Rome’s Greatest Name You Rarely Hear

Power does not always announce itself. Sometimes it works quietly, close to the center of events, shaping outcomes while leaving few traces behind

Some figures leave their mark not through proclamations or crowns, but through endurance, precision, and an instinct for action at the right moment. They stand close to power without ever claiming it, shaping events while remaining deliberately in the background. In an age remembered for emperors and dynasties, one such presence helped define an era—through loyalty, labor, and a vision that outlasted the men who ruled.

A Battle That Would Decide an Age

Out on the open water, the approaching fleet was already visible. The sight was formidable and unsettling. Around two hundred ships advanced directly toward his own, moving fast and clearly intent on annihilation. Their vessels were larger, heavier, and more imposing.

Among them stood one ship in particular, marked by a purple sail and adorned with gold, catching the light of the sun. On board was Cleopatra VII, Queen of Egypt. Somewhere within the advancing line sailed the Roman ship carrying his sworn adversary, Marcus Antonius.

Both sides had committed themselves fully on this second day of September, 31 BCE. Beyond the narrow mouth of the Ambracian Gulf, the waters were unsettled, and the two fleets—matched closely in strength—were about to collide. Only one would emerge victorious. The consequences reached far beyond the men on deck. The battle would decide not only the fate of its commanders, but the future of Egypt as an independent power and the direction of the Roman world itself.

Victory would clear the path for his closest ally—Julius Caesar’s adopted heir and bearer of his name—to eliminate his rivals and return to Rome as its saviour. Defeat, by contrast, threatened the division of Roman power, the loss of the eastern provinces, alliances with hostile kings, perhaps even Parthia, and the strangling of Rome through the denial of grain and revenue. He himself might not survive the day.

During the previous decade, he had earned the complete trust of his friend. That confidence had placed upon him the responsibility for this decisive engagement. He was no stranger to naval warfare, yet he understood that experience offered no guarantees. On this day there was no room for error. One certainty remained: he would not relent until the task entrusted to him was finished.

As the ship rose and fell with the swell, he felt the wind strengthen over his left shoulder, blowing in from the northwest. It was the breeze he had anticipated—and on which he was counting.

Caesar’s commander was ready.

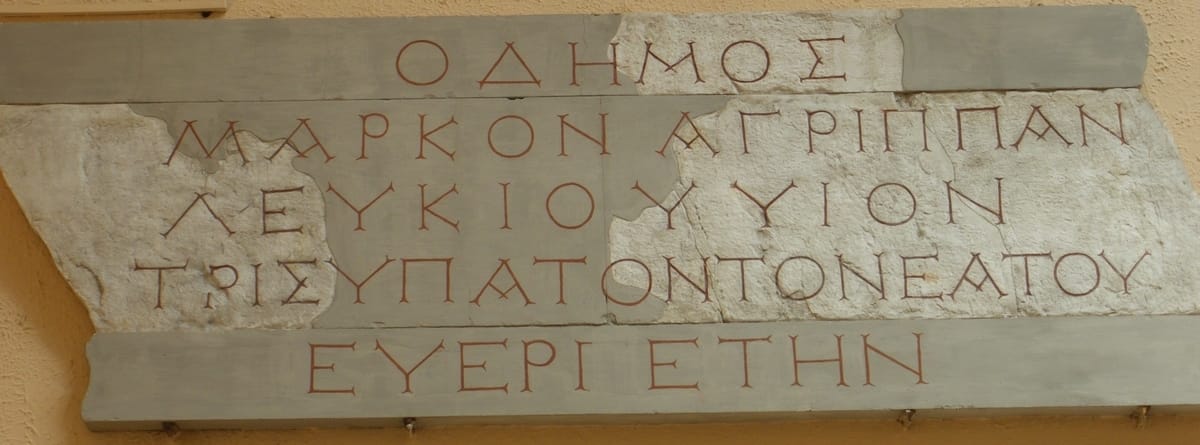

His name was Marcus Agrippa.

An Outsider Shaped by Obscurity and Crisis

Marcus Agrippa’s early life emerges from the sources as a study in deliberate obscurity. Even basic facts—his birthplace and exact year of birth—remain uncertain, a rarity for a man who would later stand at the center of Roman power. Ancient authors preserve only conjecture: central or southern Italy is usually assumed, with locations such as Arpi in Apulia or Arpinum in Latium proposed on linguistic grounds alone. What is clear is that he was not born in Rome, a fact that marked him as an outsider in a society deeply conscious of pedigree and place.

His family background offered little prestige. Agrippa belonged to the gens Vipsania, an obscure clan without a recorded lineage. He himself seems to have actively downplayed this connection, dropping the family name and presenting himself simply as “Agrippa.” Later anecdotes suggest that his father’s humble origins were a source of embarrassment—enough to invite jokes in court and pointed remarks in literary sources.

Even so, Agrippa retained his cognomen with pride. According to Pliny the Elder, the name “Agrippa” was associated with a difficult birth, feet first, a condition thought ominous in antiquity. That he survived—and prospered—made him, in Pliny’s words, an exception to the rule.

Despite this modest background, Agrippa received a proper Roman education. Like other boys of means, he learned reading, writing, arithmetic, and later advanced literary studies under a grammaticus, engaging with Greek and Latin texts that blended poetry, history, philosophy, and science. He grew up immersed in stories of Rome’s early heroes and republican virtues, even as the political reality around him bore little resemblance to those ideals.

The Rome of Agrippa’s youth was unstable and violent. The Republic was increasingly dominated by a small number of powerful individuals who bent institutions to personal ambition. Civil war, political purges, and the use of private armies were no longer extraordinary events but recurring features of public life. Figures such as Marius, Sulla, Pompeius Magnus, Crassus, and Julius Caesar reshaped the political landscape through military success, personal wealth, and calculated defiance of traditional norms.

For a young man of humble origins, this environment was both dangerous and instructive. Advancement no longer depended solely on ancestry or senatorial tradition but on loyalty, competence, and the favor of powerful patrons. Agrippa’s formative years unfolded against a backdrop of social mobility won through conflict, where “new men” could rise spectacularly—and fall just as fast.

These conditions would later shape his career, forging a figure who combined personal discretion with absolute effectiveness, and who learned early that survival in Rome depended as much on restraint as on ambition.

Growing Up as the Republic Unraveled

The year traditionally assigned as the beginning of Agrippa’s life coincided with a moment of extraordinary tension in Rome’s political world. Across the Mediterranean, military victories expanded Roman territory and influence, while within the city the institutions of the Republic strained under the ambitions of powerful men. Triumphs abroad brought immense wealth and prestige, yet they also sharpened rivalries that would soon turn inward.

Rome itself was increasingly governed by personal alliances, legal improvisation, and public scandal. Political careers rose and fell through popular agitation, courtroom theatrics, and calculated acts of intimidation. Emergency powers were invoked with growing frequency, executions were carried out without trial, and exile became a common political weapon. The Senate struggled to maintain authority as populist legislation and private armies reshaped public life.

This was also a period in which extraordinary individuals dominated events. Military commanders accumulated provinces and loyal troops, while others leveraged wealth to control elections and juries. The old balance between Senate, magistrates, and people fractured as civil violence became an accepted means of resolving disputes. By the time Agrippa reached adulthood, the Republic he inherited was no longer the one celebrated in Roman moral tradition, but a state edging toward rule by force and personal loyalty.

For a young man of obscure origin, this environment offered both danger and opportunity. Noble lineage mattered less than discipline, reliability, and effectiveness. The values that once defined Roman leadership were being rewritten, and those who would shape the next political order were already learning their lessons in a world where survival depended on choosing the right cause—and serving it without hesitation.

Formed by War and Patronage: Agrippa’s Early Path to Power

Agrippa entered adulthood during Rome’s final collapse into civil war. At fifteen, he assumed the toga of citizenship just as Caesar seized control of Italy, placing the city and its institutions under military dominance. Around this time, Agrippa formed a decisive friendship with a boy of similar age: Gaius Octavius, Caesar’s great-nephew and future heir. Their bond, forged early and tested repeatedly, would shape the political future of Rome.

While still completing his education—particularly in rhetoric, a skill essential to public life—Agrippa lived through the rapid dismantling of the Republican order. Caesar’s victories over Pompeius at Pharsalus, his campaigns in Egypt, Asia Minor, and Africa, and his return to Rome as undisputed master of the state formed the backdrop of Agrippa’s youth. These events exposed him early to the realities of power: clemency used as strategy, violence as spectacle, and loyalty rewarded selectively.

Agrippa’s personal stake in the conflict became clear when his brother Lucius fought on the opposing side in Africa. Through Octavius’ intervention, Caesar spared Lucius—an episode that reveals both the value of Agrippa’s connection and the beginning of his quiet integration into Caesar’s circle. Though Agrippa himself received no formal honors at this stage, he was now visible to the regime.

His possible first military experience came during Caesar’s final campaign in Hispania against the sons of Pompeius. Whether Agrippa fought at Munda or arrived too late, the episode illustrates the uncertainty of his early career: opportunity was close, but advancement was not yet guaranteed. Unlike Octavius, who was publicly favored and promoted, Agrippa remained in the background—observing, learning, and waiting.

What defines this period is not command or glory, but preparation. Agrippa’s youth unfolded amid relentless warfare, political purges, and the concentration of power in single hands. He absorbed military practice, rhetorical training, and the mechanics of patronage at the highest level. By the time the Republic finally fell, Agrippa was already formed by its violence—and positioned to serve the new order that followed.

Apprenticeship in War and Power

This campaign marked the final war of Julius Caesar’s career. With resistance in Hispania extinguished, there was no reason to linger. Caesar moved swiftly, arranging transport from Carthago Nova along the coast toward Massilia and onward to Rome. According to Nikolaos of Damaskos, Octavius was placed aboard Caesar’s own vessel, accompanied by a small household of slaves and, by personal choice, several close companions.

Far from resenting this familiarity, Caesar praised his great-nephew for surrounding himself with observant and capable men, noting approvingly his concern for reputation and character.

Among those companions were two figures who would shape Octavius’ future: Quintus Salvidienus Rufus, a man of obscure origins already serving in Caesar’s military sphere, and Marcus Agrippa. Their presence signals that Agrippa was already part of an intimate circle forming around the young heir.

After reaching Rome, the group remained briefly in the city. Octavius’ social standing rose sharply during this period, yet he maintained close ties with his companions. Within months, they departed again—this time for Apollonia in Illyricum. There, Caesar intended his great-nephew to continue learning the practical arts of war while preparations were underway for campaigns against the Getae and Parthians.

Apollonia proved an ideal setting. A well-governed coastal city with a deep harbor and long-standing Greek and Roman traditions, it offered both military instruction and intellectual refinement. Octavius trained regularly with cavalry units drawn from nearby legions, while senior officers visited him as a relative of Caesar. Through these interactions, he developed early rapport with the army—a familiarity that would later prove decisive. Agrippa almost certainly trained alongside him, absorbing military discipline and command structures firsthand.

The city also served as a center of learning. Apollodorus of Pergamum continued to instruct Octavius in rhetoric, ensuring that military preparation was matched by intellectual formation. Between drills and study, the young men lived a life balanced between discipline and leisure.

One episode recorded by Suetonius captures the tone of these months. A celebrated astrologer named Theogenes lived in Apollonia, and Agrippa visited him first. After studying him, the astrologer predicted “great and almost incredible fortunes.” Octavius hesitated to follow, fearing an unfavorable comparison, but was eventually persuaded. Without revealing his identity, he submitted to the same scrutiny. Theogenes reportedly rose and knelt before him in reverence, immediately recognizing his destiny. Whether dismissed as youthful amusement or taken seriously, the moment lingered.

The winter passed. After several months in Illyricum, a messenger arrived from Rome bearing a letter from Octavius’ mother. The news was devastating. Julius Caesar had been assassinated. Rome was in turmoil.

From that moment, nothing would remain as it had been.

Standing Beside an Heir in a Dangerous Vacuum

In the aftermath of Caesar’s assassination, Agrippa remained close to Octavius as events accelerated beyond anyone’s control. His role during these years is difficult to trace in detail, but the sources consistently place him at his friend’s side—as advisor, confidant, and loyal companion—while Octavius began his transformation from private citizen into political actor.

When news of the murder reached Apollonia, Octavius faced an immediate choice: accept the protection of loyal legions in Macedonia and march on Italy, or return quietly and assess the situation. Some of those around him—likely including Agrippa—urged decisive military action. Instead, Octavius chose a cautious course. Accompanied by Agrippa and Salvidienus, he sailed for Italy and entered the peninsula discreetly, gauging the mood before committing himself.

In Rome, power had not passed to the assassins but was being consolidated by Marcus Antonius. Through calculated compromise, Antonius secured an amnesty for the conspirators, took control of Caesar’s papers and estate, and positioned himself as the executor of the dictator’s legacy. His funeral oration ignited popular fury, driving the assassins from the city, while behind the scenes he manipulated appointments and finances to strengthen his grip on the state.

Only gradually did Octavius learn the full implications of Caesar’s will. He was not merely a beneficiary, but the dictator’s posthumously adopted son and principal heir, entitled to three quarters of the estate and to Caesar’s name. From this moment, Octavius became Gaius Julius Caesar in law and identity. Agrippa, still barely twenty, now found himself bound to a man whose political weight had changed overnight.

The inheritance brought both opportunity and danger. Antonius delayed the formal adoption process, retained control of Caesar’s funds, and openly belittled the young heir. Yet Octavius proved unexpectedly resolute. He committed himself to honoring Caesar’s promises to the people, raising funds through loans and asset sales when Antonius withheld the treasury. Veterans rallied to him, drawn by Caesar’s name and memory.

A turning point came during the games held in Caesar’s honor, when a comet appeared in the sky. Interpreted as a sign of Caesar’s divinity, it provided Octavius with a powerful symbolic tool. By presenting his adoptive father as a god while portraying himself as a lawful, restrained successor, he began shaping a new political narrative. Agrippa’s precise role in crafting this messaging remains unclear, but his presence within Octavius’ inner circle suggests he was witnessing—if not yet directing—the mechanics of power and propaganda at close range.

As tensions with Antonius sharpened, reconciliation proved temporary and fragile. The two men were no longer allies but rivals, competing for legitimacy, loyalty, and control of Caesar’s legacy. When Antonius moved to secure the Macedonian legions and alienated them through brutality and misjudgment, the balance of power began to shift again.

For Agrippa, these years marked a silent apprenticeship. He was not yet a commander or magistrate, but he was learning how Rome worked when law collapsed into force, how reputation could outweigh office, and how loyalty—to the right man, at the right moment—could shape an entire life.

From Advisor to Power Broker: Agrippa in the Mutinese Crisis (43 BCE)

After Caesar’s assassination, Rome slid rapidly toward another civil war. As tensions between Antony and Caesar’s heir escalated, Agrippa emerged as one of the young Caesar’s most trusted advisers, now firmly embedded within his inner circle. Alongside figures such as Maecenas and Salvidienus, Agrippa helped shape strategy at a moment when political survival depended as much on military loyalty as on senatorial legitimacy.

The confrontation culminated in the Mutinese War, sparked when Antony besieged Decimus Brutus at Mutina. The Senate, seeking to contain Antony while underestimating Caesar’s ambition, relied on Caesar’s legions to relieve the city. Agrippa accompanied Caesar during the campaign, which ended in Antony’s defeat and retreat beyond the Alps—but also in the deaths of both consuls, Hirtius and Pansa. With no senior magistrates left alive, real power shifted abruptly.

The Senate attempted to sideline Caesar once Antony appeared neutralized, granting honors to Brutus instead and denying Caesar a triumph. The miscalculation proved fatal. Backed by loyal legions and guided by advisers such as Agrippa, Caesar forced the issue: at nineteen, he marched on Rome and secured the consulship by intimidation rather than persuasion. Shortly afterward, his formal adoption into the Julian line was finalized, completing his transformation from private citizen to political force.

For Agrippa, the Mutinese crisis marked a decisive transition. No longer merely a companion or junior supporter, he had become a constant presence at the side of a rising ruler—participating in decisions where military force, political maneuvering, and personal loyalty fused into a new kind of power.

Agrippa Steps Forward: Law, Loyalty, and Power After Caesar

After the consolidation of power following Mutina, Agrippa emerged publicly for the first time as a political actor in his own right. Under the Lex Pedia of 43 BCE, which formally outlawed Caesar’s assassins, he was entrusted with leading the prosecution of Gaius Cassius Longinus. Although Cassius was tried and condemned in absentia, the case marked Agrippa’s entry into Rome’s political arena, signaling the confidence placed in him by Caesar and his circle.

There is strong evidence that around this period Agrippa also held the tribunate, a post that granted him personal inviolability and significant legislative powers. If so, it would explain his ability to shield allies, obstruct hostile measures, and act decisively during a volatile transition in government—functions that directly served Caesar’s interests at a moment when legality and force were tightly interwoven.

During the proscriptions initiated by the Second Triumvirate, Agrippa distinguished himself by intervening to save at least one man from execution, successfully securing the removal of a condemned name from the lists. In an era defined by calculated violence and political terror, this episode stands out as a rare example of restraint exercised from within the machinery of power.

Agrippa remained at Caesar’s side during the campaigns against Brutus and Cassius, including at Philippi, where later sources record him attending Caesar during a serious illness. With the defeat of the conspirators and the reshaping of the Roman world under triumviral control, Agrippa returned to Italy alongside Caesar.

By this point, he was no longer merely a companion or confidant, but a trusted lieutenant whose role blended legal authority, political judgment, and personal loyalty—foundations upon which his later prominence would rest. (“Marcus Agrippa. Right-hand man of Caesar Augustus” by Lindsay Powell)

By the early 40s BCE, Marcus Agrippa had secured a position that owed nothing to ancestry and little to public display. He had moved from obscurity into the inner workings of power, not through office or rhetoric, but through steadiness, judgment, and an instinct for when silence mattered more than visibility. As Rome emerged from the chaos of civil war into a new political reality, Agrippa stood beside its future ruler not as a rival, nor as a figurehead, but as a constant presence—shaping outcomes while remaining deliberately out of sight. In an age defined by ambition, his influence was exercised differently, and it was precisely this quality that made it endure.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: