The Plague of Justinian: When Death Came to Constantinople

When death arrived by sea, Constantinople fell silent. Streets filled with the dead, incense rose over empty markets, and even the emperor took to his bed. The first pandemic of recorded history began with prayer—and an empire waiting for an answer.

In the spring of 542 CE, the Roman Empire awoke to silence. Ships brought not only grain to Constantinople but death—an invisible passenger that crept from the ports of Egypt to the heart of the imperial capital. Within weeks, the streets that once echoed with trade and prayer lay still. Bodies filled the squares; dogs starved beside their masters; and the emperor himself fell ill behind the marble walls of his palace.

It was the beginning of what Procopius called “a plague beyond all measure,” a visitation that would empty cities, cripple armies, and mark the first pandemic of recorded history. Beneath the golden domes of Justinian’s empire, the ancient world met its most relentless enemy: the unseen breath of death.

The Coming of the Justinianic Plague

In 540 CE, Emperor Justinian ordered the destruction of the ancient temple of Isis at Philae, determined to extinguish the last remnants of pagan worship. Isis had once been revered as the goddess who taught humankind the arts of healing and renewal; her silencing seemed to mark the triumph of Christian empire over the old gods.

Yet within a year, Egypt was struck by a pestilence that mocked that victory—a plague so vast and indiscriminate that even the faithful began to wonder whether the divine had turned away altogether.

According to Procopius of Caesarea, the disease first appeared at Pelusium on Egypt’s eastern frontier. From there, it crept through Alexandria and the Delta, advancing along the Mediterranean coast into Palestine and Syria, before following the grain ships northward toward Constantinople. In his Wars, Procopius described the calamity with the precision of a witness and the anguish of a survivor:

“Men dropped suddenly as they walked,”

he wrote,

“and the streets were filled with corpses.”

At first the dead were buried in family tombs,

“but when all the tombs that had existed previously were filled, they dug up every place about the city, one after another, and laid the bodies there as they could.”

Soon even these makeshift graves proved too few.

“Those who were making these trenches, no longer able to keep up with the number of dying, mounted the towers of the fortifications in Sycae, tore off the roofs, and threw the bodies in there in complete disorder.”

The air was heavy with incense and the stench of death. Procopius wrote that:

“on some days ten thousand died,”

though no one could count with certainty. The markets stood empty, the law courts silent, and the sea itself seemed choked with the dead. Even Justinian fell ill, and for a time it was said that the empire itself lay fevered.

Further south, John of Ephesus, traveling from Alexandria through Palestine and Syria, saw the plague’s devastation unfold across the countryside.

“It was told of one city on the Egyptian border,”

he wrote,

“that it perished completely, with only seven men and one boy of ten years remaining.”

He spoke of villages erased, roads lined with bodies, and

“houses and waystations occupied only by the dead.”

Cattle roamed untended across deserted fields, and the harvest rotted where it stood. Evagrius Scholasticus, who as a child survived the plague, later recalled in his Ecclesiastical History how the disease returned in cycles,

“each fifteenth year laying low those whom the earlier visitation had spared.”

He described the symptoms that marked the afflicted:

“boils in the groin, fevers that burned like fire, and a darkness before the eyes.”

The pestilence, he wrote,

“spared neither age nor condition—rich and poor alike were laid in the same dust.”

By the spring of 542, the plague had reached the imperial capital. Constantinople, the most magnificent city of its age, became a place of silence. Funeral chants echoed through the streets, and barges loaded with corpses drifted out into the Bosporus.

The emperor’s agents dug vast trenches in the suburbs, and when the ground could hold no more, they hurled the bodies into towers and cisterns. The living avoided one another’s gaze, for none could tell who would fall next.

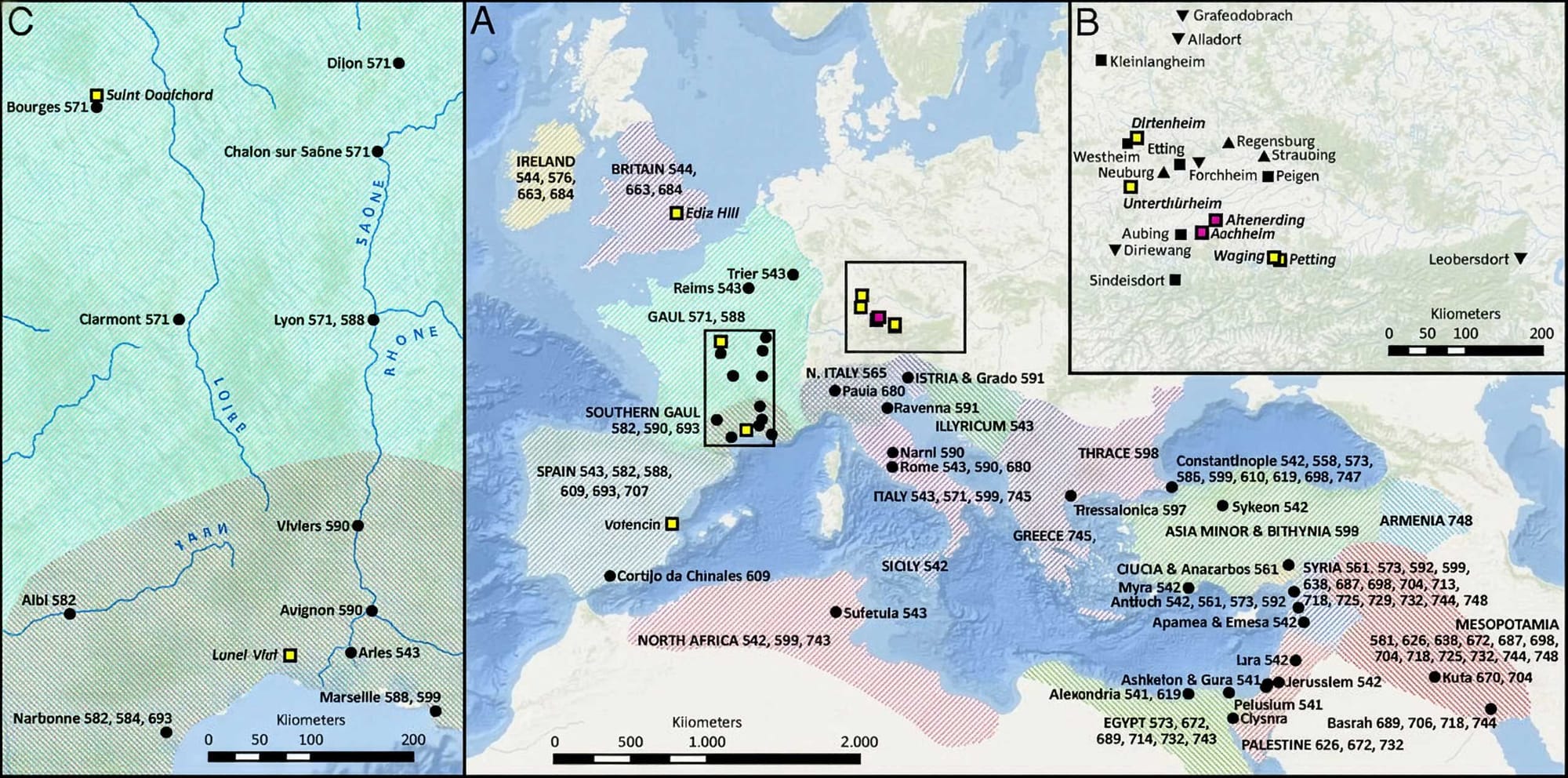

From Constantinople, the contagion spread outward—to Antioch, Illyricum, and Africa by year’s end; then to Spain, Italy, and Gaul; finally, to the distant British Isles. Merchant ships carried the unseen enemy from port to port. The Mediterranean, once the sea of trade and empire, had become a sea of death.

Its origin remained uncertain. Some said it arose from India; others, from the heart of Africa. Evagrius himself wrote that

“it was said to have begun in Ethiopia,”

echoing the old belief that pestilence came from the burning lands of the south. The geography of empire made such a path plausible: Byzantine merchants traded with Axum and the Red Sea ports, whose ships reached deep into the African interior. From there, the contagion may have traveled north with the grain fleets that fed the capital.

By the end of the 540s, the plague had circled the known world. Cities shrank, armies thinned, and harvests failed. In some regions, whole generations vanished. The survivors described the years that followed as an age of silence—fields untilled, temples and churches alike echoing with unanswered prayers.

For those who lived through it, the Justinianic Plague was not simply a natural disaster but a divine withdrawal. The gods, it seemed, had fallen silent. Procopius confessed that:

“the whole human race came near to being annihilated.”

John of Ephesus could only record what he saw and admit that “no tongue can describe” the horror. From Alexandria to Constantinople, incense burned night and day, the air thick with supplication. Yet the pestilence moved on, indifferent to prayer or empire.

In those years, faith itself became a test of endurance. The empire that had silenced the goddess of healing now faced an affliction no power could cure. The world of reason and revelation alike trembled before a darkness that neither science nor scripture could name. In the silence that followed, history itself seemed to hold its breath. (The Justinianic plague: origins and effects, by Peter Sarris)

What began as a calamity beyond imagining soon revealed a rhythm—a cycle that rose and fell like breath. The plague that first silenced Constantinople did not end with its retreat. It lingered in the air, returning in waves across the empire’s heartlands, reshaping the pulse of daily life and the machinery of survival.

How The First Pandemic Unfolded

The first great pandemic of recorded history unfolded not as a single catastrophe but as a cycle of devastation that returned again and again. Beginning in the mid-sixth century, the plague spread outward from the eastern Mediterranean, carried along sea lanes and river routes that linked the empire’s major ports.

Its advance was uneven—some towns were left desolate while others, separated by a few days’ march, escaped almost untouched. The rhythm of the outbreak depended on trade, season, and the fragile machinery of administration that kept grain, labor, and burial moving.

In Constantinople and other cities, life collapsed in recognizable stages. Markets closed, workshops fell silent, and bread grew scarce as carters and bakers sickened. Graveyards filled within days; when there was no room left, bodies were carried to porticoes, warehouses, and even the recesses of the sea walls.

Those who still stood hauled the dead through deserted streets by night, their paths lit only by torches and the dim glow from the harbor. Officials imposed price controls, requisitioned ships and carts, and pressed laborers into burial service, but where civic order faltered, silence and fear spread faster than the disease.

The symptoms appeared suddenly—fever that rose with violent heat, swellings in the groin or neck, dizziness, and a darkness before the eyes. Many collapsed within a day or two; a few survived, frail and trembling. The sick lay in doorways or by fountains where they had fallen; others died alone in their beds, unnoticed until the air itself turned heavy. Even the palace was not spared. The emperor was struck down but lived, an emblem of the empire’s own struggle between endurance and collapse.

The plague’s grip extended far beyond the body. With every wave, shortages deepened and confidence drained away. Labor grew scarce, wages shifted, and property changed hands through inheritance as families vanished. Cities that survived reopened slowly, only to be struck again. Across the empire, the plague’s mark was not total ruin but exhaustion—a long, uneven draining of life and order.

Through it all, the living kept to ritual: the washing of hands, the covering of faces, the measured step through streets lined with the dead. In their endurance lay the strange rhythm of this first pandemic—its horror balanced by the will to continue, its memory inscribed not only in chronicles but in the silence that followed each wave.

Empire Under Strain: The Burden of Survival

The plague did not merely empty streets; it thinned the sinews that held the empire together. Tax rolls fell into disorder as households vanished or split apart, and officials struggled to assess what no longer existed. Estates lacked hands to harvest and press; caravans arrived light or not at all; workshops opened late, then closed for good.

Where receipts once moved like clockwork from village to city to capital, gaps appeared—first weeks long, then months—until the rhythm of revenue turned irregular, and the state learned, grimly, to make do with less.

Shortages rearranged daily life. In some towns, bread cost more than soldiers’ pay; in others, grain lay unground for want of millers. The price of skilled work rose and fell unevenly—stonemasons suddenly scarce in one district, weavers gone in another—so that rebuilding a bathhouse or mending a bridge could take a year where it once took a season.

Families consolidated under single roofs; shops merged; fields were leased hastily to whoever could still lift a plough. The city called to the countryside for help, and the countryside, reeling, answered as it could.

Authority responded in fragments, then in patterns. Edicts tried to steady wages and keep vital trades at their benches. Requisitions moved grain along river and sea to the hungriest markets. In places where curiales, the city councillors, had once shouldered civic burdens, clerics and monasteries began to supply the missing ligatures of care—distributing food, buying timber, funding repairs, burying the dead when no family remained to claim them. The line between charity and administration blurred; necessity made new habits look like institutions.

Military logistics strained but did not snap. Garrisons were refilled from districts less afflicted; pay chests were lightened elsewhere to keep a frontier quiet here. Campaign timetables stretched: a spring offensive became a summer skirmish; a promised siege slipped into the next year. Ships carried soldiers one way and grain the other, and often as not, they also carried the sickness.

Yet the command structure learned to factor absence into plans, to field forces that assumed loss, and still to hold the crucial forts and passes. Recovery arrived unevenly. Coastal hubs revived when shipping resumed; inland towns waited on the return of herds and harvests.

Some regions learned quickly to rotate labor, to pair orphaned fields with land-poor neighbors, to accept partial harvests and count them as victories. Elsewhere, entire quarters remained shuttered for years, their bathhouses dry, their streets narrowed by the silent drift of wind-blown dust. What returned first was not abundance but predictability: markets on the same days, tolls at the same bridges, the same bell at dusk.

In law and custom, the plague left its print. Contracts lengthened to share risk; leases added clauses for interruption; guild rules softened to admit new hands and keep skills from dying out. Land changed owners more frequently; archives show chains of transfer that once took generations now compressed into a decade.

Yet beneath the churn lay a stubborn continuity: roads still carried goods, scribes still tallied dues, ships still beat the same coastal tracks. The empire contracted, adapted, and kept going.

What endured, finally, was a new way of measuring strength. Not by surplus alone, but by the capacity to absorb shock: to collect less and still pay troops; to rebuild slowly and still keep baths warm in winter; to bury the forgotten without forgetting oneself.

After the first terror receded, the state and its cities learned the discipline of scarcity—how to balance loss against order, so that the fabric held, thinner in places, patched in others, but serviceable still.

Echoes of the Plague: Memory, Faith, and the Shape of Survival

When the dying eased and the carts stopped creaking, the empire did not simply return to itself. The plague left behind more than empty houses and altered ledgers; it altered how time was felt. Years began to divide into a before and an after. What had first been described as an inexplicable calamity hardened in memory into a sign—proof that history could turn overnight, that cities could be humbled in a single season, and that fortune was no shield against invisible enemies.

Public language adapted first. Homilies and chronicles folded the catastrophe into a moral grammar, reading drought, earthquake, and pestilence as linked warnings. The pestis became a measure against which other troubles were weighed: sieges, tax burdens, even bad harvests were narrated in its shadow. Calendars filled with commemorations of deliverance; processions and fasts set a permanent rhythm of supplication and thanks.

In law and administration, too, a residue remained: remissions of tax, provisions for orphans and abandoned estates, rules for inheritance when whole lines had vanished. The state that had counted men for armies now learned to count the missing.

Households reassembled with different shapes. Survivors inherited suddenly and unevenly; workshops reopened with fewer hands; neighborhoods learned new boundaries around absence. The vocabulary of care—nurses, gravediggers, stewards of the poor—became part of civic identity.

Monasteries grew in number and authority, not only as refuges but as keepers of memory, places where the names of the lost could be spoken and where divine mercy could be asked with regularity. The habit of intercession deepened; so did the expectation that catastrophe might return.

Over time, the empire repainted its past in the light of that lesson. Golden ages were remembered as healthier ages; decline was described in the language of contagion. Yet the same story that mourned also affirmed endurance. Courts resumed, fleets sailed, grain reached the harbors.

The rebuilt quarter or reopened market became its own argument—proof that order could be restored, that institutions could bend without breaking. Survival itself turned into policy: redundancy in supply lines, reserves of grain and cash, the quiet art of governing through shortage.

Thus the plague’s legacy was double. It taught fear of how quickly life could be undone, and it taught confidence in how much could be remade. Between those poles—penitence and pragmatism—Byzantine society found a new poise.

The experience of pestilence became part of its moral weather, a permanent horizon of possibility that shaped prayer, law, and the telling of history. What began as a fever became a frame: a way of understanding trial and deliverance, fragility and repair, and the stubborn rhythm by which a great city learns to live with loss and still plan for tomorrow. (The Justinianic plague revisited, by Dionysios Stathakopoulos)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: