The Tragic Philosopher: Seneca the Younger’s Journey Through Stoicism and Politics

Seneca the Younger, a towering figure of the Roman intellectual world, lived a life filled with paradoxes.

As a Stoic philosopher, Seneca advocated for simplicity, virtue, and self-discipline, yet he navigated the treacherous waters of Roman imperial politics, serving as an advisor to the notoriously volatile Emperor Nero.

Born in Corduba (modern-day Córdoba, Spain) around 4 BCE, Seneca became one of the most influential writers and thinkers of his time. His works, ranging from philosophical treatises to tragedies, offer profound insights into ethics, resilience, and the human condition. Despite his teachings on tranquility and detachment, Seneca’s life was marred by political intrigue, accusations of hypocrisy, and a dramatic fall from grace that culminated in his forced suicide in 65 CE.

Seneca’s Paradox: A Philosopher’s Struggle Between Life, Death, and Stoic Ideals

Lucius Annaeus Seneca's death in 65 CE was as dramatic and paradoxical as his life. Accused of conspiring against Emperor Nero, Seneca was compelled to take his own life. According to Tacitus, Seneca, then around 65 or 70 years old, faced his end in the company of his wife and friends.

Despite his Stoic resolve, his death was prolonged and arduous. After slitting his veins failed and a dose of hemlock proved ineffective, he finally succumbed to suffocation in a hot steam bath, a poignant irony given his lifelong struggles with respiratory issues like asthma.

Seneca modeled his final moments on the death of Socrates, as depicted in Plato's Phaedo, where the philosopher dies serenely among his companions after a discussion on the soul. Yet, Seneca’s death was anything but serene.

Tacitus notes that he chose not to record Seneca’s final words, hinting that Seneca’s public works and self-fashioning had already shaped his narrative for posterity. Unlike Socrates, whose calm death aligned perfectly with his philosophical ideals, Seneca's was a series of failed attempts and improvised solutions, filled with tension and uncertainty—a marked departure from the Socratic ideal.

This juxtaposition highlights the contradictions in Seneca’s life as a philosopher entangled in the murky politics of Nero’s court. While he famously wrote, “The whole of life is a preparation for death” (On the Shortness of Life), Seneca’s death reflected his uneasy compromise between philosophical ideals and political survival. Tacitus captures this tension, showing Seneca as a man striving for Stoic tranquility even in his final moments.

Seneca's philosophical teachings, rooted in Stoicism, emphasized freedom, resilience, and rising above fortune. He asserted in On Providence, “I have made nothing easier than dying,” and encouraged overcoming challenges with willpower, writing, “It is not because things are difficult that we don’t dare to do them; our lack of daring makes them difficult” (Epistle). Yet, Seneca himself admitted to being far from the Stoic ideal.

He presented himself as a proficiens—a philosopher still on the path, not one who had achieved enlightenment.

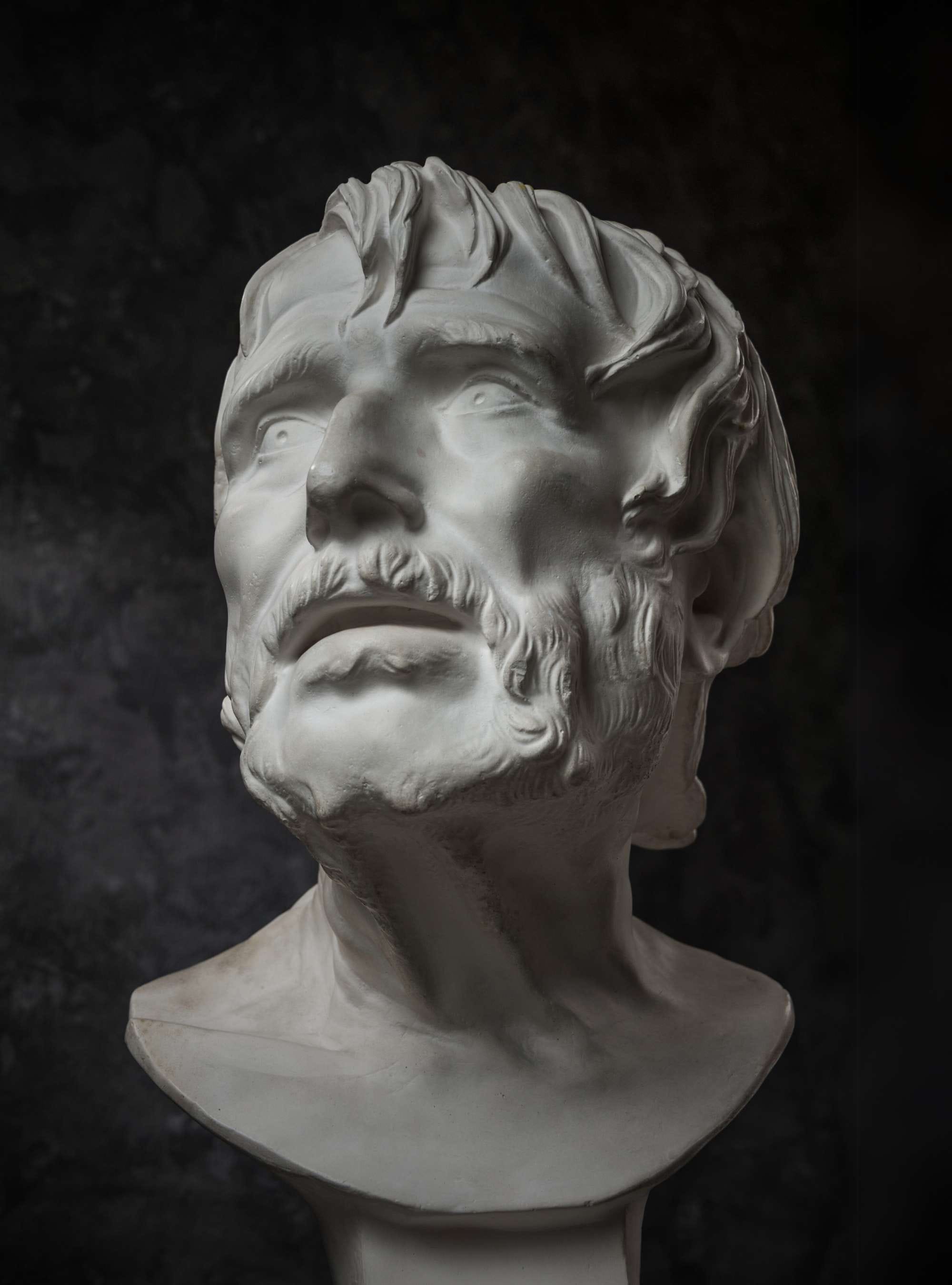

Bust of Roman philosopher Seneca. Credits: Calidius, CC BY-SA 3.0

His life was marked by struggles with his own principles. Rising from provincial obscurity to become one of the most powerful figures in Rome, Seneca amassed great wealth and influence but felt increasingly trapped and alienated. He eventually attempted to retire, returning wealth to Nero and withdrawing from court in 64 CE, yet this did not save him from condemnation.

Tacitus’ depiction of Seneca’s death emphasizes the philosopher’s humanity—his failure to meet the Stoic ideal underscores the complexities of living a philosophical life amidst the pressures of imperial power. Seneca’s end, like his life, is a compelling reflection on the tension between virtue and compromise, ideals and reality, and the profound difficulty of reconciling philosophy with the exigencies of politics.

Philosophy, Power, and the Struggle for Authenticity

Seneca the Younger’s writings offer an intimate glimpse into his philosophical musings and reflections on daily life. Yet, his works are far from autobiographical.

Unlike Cicero’s personal letters to Atticus, Seneca’s writings—whether on exile, wealth, or morality—are carefully crafted public performances. His accounts of exile, for instance, are more literary recreations inspired by Ovid than factual narratives. Similarly, his works reveal little about his domestic life or his fraught relationship with Emperor Nero, leaving readers to sift through his writings for fragmented insights into his lived experiences.

Seneca wrestled with a deeply Stoic ideal: the constancy (constantia) of the wise man, who remains unshaken by life’s vicissitudes. He famously declared, “What is wisdom? Always wanting the same things and refusing the same things.” Yet, his life was marked by contradictions. A philosopher devoted to simplicity, Seneca simultaneously amassed immense wealth.

A counselor to an increasingly despotic Nero, he preached tranquility while navigating the treacherous waters of imperial politics.

Gypsum copy of Seneca’s head, now marked as Pseudo Seneca, most likely belonging to Hesiod. Credits: bashta from Getty Images, by Canva

This tension reflects the broader struggle of elite Romans during the Principate, a time when old republican values clashed with the realities of autocratic rule. Unlike Cicero, who clung to the republican ideals of oratory and political engagement, Seneca viewed philosophy as an internal refuge. His Stoicism was not a means to transform government but a tool for individual resilience.

While Cicero’s political activism aimed to restore the Republic, Seneca sought personal autonomy amidst the instability of Nero’s court. Seneca’s ability to articulate the emptiness of wealth and the futility of ambition was not theoretical; it stemmed from lived experience.

He understood firsthand the perils of luxury, observing that “Wealth doesn’t make a king” (Thyestes) and cautioning against the volatility of fortune: “A man that dawn sees proud, dusk sees laid low.” This pragmatic perspective distinguished Seneca as a philosopher of action, navigating a world where survival often required compromise.

Unlike Cicero, whose eclectic philosophical interests reflected a broader exploration of various schools, Seneca was deeply committed to Stoicism. Where Cicero criticized the Stoic pursuit of apatheia (freedom from passion) as unrealistic and detached, Seneca saw it as a necessary armor for life at the heart of Roman political power. His writings do not always align seamlessly with his life, but they capture a profound effort to reconcile ideals with reality.

Seneca’s philosophy was not merely a guide for self-improvement but also a commentary on the fractured nature of his world. He grappled with the contradictions of his position—a man striving for inner peace while deeply embedded in the turbulent politics of the Julio-Claudian court. His work resonates today as an exploration of what it means to live authentically amidst competing pressures, embodying the struggle to find coherence in a world fraught with complexity. (The greatest empire, A life of Seneca, by Emily Wilson)

The Challenge of Unveiling the Man Behind the Moralist

The complexities of Lucius Annaeus Seneca’s life and works present a fascinating challenge for scholars. Tacitus provides the primary lens through which Seneca the statesman is known, yet Seneca himself, despite his extensive writings, reveals little about his political career or personal life.

His philosophical works, including De Clementia and Apocolocyntosis, touch on themes relevant to his role as amicus principis (friend of the emperor), but most of his writings focus on moral philosophy, leaving significant gaps in our understanding of the man behind the ideas.

Seneca’s prose, while addressed to contemporaries, rarely delves into the events or individuals of his time. His letters and dialogues are more introspective, emphasizing inner life and moral guidance over autobiographical detail. Even in his letters to Lucilius, which are richer in personal anecdotes, Seneca prioritizes philosophical reflection over self-revelation. He positions himself as a moral exemplar, offering lessons rather than an intimate portrait of his life.

This reticence stems from multiple factors. Seneca’s philosophy centered on the cultivation of the inner self, making personal and external details secondary. His role as a moral teacher further distanced him from the political and personal realities that might have complicated his public persona. Additionally, his works were crafted for a broader audience, reflecting his intention to educate and persuade rather than to document his life.

Despite this, Seneca’s writings indirectly illuminate his experiences and values. His focus on free speech, anger in leadership, and the responsibilities of power suggest a Stoic framework applied not only to private life but also to his public dealings. His discussions of Augustus, Tiberius, and Nero, alongside his use of Roman exempla, reveal his views on the interplay between philosophy and governance.

Seneca’s decision to write philosophy in Latin, a medium traditionally reserved for Greek, underscores his ambition to elevate moral philosophy within Roman culture. His works reflect a tension between his literary and philosophical ambitions and his lived reality as a statesman navigating the Julio-Claudian court.

Ultimately, while Seneca sought to align his philosophy with his life, his writings often reveal the contradictions and compromises of his position. His philosophy offered an aspirational ideal, even as he grappled with the complexities of his role as a political advisor and public intellectual. Understanding Seneca requires navigating the delicate balance between the man, his works, and the turbulent world in which he lived. (Seneca, A philosopher in politics, by Miriam T. Griffin)

Seneca and Agrippina: The Complexities of Loyalty, Politics, and Influence

Seneca remains a figure of enduring intrigue, with his life and character stirring debate among scholars. This complexity arises not only from the sparse and contradictory ancient sources, but also from the gaps in documentation, particularly regarding his earlier years and his role in the political intricacies of the Julio-Claudian court.

Tacitus provides a crucial, though incomplete, narrative of Seneca’s life, particularly regarding his exile under Emperor Claudius and his subsequent return to prominence at the behest of Agrippina. Tacitus suggests that Seneca's loyalty to Agrippina stemmed from gratitude for a beneficium she extended to him—a favor possibly dating back to 39 CE during Caligula’s reign.

Agrippina’s influence, coupled with Seneca’s literary and political skills, positioned him as a valuable ally in her bid for domination when she married Claudius in 49 CE. The historical record hints at Seneca’s precarious position in Caligula’s court. A passage in Dio Cassius describes a court lady intervening to save Seneca from Caligula’s wrath, a scenario consistent with Agrippina’s known influence during this period.

While conjectural, the hypothesis that Agrippina aided Seneca aligns with Tacitus’s later depiction of their alliance and Seneca’s gratitude.

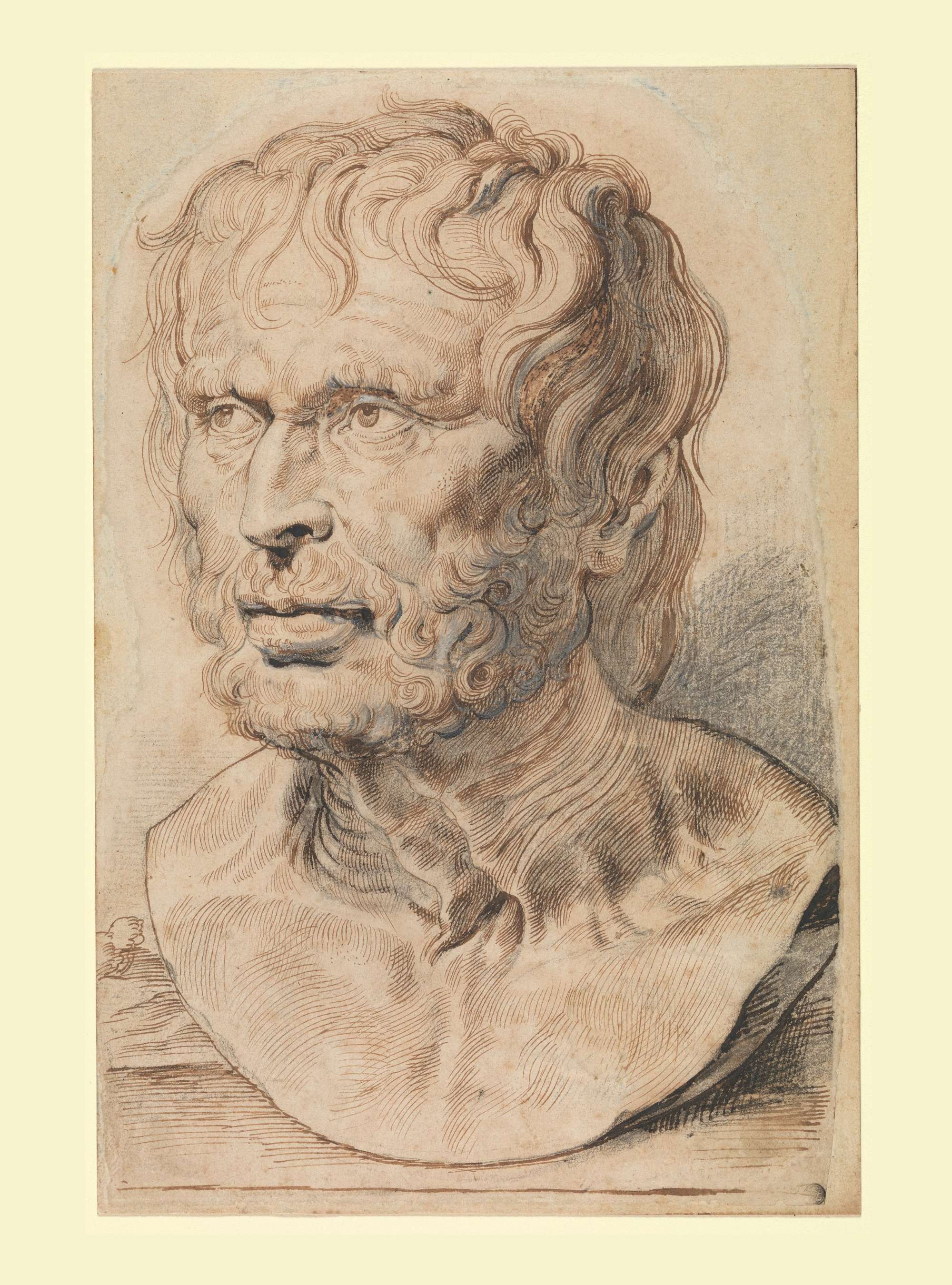

A sketch of a bust of Pseudo-Seneca by Peter Paul Rubens. Credits: The MET, Public domain

Seneca’s trial and exile in 41 CE, ostensibly for immoral relations with Julia Livilla, Agrippina’s sister, further suggest his entanglement in imperial court intrigues. Despite the charges, Seneca managed to survive politically tumultuous years, possibly due to Agrippina’s support. The episode exemplifies his ability to navigate the dangerous currents of Roman politics while maintaining his philosophical pursuits.

The interplay between Seneca’s philosophical ideals and his political actions continues to fascinate scholars. His writings, while rich in moral philosophy, offer little direct insight into his political maneuvers or personal relationships. Nevertheless, his works reflect a Stoic framework applied to governance, emphasizing self-control, generosity, and the responsibilities of power.

Ultimately, Seneca’s life embodies the contradictions of a philosopher-statesman: a man deeply enmeshed in the treacherous politics of the Roman court while advocating for Stoic detachment and virtue. The possible role of Agrippina in his survival and ascent underscores the complex web of loyalty, ambition, and gratitude that defined his career. This interplay between philosophy and politics, ideals and reality, continues to define the enduring enigma of Seneca. (Seneca the Younger under Caligula, by G. W. Clarke, Societe d’Etudes Latines de Bruxelles)

The Seneca Effect: The Rise and Rapid Fall of Rome and its Philosophy

Seneca epitomizes the paradox of rapid decline after great success—a phenomenon aptly termed the "Seneca Effect." As already mentioned, rising to wealth and influence, he served as tutor and adviser to Emperor Nero, but his fortunes quickly unraveled. Accused of conspiracy against Nero, Seneca was forced to commit suicide, embodying his own aphorism that “ruin is rapid.”

This concept parallels the trajectory of the Roman Empire itself. Despite its grandeur, Rome began to show signs of decline as early as 9 CE, following the catastrophic defeat in the Teutoburg Forest. Augustus, ever the propagandist, turned the loss into a narrative of resilience, but the cracks in the Empire's foundation grew more evident over time. By the 5th century CE, Rome was a shadow of its former self, marked by economic decline, reduced population, abandoned cities, and recurring invasions.

Authors like Rutilius Claudius Namatianus and Paulinus of Pella vividly chronicled the collapse, describing derelict infrastructure and the dissolution of law and order. The sackings of Rome in 410 and 455 CE by the Goths and Vandals, respectively, signaled the Empire’s final stages. While the Eastern Roman Empire endured longer, it could not revive the West.

The "Seneca Effect" serves as a poignant metaphor for Rome’s fall: a millennium of growth undone in a few centuries. To understand the mechanisms of collapse, however, one must first grasp the forces that sustain such empires.

Seneca’s later writings, including the Moral Letters to Lucilius and Investigations into Nature (Naturales Quaestiones), showcase his enduring engagement with Stoic philosophy. These works reflect his struggle to reconcile the ideals of Stoicism with the political realities of imperial Rome. His career and writings provide a vivid lens through which to view the complexities of power, morality, and human frailty in the Roman Empire.

From Andalusian Roots to Roman Prestige

Lucius Annaeus Seneca’s remarkable ascent from a provincial Andalusian family to one of Rome’s highest honors—membership in the Senate and the rank of consul—epitomizes the possibilities offered by Roman society to talented and ambitious individuals. The son of a wealthy equestrian family, Seneca was part of a lineage steeped in Roman culture. His father, Seneca the Elder, was a historian and orator who moved to Rome, where his sons would receive an elite education.

The younger Seneca’s trajectory was shaped by the Roman system of clientela (patron-client relationships), which required not only wealth and connections but also the endorsement of powerful social figures. This system enabled Seneca and his brothers—Gallio, a senator and governor of Greece, and Mela, a high-ranking imperial official—to achieve illustrious careers. All three, however, met tragic ends, committing suicide in 65 CE amid Nero’s purges, along with their nephew, the poet Lucan.

Seneca the Elder initially underestimated his middle son, viewing him as a social climber and less gifted in the art of declamation, the prized skill of oratory. Yet Seneca the Younger’s true passion lay in philosophy, which he pursued under influential teachers in Rome. This philosophical inclination set him apart, aligning him with the Stoic tradition that emphasized moral rigor over rhetorical flourish.

Despite his father’s doubts, Seneca’s literary and philosophical works transcended the superficialities of oratory. His philosophical writings remain enduring contributions to Stoicism, and his life reflects the cultural and political dynamics of a Roman Empire that prized culture as a marker of status and identity. Seneca’s story is both a testament to the opportunities afforded by Roman civilization and a poignant example of the perils of political ambition in an imperial system rife with intrigue.

“When I used to listen to my teacher Attalos stigmatize the evil, the follies and the errors of our existence, I would take pity on humankind and conclude that my teacher was sublime and mightier than kings.

If he praised poverty, when I left the class I would want to be poor or to forbid myself gluttony and sensuality.

I still retain from this certain habits, never indulging in oysters or mushrooms or perfumes or steam baths. I still sleep on a hard mattress.

Likewise, enthusiastic about Pythagoras and reincarnation, I had become a vegetarian.

But just at that time, the police had been swept by a wave of suspicion against alien superstitions contrary to Roman mores.

My father wasn't afraid of the police, but he despised philosophy, so he dissuaded me from vegetarianism.

I have told you this story to show you how enthusiastically adolescence embraces virtue."

Seneca

From Philosophy to Politics and the Perils of Imperial Favor

Seneca’s life journey reflects a remarkable blend of philosophical rigor, political ambition, and the dangers of navigating imperial Rome’s treacherous court. Trained in Stoic philosophy by influential teachers like Attalos of Alexandria, Seneca embraced philosophy as a quasi-religion in his youth, dedicating himself to ethical transformation rather than abstract theory.

This early grounding in Stoicism would define his life and writings. Seneca’s political career began in his late 30s, with his rhetorical skills and sharp intellect quickly earning him fame in Rome. His connections to the imperial family, particularly through relationships with Emperor Caligula’s sisters, elevated his status but also drew him into the court’s intrigues.

Caligula’s assassination in 41 CE provided temporary relief from his despotism, but Seneca’s ties to the imperial women led Emperor Claudius to accuse him of adultery with Agrippina’s sister. The accusation resulted in his exile to Corsica, a bleak eight-year period where Seneca immersed himself in study, writing, and natural history.

Despite his isolation, Seneca remained loyal to monarchic governance, distancing himself from the Stoic senatorial opposition. His exile ended when Agrippina, now Claudius’s wife, secured his recall in 49 CE, entrusting him with her son Nero’s education. This relationship would define Seneca’s later years, as he rose to unparalleled influence during Nero’s early reign but faced a rapid downfall as the emperor’s erratic and violent tendencies emerged.

Seneca’s multifaceted personality—philosopher, rhetorician, courtier, and statesman—made him both celebrated and controversial. While his Stoic ideals shaped his writings and public image, his political actions were often seen as pragmatic and occasionally contradictory. Ultimately, his proximity to power came at a high cost, culminating in his forced suicide. His life exemplifies the tension between philosophical ideals and the realities of political ambition in imperial Rome. (Seneca the life of a stoic, by Paul Veyne)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: