Nerva: The First of the Good Roman Emperors

Amid the ruins of Domitian’s tyranny, Nerva brought calm without conquest. His short reign restored justice, dignity, and trust—laying the quiet foundations for Rome’s most peaceful age.

When Domitian fell beneath the assassin’s blade in 96 A.D., Rome stood on the edge of chaos. The Senate, long humiliated and afraid, sought a man who could calm the storm without igniting another. Their choice was Marcus Cocceius Nerva — elderly, childless, and untainted by tyranny. In less than two years on the throne, he would repair a shattered empire, restore the Senate’s dignity, and set in motion a line of emperors that would carry Rome to its greatest heights.

The Fragile Art of Succession: From Domitian’s Death to Nerva’s Rise

A change in government is among the most perilous moments for any state’s stability. While modern democracies have developed mechanisms to manage transitions—through elections, transitions, or caretaker governments—autocracies remain vulnerable to turmoil, particularly at the death or overthrow of a ruler.

The Roman Empire exemplified this danger. Its lack of a fixed succession system meant that power could pass by heredity, election, or adoption, but each method carried risk. Sudden deaths, assassinations, and rival claimants frequently led to instability or civil war.

From Augustus to Nero, hereditary succession often ended in bloodshed, with few emperors dying natural deaths. When Nero’s suicide extinguished the Julio-Claudian line, the civil wars of 68–70 A.D. revealed the lethal consequences of a vacant throne. Vespasian’s victory restored temporary stability through a new hereditary line, yet Domitian’s eventual assassination reopened the same uncertainty: he left no heir, and his adopted cousins were mere boys.

To prevent another descent into civil conflict, conspirators swiftly elevated Marcus Cocceius Nerva—an elderly, childless senator whose very neutrality made him a safe choice. His adoption of the general Trajan would later secure a peaceful transition, but the years 96–98 A.D. remained a moment of profound tension. Rome stood on the edge of another civil war that, remarkably, never came.

The Emperor Who Calmed the Storm

Nerva was a man whose reputation for moderation promised stability without vengeance. Yet his age and frailty also made him a temporary solution to a deeper crisis: who would command Rome’s armies and hold together an empire accustomed to dynastic rule?

In the first months of his reign, Nerva sought to undo the harsh legacy of Domitian. He recalled exiles, restored confiscated properties, and promised a freer political climate. His coinage proclaimed libertas publica and concordia senatus populi Romani, signalling reconciliation between ruler and Senate.

But harmony proved fragile. The Praetorian Guard, furious that Domitian’s assassins went unpunished, rioted and forced Nerva to submit to their demands. The episode exposed the emperor’s weakness and made clear that the army, not the Senate, would decide Rome’s future.

To avert disaster, Nerva turned to the principle of adoption. In October 97 A.D., after private consultations across the empire’s command network, he adopted Marcus Ulpius Traianus — a younger general of proven loyalty — as his son and successor. The choice united Senate and army under a single figure and transformed a potential civil war into a peaceful transition. Nerva’s final months were quiet; when he died in January 98, Trajan’s accession was accepted without violence.

Though his reign lasted barely sixteen months, Nerva accomplished what few emperors before him had managed: he stabilized the empire without bloodshed.

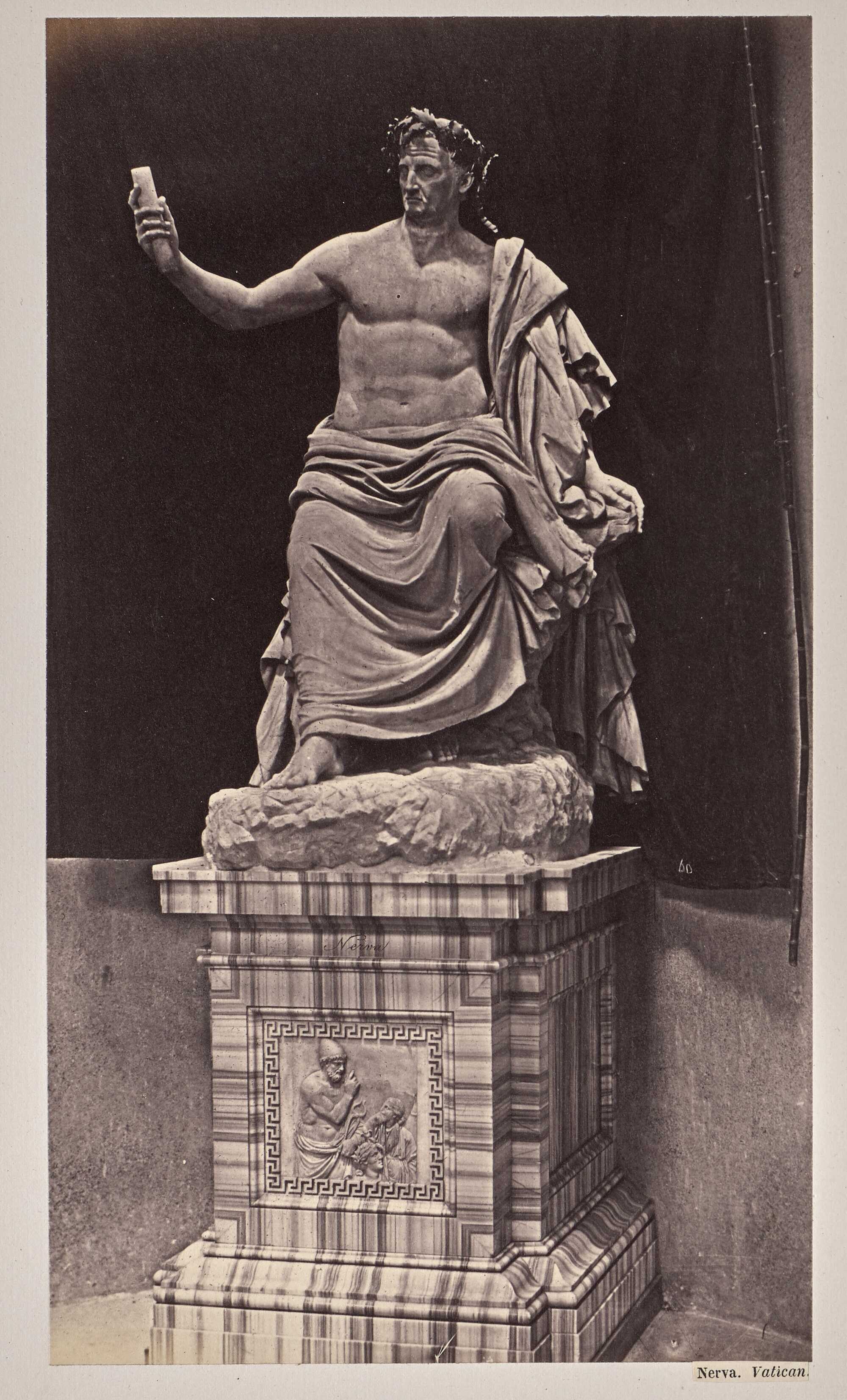

Bust of Roman Emperor Nerva. Credits: cascoly, Canva

By separating the throne from heredity and introducing a system of succession based on merit and consent, he became the first of the so-called “Five Good Emperors.” His brief rule marked the end of fear and the beginning of Rome’s most enduring age of peace.

Justice, Frugality, and the Care of Empire

Nerva’s approach to governance reflected moderation and moral repair after years of autocratic excess. He introduced reforms that restored public confidence in imperial justice and finance. Fiscal disputes were removed from imperial officials and reassigned to praetorian courts, ensuring fairer adjudication under senatorial oversight.

He also eased the burden of inheritance taxes, relieved financial pressures on citizens, and modified the fiscus Judaicus to prevent its abuse. To stabilize the treasury, he even sold palace furnishings and repurposed Domitian’s statues — gestures that symbolized restraint and accountability in an empire long accustomed to extravagance.

Determined to include the Senate in state affairs, Nerva created a commission of distinguished senators, among them Frontinus and Spurinna, to examine imperial finances and propose measures of economy. This body signaled a renewed partnership between emperor and aristocracy — a stark contrast to Domitian’s solitary rule. The commission’s work helped Nerva re-establish confidence that Rome could be governed by consultation rather than fear.

Though his reign was brief, Nerva ensured the completion and maintenance of essential public works. He continued Domitian’s construction of the Forum Transitorium, later known as the Forum of Nerva, linking the imperial fora into a continuous civic space. Projects on the Circus Maximus, aqueducts such as the Aqua Marcia and Anio Novus, and several provincial road systems were sustained without interruption, showing that stability, not grandeur, defined his architectural policy.

Coin legends such as Annona Augusta and Tutela Italiae reveal Nerva’s concern for Italy’s prosperity. He supported local economies, encouraged legacies to municipalities, and reduced taxation where possible. Though modest in scale, these measures reflected a broader vision of restoring Italy’s central role in the empire — a policy later developed under Trajan’s alimenta program. (Nerva and the Roman succession crisis of AD 96-99, by John D. Grainger)

Nerva’s Finances: Moderation Amid a Mirage of Abundance

Contrary to later tradition, the empire Nerva inherited was not bankrupt. Domitian had left a treasury in good condition, its revenues sustained by disciplined administration rather than waste.

Yet in the political upheaval that followed the assassination, Nerva’s government began spending rapidly — not from necessity, but to secure loyalty and calm public unrest. Lavish donatives and congiaria were paid to both the people and the Praetorian Guard, while tax remissions and new benefits were issued to win approval.

The Economy Commission that followed months later was therefore not an emergency measure to refill an empty treasury, but a corrective against the extravagance of Nerva’s early months in power. To symbolize change, Nerva melted Domitian’s gold and silver statues, sold imperial furnishings, and declared parts of the palace public property — acts meant less to restore finances than to project virtue and humility.

Despite gestures of frugality, spending continued through public works, road restoration, aqueduct maintenance, and generous civic relief. As aforementioned, his coinage reflected this moral and fiscal program, celebrating equitas, libertas, and fides publica.

Nerva’s short reign thus stood between two extremes: Domitian’s rigor and Trajan’s expansion. His reforms did not arise from crisis but from principle. By balancing generosity with restraint and preserving financial health while easing the burdens of citizens, he laid the fiscal and moral foundations of the peace that followed. (The Imperial Finances under Domitian, Nerva and Trajan, by Ronald Syme)

Symbols of Fairness and Freedom: Nerva’s Coinage as Moral Communication

The coinage of Nerva carried messages far beyond the value of metal. Among its most striking motifs were the paired figures of Aequitas and Iustitia—fairness and justice—appearing on gold, silver, and bronze issues throughout his short reign.

Rather than technical references to the purity of the coinage or the control of state finances, these images embodied the emperor’s character and ideals. The scales and cornucopia of Aequitas suggested balance and abundance, while Iustitia, holding a sceptre and branch, represented lawful judgment and mercy.

These symbols echoed the language of the age. Contemporary writers praised Nerva for his moderation, fairness, and respect for right conduct. The same moral tone appeared in public art: on the frieze of the Forum of Nerva, the figure of Aequitas is shown in a scene of judgment, linking the emperor’s name with the restoration of justice in public life. The imagery on the coins thus mirrored the virtues celebrated in verse and oratory—a ruler who ruled through equity rather than fear.

Alongside Aequitas and Iustitia, the personification of Libertas Publica held a central place in Nerva’s coinage. Depicted with the pilleus and vindicta, symbols of manumission, she proclaimed the end of oppression and the return of open speech and lawful governance.

Together, these personifications created a language of virtue that defined the new age. Nerva’s coins were not mere instruments of exchange, but miniature declarations that fairness, justice, and liberty had once again found their place in Rome. (Aequitas and Iustitia on the Coinage of Nerva: a Case of Visual Panegyric, by Nathan T. Elkins)

Nerva’s reign may have been brief, yet its impact was lasting. In a world exhausted by fear and excess, he governed through reason, restraint, and fairness. His adoption of Trajan secured the line of good emperors that followed, but his true legacy lay in proving that power, when tempered by virtue, could heal an empire.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: