways, a quintessential hero of the Roman Republic. He was a highly skilled military general with a remarkable record of victories, particularly against Rome’s Eastern enemies.

Beyond his military accomplishments, Lucullus was also a passionate patron of the arts and literature, which sometimes became ammunition for his critics. His extensive travels and experiences positioned him as a symbol of the Roman Republic’s spirit of exploration and colonization.

Though Lucullus had his share of flaws, no serious scholar or contemporary has ever doubted the importance of his military successes. He was often compared to Alexander the Great, and while Pompey ultimately gained that title, Lucullus helped pave the way for him. Among the major political and military figures of the late Republic, Lucullus also stood out for his intellectual interests, which make him a "Renaissance man" by today’s standards—a figure with wide-ranging talents and interests.

Despite his accomplishments, Lucullus' fame eventually faded, overshadowed by the rise of Pompey and Caesar. His later years are often associated with rumors of indulgence and possible mental decline, leading some to speculate about conditions like Alzheimer's or accidental poisoning. These final years offer an interesting chapter in his story, which deserves more scrutiny to separate fact from rumor.

Lucullus' life offers valuable insights into the military and political challenges of his time. Plutarch provides the most comprehensive surviving account of Lucullus, making it the primary source for understanding his military exploits and other accomplishments. Lucullus lived during a period of immense upheaval, witnessing events that some would consider the end of the Roman Republic.

His life embodies the experiences of a republican Roman, with his personal history tightly interwoven with the Republic he served both in times of peace and war. While Plutarch's account is critical, like all ancient sources, it must be examined for potential biases and inaccuracies. Without it, however, our understanding of Lucullus would be significantly diminished.

Plutarch's portrayal divides Lucullus' life into two distinct phases: one marked by industriousness and careful planning, and the other by the luxurious decadence that gave rise to the term lucullan. This binary characterization is not without controversy, as Plutarch's critique of Lucullus' later years may not fully reflect the positive aspects of his earlier life. Despite these complexities, Lucullus' life remains a fascinating and instructive example of the military and political realities of his era.

Lucullus’ Greek Influence and Tale of Vengeance

Lucullus' early life was deeply influenced by Greek language, literature, and a poet who likely played a significant role in shaping his intellectual development. Energetic and bright, young Lucullus was immersed in epic poetry, history, tragedy, and lyric, alongside Greek philosophical writings.

His home may have served as a small hub for Hellenic culture within the Roman Republic.

Head of goddess Nemesis in the Ancient Agora Museum. Credits: George E. Koronaios, CC BY-SA 4.0

Lucullus and his brother, Marcus, were exposed to Greek literature's rich tradition, from Homer’s martial epics to the tragedies and histories of wars between the Greeks and Persians. These works offered valuable lessons to a young Roman aristocrat, lessons that Lucullus would later apply in his own life and career.

Rhetoric and oratory were key components of the Roman education system for young boys. In their quest to avenge their father’s dishonor, Plutarch likens Lucullus and his younger brother Marcus to well-bred pups, noble hounds sent to track down and destroy the wild animals that had wronged their father. The exact timing of their legal action against Servilius is unclear, with accusations of embezzling funds as quaestor, though the specifics of the charges remain uncertain.

What is known, however, is that the court proceedings turned violent, leading to numerous injuries and even deaths amidst the chaos. Plutarch’s metaphor of the brothers as fierce young dogs attacking wild beasts may hint at the physical skirmishes that disrupted the trial. Yet, if Plutarch is reliable—and there seems no reason to doubt him in this case—Lucius and Marcus made a notably positive impression on the audience.

Their entry into Roman public life was not tarnished by the violence. Lucius, in particular, made the most of his education; skill in public speaking was vital for political success and held significant value in the military when commanding soldiers—a skill Lucullus would later struggle with, though not due to lack of eloquence. At this stage, Lucullus was recognized as a gifted orator, well-equipped for a public career.

Despite Servilius’ acquittal, the Lucullus brothers earned admiration for their rhetorical prowess and did not face any setbacks from the loss. Plutarch quickly shifts his narrative to Lucullus' literary and historical education. Lucullus became proficient in both Greek and Latin, with remarkable speaking and writing skills in politics and government.

He was even credited with writing a history of the Social War in Greek, an impressive achievement for a native Latin speaker. The topic itself was difficult, and scholars today still struggle with the lack of reliable ancient sources for this brutal conflict. The Social War, with its grim subject matter, unsurprisingly failed to attract the attention of Rome’s great historians.

In a letter from Cicero to Atticus, there is an intriguing detail about Lucullus' literary and historical ambitions. Cicero mentions that Lucullus intentionally made errors in Greek in his historical writings so that readers could easily identify the work as being authored by a Roman. It is unclear which historical works Cicero was referring to, though it might relate to Lucullus' account of the Social War, as mentioned by Plutarch.

Plutarch also notes that Lucius Cornelius Sulla dedicated his memoirs to Lucullus, acknowledging that Lucullus had greater skill in composing and organizing historical works. The context of Cicero's remark is a passage where he mentions sending Atticus a draft of his Greek work on his consulship. Unlike Lucullus' intentional errors, Cicero adds that any mistakes in his own Greek were purely accidental. He also promises to send a Latin version, along with a poem. (Lucullus, The Life and Campaigns of a Roman Conqueror, by Lee Fratantuono)

Lucullus’ Immense Wealth

Like us, the Romans chose leisure activities based on their preferences, personalities, and financial means. Cicero, with a hint of snobbery, reminded his audience that he spent his free time on literature, whereas others wasted it on excessive eating and gambling. Similarly, Sallust boasted that he pursued history writing instead of spending his time on farming or hunting.

Lucullus, on the other hand, chose to build—though not grand public buildings, but lavish and extravagant private palaces.

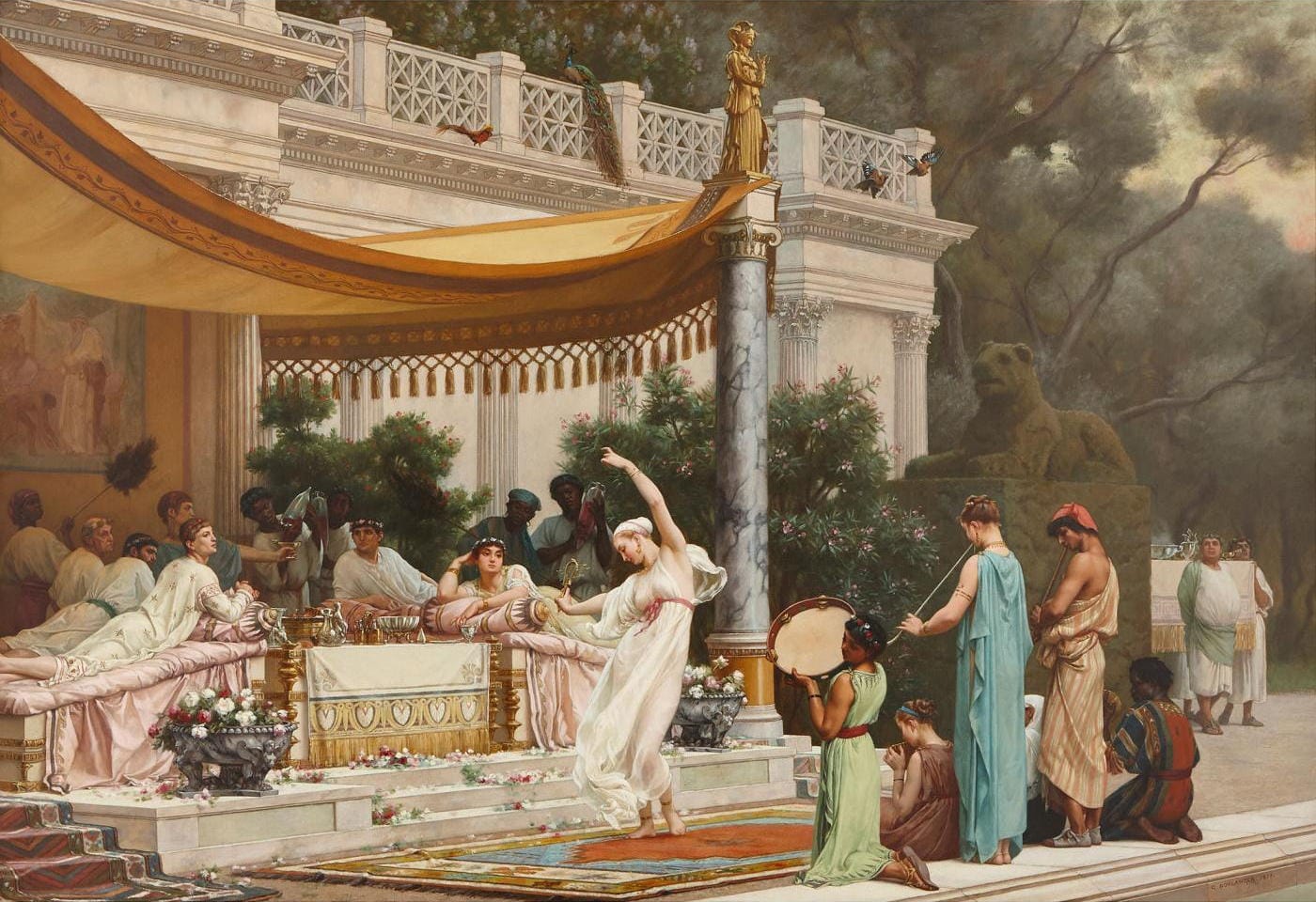

A summer repast at the house of Lucullus (painting by Gustave Boulanger, 1877). Public domain

Financially, he faced no obstacles. We've already tracked the growth of Lucullus' wealth: he inherited a decent estate from his father, gained more during the First Mithridatic War, and later amassed significant booty from his own campaigns. Although the exact amount of his fortune is unclear, it’s evident from what follows that Lucullus had become extremely wealthy.

In the pre-industrial world, there were limited options for investing surplus capital. Lucullus appears to have lent some of his wealth at interest, possibly in collaboration with Q. Caecilius. Lucullus counted this uncle of Atticus among his friends and even helped advance Caecilius’ fortunes, leading to expectations that Lucullus would inherit from him.

However, Atticus was ultimately chosen as Caecilius' heir. According to one account, the Roman people, outraged, dragged Caecilius' body through the streets. Not long after this incident in 56 BC, the plebs showed their affection for Lucullus in another demonstration, though the authenticity of this particular report is questionable.

Lucullus primarily spent his wealth on acquiring and enhancing luxurious properties. Even before his campaign against Mithridates, he had already begun indulging this passion. It’s worth recalling that in 67 BC, when Gabinius sought to discredit Lucullus and portray him as unfit for command, he circulated images of the villa Lucullus was constructing in the fashionable town of Tusculum.

However, the villa likely didn’t achieve its final grandeur until Lucullus returned and devoted his full attention to it. Some parts of the villa may have been constructed from the black marble quarried on Melos, which was later named "Lucullan" after him.

This material was used to build an impressive complex of vast proportions—so large that it could have attracted the censor’s disapproval. The practical-minded Romans believed that the size of a farm's buildings should be proportional to the acreage, with no more space than needed to house workers and equipment. Otherwise, the censor could intervene. Lucullus risked the common rebuke that he had "more to sweep than to plough."

Lucullus’ Legendary Banquets

One notable feature of the house was a unique dining room that also served as an aviary. Guests could dine while observing birds fluttering behind the windows, adding to the refined atmosphere. However, the pleasure was somewhat marred by the smell from the bird enclosure. In fact, it is likely that Lucullus' famous banquets have played a significant role in his enduring reputation. Even those unfamiliar with Lucullus himself recognize the phrase "Lucullan banquets."

An ancient writer once described Lucullus as dining like a satrap, likely prompted by his use of purple fabric to adorn his dining couches. Purple cloth seemed plentiful in Lucullus’ household, as demonstrated when a praetor requested a hundred purple cloaks for a festival, and Lucullus had so many that he could easily provide twice that amount.

Additionally, his guests drank from cups encrusted with precious stones and were entertained with choruses and recitations during their meals. Accounts of his dinners mainly focus on the main course, where a wide variety of meats and highly elaborate pastries were served. Although nothing is mentioned about the first course or dessert, it is likely that cherries, which Lucullus had introduced to Italy from Pontus, featured prominently in the dessert.

Unfortunately, we have few specific details about Lucullus' dinners. There is no clear record of what was served, and we don’t even know if the guests enjoyed themselves.

Instead, we are left with one ambiguous anecdote that could suggest Lucullus lacked self-control and several stories emphasizing his extravagance. According to the elder Pliny, Lucullus attended public events with a slave whose duty was to ensure that Lucullus didn’t overeat. Pliny saw this as evidence of Lucullus’ lack of self-discipline, though a more charitable view might be that Lucullus was simply mindful of the challenges of his position and took precautions to manage them.

Another story tells of a group of Greeks who stayed with Lucullus and worried they might be consuming too much of his resources, only to be reassured that while Lucullus was spending money on them, most of it was on himself. On another occasion, Lucullus dined alone and was served a modest meal. When the steward explained that a simple dinner was prepared because no guests were expected, Lucullus famously replied that "Lucullus dines with Lucullus," indicating that even when dining alone, he expected a lavish meal.

This story reminded Plutarch of another. Cicero and Pompey, doubting the tales of Lucullus’ extravagance, approached him in the Forum and asked to join him for dinner that very day. They wanted to see the type of meal Lucullus would have eaten alone. Though he tried to dissuade them, Lucullus finally instructed a slave to prepare the Apollo Room. Each dining room in Lucullus’ estate had its own budget, and a meal in the Apollo Room cost 200,000 sesterces.

Athenaeus actually dates the beginning of extravagance in dining with Lucullus’ banquets. The image of Lucullus’ banquets has persisted through history as a symbol of excess and refinement, emphasizing the distinctive Roman penchant for grand feasts. Extravagance in Roman dining was not universal, however.

Bulimia during Lucullan Meals

Those types of banquets were typically limited to the wealthiest elite, as exemplified by Lucullus. The upper class indulged in extreme eating habits, including the notorious practice of purging, or vomiting, after meals. This behavior was less about nutrition and more about social status and the ability to indulge in excess without consequence. Only the wealthiest Romans could afford to engage in such practices, demonstrating their dominance over both their resources and their bodies. This act of bulimia was seen as a mark of luxury, rather than a disorder, in Roman high society.

Lucullus’ feasts were so influential that even centuries later, historical figures such as Lord Byron drew comparisons between the banquets of his era and those of Lucullus. Byron, who was likely struggling with his own eating disorders, expressed a fascination with excess in consumption, mirroring the lavishness of Roman feasts.

His commentary on food reflected a critique of indulgence in modern times, where grand banquets continued to serve as a social statement, much like those in Lucullus’ time. The comparison reveals how deeply ingrained the image of Lucullan banquets had become in Western culture.

Byron’s ambivalence toward food is further highlighted by his personal struggles with bulimia, a condition characterized by cycles of binging and purging, much like the extreme dining habits of ancient Rome. His reflections on feasting in his works, such as Don Juan, show a critical awareness of the social and cultural meanings behind overconsumption. Byron’s personal relationship with food, combined with his literary critique, offers a poignant connection between the indulgence of Lucullus and the excesses of the modern era. (Man is a Carnivorous Production: Byron and the Anthropology of Food, by Christine Kenyon Jones)

Lucullus Fading into History

Yet, not all of Lucullus' villa was dedicated to luxury; part of it was a renowned library, with a strong collection of philosophical works, many of which came from his eastern conquests. Lucullus welcomed visitors to his library, and even after his death, the tradition continued.

For example, Cicero once visited during Lucullus Jr.’s minority to borrow books, having come from his nearby villa. In Lucullus’ lifetime, he especially welcomed Greek scholars, who were given access to all his rooms. Lucullus often mingled and conversed with them, and many Greek visitors, in Rome on official business, sought his advice and help in presenting their cases to Roman authorities.

It can be said that Lucullus, a once towering figure of Roman history, a man of great achievements, only has few tangible artifacts from his life remaining.

A possible representation of inside Lucullus’ illustrious Roman Villa. Illustration: Midjourney

His legacy, once rich with contributions to Rome’s military expansion and intellectual life, has gradually faded, leaving behind only scattered references in ancient texts and the memory of his extraordinary wealth. The villas he built, the lands he conquered, and the cultural circles he influenced have largely dissolved into the passage of time; what remains most vividly in the public imagination, however, is not his political or military prowess, but his association with opulence and indulgence, that now defines his name.

This emphasis on Lucullus’ extravagance underscores the impermanence of wealth and material achievement. While his grand feasts and luxurious lifestyle continue to capture the curiosity of historians and cultural commentators, the substance of his influence—his contributions to Rome’s cultural and political fabric—has been overshadowed by tales of decadence.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: