How did the Roman Army Evolve through the Ages?

The Roman army was not just a military force; it was the backbone of Rome’s rise to dominance and the foundation of its vast empire.

From its humble beginnings as a village on the Tiber River, Rome developed a structured and disciplined army that played a critical role in its rise to power. In its earliest days, the Roman army was a small, loosely organized force composed of the king, his bodyguards, retainers, and local clan groups.

The equipment included oval or circular shields, leather corslets with metal chest protectors, and conical bronze helmets, though concrete evidence of the army's organization remains scarce. Early conflicts were little more than localized skirmishes between small raiding bands.

The early Roman military closely resembled those of neighboring towns in Latium, influenced heavily by the Etruscans, the dominant power in central Italy during the first millennium BCE. Etruscan influence is evident in the names of the three original Roman tribes—Ramnes, Tities, and Luceres—each contributing 1,000 infantry and 100 cavalry to form a legion of 3,000 men and 300 equites (cavalry). This system established the framework for what would become the Roman legio (levy).

The Servian Constitution

Attributed to Servius Tullius, Rome's sixth king (580–530 BCE), the Servian Constitution formalized a military system based on wealth and class. Servius is credited with conducting Rome's first census, organizing the population into "centuries" for both voting and military purposes. Wealthier citizens provided their own arms and armor, creating a system where the financial resources of the state were directly linked to its defense.

Military Classes and Equipment

- Equites: The wealthiest citizens, equipped as cavalry and organized into 18 centuries.

- First Class: Armed with a bronze cuirass, spear, sword, shield, and greaves.

- Second Class: Similar to the first but without a cuirass.

- Third Class: Equipped with a spear, sword, and shield, but no greaves.

- Fourth Class: Armed with a spear and shield only.

- Fifth Class: Used slings or stones.

Men over 46 years old (seniores) were assigned to defend the city, while younger men (iuniores) composed the field army. The poorest citizens (capite censi), without property, were excluded from service.

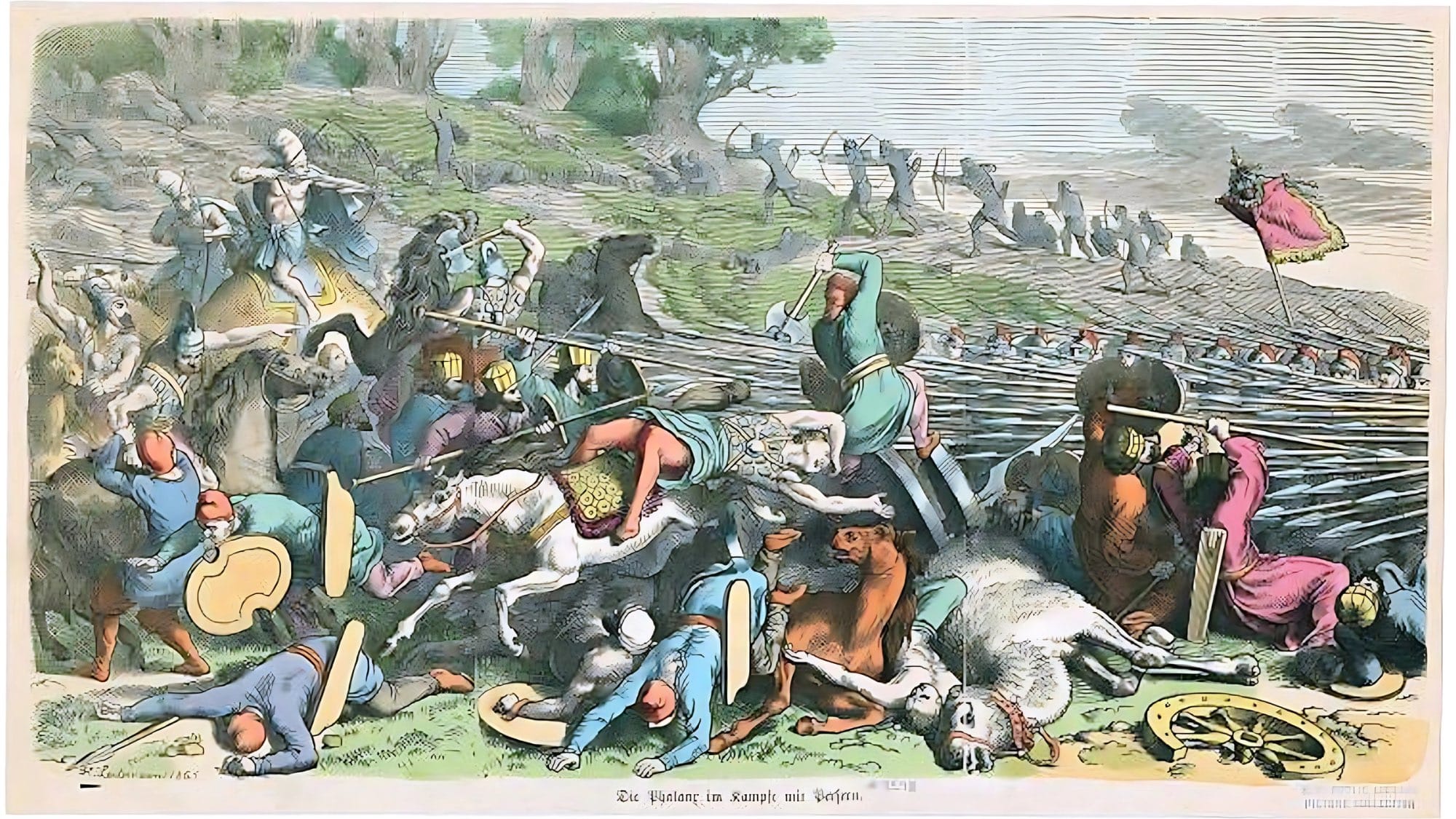

The Servian reforms marked the adoption of a Greek-style hoplite army, with close-order infantry fighting in a phalanx formation. This system, likely influenced by both Etruscan and Greek military traditions, required heavily armed infantry to form tight ranks with overlapping shields and forward-pointing spears. The phalanx, typically eight ranks deep, relied on discipline and cohesion, with replacements stepping forward as casualties occurred. While Roman tradition credits the Etruscans for this military innovation, its roots trace back to Greece, where hoplite warfare flourished during the fifth century BCE.

Some historians question whether the Servian Constitution, with its complex class-based military organization, could have existed as early as the sixth century BCE. It is more plausible that the first stage involved a single classis of citizens who could afford the necessary equipment to serve as hoplites, while those without sufficient property (infra classem) were excluded.

Throughout the Republic, Roman soldiers were drawn exclusively from the citizenry, reflecting a deeply ingrained sense of duty, privilege, and responsibility to defend the state. Early Rome’s military system laid the foundation for the disciplined, professional army that would eventually dominate the Mediterranean world.

The Fall of Veii and Rome's Military Evolution

In the sixth century BCE, the expulsion of the Tarquin kings marked the beginning of the Roman Republic. By the fifth century, Rome had established dominance over Latium through localized conflicts. Simultaneously, the Etruscans, Rome’s powerful northern neighbors, declined under pressure from Greek colonies and advancing Gallic tribes.

Rome’s rivalry with Veii (an ancient Etruscan city and one of Rome’s most formidable early rivals) culminated in a ten-year war, ending with its capture in 396 BCE under M. Furius Camillus. The war prompted significant military reforms, including an expanded army, new equipment like the scutum, and the introduction of soldier stipends (stipendium). However, soon after, the Gallic invasion in 390 BCE led to a devastating Roman defeat at the Battle of the Allia and the sacking of Rome. Camillus again rose to lead Rome’s recovery, driving the Gauls back and preserving the Republic.

These events marked a critical era of military adaptation and resilience for early Rome.

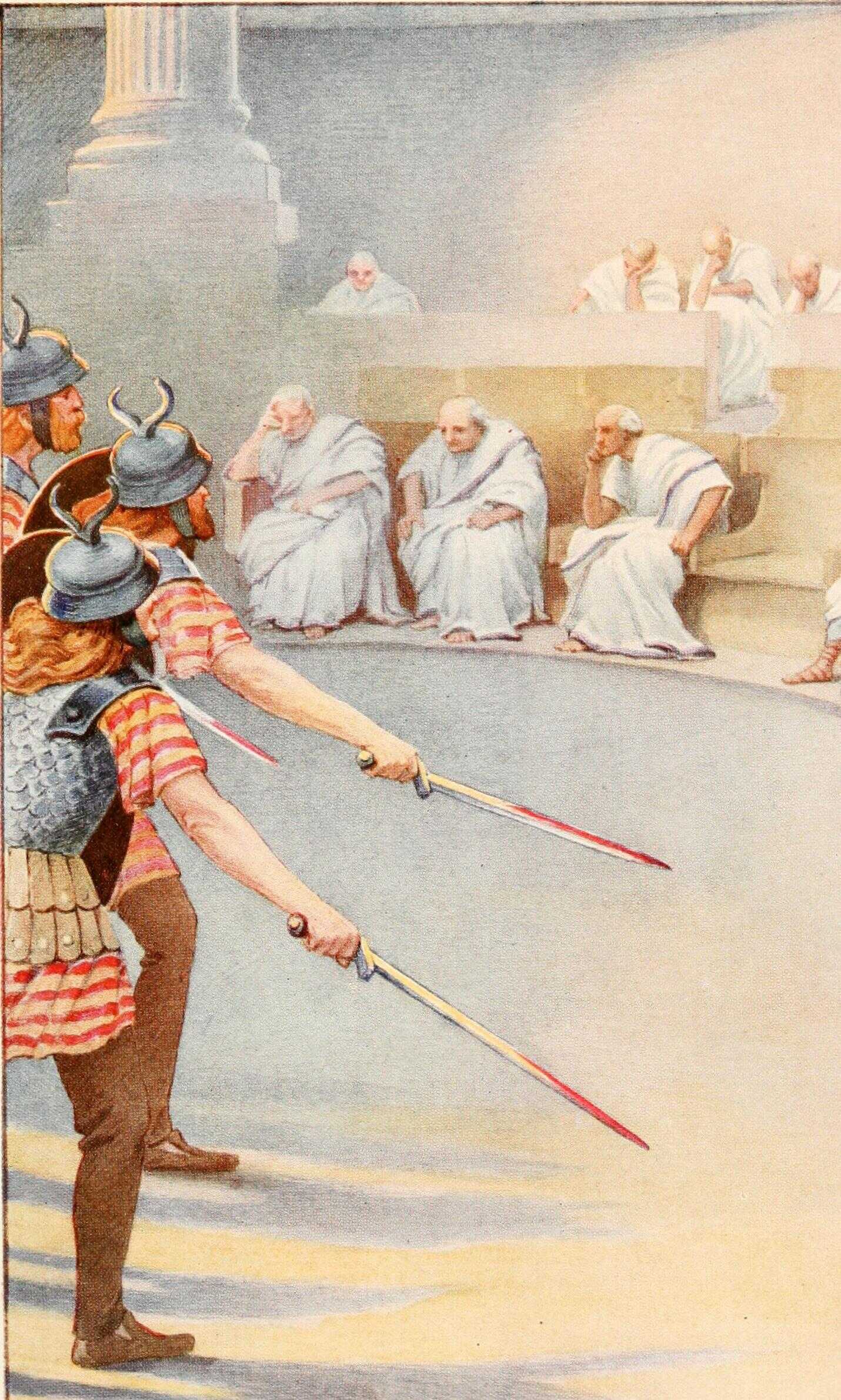

The Gauls entering the Roman Capitol during the Sack of Rome. Public domain

From Phalanx to Legion

The Roman army underwent significant changes in response to weaknesses exposed during the Gallic invasions of the early fourth century BCE. The rigid phalanx formation was replaced by the more flexible maniple system, which allowed smaller units to act independently and adapt to dynamic battlefield conditions.

This period also saw a shift in equipment, with the scutum becoming the standard shield and javelins replacing thrusting spears for most soldiers, enabling more effective ranged attacks before engaging in close combat. These innovations gave the Roman legions an advantage over opponents who maintained outdated phalanx tactics.

By the early fourth century, the army expanded to four legions, each operating as a distinct division under the leadership of consuls or praetors. These reforms marked the beginning of Rome’s transition to a military powerhouse capable of adapting its strategies to conquer the Mediterranean. (The Making of the Roman Army. From Republic to Empire, by Lawrence Keppie)

The Evolution of the Roman Army: Adapting for Victory

The Roman army underwent significant changes in response to weaknesses exposed during the Gallic invasions of the early fourth century BCE. The rigid phalanx formation was replaced by the more flexible maniple system, which allowed smaller units to act independently and adapt to dynamic battlefield conditions.

This period also saw a shift in equipment, with the scutum becoming the standard shield and javelins replacing thrusting spears for most soldiers, enabling more effective ranged attacks before engaging in close combat. These innovations gave the Roman legions an advantage over opponents who maintained outdated phalanx tactics.

By the early fourth century, the army expanded to four legions, each operating as a distinct division under the leadership of consuls or praetors. These reforms marked the beginning of Rome’s transition to a military powerhouse capable of adapting its strategies to conquer the Mediterranean.

From Career Service to Structural Transformation

The Roman army's transition to a standing force was gradual and largely completed by 13 BCE, when Augustus formalized military service terms, marking the beginning of the army as a career. Later reforms, including those under Diocletian in the fourth century, were the result of incremental changes initiated by earlier emperors like Septimius Severus, Gallienus, and Aurelian.

These reforms were not sudden but a culmination of ongoing adjustments over centuries. Traditional methods of analyzing the ranks of the army from a top-down perspective have created misconceptions about earlier structures, projecting later, rigid models backward. A bottom-up approach offers a more accurate picture, reflecting how soldiers experienced career progression in a dynamic and constantly evolving institution.

This gradual evolution underscores the adaptability of the Roman army, which played a central role in the empire’s endurance and transformation.

Photo from a Roman-Barbarian festival, a Roman soldier during the reconstruction of a Roman-Barbarian battle. Credits: Pavel21kriz, CC BY-SA 4.0

The Structure of the Roman Military: Core Units and Adaptations

The Roman military system during the early Empire was structured into three main components:

- Forces Stationed in or Near Rome: This included the Praetorian Guard, equites singulares, urban cohorts, vigiles (fire brigade), and naval fleets at Misenum and Ravenna. These units were under the direct control of the emperor and held a higher status and pay than their provincial counterparts.

- Legions: Comprising about 160,000 men (50% of the total armed forces), the legions were the backbone of the military, stationed primarily along the empire's frontiers. Despite their importance, legionaries were often resentful of the privileges enjoyed by the Praetorian Guard. The legions played a crucial role in conquests such as the invasion of Britain, which required one of the empire’s largest garrisons. Over time, the placement of legions became relatively stable, with some maintaining the same postings for centuries.

- Auxiliary Forces (Auxilia): These units compensated for Rome's traditional deficiencies in cavalry and light-armed troops. Initially recruited from non-citizens (peregrini), auxiliaries were organized into cavalry (alae) and infantry (cohortes), with regiments of 500 or 1,000 men. Over time, auxiliaries became more standardized, and citizenship was often granted upon discharge, blurring the distinction between them and legionaries.

To counteract the loss of distinctiveness in the auxilia, new "irregular" regiments called numeri were created during Trajan and Hadrian’s reigns. These units were raised from less Romanized provinces and fought in their native styles, bringing fresh energy and diversity to the army.

This tripartite system—central forces, frontier legions, and auxiliaries—formed the backbone of Roman military success and adaptability.

The testudo formation displayed in the Roman Army Tactics event in Scarborough Castle. Credits:

David Friel, CC BY 2.0

The Rise and Role of the Praetorian Guard in the Roman Empire

The Praetorian Guard, established as a permanent corps by Augustus in 27 BCE, evolved from earlier Republican-era general bodyguards (cohors praetoria) into a powerful force central to Roman politics and military affairs. Initially consisting of nine cohorts, the guard was stationed in Rome and nearby Italian towns, under the emperor's direct control. By 2 BCE, its command was delegated to two equestrian praefecti praetorio, making the prefecture a prestigious position.

Under Tiberius, Sejanus centralized the Guard into one barracks near the porta Viminalis, consolidating its power in Rome. Subsequent emperors expanded the Guard: Gaius (Caligula) increased its size to twelve cohorts, and Vitellius briefly expanded it to sixteen cohorts, totaling 16,000 soldiers, after replacing the original Guard with troops loyal to him. However, his successor Vespasian restored the Guard to its original nine-cohort structure, later increased to ten by Domitian.

The Guard was predominantly recruited from Italy and Romanized provinces, maintaining its elite status. This policy shifted under Septimius Severus, who replaced the existing Guard after its involvement in auctioning imperial power with soldiers from the loyal Illyrian legions.

Praetorian service offered significant benefits, including higher pay, donatives, and promising career prospects. Veterans could advance to positions such as centurion in the legions or move into high-ranking roles within Rome’s urban forces. Ambitious members who excelled could achieve influential appointments in the Roman administrative hierarchy.

Despite its elite standing, the Guard's history is marked by its political influence and frequent interference in imperial succession. It remained a key force until its disbandment by Constantine in 312 CE, marking the end of its contentious but impactful legacy.

Life in the Roman army demanded unparalleled discipline, unwavering loyalty, and physical endurance. From the dusty roads of provincial marches to the meticulously organized military camps, soldiers adhered to a rigid daily routine that blended training, construction, and combat readiness. Yet, beyond the battlefield, the Roman soldier’s life was also shaped by camaraderie, strict hierarchies, and the relentless demands of expanding and protecting an empire.

The Making of a Roman Soldier: Basic Training and Weapon Mastery

Roman military training was a rigorous process designed to transform recruits into disciplined warriors. Vegetius' De Re Militari, drawing from earlier sources like Cato the Elder and Cornelius Celsus, details the essential phases of this training, emphasizing endurance, precision, and combat skills.

Discipline began with marching—recruits had to cover 20 miles in five hours at standard pace. Vegetius stressed that maintaining formation was crucial to battlefield survival. Physical conditioning included running, jumping, swimming, and carrying heavy loads, all gradually introduced before full armor was added.

Recruits first trained with wooden weapons twice the weight of real ones, practicing thrusting techniques on stakes. This method, borrowed from gladiatorial schools, refined their precision and endurance. Advanced training (armatura) included mock duels, where performance determined rations—failures received barley instead of wheat.

Weapon training in the Roman army was heavily influenced by gladiatorial combat techniques. In 105 BCE, P. Rutilius Rufus introduced gladiatorial instructors into military training, refining soldiers’ ability to anticipate and counter enemy moves.

The final stage focused on the pilum (javelin), with weighted practice versions to build strength and accuracy. Effective use of the pilum was vital, as its design prevented enemies from reusing them in battle.

"At the beginning of their training, the recruits must be taught the military pace. For there is no point which must be watched more carefully on the march or in the field than the preservation of their marching ranks by all the men.

This can only be achieved if by continuous practice they learn to march quickly and in time. For an army that is split and disarranged by stragglers is always in the most serious danger from the enemy."

Vegetius, De Re Militari

To maintain discipline, soldiers who failed to reach proficiency were punished by receiving barley rations instead of wheat. This penalty, though seemingly minor, had a significant impact, as barley was considered an inferior grain and harder to digest than wheat. (The Roman Soldier, by Watson, George Ronald)

A highly dramatized version of Roman military training, likely influenced by historical sources but with fictionalized elements can be enjoyed in the “Frumentarius - Codex I: Spy at the Service of Rome” by Alex Speri. He narrates:

"The weeks that followed have probably been the most physically demanding of my life. Every day, I had to run along the almost sixty stadiums of the Servian Wall and do several hundred squats and push-ups. I was also taught the genus bellator, a kind of obstacle race using specific gestures in order to reduce the need for strength, prioritizing speed and flexibility.

Little by little, with a lot of pain and sweat, I began to master the movements of my habit and learned how to control them. Day or night, we would go out for wild races in the heart of Rome. At the same time, I was taught to climb with the tiger’s paws. The more the weeks went by, the more I appreciated the complexity of my work, the more I saw the determination required to fulfill my duty.

Finally, after six weeks, when I had noticed many physical changes in myself, we began proper combat training. The first few weeks of that phase were painful, and almost every day I ended up in the office of the medicus, who spread antiseptic and healing ointments on me, like olive oil on bread. He also had me swallow powerful analgesic potions so that I could continue with my training.

Every night, as I lay in bed, all my movements were slowed down because of the thousand and one pains I felt. At some point, I even lost count of the number of scratches and bruises that covered my body. At the same time, we began training on the use of weapons. Primus was right: the dragon’s tongue was a real nightmare to master.

Little by little he also taught me everything about assassination tactics and the most suitable techniques for each. About a week before the October Equus feast, Primus announced:

—You are ready! In a week’s time, you’ll take the confirmation test, and if you pass, you’ll become one of us. If you fail, you’ll perish.

—Why should I die?

—We can’t let an ordinary soldier know the Empire’s most secret techniques without being able to control him.

—I understand.

—Take advantage of these last few moments to rest. You really need enough rest before that day. Meet me seven days from now, before dawn by the Castra Prætoria, northeast of the city near Porta Viminalis. Put on your black habit."

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: