Mistress of Rome: Servilia, Caesar, and the Politics of Passion

They whispered about her in marble halls—Servilia Caepionis, sister to Cato, mother to Brutus, lover to Caesar. The story of a woman whose silence echoed louder than a senator’s speech.

Caesar, gifted her a black pearl worth fortunes, and rumors claimed she had more influence in Rome than any consul. In the heart of a collapsing Republic, their affair wasn’t just scandalous, it was dangerous. Was it love, power, or both? And how did this forbidden relationship ripple through the downfall of Caesar himself?

A Letter in the Senate: Scandal, Suspicion, and a Sister’s Secret

The Roman Senate was no stranger to drama, but what happened during a tense debate in 64 B.C. could have come straight from a stage. As tempers flared over the explosive Catiline Conspiracy, Julius Caesar found himself at odds with the fiercely moralistic Cato the Younger. (The Catilinarian conspiracy, sometimes Second Catilinarian conspiracy, was an attempted coup d'état by Lucius Sergius Catilina (Catiline) to overthrow the Roman consuls of 63 BC – Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida – and forcibly assume control of the state in their stead.)

Just then, a note was quietly handed to Caesar—fueling Cato’s suspicion that his rival was conspiring with the traitors. Demanding that the letter be read aloud, Cato forced Caesar into a corner. But when the parchment was finally unfolded, it wasn’t a secret message from revolutionaries—it was a private love letter.

According to Plutarch’s Life of Cato the Younger, Caesar was initially reluctant to share the note, but when pressed, handed it to Cato himself. To Cato’s dismay, the letter turned out to be a personal missive from a woman—not the evidence of treason he had hoped for.

Plutarch does not name the sender, but given Caesar’s well-known affair with Servilia, Cato’s half-sister, many historians and storytellers have drawn the tantalizing conclusion that the letter came from her. Whether this moment was a personal humiliation for Cato or a clever move by Caesar to defuse suspicion, it reveals the deeply entangled nature of private relationships and public power in the final years of the Republic.

“Now, since we must not pass over even the slight tokens of character when we are delineating as it were a likeness of the soul, the story goes that on this occasion, when Caesar was eagerly engaged in a great struggle with Cato and the attention of the senate was fixed upon the two men, a little note was brought in from outside to Caesar.

Cato tried to fix suspicion upon the matter and alleged that it had something to do with the conspiracy, and bade him read the writing aloud.

Then Caesar handed the note to Cato, who stood near him. But when Cato had read the note, which was an unchaste letter from his sister Servilia to Caesar, with whom she was passionately and guiltily in love, he threw it to Caesar, saying, "Take it, thou sot," and then resumed his speech.

But as regards the women of his household Cato appears to have been wholly unfortunate. For this sister was in ill repute for her relations with Caesar; and the conduct of the other Servilia, also a sister of Cato, was still more unseemly.

She was the wife of Lucullus, a man of the highest repute in Rome, and had borne him a child, and yet she was banished from his house for unchastity.

And what was most disgraceful of all, even Cato's wife Atilia was not free from such transgressions, but although he had two children by her, he was forced to put her away because of her unseemly behaviour.”

Plutarch, The Life of Cato the Younger

Servilia: Power, Politics, and a Woman at the Heart of the Roman Republic

In the world of the Roman Republic, the word family (familia) carried meanings far more layered than our modern usage. As Susan Treggiari notes, in her book “Servilia and Her Family”, in Roman terms a familia could refer to everyone under the legal power of the household’s male head—including slaves, freedmen, and children—but not necessarily the wife.

A woman like Servilia, though often residing with her children, remained in law part of her father’s family. Descent, inheritance, and identity flowed through the male line, and Servilia took her name from her father, Quintus Servilius Caepio. But not all who shared that name were considered close kin.

Noble Blood and Mixed Lineage

Servilia was born into one of Rome’s most established aristocratic lines. Her father, Caepio, was Patrician, while her mother, Livia, was plebeian. The Servilii traced their mythic origins to Alba Longa—Rome’s legendary forerunner—and claimed kinship with Romulus himself.

Her male-line ancestors included C. Servilius Ahala, known for assassinating a would-be tyrant in defense of the Republic—a story her son Brutus would later brandish in justifying Caesar’s murder. But Servilia's family history was not all virtue and glory. The Caepiones were known for ambition, pride, and scandal.

Treggiari cautions us, however, that such negative portrayals often reflect political agendas or familial rivalries, not impartial truth.

A portrait of Susan Treggiari, photographed by Mark Ashworth. Photo courtesy of The Institute for Digital Archaeology

Servilia’s father, Caepio, had a fiery and turbulent political career. He clashed with tribunes, disrupted public votes, and stood trial for maiestas (treason against the Roman people), only to be acquitted. But the fall of her grandfather, also named Caepio—who lost the Roman standard at Arausio and was exiled—haunted the family’s fortunes. Despite these setbacks, the family’s wealth and influence endured.

Servilia’s early years were marked by her parents’ divorce and her mother’s remarriage to M. Porcius Cato, grandfather of the famous Cato the Younger. This shifted Servilia’s home life dramatically.

By the time she was a young child, Servilia had lived in at least three different Roman homes—first with her parents, then with her mother and new stepfather, and later with her maternal uncle Drusus. She grew up surrounded by influential figures and other children who would go on to shape Roman politics—most notably her half-brother Cato and her brother Caepio.

Treggiari paints a detailed picture of elite Roman childhood, filled with servants, paedagogi, wet nurses, and even slave playmates, some of whom Servilia may have legally owned. These relationships, more than blood alone, built the emotional texture of family life.

Memory, Myth, and Servilia’s Voice

Many anecdotes from this period, like the stories of Cato’s stoic defiance or childish games mimicking law courts—likely came from family recollection, passed down and recorded later by figures like Plutarch. Treggiari suggests that Servilia herself may have been the source for some of these tales, especially those later shared with her son, Brutus.

While elite Roman girls rarely appeared in historical texts, they absorbed political culture from an early age. Servilia, sharp and observant, grew up at the crossroads of domestic upheaval and public legacy. Her story, reveals the depth behind a woman so often remembered only as Caesar’s lover or Brutus’s mother.

Educating a Roman Lady: Servilia’s Intellectual and Moral Formation

The world in which Servilia came of age was intellectually rich, socially complex, and deeply stratified. Unlike modern schooling, Roman education unfolded largely within the home. Treggiari suggests that Servilia was likely educated alongside her siblings—including Cato the Younger—though she would have received separate instruction as she grew older:

“perhaps with favoured slaves or other noble children who came to the house.”

A Classical Curriculum for a Cultivated Woman

Servilia's education was typical for a Roman aristocratic woman—limited in some areas, but by no means trivial. She was most certainly “at least fairly fluent in Greek,” the mark of refinement and status in Roman elite circles.

While girls weren’t trained in oratory or legal rhetoric, they were expected to develop a graceful command of language through the study of poetry, drama, and select histories. Treggiari notes that she probably read “morally acceptable authors of good style” and enjoyed exposure to Greek lyric poetry, Euripides, Menander, Herodotus, and possibly even Plato. Latin literature was still developing during Servilia’s youth, but names like Ennius, Naevius, and Cato the Censor would have been present.

Later in life, Servilia could access a wider range of texts—including “the speeches and treatises of Cicero, the poetry of Catullus, Lucretius, Caesar’s commentaries, and even Varro on farming.” These were not merely private pleasures; social skill, elegant conversation, and literary taste were essential tools of aristocratic women.

Servilia’s intellectual upbringing occurred in a household overflowing with “books and music, dancing, or poetry reading as entertainments.”

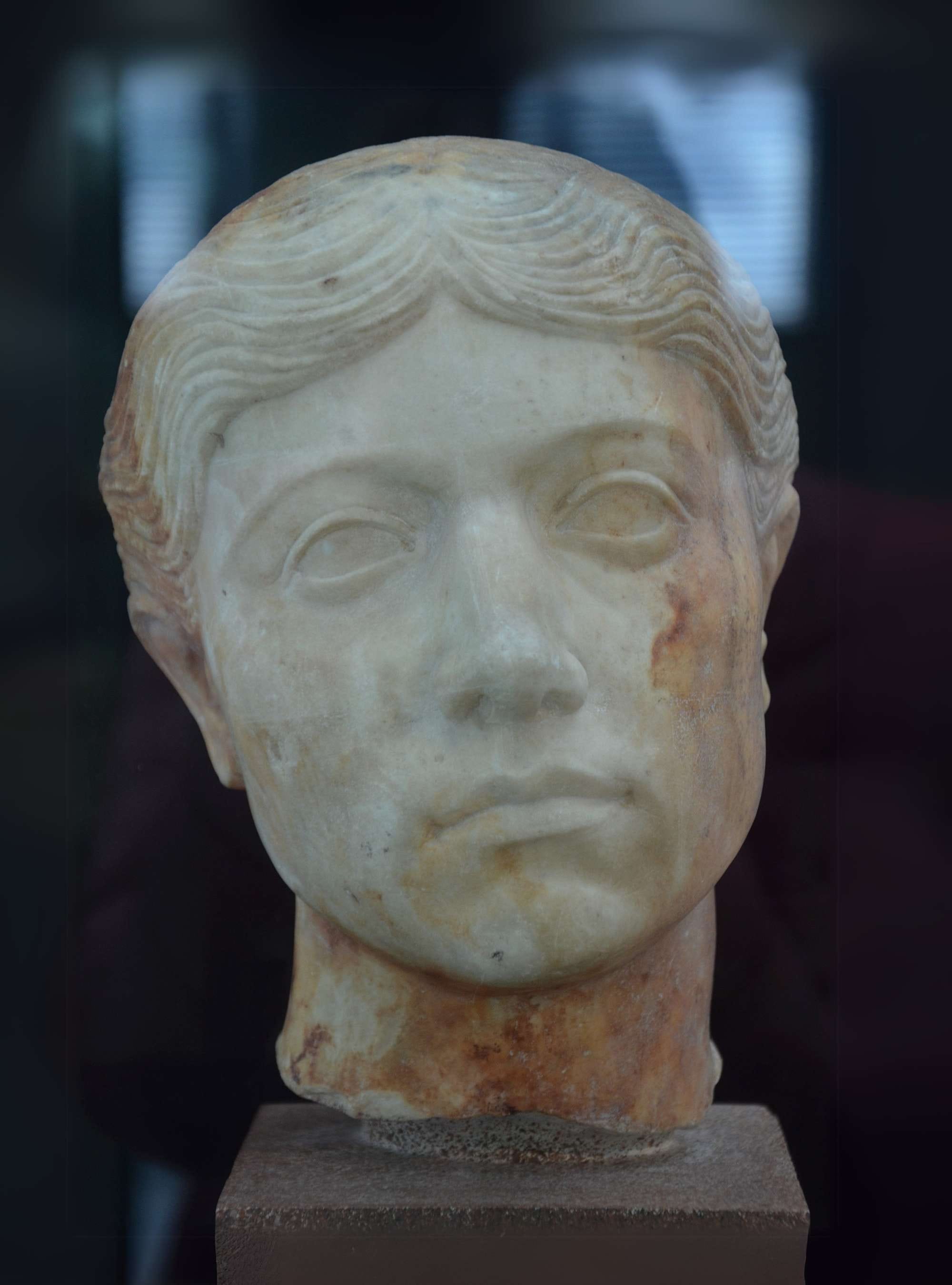

A possible representation of Servilia, browsing her villa’s wealthy library. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Sora

Her uncle Drusus’s home on the Palatine Hill was more than a private residence—it was a hub of political, intellectual, and cultural activity, filled with clients, philosophers, politicians, and tutors. As Treggiari writes, “The house needed to be full of men of all types… Accessibility and openness at all hours was vital.” From the noise of the salutatio in the atrium to the grandeur of marble-lined halls and libraries, Servilia grew up with a front-row seat to Roman elite life.

Domestic Training and the Discipline of Womanhood

In addition to literature and language, Servilia was expected to master the practical and symbolic arts of Roman femininity. She would have learned to “spin, weave, and embroider,” directing household tasks through slaves and freedwomen.

These skills were not trivial—they symbolized domestic virtue and the capacity to manage estates and staff. “Gradually,” Treggiari notes, “she will have picked up enough knowledge to make decisions about her property, money, and estates.”

Moral formation was equally essential. The Roman household was a place of memory and exempla, where children absorbed values through stories, art, and religious practices.

Servilia would have grown up surrounded by ancestral imagines and household gods. She would have learned not only about heroines like Lucretia, Cloelia, and Cornelia, but also about her own family’s figures—“the deeds of exemplary individuals” forming a moral compass.

One quote from Seneca, captures this philosophy beautifully:

“Let her become accustomed to your conversation, let her be moulded to your judgement; you will give her much, even if you give her nothing beyond your example.”

Far from being tucked away, Servilia would have been a silent observer of the Republic’s rhythms—morning visits, political strategy, elite conversation. Treggiari argues that Roman girls were not shielded from public life, but rather absorbed it early. They were trained, in quiet but powerful ways, to manage households, influence through family networks, and carry the values of their lineage into the next generation.

Pearls, Politics, and Passion: The Enduring Affair of Servilia and Julius Caesar

Few love affairs in Roman history have sparked more speculation—and left more of a historical footprint—than the relationship between Servilia Caepionis and Julius Caesar. This liaison was far more than a fleeting romance; it was a politically significant connection that endured through decades of war, power shifts, and personal upheaval.

Caesar, descended from the goddess Venus through Iulus, was known for his charm, ambition, and many affairs—yet “he loved Servilia best of all,” as Suetonius remarks. He gifted her a black pearl worth six million sesterces, a staggering sum, and later sold her estates at reduced prices, gestures that signal both affection and loyalty.

As aforementioned, Plutarch tells the famous story in which, during a Senate debate in 63 BC, a letter was handed to Caesar. Cato, suspicious of conspiracy, demanded it be read aloud—only to discover it was “a passionate and unrestrained letter from his sister Servilia.” Humiliated, he flung it back, calling Caesar a drunkard.

“That he was unbridled and extravagant in his intrigues is the general opinion, and that he seduced many illustrious women, among them Postumia, wife of Servius Sulpicius, Lollia, wife of Aulus Gabinius, Tertulla, wife of Marcus Crassus, and even Gnaeus Pompey's wife Mucia.

At all events there is no doubt that Pompey was taken to task by the elder and the younger Curio, as well as by many others, because through a desire for power he had afterwards married the daughter of a man on whose account he divorced a wife who had borne him three children, and whom he had often referred to with a groan as an Aegisthus.

But beyond all others Caesar loved Servilia, the mother of Marcus Brutus, for whom in his first consulship he bought a pearl costing six million sesterces.

During the civil war, too, besides other presents, he knocked down some fine estates to her in a public auction at a nominal price, and when some expressed their surprise at the low figure, Cicero wittily remarked: "It's a better bargain than you think, for there is a third off."

And in fact it was thought that Servilia was prostituting her own daughter Tertia to Caesar.”

Suetonius, The Life of Julius Caesar

The affair was not a scandal in the modern sense. Treggiari argues that in Rome’s elite circles, extramarital relationships—especially those conducted with discretion—were often tolerated. Servilia’s reputation was not damaged; in fact, her position was likely strengthened. “She was discreet, as Caesar and Cato were not,” Treggiari notes, distancing her from the more notorious women of her time like Clodia or Sempronia.

Whispers even circulated that Brutus, Servilia’s son, might have been Caesar’s child. Though modern scholarship deems this chronologically improbable, the enduring affection Caesar showed Brutus—sparing him after Pharsalus and favoring him politically—may stem from this quasi-paternal bond.

Treggiari places Servilia not as a passive figure in Caesar’s world, but as a woman of sharp political acumen, navigating the corridors of power with dignity. Their connection, she concludes, was not only physical but strategic, “held by him in enduring affection,” as Ronald Syme (a New Zealand-born historian and classicist) phrased it.

As Rome entered the stormy 60s B.C., Servilia stood at the center of an extraordinary network—half-sister to the uncompromising Cato, mother to the ambitious Brutus, and mistress to Julius Caesar, the rising star of the populares. In this decade of conspiracies, political trials, and shifting alliances, her presence in Roman public life was subtle but unmistakable.

In 63 B.C., while Cato pushed for the execution of the Catilinarian conspirators, her husband Silanus wavered in the Senate and Caesar, already Servilia’s lover, took a daringly moderate stance. That same year, Caesar was elected Pontifex Maximus against the seasoned Catulus, shocking the elite and fueling resentment.

As the political climate grew more volatile, Servilia may have played a balancing act—protecting her brother Cato while also passing information to Caesar. In 59, when Caesar married off his daughter Julia to Pompey and took Calpurnia as his own young bride, Servilia remained central in his life, receiving the legendary black pearl worth six million sesterces—as already mentioned—perhaps a parting gift, perhaps a token of enduring affection.

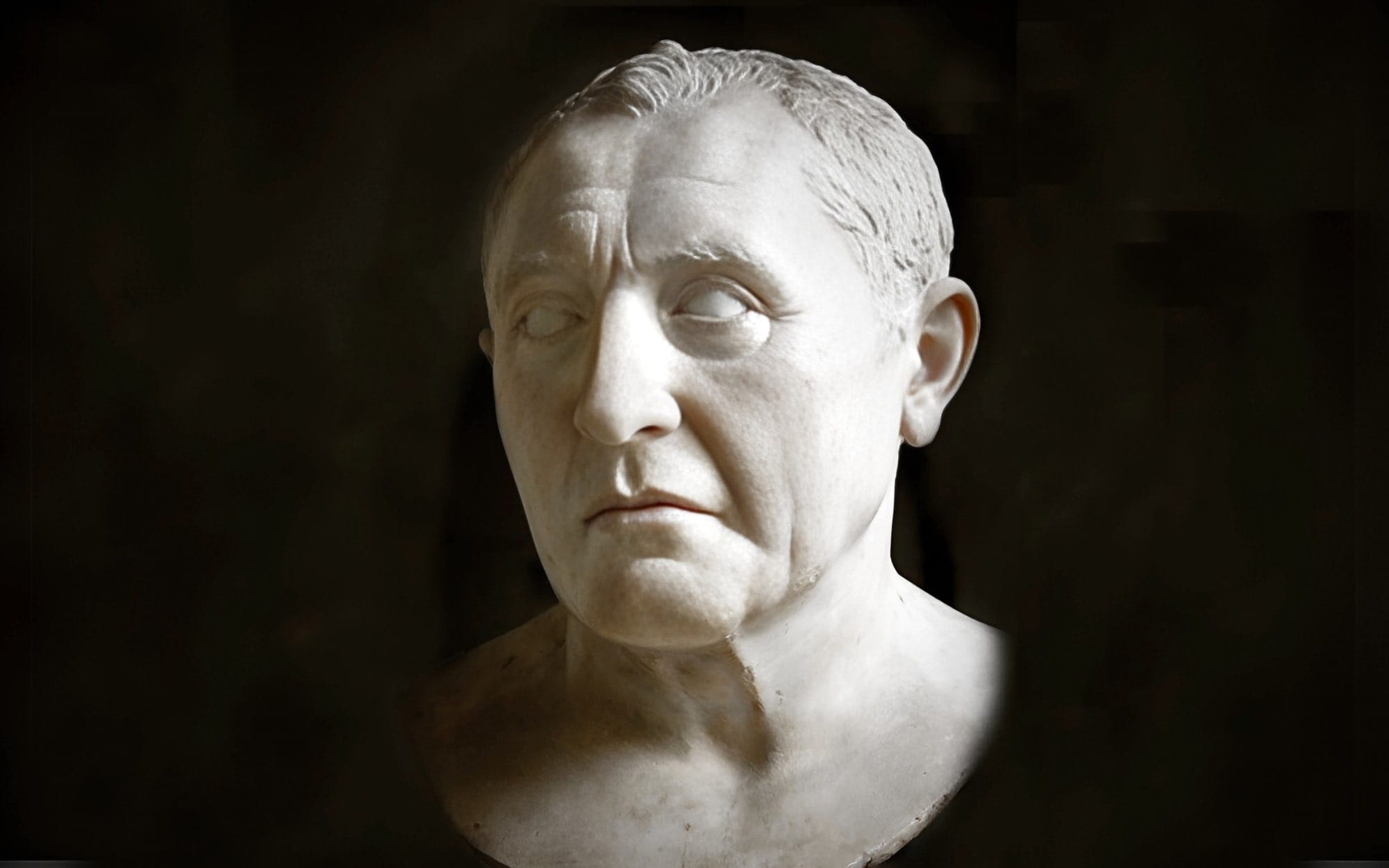

Cicero believed that she had enough influence to persuade Caesar to remove Brutus from a damaging political accusation, noting “a night and a night’s appeal for clemency had intervened.”

A bust of Cicero from the Glyptothek in Munich, Germany. Credits: Mary Harrsch, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

Though she never remarried, Servilia likely wielded considerable influence from her household—possibly hosting a salon of intellectuals and politicians akin to the famous gatherings of Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi. Her deep ties to the leading men of the Republic, both through blood and affection, made her one of the most quietly powerful women of her age. In the background of laws, trials, marriages, and wars, Servilia’s voice may not always be heard—but her hand can often be felt.

Daggers and Silence: Servilia in the Shadow of the Ides

On the eve of the Ides of March, Julius Caesar dined at the home of Lepidus. Among those present was Decimus Brutus, one of the soon-to-be assassins. Whether Servilia—his mother-in-law and Caesar’s long-time lover—was also there remains unknown.

What we do know is that the conversation turned to the ideal death, and Caesar replied:

“A sudden, unexpected one.”

The next morning, that very fate was granted to him—murdered beneath Pompey’s statue by conspirators including Servilia’s son, Brutus.

The ancient sources are largely silent on Servilia’s reaction, but as Treggiari poignantly writes, “This may have been the great love of her life, apart from her love of kin.” Her grief would have been magnified by the fact that it was her own son and son-in-law who plunged their blades into the man she had loved for over two decades. Yet Servilia did not retreat.

On the night of Caesar’s death, she and other kin of the assassins went from house to house, lobbying senators to intercede for their safety. Cicero believed Servilia had enough sway to remove Brutus’s name from a public denunciation just months earlier—a testament to her enduring influence. Though private emotion remains hidden, her actions reveal a fierce pragmatism. She likely hoped to protect both Brutus and Cassius, even as the tide turned in favor of Mark Antony.

According to Cicero, when he criticized the conspirators’ lack of a post-assassination plan in Servilia’s presence:

“her angry response showed she was sensitive on this point.”

Servilia would live through the backlash—rioting, funerals, miscarriages, and political fragmentation—with the same steel and strategy that marked her entire life. As Caesar’s body was burned and the streets turned violent, she may have mourned him in silence—but never without resolve.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: