Shadows, Not Numbers: The Roman and Greek Experience of Time

Roman sundials did not divide the day into fixed hours. They followed the sun, stretching time in summer and compressing it in winter, shaping daily life through light rather than numbers.

Time in the Roman world did not tick forward in equal units. It lengthened and contracted with the seasons, expanding in summer and shrinking in winter, following the sun rather than the clock. Nowhere was this system more visible than in the Roman sundial.

Set into walls, placed in forums, or carried in portable form, sundials translated the movement of the sun into daily rhythm. They did not measure minutes, nor even fixed hours, but offered a changing structure of time that shaped how Romans worked, rested, and understood the passing of the day.

The Gnomon: The First Instrument of Time

The gnomon was the earliest known device used to measure time. Rather than tracking duration, it indicated a specific moment by the length of a shadow, not its direction. The term itself comes from Greek, meaning “pointer.” Unlike mechanical clocks, the gnomon could not measure intervals; it simply marked where the sun stood at a given point in the day.

Because of its extreme simplicity, identifying gnomons archaeologically is difficult. Finds are rare and geographically scattered, forcing historians to rely heavily on written sources and cautious interpretation of objects whose original purpose is not always clear.

Egypt and the Earliest Sundials

Written evidence shows that by around 1450 BCE, Egypt was already using gnomons—often in the form of obelisks—to measure time and regulate calendars. Even earlier, during the reign of Thutmose III, portable sundials appear to have been in use, though their exact form remains uncertain.

The oldest known sundial from this period is an L-shaped stone device, operating on the same principle as a gnomon. Oriented toward the sun, it used etched markings along its length to divide the day into hours based on the sun’s height. These hours were necessarily unequal, changing in length throughout the year as the sun’s declination shifted.

Precision and Innovation in China

China developed gnomon use to a remarkably high level of precision, as early as the first millennium BCE—and possibly much earlier. Chinese astronomers employed gnomons not only to measure time but to determine the astronomical meridian, identify solstices, and calculate the inclination of the ecliptic with striking accuracy.

To improve precision, Chinese engineers introduced a pierced gnomon, placing a disc with a circular hole at the top of the instrument. This eliminated the ambiguity caused by the sun’s penumbra, producing a sharp circular image whose centre could be accurately identified. By around 500 BCE, the height of gnomons was standardised by law, underscoring their importance in state-regulated astronomy.

The Gnomon Across Cultures

Beyond Egypt and China, evidence suggests widespread use of gnomons across the ancient world. In India, gnomons surrounded by concentric circles—later known as “Hindu circles”—were used to determine true south. In Mesopotamia, Babylonian and Chaldean astronomers were renowned for their expertise, and their knowledge influenced Greek practice.

Herodotus records that the Greeks learned from the Babylonians the use of the gnomon, the polos, and the division of the day into twelve parts, indicating a transmission of both technical and conceptual knowledge across cultures.

Gnomon and Polos: Two Different Principles

Ancient sources distinguish between the gnomon, which stands vertically, and the polos, whose style is aligned with the Earth’s axis. This distinction is crucial. Vertical gnomons cannot produce consistent hour measurements throughout the year, since the sun’s changing declination alters shadow length daily.

Polos-type dials, by contrast, allow for uniform hour measurement across seasons. Although little archaeological evidence survives, Herodotus’ reference suggests that such instruments may already have existed in Egypt by his time.

Unequal Hours and the Limits of Early Timekeeping

All early gnomon-based systems shared a fundamental limitation: they reflected a world of unequal hours. The same “hour” differed in length from day to day, especially between summer and winter. Only with the development of axis-aligned styles did sundials begin to offer consistent readings across the year.

These limitations highlight an important point: early timekeeping was not about precision in the modern sense, but about structuring daily life in harmony with the sun’s movement.

Egyptian Portable Sundials and Mesopotamian Influence

Contemporary with Herodotus, Egypt employed small portable sundials of distinctive design. These instruments cast the shadow of a straight edge onto a horizontal surface marked with hour divisions, sometimes onto stepped planes resembling miniature staircases, or even onto both surfaces simultaneously. The stepped form of some examples strongly recalls Mesopotamian ziggurats, suggesting a possible Chaldean origin or influence.

One Egyptian portable dial from the sixth century BCE displays this stepped structure clearly, while later examples show increasing sophistication. A fourth-century BCE dial represents a major technical advance: instead of a flat surface, the shadow fell on an inclined plane, marked with hour lines adjusted for different months.

This design marks the first known attempt in gnomonics to account explicitly for solar declination, recognising that the sun’s height changes throughout the year.

Accounting for the Sun’s Seasonal Movement

These later Egyptian dials represent a significant conceptual shift. Earlier instruments required careful orientation toward the sun before use, but they did not correct for seasonal variation. By contrast, the inclined-plane dial incorporated monthly scales, allowing more accurate readings across the year.

This development shows that ancient timekeeping was evolving beyond simple shadow measurement toward a deeper understanding of the sun’s motion. While still bound to unequal hours, these devices reveal an increasing awareness of astronomical regularity and a growing ambition to reconcile daily timekeeping with the broader rhythms of the solar year.

Berossos and the Birth of the Hemispherical Sundial

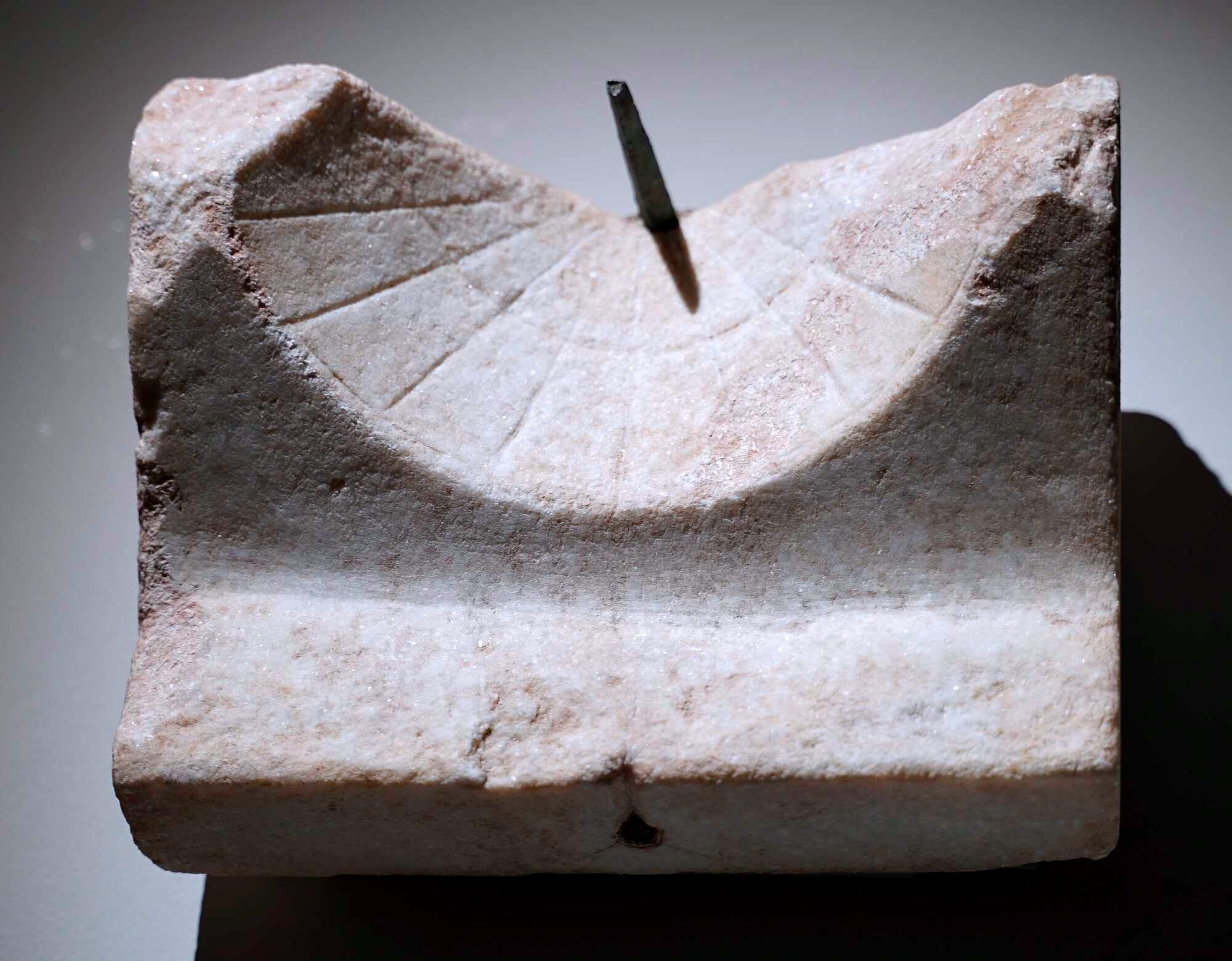

In the third century BCE, the priest Berossos introduced one of the most conceptually sophisticated sundials of antiquity. Working in Egypt, he designed a dial carved as a hemisphere hollowed into a stone block, with a gnomon positioned so that its tip lay at the exact centre of correspondence between the celestial dome and the hollowed surface. The hemisphere functioned as a miniature image of the sky itself: every point on its interior mirrored a point on the celestial vault.

As the sun traced its daily arc across the sky, its shadow described a corresponding arc inside the hemisphere. Berossos marked within the dial the solar paths of the equinoxes and solstices, then divided the resulting bands into twelve seasonal hours, following the Chaldean convention. This allowed the dial to reflect changing solar declination across the year rather than relying on a single, fixed scale. The result was an instrument that translated celestial motion into readable time with remarkable precision.

This design, later known as the hemispherium, was conceived as a portable object and stripped of unnecessary mass. Berossos soon refined it further: since the lower portion of the hemisphere never received sunlight, it was removed entirely, and the vertical gnomon was replaced with a horizontal one. This lighter, more economical variant became known as the hemicyclium.

Both forms spread rapidly throughout the ancient world. In Greece they were called heliotropes, while around 250 BCE Aristarchus of Samos developed a related hollow dial known as the scaphion, a term that later came to denote hollow sundials more generally. The longevity of the design is striking: according to the Arabic mathematician al-Battani, hemispherical dials of this type were still in use in the Islamic world as late as the tenth century CE.

Rome Learns to Live by the Sun

Rome encountered the sundial relatively late. The first public example appeared in 293 BCE, when a scaphion was set up near the temple of Jupiter Quirinus. Around thirty years later, during the First Punic War, another sundial was brought to Rome as spoils from Catana, a city of Greek foundation. The dial was almost certainly Greek in origin and was erected in a public space, where it drew attention as a striking novelty.

The instrument, however, had been calculated for the latitude of Sicily. In Rome, it could not mark the hours correctly. Despite this, the error went unnoticed for nearly a century. Pliny the Elder later reported the episode with pointed irony, remarking on Rome’s readiness to adopt a technical device without fully grasping the science on which it depended.

Only under Marcus Philippus, whose duties included supervision of public timekeeping, was the problem properly recognised. He understood that a sundial had to be designed for the specific latitude in which it stood if it was to function accurately. Even then, the spread of sundials did not displace older methods. In the Field of Mars, the great obelisk set up by Augustus continued to operate as a monumental gnomon, and traditional shadow-casting devices remained in use for centuries. In Rome, innovation rarely erased habit.

“M. Varro says that the first sun-dial, erected for the use of the public, was fixed upon a column near the Rostra, in the time of the first Punic war, by the consul M. Valerius Messala, and that it was brought from the capture of Catina, in Sicily: this being thirty years after the date assigned to the dial of Papirius, and the year of Rome 491. The lines in this dial did not exactly agree with the hours; it served, however, as the regulator of the Roman time ninety-nine years, until Q. Marcius Philippus, who was censor with L. Paulus, placed one near it, which was more carefully arranged: an act which was most gratefully acknowledged, as one of the very best of his censorship. The hours, however, still remained a matter of uncertainty, whenever the weather happened to be cloudy, until the ensuing lustrum; at which time Scipio Nasica, the colleague of Lænas, by means of a clepsydra, was the first to divide the hours of the day and the night into equal parts: and this time-piece he placed under cover and dedicated, in the year of Rome 595; for so long a period had the Romans remained without any exact division of the day.”

That said, sundials multiplied rapidly enough to provoke irritation. A comic passage, probably by Plautus, preserves the voice of popular resentment at the new tyranny of measured time:

“Let the gods damn the first man who invented the hours, the first man who set up a sundial in this city! For our misfortune he has chopped up the day into slices. When I was young, there was no other clock but my belly. It was the best and most accurate clock; at its call we ate, unless there was nothing to eat. Now, even when food is plentiful, we eat only when it pleases the sun. The city is full of sundials, and yet most people crawl about half dead with hunger.”

Behind the humour lies a serious point. Roman sundials did more than measure daylight. They imposed an external rhythm on daily life, replacing bodily need with abstract hours. Time, once felt and negotiated, had become something observed, regulated, and obeyed. (“Sundials. History, theory and Practice” by Rene R.J.Rohr)

Time, Language, and the Shared Habits of Empire

By the second century CE, at the height of Rome’s longest stretch of peace and prosperity, an educated observer moving through the empire would quickly notice several unifying features beneath its enormous diversity. A relatively small but influential elite—drawn from an empire of some sixty million people—shared two principal languages: Latin in the West and Greek in the East. These languages shaped administration, literature, education, and intellectual life, creating a common cultural framework that stretched from Britain to Syria.

This elite also shared a strong and deeply rooted concern with measuring, recording, and controlling time. Romans and Greeks alike paid close attention to long-term cycles—days, months, years, even centuries—as well as to the finer divisions of day and night, especially hours. Through a combination of custom and imperial authority, the Julian calendar, introduced at Rome in 45 BCE, came to be used across the empire.

Yet this standardisation never fully erased older or regional traditions. Roman systems coexisted with alternative practices, including those inherited from Egyptian culture, allowing multiple temporal frameworks to operate side by side.

Shorter-term timekeeping was especially visible. Devices for measuring intervals—such as oil lamps designed to burn for set periods, or water clocks (Greek κλεψύδρα, Latin clepsydra)—were widely used. Most prominent of all, however, were sundials. Known in Greek as ὡρολόγιον and in Latin as horologium or solarium, these instruments were usually fixed stone installations rather than portable objects. They appeared in a wide variety of forms—spherical, conical, or flat—and were placed in highly visible settings: marketplaces, baths, gymnasia, theatres, shrines, private houses, and even tombs.

Public sundials were often installed at the initiative of magistrates, priests, or wealthy benefactors, who used them to display civic generosity and status. Beyond their practical role, many sundials were deliberately decorative, and some were monumental. A striking example is the large sundial erected at Aphrodisias in honour of Caracalla and his mother Julia Domna in the early third century CE.

In Italy, inscriptions reveal that the port city of Puteoli possessed a sundial originally funded by an emperor and later repaired at public expense—a reminder that these instruments were both functional and symbolic markers of urban identity.

Designing Time: How Roman Sundials Actually Worked

The underlying principles behind sundials in the Roman world were inherited from classical Greece, though their precise origin cannot be pinned to a single place or individual. At heart, the concept was deceptively simple: a vertical rod (gnomon) cast a shadow across a curved surface marked with lines, allowing the passage of the sun from dawn to dusk to be translated into divisions of the day. As the shadow moved, so too did time become visible.

Yet beneath this simplicity lay a far more sophisticated understanding. A sundial could only function properly if its design matched the specific location where it was installed. The height of the sun changes depending on where one stands on the earth’s curved surface – what later thinkers, and we today, call latitude. For accurate timekeeping, the geometry of the dial had to account for this variation.

In practice, however, such precision was difficult to achieve. Many fixed sundials in the Roman world were not adjusted exactly to the latitude of their location. Even so, this rarely caused concern. Minor discrepancies were hard to notice in everyday use, and only significant differences in latitude would have produced errors obvious enough to attract attention. As a result, sundials were not normally inscribed with the place or latitude for which they had been designed.

Seasonal Hours and the Roman Day

Romans and Greeks divided daylight according to a convention inherited from Babylon: the day was split into twelve “hours,” beginning at sunrise, with noon marking the start of the sixth hour. These were not hours of fixed length, as we understand them today. Instead, they were seasonal hours – twelve equal divisions of daylight, regardless of how long the day actually was.

Because the length of daylight changes with both latitude and season, the length of an hour also changed. While water clocks (clepsydrae) could measure fixed intervals, there was no empire-wide standard for defining an hour, let alone subdividing it. Most sundials simply reflected the changing rhythm of the sun.

At Rome, this variation was striking. Around the winter solstice, daylight shrank to just over nine modern hours; at the summer solstice, it expanded to more than fifteen. As a result, a single “hour” could last as little as three-quarters of a modern hour in winter, or stretch to roughly one and a quarter hours in summer. Further north, these contrasts became even more pronounced.

For Roman users, this fluidity was not a flaw but a feature. Time was understood as something shaped by nature, place, and season – not as a fixed, mechanical quantity. Sundials made this visible every day, reminding their users that the passing of time was inseparable from the movement of the sun itself.

Well before the first century BCE, timekeeping in the Roman world was no longer tied exclusively to fixed stone monuments in forums and sanctuaries. As Vitruvius makes clear, portable sundials were already familiar objects, discussed as practical instruments suitable for travel rather than as novel inventions. Although the technical treatises he alludes to have not survived, Vitruvius’ casual references suggest that such devices were well established by his lifetime.

These portable sundials took a surprising variety of forms. Some were designed for use at a single latitude, others could be adjusted for different regions, reflecting an advanced understanding of how the sun’s path changes across the earth’s surface. Archaeological finds confirm this diversity. Compact cylindrical sundials, sometimes made of bone, combined portability with precision.

One example from northern Italy, discovered in the tomb of a Roman oculist, was carefully calibrated for the local latitude and marked with the months of the Julian calendar and seasonal hours. Its correct identification as a sundial only in the late twentieth century overturned the long-held assumption that such instruments were a medieval invention.

Other portable designs were equally ingenious. Small bronze “pillbox” sundials used a pinhole to project sunlight onto an internal scale, while more complex suspended models allowed users to adjust for both latitude and season by rotating internal discs marked with geographic names and solar markers. These instruments required the user to know where they were and roughly what time of year it was, but rewarded that knowledge with remarkably accurate readings.

Reading Time in Stone: Deciphering Portable Sundials with Modern Imaging

Recent advances in reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) have transformed the study of Roman portable sundials. Where erosion and surface damage once rendered inscriptions unreadable, RTI now allows scholars to recover names, letters, and numerical details with a high degree of confidence. By stripping away colour and enhancing surface relief through specular imaging, this technique reveals incised lettering as stark, high-contrast forms, making even minute traces of carving visible where the naked eye fails.

This technological breakthrough has clarified how geographic names and latitude figures were recorded on sundials whose inscriptions lack an obvious reading order. For consistency, modern tables arrange these names from lowest to highest latitude, even when the original sequence may have followed a different logic. Scholarly conventions are used to mark uncertainty: damaged or missing letters, ambiguous numerals, and apparent engraving errors are all carefully noted rather than silently corrected.

The recovered data are then set alongside ancient and modern reference systems. Latitude figures preserved on the sundials are compared with those recorded in Geography, compiled in the second century CE, while also being translated into modern degrees and minutes for comparison. This process highlights both the sophistication and the limits of ancient geographical knowledge.

Ptolemy’s fractional system, expressed in proportions rather than minutes, requires cautious conversion, and some regional latitude ranges reflect inference rather than precise measurement.

Finally, the lettering itself offers little help in dating these objects. Greek and Latin letterforms on portable sundials are remarkably consistent and deliberately classical, whether used as letters or numerals. The result is a body of evidence that resists easy chronological classification but gains clarity through careful imaging and comparison. RTI, in this context, does not merely enhance inscriptions – it restores lost connections between Roman timekeeping, geography, and the technical knowledge embedded in these deceptively small instruments. ("Roman Portable Sundials. The Empire in Your Hand" by Richard J. A. Talbert)

Roman sundials never promised precision in the modern sense, nor were they meant to. They translated the movement of the sun into a shared rhythm of work, rest, and expectation, tying human activity to season and place. In this world, time was not counted but observed, not abstracted but embedded in stone, shadow, and public space. Long before hours became numbers, they were lengths of light—experienced differently each day, yet familiar to all who lived by the sun.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: