If You Were Overweight in Ancient Rome, You Were Judged

From tyrants mocked for their bellies to scholars ridiculed for vanishing thinness, Roman writers turned body size into moral theatre. Fatness and emaciation were never neutral traits, but visible signs of luxury, weakness, discipline, or decline.

In the Roman world, the body was never merely physical. It was read, judged, and interpreted as evidence of character. Flesh could signify abundance or indulgence; thinness could suggest discipline, illness, or poverty. Moralists, physicians, satirists, and philosophers all treated the body as a visible register of virtue and vice. To speak of fatness or thinness was rarely to describe physiology alone. It was to speak about luxury, self-control, power, weakness, and the delicate balance the Romans called moderation.

Framing Fatness and Thinness – Modern Questions, Ancient Evidence

Debates in contemporary society about obesity – including proposals such as charging airline passengers for extra seats – reveal how body size can be treated not merely as a medical issue but as a matter of social functionality and moral judgment. While physical impairments associated with excess weight may be acknowledged, the cultural perception of personal responsibility often shapes public attitudes in ways distinct from other recognized disabilities.

At the same time, modern Western emphasis on health, fitness, and bodily perfection has also produced anxieties about extreme thinness, both in affluent societies and in contexts of undernourishment elsewhere.

From a historical perspective, these debates offer an opportunity rather than a platform for judgment. The study of Graeco-Roman antiquity allows scholars both to examine ancient societies with present-day questions in mind and to reconsider modern assumptions in light of ancient attitudes. The subject of fatness and thinness in classical antiquity remains relatively underexplored.

A comprehensive survey of Greek and Latin literature from the fifth century BCE to the sixth century CE reveals scattered but significant references to individuals described as overweight or emaciated. These references open questions about social class, gender, age, and the practical effects of body size on daily life.

The evidence operates on several levels. Literary texts reflect popular reactions – mockery, pity, admiration, or disgust – while medical and philosophical writings address bodily weight within broader discussions of self-control, health, and moral character. In some contexts, obesity is linked to excess and indulgence, while thinness may be associated with restraint, poverty, or ascetic virtue.

Christian authors introduce further nuances, especially in discussions of bodily discipline and spirituality. Distinguishing between lived reality and literary construction is not always straightforward, since mythological or rhetorical descriptions of bodies can illuminate cultural perceptions as much as they reflect actual conditions.

Recent scholarship has begun to address these issues more directly. Studies of philosophical discourse have emphasized themes of moderation and self-restraint, though they often focus more on moral behavior than on physical fatness itself. Research into Roman visual culture has examined representations of corpulence and emaciation in art, while anthropological approaches have highlighted how the material qualities of fat – softness, heaviness, visibility – shape perception across cultures.

Given the fragmentary and dispersed nature of the ancient evidence, a broad survey of genres and periods is necessary to avoid overly narrow conclusions.

Finally, the longue durée perspective is essential. Greek and Roman elites perceived their literary and medical traditions as part of a shared continuum, stretching from early classical texts through late antiquity. Although regional and chronological differences undoubtedly existed, they are often difficult to isolate in the surviving sources.

The history of fatness and thinness in antiquity was neither static nor uniform, yet it formed part of a durable cultural conversation about the body, health, morality, and social belonging – a conversation whose echoes extend far beyond the ancient world.

Food, Bones, and the Limits of Measuring Ancient Bodies

Any discussion of fatness and thinness in the Graeco-Roman world must begin with basic material conditions: average body size and access to food. Yet such questions have often been neglected in favour of literary or ideological analysis. Osteological research suggests an average height of roughly 1.67 metres for the Graeco-Roman population.

From skeletal remains, scholars can estimate stature, frame, and in some cases muscular development linked to heavy labour. Weight itself, however, leaves no direct trace. Body fat does not fossilise, and a small-framed individual might once have been heavy, just as a large-boned skeleton might have belonged to someone very lean.

Recent osteoarchaeological research has identified indirect indicators that may correlate with body mass, such as degenerative joint changes in the spine, hips, knees, and feet, as well as measurements of the femur in subadults. Obesity-related joint disease can sometimes offer clues.

Even so, no reliable estimates of obesity rates in classical antiquity exist. In contrast to studies of the Middle Ages, including skeletal analyses sometimes associated with monastic communities, antiquity remains largely unquantified in this respect.

Attempts to diagnose obesity retrospectively through art are equally uncertain. Some scholars have suggested that statuettes and terracottas display features consistent with specific medical conditions – ranging from endocrine disorders to fluid retention or forms of dwarfism. While such pathologies certainly existed in antiquity, identifying them confidently in artistic representations is methodologically precarious and rarely yields firm conclusions. Similar caution applies to images of extreme thinness, particularly in Hellenistic art.

Evidence for undernourishment, by contrast, appears more substantial. Osteological studies indicate cases of severe mobility impairment caused by insufficient nutrition, especially during childhood. Many researchers argue that calorie and protein shortages affected a large portion of the Roman population, likely increasing the prevalence of lean and even emaciated bodies.

Some estimates suggest that a significant share of adult men may have lacked the sustained physical capacity for heavy labour throughout the day – a claim sometimes supported by comparative data from early modern Europe. At the same time, overly optimistic reconstructions of ancient nutritional abundance have been criticised, and more balanced assessments emphasise methodological limits and regional variation.

Although it is impossible to assign Body Mass Index values to the ancient Mediterranean, broad comparisons suggest that the Graeco-Roman world more closely resembled modern societies with high rates of underweight populations rather than contemporary Western countries marked by widespread overweight and obesity. Corpulent individuals likely existed, but they were probably uncommon. Thinness – sometimes moderate, sometimes severe – would have been a far more familiar sight in everyday life.

Fat Kings and “Barbarian” Bodies: Between Admiration and Exoticism

Modern discussions of body size often rely on sharp contrasts: “western contempt versus non-western admiration,” or the supposed celebration of fatness in traditional societies set against contemporary Western ideals of slenderness. In popular imagination, this has produced the assumption that pre-modern cultures naturally admired corpulent rulers – the “fat, fertile and opulent king” as a symbol of abundance and power.

For the ancient Mediterranean, such ideas are often linked to prehistoric figurines, such as the so-called “Fat Lady” statues from Neolithic Malta or the Venus of Willendorf, as well as Egyptian depictions of the god Hapy with sagging breasts and a large belly. These images have been interpreted as symbols of fertility, prosperity, prestige, or even hope for a blessed afterlife.

Female figurines in particular have been associated with fertility, motherhood, femininity, and sexual appeal – although some of these readings have been challenged, especially by feminist scholarship. Even in societies sometimes described as admiring fatness, distinctions were often made between a “comfortable” amount of bodily fat and extreme overweight that impaired social functioning.

Strikingly, ancient literary evidence for deliberately fattened kings is extremely sparse. When fatness does appear in Greek and Roman sources, it is typically attributed not to admired rulers within the classical world, but to “strange and exotic” peoples.

Xenophon, for example, describes the Pontic Mossynoecians – whom he calls the “most barbarious nation” his soldiers encountered – as engaging in unfamiliar and shocking customs. Among these, he uniquely mentions the deliberate fattening of wealthy children:

“And when the Greeks, as they proceeded, were among the friendly Mossynoecians, they would exhibit to them fattened children of the wealthy inhabitants (παῖδας τῶν εὐδαιμόνων σιτευτούς), who had been nourished on boiled nuts and were soft and white to an extraordinary degree, and pretty nearly equal in length and breadth, with their backs adorned with many colours and their fore parts all tattooed with flower patterns.” (Xenophon, Anabasis 5.4.32; transl. C. Brownson)

Here, corpulence is not presented as a normative Greek or Roman ideal, but as part of a catalogue of foreign oddities.

A similar tone appears in the pseudo-Plutarchan On the Proverbs of the Alexandrians, which gathers examples under the maxim, “Each region has its own habits.” Among various exotic customs, we find:

“One finds different customs among different people – customs which are particular to one people. The inhabitants of Gordium elect the fattest among them (τὸν παχύτατον αὑτῶν) as king.” (ps.-Plutarch, De proverbiis Alexandrinorum 10)

To the best of our knowledge, these two passages are the only ancient references to fatness deliberately cultivated for royal or aristocratic prestige. Even when access to abundant food is portrayed as a sign of prosperity, or when Hellenistic kings and Roman emperors are depicted with large, well-fed bodies symbolising wealth and stability, this does not amount to an endorsement of deliberate fattening.

Instead, such practices are consistently framed as foreign. For Greek and Roman authors, corpulent rulers belonged to the realm of the exotic and the “barbarian,” a category often associated with weakness, excess, or lack of discipline. Fatness, in these texts, is not a stable symbol of prestige within classical culture, but part of a broader discourse about otherness.

Naming Fatness and Thinness: Vocabulary, Description, and the Problem of “Normality”

More than two centuries of classical lexicography, combined with digital research tools, make it relatively easy to assemble long lists of Greek and Latin words denoting fatness and thinness. For his study, “Writing the story of fatness and thinness in Graeco-Roman antiquity” Christian Laes examined roughly a thousand passages containing relevant search. Yet the apparent clarity of this vocabulary is deceptive.

Modern language about body size is often medicalised. Terms such as “overweight” or “obese” refer to technical definitions that can shift with changing standards – as demonstrated when revised medical guidelines in 1998 reclassified millions of people overnight. By contrast, ancient terminology belonged to a descriptive rather than a diagnostic sphere.

Greek and Roman physicians knew nothing of the Body Mass Index, and no fixed quantitative threshold defined corpulence or emaciation. Words such as “fat” or “slender” reflected relational judgments about bodily proportion rather than measurable categories.

Greek vocabulary for corpulence includes terms such as γαστρώδης or γαστροειδής, μεγαλόκοιλος, παχύς/παχύτης, πίειρα/πίων, πιμελώδης, πολύσαρκος/πολυσαρκία, προγάστωρ, σάρκινος, and ὑπέρσαρκος/ὑπερσάρκωμα. For thinness, words such as ἄσαρκος/ἀσαρκία, ἰσχνός/ἰσχνότης, λεπτός/λεπτότης, ὀλιγόσαρκος/ὀλιγoσαρκία, and σκληφρός appear.

Latin equivalents include adeps, crassus/crassitudo, obesus, (prae)pinguis, subcrassulus, and ventriosus for fat bodies, and macer/macritudo, macilentus, and strigosus for thin ones.

Yet many occurrences of these words do not describe human bodies at all. Soil can be called “fat,” cattle are described as corpulent, and even sounds or voices may be termed “fat” or “thin.” Certain medical terms, such as ὑπέρσαρκος (“covered with flesh”), often refer not to obesity but to scars, excess tissue, or pathological growths. Even words like βαρύς or gravis rarely signify bodily heaviness. Context is therefore crucial.

Ancient authors themselves occasionally reflected on bodily terminology in revealing ways. Galen, for example, articulates an ideal of proportion:

“Such a body is precisely in the middle of all excesses, so that the other types of bodies are understood and named in correlation with it. The body which is fat (τὸ παχὺ σῶμα) in comparison with this, is called fat (παχὺ), and in the same way the thin body (τὸ λεπτὸν) is named, the fleshy one and the one with little flesh (πολύσαρκόν τε καὶ ὀλιγόσαρκον), the fatty and the unyielding (καὶ πιμελῶδες, καὶ σκληρὸν) the weak, the hairy and the bare. None of these bodily types is in due proportion. But the body which equals the canon of Polycleites reaches the summit of complete symmetry. People who touch it do not sense experience anything weak nor harsh, neither hot nor cold; those who watch do not sense it as hairy or bare, fat or skinny (μήτε παχὺ, μήτε ἰσχνὸν), or with any other sort of asymmetry.” (Galen, Ars Medica 14)

In another passage, he distinguishes between healthy flesh and excess:

“Such as there exists both a proper disposition of the flesh in the human body (εὐσαρκία) and an excess of flesh (πολυσαρκία), there is a goodness of blood and fullness of blood.” (Galen, De Plenitudine 10)

These statements reflect the broader ideal of the aurea mediocritas – a preference for balance rather than extremes. Although ancient physicians lacked modern quantitative standards, they clearly regarded certain bodily states as preferable. Instead of speaking of “normality” in a statistical sense, they spoke of εὐσαρκία – a well-conditioned, properly proportioned body.

Other terms, such as ἔμμετρος (“in due measure”) or προσῆκον (“appropriate”), conveyed conformity to an ideal of proportion rather than deviation from a measurable norm.

Latin authors also grappled with bodily terminology. Aulus Gellius (Roman author and grammarian) observed that obesus originally carried the sense of “wasted away, lean, thin,” citing an archaic poetic usage. Grammarians debated whether pinguetudo was correct Latin. Suetonius even speculated that the name Galba might once have meant “enormously fat” (praepinguis) in a Gaulish context.

Taken together, the evidence reveals a vocabulary shaped less by medical classification than by ideals of symmetry, balance, and proportion. Fatness and thinness were not fixed categories defined by numbers, but relational descriptions anchored in broader cultural notions of harmony and excess.

Banqueting with Bodies: Athenaeus and the Moral Theatre of Fatness and Thinness

A remarkable concentration of anecdotes about unusually fat and unusually thin individuals appears in the Deipnosophistae (The Learned Banqueters) of Athenaeus of Naucratis. The temptation to treat these stories as straightforward social evidence is strong: they are vivid, detailed, and often irresistibly comic. Yet they must be read within the literary architecture of the work as a whole.

Significantly, stories about obese figures do not occur in Books 3 or 10, where gluttony and its socially destructive consequences are treated directly. Instead, corpulent rulers appear in Book 12, devoted to τρυφή – luxury, extravagance, and the moral incapacity to restrain desire. Athenaeus was not describing his own society but acting as an antiquarian compiler, gathering earlier anecdotes and embedding them within a moralised discourse on excess.

The portrait of Dionysius of Heraclea, tyrant from 337/6 to 306/5 BCE, illustrates this method. Athenaeus, quoting Nymphis, writes:

“Dionysius the son of Clearchus, who was the first tyrant of Heraclea, and who was himself afterwards tyrant of his country, grew enormously fat without perceiving it (ἔλαθεν ὑπερσαρκήσας), owing to his luxury and to his daily gluttony; so on account of his obesity (διὰ τὸ πάχος ) he was constantly oppressed by difficulty of breathing and a feeling of suffocation. On which account his physicians ordered thin needles of an exceedingly great length to be made, to be run into his sides and chest whenever he fell into a deeper sleep than usual… And he used to give answers to people who came to him, holding a chest in front of his body so as to conceal all the rest of his person, and leave only his face visible.” (Athenaeus)

Luxury and gluttony are presented as causes; breathlessness and immobility as consequences. The grotesque medical detail – long needles piercing insensitive flesh – heightens the sense of degeneration. Comic poets reinforce the image. One fragment describes him as a “fat pig,” another fantasises about lying fat and flat on one’s back – in pleasure.

Yet Athenaeus also notes that Dionysius ruled gently for thirty-three years. The juxtaposition invites reflection: does the mention of his humanity complicate expectations about the obese tyrant?

The same moralising pattern appears in the account of Ptolemy VIII Physcon. His nickname Physcon (“Potbelly”) encapsulates bodily mockery. Athenaeus stresses his long, effeminate sleeves, his difficulty walking, and the punning contrast between Euergetes (“Benefactor”) and Cacergetes (“Malefactor”).

A witticism records that he

“never went abroad on foot except on Scipio’s account,”

a phrase that also suggests walking with a staff. Corpulence becomes inseparable from decadence, ridicule, and political failure.

Other rulers follow: Ptolemy X, leaning on attendants yet dancing energetically at drinking parties; Magas of Cyrene, whose peaceful reign ended in breathlessness from indulgence. The Spartan Nauclides, is rebuked as useless in war – reinforcing the topos of incompatibility between obesity and military virtue.

Even the orator Python jokes that although he is enormous, his wife is bigger than him and that when they quarrel

“the whole house is not big enough for us.”

The pattern is clear: fatness is repeatedly tied to τρυφή, self-indulgence, softness, and political or moral failure. Even when Athenaeus remarks that it is

“better to be poor and thin than to be excessively rich”

and monstrous, this is not a blanket praise of thinness. It remains embedded in the ethical discourse on luxury.

Thinness, too, is filtered through literary and moral lenses. Names such as Leotrophides and Thumantis become proverbial for emaciation:

“the poor… are sacrificing… skinnier than Leotrophides or Thumantis.”

Comic poets mock playwrights sent to Hades as thin men already halfway to death. Cinesias is so tall and thin that he supposedly fastened a linden board to himself to prevent bending. The poet Philetas, required lead weights on his feet so that the wind would not carry him away. Such stories often originate in wordplay on poetic λεπτότης – fineness or subtlety – and transform stylistic criticism into bodily caricature.

Some anecdotes border on absurdity. Archestratos was so lean that he weighed “one obol.” Panaretus was yet free from illness, an explicit exception to the usual link between thinness and frailty. Hipponax, was paradoxically strong. Philippides became so synonymous with leanness that πεφιλιππιδῶσθαι meant “to be very thin,” almost dead.

The final moralising twist returns to excess:

“This fellow, then, because of his drunken habits and his fat body is called ‘Wineskin’ by all the natives.”

Throughout these anecdotes, bodily states mirror moral or social evaluation. Fatness signals luxury, softness, or tyranny; thinness signals insignificance, ridicule, or frailty. Yet both are literary constructions shaped by genre, satire, and inherited stereotypes.

Athenaeus’ banquet of bodies therefore offers less a statistical portrait of ancient physiques than a moral theatre in which flesh becomes metaphor. Obesity and emaciation are not neutral descriptions but narrative devices – ways of staging excess, weakness, ridicule, or irrelevance within a deeply literary culture.

Epigrammatic Extremes: Thinness as Spectacle in the Anthologia Palatina

Book 11 of the Anthologia Palatina preserves a striking cluster of epigrams on bodily “defects of stature,” where thin people – and sometimes dwarfs – are treated as comic curiosities. Compiled in the tenth century but preserving much earlier material, especially from the first century CE, these poems connect literary wit with contemporary medical discourse on λεπτοσύνη (thinness).

The epigrams exaggerate leanness into absurdity. Thin Stratonicus hangs himself from a reed spike. Lean Gaius is “the thinnest of the skeletons” in Hades, his bier nearly empty. Lean Marcus passes through one of Epicurus’ atoms and even disappears down a trumpet when blowing it. Chaeremon, “lighter than a straw ” is carried off by a breeze and caught in a spider’s web. Another trio of thin men compete in vanishing acts, one boasting:

“for I lose it if I am seen, since I am nothing but air”.

Behind the hyperbole lies a recognizable stereotype: the worn-out intellectual whose excessive study weakens the body. Medical writers such as Celsus had already linked bookish life to physical debility, and Athenaeus associated the λεπτός with poor diet and lack of strength. Thinness could signal not merely frailty but effeminacy, a deviation from the masculine ideal of muscular balance.

Patterns of Stigma: How “Fatness” Gets Used in Ancient Sources

Rather than building a simple list of “fat” individuals, it is necessary to group the evidence to show how overweight (and, less often, extreme thinness) functions as a label – a way to categorise, ridicule, moralise, or mark people as socially suspect.

Everyday identification (rare in papyri): bodily description appears often in documentary texts, but “fat” turns up only once – a suspect is described as “the shoemaker the fat one”.

Ethnic stereotyping: some groups are characterised as fleshy, soft, or “worthless-bodied,” while others are praised for policing belly-size. These “ethnic” claims likely blend observation with stereotype (for example, Albanians are linked to “fleshiness and weakness”, while Celts beyond the Alps supposedly punished young men who became big-bellied).

Fatness vs. military virtue: corpulence is repeatedly framed as incompatible with war-readiness. The sharpest formulation is preserved in a pseudo-Plutarchan anecdote:

“Therefore he hated fat men, and dismissed one of them, saying, that three or four shields would scarcely serve to secure his belly…”(Ps.-Plutarch, Regum et imperatorum apophthegmata 192c)

This sits in a wider tradition (Plato, Lucian and others) that prefers lean, sun-hardened fighters to bodies “bred in the shade.”

Athletes and “useful” bulk: wrestlers/boxers are sometimes treated as prone to weight gain and breathlessness; doctors warn that athletic regimes and retirement can produce fatness. A memorable Christian contrast appears in Basil, opposing the well-fed athlete to the ascetic ideal:

“contrary to the well fed and smoothly skinned athletes, the Christians… must be noticeable by… thin bodies.”

Political invective: fatness can be weaponised (Demades, Cato vs. Veturius, Cicero on Cassius/Antony, Juvenal on Montanus), yet it is relatively scarce compared with broader charges like luxury, gluttony, and drunkenness – overweight often appears as a consequence rather than the core accusation.

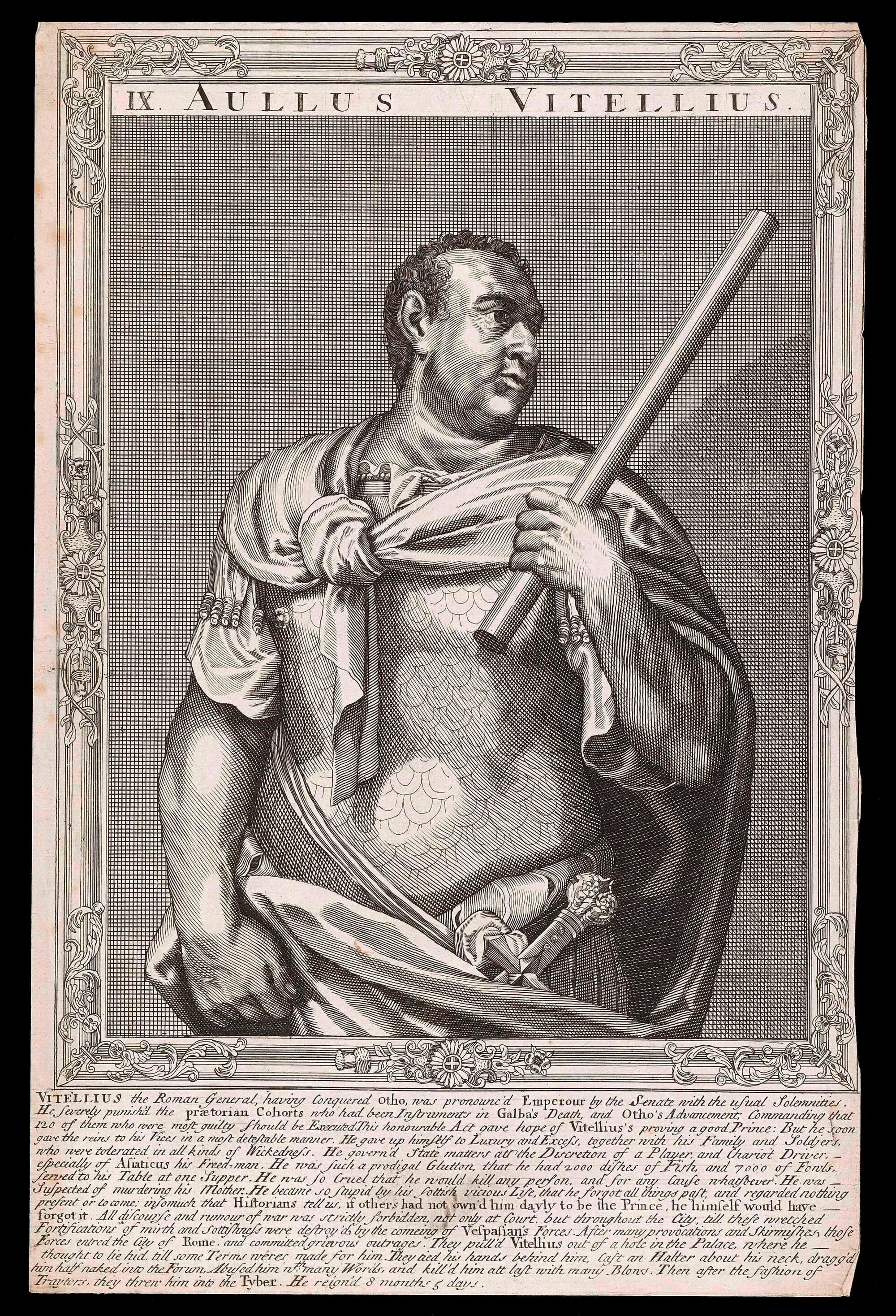

Emperors and moral portraiture: “bad” rulers are frequently described with corpulent markers (Nero, Vitellius, Domitian), while some “good” or moderate emperors are only “a little fat.” The text rightly flags the tension between moralising physiognomy and realistic portraiture – these can overlap rather than cancel each other out.

Comedy’s mixed body of old age: satire and comedy repeatedly pair potbelly with age, even though age is also linked to emaciation. Aristophanes makes the contrast explicit through Poverty:

“With him they are gouty, big-bellied (γαστρώδεις)… with me they are thin (ἰσχνοὶ), wasp-waisted…”(Plutus 559–561)

Notable individuals and self-fashioning: fatness is attached to figures from Aeneas and Aristotle to Aesop and Horace. Suetonius preserves the most quotable vignette – Augustus teasing Horace:

“you seem to me to be afraid that your books may be bigger than you are yourself… it is only stature that you lack, not girth… like that of your own belly”. (Suetonius, De poetis)

Monstrous Bodies and Cruel Spectacle

Late antique biographical fiction, especially the notoriously unreliable Scriptores Historiae Augustae, preserves a disturbing blend of sadistic humour and fascination with bodily excess. In anecdotes about emperors such as Commodus and Heliogabalus, corpulence is treated not as a human condition but as a spectacle – bordering on monstrosity.

Commodus is said to have collected “monstra”: men with artificially induced deformities, hunchbacks, and even

“a fat man (pinguem hominem), whose belly he cut open down the middle, so that his intestines gushed forth.”

The obese body appears here on the same level as physical anomalies deliberately produced for amusement. Whether historically credible or not, the story reveals a cultural logic in which excessive flesh becomes something grotesque, suitable for display or mutilation.

Heliogabalus allegedly staged grotesque banquets by inviting groups defined by bodily peculiarity – bald men, one-eyed men, the gout-ridden, the deaf, and “eight fat men,” whose size made them physically incapable of reclining on a single couch. Laughter is central. Fatness is framed as visual excess, awkward and comic, stripped of dignity.

In these narratives, neither obesity nor emaciation evokes pity. Instead, extreme bodies are treated as curiosities. Yet a different tone emerges in a handful of anecdotes where corpulence becomes a source of self-aware humour or even pride. The story of the fat orator Python of Byzantium and his equally large wife parallels rabbinic tales in which corpulent rabbis deflect mockery with wit. When doubts are cast on their virility, they reply: “as the man, so is the virility.” Corpulence here becomes a rhetorical reversal rather than a stigma.

Another anecdote tells of a “fat young man (νεανίαν … πίονα)” who boasts of his ability to out-eat all others. Called “a glutton (ὁ γαστριζόμενος),” he delights in being stared at and compared to Heracles. Apollonius’ response is cutting:

“There is nothing left for you but to burst, if you want to be stared at.”

The young man’s pride in excess borders on self-exhibition; admiration and grotesque spectacle collapse into one another.

Across these stories, bodily extremes occupy a space between ridicule and wonder. Whether staged by emperors, mocked in literature, or embraced ironically by individuals themselves, fatness – like extreme thinness – could be framed not as pathology but as spectacle: a body that provokes laughter, curiosity, and moral commentary all at once.

Diet, Discipline, and the Medical Management of Weight

From the Hippocratic corpus onward, ancient medicine offered systematic advice for both fatness and thinness. Obesity and emaciation were not moral abstractions alone; they were conditions to be treated through regimen.

For those wishing to lose weight, recommendations included vigorous exercise – walking, jogging, even running in a cloak to induce heavy sweating – along with controlled diet and, at times, induced vomiting. Dry foods were thought especially suitable for “the fat, the effeminate, and persons of cold and humid constitution.” The underlying logic was humoral balance: excess flesh resulted from imbalance, and regimen restored proportion.

Conversely, the slender were instructed to follow the opposite course. To gain weight meant reversing the habits prescribed for the corpulent. Thus, ancient therapy for body size was symmetrical: deficiency and excess were mirror conditions requiring contrary treatments.

Galen advocated a balanced combination of intellectual activity and physical exercise. Ball games in particular promoted a body that was “not too fat, neither too thin,” embodying the ideal of measured proportion. More exotic remedies also circulated. Plutarch reports the belief that dew possessed erosive properties capable of dissolving excess fat; “fat women” were said to soak cloths in dew in hopes of reducing their flesh.

Therapies for extreme thinness (atrophia) are outlined in the Anonymous Parisinus, where restorative walking, warm baths, massage, anointing, breathing exercises, and vocal training were prescribed. Weight gain, like weight loss, required structured bodily management.

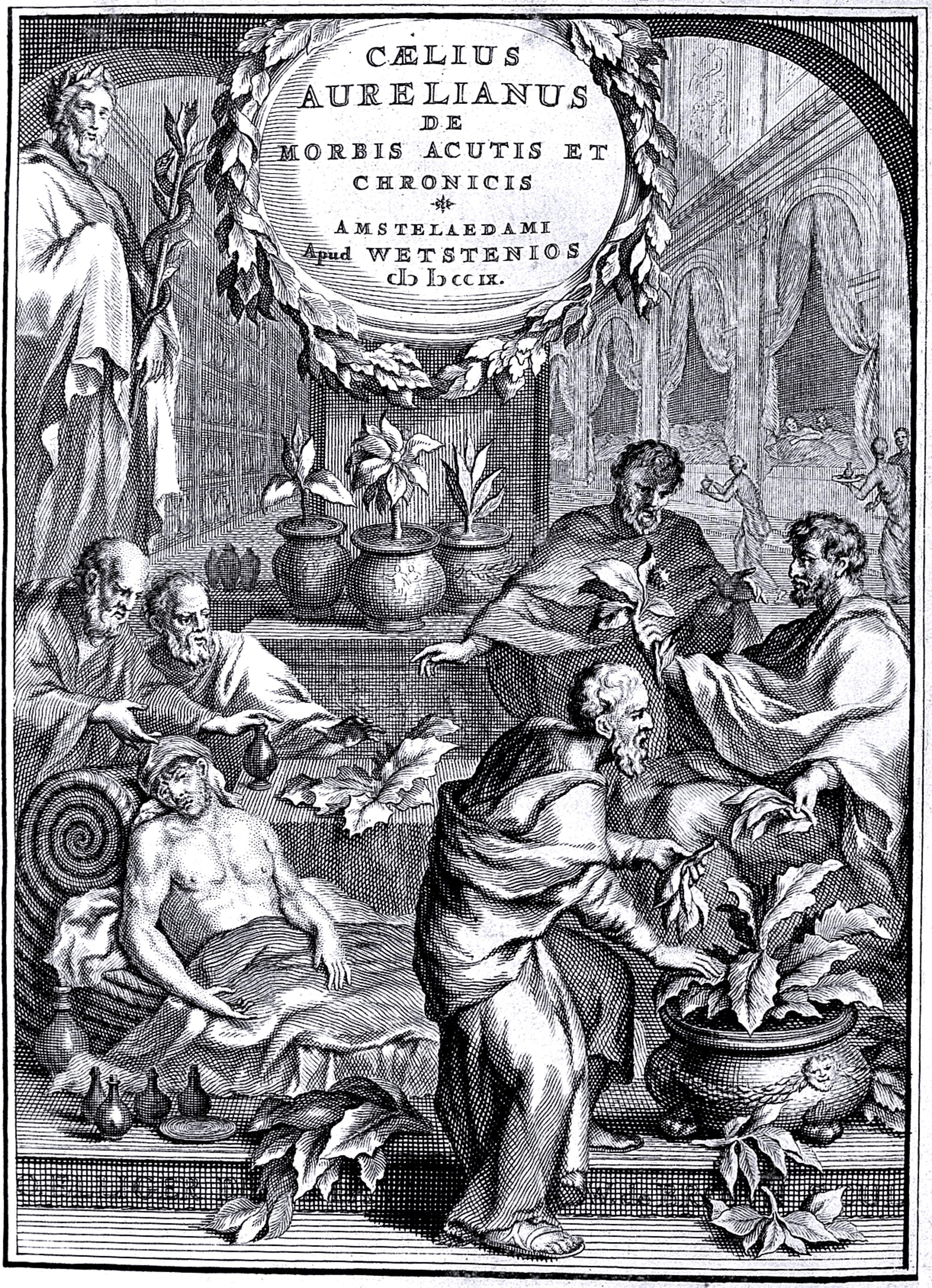

The fullest surviving account appears in the fifth-century physician Caelius Aurelianus. In his Chronic Diseases (Tardarum passionum 3.90–95 on atrophia; 5.129–141 on polysarcia), he synthesised earlier medical traditions and offered detailed therapeutic programs for both emaciation and obesity. His treatments reflect centuries of accumulated medical thought – rational dietetics alongside older popular beliefs, including the supposed dissolving power of dew.

Body, Not Mind: The Absence of Psychological Explanations

Ancient medical writers explained fatness and thinness almost exclusively in physical terms. Even in the key discussions of atrophia and polysarcia, mental states appear only as consequences of bodily imbalance – never as causes. The conditions themselves are grounded in material processes, humoral theory, and regimen. The very idea of a “mental disease” in this context remains foreign to the framework of ancient medicine.

Only one passage approaches what modern readers might consider a psychological dimension. Soranus notes that girls at puberty sometimes grow fatter because they are kept in seclusion, deprived of movement and exercise. Yet even here, the explanation remains environmental and physical rather than emotional; no inner distress or trauma is invoked.

Likewise, bulimia and anorexia never emerged as distinct diagnostic categories. The Anonymus Parisinus explains bulimia – literally “ox-hunger” – through physiological causes alone, and its therapies contain nothing resembling psychological intervention. Terms such as gastrimargia (gluttony) or licheia (compulsive craving for sweets) occur, but they are not medicalised in a modern sense, nor explored as mental disorders.

Cases that modern observers might retrospectively interpret as eating disorders – such as extreme ascetic fasting – were framed differently in antiquity. Ascetic practices were understood as religious and communal acts directed toward God, not as individual psychological conditions. Even when behaviour appears extreme, it was never isolated, named, or theorised as a separate mental pathology.

In short, ancient discourse treated weight as a matter of bodily balance and regimen, not of psyche. The categories through which modern societies interpret eating disorders simply did not exist. (“Writing the story of fatness and thinness in Graeco-Roman antiquity” by Christian Laes)

Across medical treatises, satire, philosophy, political invective, and biography, fatness and thinness functioned as more than physical descriptions. They became shorthand for moral balance or imbalance, strength or softness, self-control or indulgence. Yet the ancient evidence resists simplification.

Corpulence could signal luxury, but also prosperity; thinness could imply weakness, but also discipline. What emerges is not a single ideal body, but a cultural language in which flesh itself carried meaning. In that language, the Roman body stood at the intersection of health, morality, and social identity – visible, interpretable, and never entirely neutral.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: