How was the Roman Empire Formed?

The death of the Roman Republic, gave birth to the Roman Empire; an Empire that left an unparalleled legacy to the Western World.

The Roman Republic did not fall in a single day, nor at the hands of a lone man. It died slowly, battered by civil wars, political ambition, and the weight of its own contradictions. What began as a system built to prevent the rise of a king collapsed under the rule of generals who commanded armies more loyal to them than to the Senate.

The assassins of Julius Caesar believed they were striking a blow for freedom, yet their daggers only hastened the Republic’s demise. In the power vacuum that followed, Rome’s fate was sealed—not by the ideals of the past, but by the will of a single man who would reshape it forever. From the ashes of the Republic, the Empire was born.

Power, Perception, and Political Change

Clifford Ando, in his work “From Republic to Empire”, published in The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World, examines the crucial turning points that led to the transformation of Rome’s political structure, particularly the events of 27 BCE.

At Senate meetings on January 13 and 16 of that year, Octavian, later known as Augustus, formally relinquished the extraordinary powers he had accumulated in the chaotic years following Julius Caesar’s assassination. This act symbolized the end of a century-long crisis of civil wars.

However, the relinquishment was only partial. Augustus retained an array of powers that maintained the outward appearance of republican governance while fundamentally altering the balance of authority. As Augustus himself stated in his Res Gestae:

“In my sixth and seventh consulships, after I had extinguished the civil wars, having through universal consent mastery in all things, I transferred the commonwealth from my power to the discretion of the Senate and People of Rome.

For this good deed I was named Augustus by decree of the Senate…

After this time I excelled all in authority, but I had no more power than the others who were my colleagues in office.”

Despite this claim, Augustus' reign marked the definitive shift from republic to monarchy, a transition that Tacitus highlights in his Annals, emphasizing how the princeps absorbed the functions of the Senate, magistrates, and laws while preserving the traditional offices in name alone. Tacitus notes:

“Under the title of princeps, Augustus took unto himself munia senatus magistratuum legum (the separate powers of the Senate, magistrates, and laws), even as eadem magistratuum vocabula (the titles of magistracies remained the same).”

This shift was widely acknowledged by contemporary Greek observers, who had no hesitation in calling the new system what it was: a monarchy. In contrast, Romans maintained a facade of republican continuity, though the reality was a consolidation of power under Augustus.

The brutality of Augustus' rise to power presented a challenge to his later image as Rome’s stabilizing ruler. He had played a central role in the violent proscriptions of the triumvirate, including the infamous executions at Perusia, which imperial literature later described as ritualistic sacrifices at the altar of Julius Caesar. Tacitus notes that, upon Augustus' death, many Romans accepted that there had been:

“no other remedy for their strife-torn state than that it should be ruled by one.”

For Velleius Paterculus, writing under Tiberius, Augustus’ rule was not about constitutional restoration but about restoring order to a world shattered by civil war:

“The civil wars were ended after twenty years, foreign wars were buried; peace restored; the madness of arms everywhere put to rest.

Strength was returned to the laws; authority to the law courts; dignity to the Senate.”

Ando argues that viewing Augustus' rise as a definitive revolution risks oversimplifying the complexities of Rome’s transition. The republic had long been an imperial power, subjugating Italy and beyond, centuries before Augustus took the throne. He notes that Cicero himself identified the annexation of Sicily in 241 BCE as the beginning of Rome’s imperial ambitions:

“Sicily was the first province to be so named, an ornament, as it were, of empire; Sicily it was who taught our ancestors how outstanding a thing it is to exercise imperial power over a foreign race.”

Thus, Rome had been an imperial state long before it was ruled by emperors. The division of its history into "Republic" and "Empire" obscures the deeper continuity of Rome’s expansionist policies. Ando suggests that the end of the republic was not merely the birth of an empire but rather a consequence of an empire that had outgrown its republican institutions. The influx of wealth and power from foreign conquests, coupled with internal political crises, created tensions that the republican system could no longer contain.

By the early principate, Rome’s government underwent not just a political shift but a deep social transformation. The Augustan age brought legal and administrative reforms that penetrated deeply into provincial life, establishing an unprecedented level of Roman governance. Meanwhile, the old republican framework, though still visible, had lost much of its original meaning.

The creation of res publicae at the local level in the provinces offered a semblance of self-governance, yet it was the emperor who ultimately held control. The failure of the republic was not due to a lack of constitutional adherence but rather to its inability to accommodate the complexities of an expanding empire.

Ultimately, Ando argues, Augustus' rule was both a culmination of Rome’s imperial tendencies and a response to the deep fractures within its society. His principate offered stability, but at the cost of republican ideals—replacing the rule of many with the rule of one.

The Paradox of Rome’s Revolution

Richard Alston, in his book “Rome’s Revolution: Death of the Republic and Birth of the Empire”, explores the complex and paradoxical nature of Rome’s transition from Republic to Empire. He notes that for over two millennia, scholars have debated the roles of Julius Caesar and Augustus, as they stood at the center of this transformation.

Caesar’s legacy has been particularly significant, as his name has become synonymous with a form of authoritarian rule—Caesarism—where strong leaders impose reforms that reshape history. Figures like Napoleon have been linked to this concept, though later authoritarian rulers turned it into a justification for dictatorship.

However, Alston argues that Caesar himself was not the radical reformer many assume. While he was a brilliant military leader who conquered Gaul and emerged victorious in civil wars, he did not institute a lasting political structure. His rule was abruptly ended by assassination, and his policies did not establish a stable government. Instead, it was his heir Octavian, who truly transformed Rome.

Despite Augustus’ immense influence, Alston suggests that he did not necessarily have a grand, premeditated vision for Rome’s future. Rather, he navigated the chaotic political landscape through pragmatic decision-making, responding to immediate challenges rather than pursuing a single ideological goal. While Augustus was undoubtedly an astute politician, his success was partly a result of adaptability rather than a carefully planned revolution.

The collapse of the Republic remains a paradox; for centuries, Rome thrived under republican rule, conquering Italy and much of the Mediterranean.

A Roman Battle, a painting by Simon Peter Tilemann. Public domain

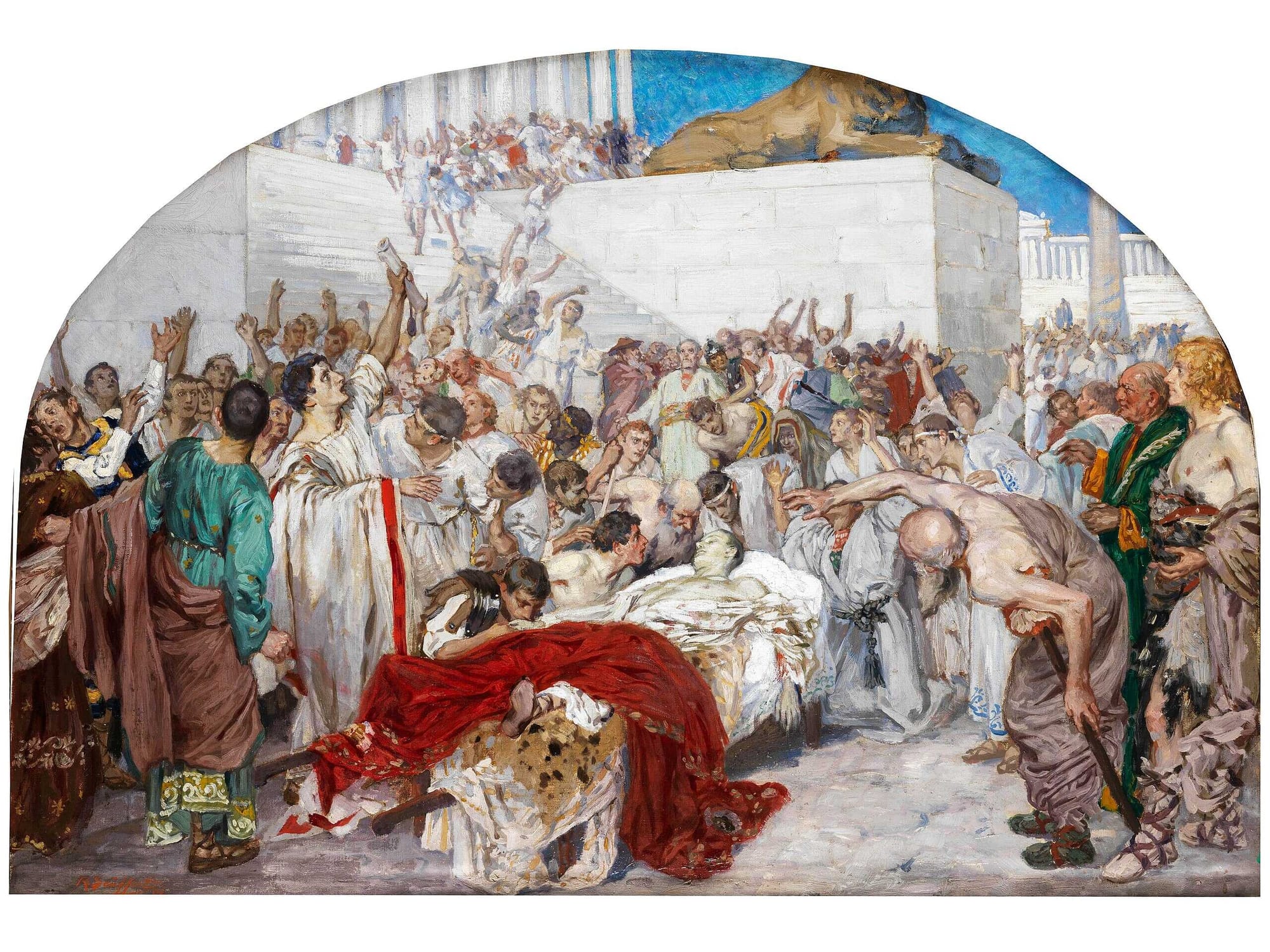

Yet, by the late first century BCE, Romans abandoned this system, embracing the imperial monarchy—despite its seeming incompatibility with their traditional political values. The vast majority of scholars agree that the critical moment in this transformation was the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE. Ironically, those who killed Caesar did so in the name of preserving the Republic, believing him to be a tyrant. Their act, intended as a defense of Roman law and liberty, ultimately set the stage for the very monarchy they sought to prevent.

Marcus Junius Brutus, one of the leading conspirators, had a deeply personal connection to Caesar, as his mother, Servilia, was rumored to have been the dictator’s lover. Rather than supporting Caesar, Brutus sought to emulate his supposed ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, who had overthrown the last Roman king in 509 BCE.

The conspirators expected to be hailed as liberators, but their actions backfired. Instead of restoring the Republic, they were forced into exile and eventually defeated in battle, paving the way for Rome’s transformation into an empire.

Augustus consolidated this shift in 27 BCE, when he formally declared the "restoration" of the Republic while actually establishing a monarchy. Even his final testament to the Roman people, inscribed on bronze pillars outside his mausoleum, emphasized this idea of restoration.

Yet, the reality was starkly different.

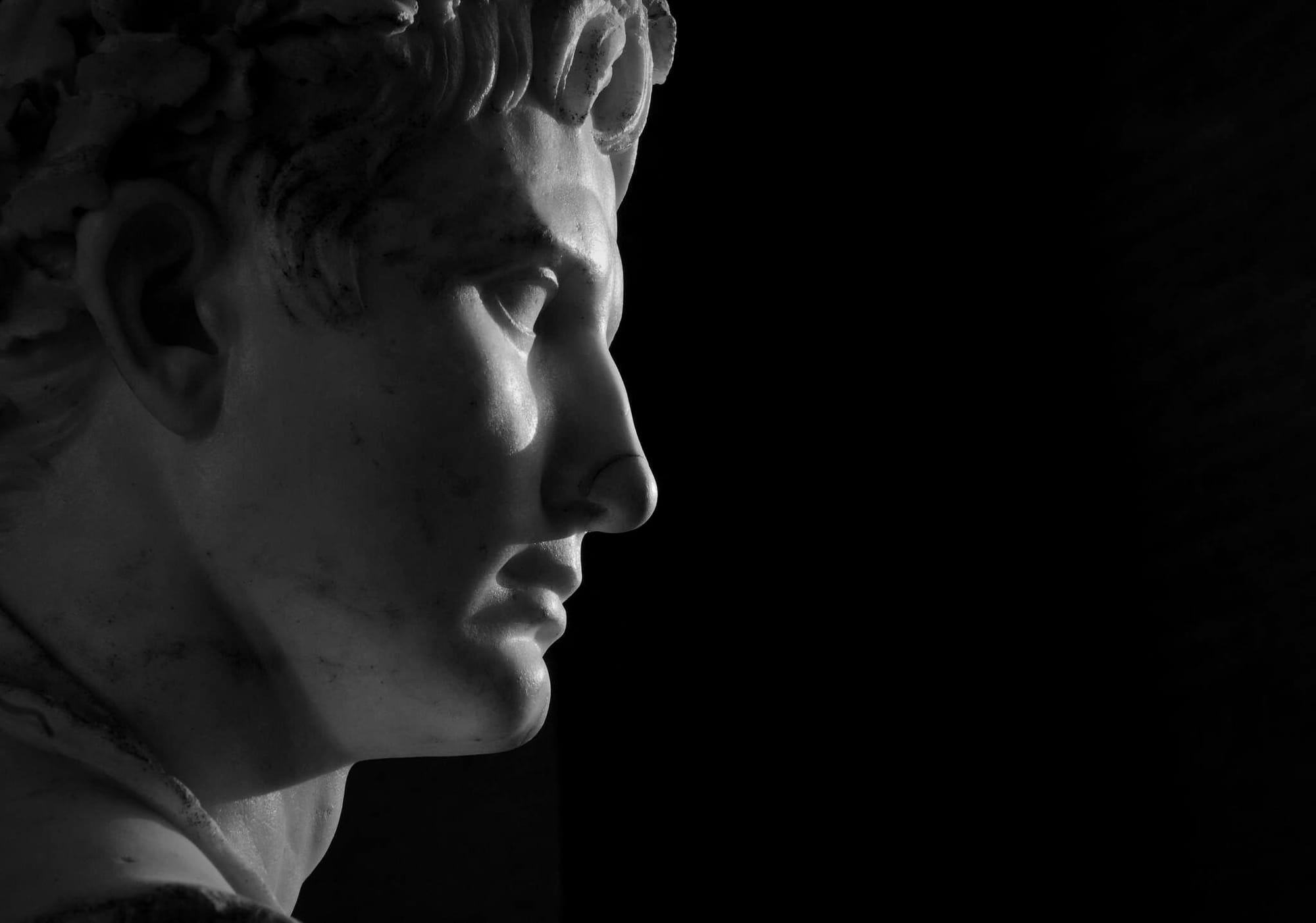

Credits: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The regime maintained the appearance of republican governance, but power was firmly concentrated in Augustus’ hands. His rule marked the beginning of a system that future historians and satirists would recognize as an illusion—an empire disguised as a republic.

Unlike modern revolutions, the Roman transition lacked a clear ideological or social upheaval. There was no overthrow of a monarch, no radical reformation of class structures, and no grand political manifesto. Yet, Alston insists it was still a revolution.

The shift from republic to empire fundamentally altered Rome’s political culture, replacing the power of the traditional elite with a centralized autocracy. This transformation was not immediate but occurred over decades, through war, state-sponsored violence, and the slow realization among Rome’s ruling class that the nature of their government had irreversibly changed.

How did the Roman Republic Maintain their Power

The senators of Rome were deeply rooted in tradition, governing a society where hierarchical structures were reinforced by history and cultural expectations. The Roman elite carried the burden of maintaining these traditions, believing them to be integral to Rome’s identity.

Despite enduring numerous crises over the final century of the Republic, the political system proved resilient. Between 133 and 31 BCE, Rome experienced at least eleven major episodes of civil unrest and conflict, including several full-scale civil wars.

The Republic’s ability to recover was not solely due to its political institutions or reverence for tradition but rather to the deep integration of political and social structures. In Rome, politics was not separate from society; rather, it was embedded within it. This inseparability forces modern scholars to approach Roman politics differently than contemporary political systems.

Rome functioned as a political culture, where social and political hierarchies were indistinguishable from one another. The senators were not just lawmakers—they were also the wealthiest citizens, cultural patrons, religious representatives, judges, and military commanders. Their authority was legitimized by historical precedent and their own successes.

To dismantle senatorial power would mean more than just political reform—it would require a complete restructuring of Roman society. Such a transformation would erase traditions, undermine the social order, and throw the state into chaos. For Romans, a Rome without the Republic was an unthinkable catastrophe—an end to Rome itself.

This deeply ingrained political culture fostered an elite consensus on governance. Rome’s political hierarchies were so tightly interwoven with its economic and social frameworks that, from the elite’s perspective, the system appeared absolute, with no viable alternative. While competition within the aristocracy was fierce, there was no structured opposition to the system itself.

Yet beyond the ruling elite, there existed millions of ordinary Romans whose voices are rarely preserved in historical records. The city of Rome alone had over a million inhabitants, while Italy as a whole was home to more than five million people. It is likely that the lower classes held political views distinct from those of the elite.

While their perspectives remain largely absent from the historical record, it is improbable that they simply accepted the values and beliefs of the ruling class without question. Their experiences and interpretations of Rome’s political transformation were undoubtedly different, even if they remain largely unknown to us today.

Rome’s Revolution: Chaos, Continuity, and the Transformation of Power

Revolutions occur when a dominant ideology collapses, making way for a new political culture. However, revolutions are often chaotic and violent, with the new order forming gradually over time—often retaining elements of the old. After 43 BCE, when Rome fell under the control of the triumvirs, the state was plunged into upheaval. Traditions were abandoned, and between 43 and 32 BCE, every aspect of Roman society was destabilized.

Yet, despite the disorder, a new political system emerged, and Rome endured.

One of the three famous paintings of Antoine Caron, depicting the massacres of the Triumvirate. Public domain

Modern historians tend to downplay the idea of Rome experiencing a true revolution. As aforementioned, the final century of the Republic was marked by assassinations, riots, and civil wars—clear indications of a failing political system.

Yet, there was no specific radical movement advocating for systemic change. While modern scholars identify economic inequality, agrarian crises, and social disparities as key issues of the late Republic, Roman political discourse barely addressed them. Reform efforts focused on restoring lost moral values rather than restructuring the political or economic order.

Ancient sources express deep skepticism about Rome’s ability to recover. Many believed that imperial expansion had eroded the traditional moral and social framework that had once upheld the Republic. A return to earlier values seemed impossible without sacrificing the wealth and dominance Rome had gained through conquest. This paradox was central to the Augustan transformation.

By 14 CE, despite claims of a revolution, much of Rome’s governing class remained unchanged. The aristocracy, largely descended from the old Republican elite, still held power. The Senate continued to function, magistrates were elected, and government institutions remained intact. Some historians have even argued that Augustus merely refined an inefficient system rather than initiating a true revolution.

However, such interpretations overlook the drastic shift in power dynamics. By 40 BCE, Rome’s leadership was entirely different from that of previous generations. The new ruling class had seized power through force, eliminating opposition and rewarding their supporters—particularly the military. Just a few years earlier, senators could insult and dismiss military officers without consequence; by 40 BCE, those same soldiers controlled Italy.

The Senate still existed,

but it no longer ruled Rome.

Credits: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

To fully grasp this transformation, one must abandon conventional frameworks that focus solely on institutions and legal structures. Roman politics was not driven by constitutional change but by shifting networks of power, where alliances and military loyalty determined authority more than traditional senatorial governance. In the end, Rome shifted towards an empire through the lens of history; an empire that some argue, exists in a different form till this day.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: