Gaius Marius: The Rise and Fall of Rome’s Saviour

From humble Arpinum to seven consulships, Gaius Marius saved Rome from Jugurtha and the northern tribes. Yet his ambition, violence, and rivalry with Sulla turned triumph into terror, leaving a legacy both heroic and destructive.

He was the man who rose from obscurity in Arpinum to dominate Roman politics, the homo novus who shattered precedent with seven consulships and claimed to have saved the Republic from annihilation. Gaius Marius (157–86 BCE) embodied both the promise and peril of Rome’s late Republic: a general who crushed Jugurtha and the northern tribes, yet whose ruthless ambition, political violence, and bitter rivalry with Sulla plunged the state into its first civil war. At once savior and destroyer, his career marked a turning point when military glory became the surest path to power.

The Forgotten Savior of Rome

Since the fall of the Western Empire in 476 CE, the Republic and Empire have held a unique grip on the imagination. Rome’s achievements, longevity, and cultural reach are unmatched in the West. Its collapse, long in the making, now appears inevitable after centuries of strain—yet its influence remains plain to see.

Modern admiration often centers on figures like Caesar, Augustus, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius, and Constantine. But this focus can obscure those who made their rise possible. Among them, Gaius Marius stands out—exceptional in his time, yet comparatively obscure today.

Marius’ ascent was extraordinary. He seized the political stage, stayed in power longer than any Roman before him, reformed the legions, and defeated some of Rome’s most dangerous foes in striking victories. He was hailed as a savior and lauded by the people; at his height, some treated him as more than mortal. For all his flaws, few figures defined their era as decisively as Marius.

He began as an unlikely hero. His family lacked influence; none of his close kin had held office. He professed humble origins and a life marked by hardship, yet he was relentless and ambitious. In an age when wealth and lineage were the usual path to office, he forced his way upward to an influence and popularity unmatched until Julius Caesar—who was linked to him by marriage.

His rise, however, carried costs. Marius increasingly bent constitutional norms when it suited him and worked with dubious allies to achieve political aims. As his power ebbed and rivals pressed him, his harsher traits—pettiness, cruelty, and an unquenched appetite for power—became more visible. In the end, the man who once saved the Republic also helped unbalance it, tarnishing his legacy.

Marius was born around 157 BCE, a time when infant mortality was high and Rome itself was changing fast. Even as Roman power spread, the state showed visible stress. Roman legends of violent beginnings — from Romulus’ fratricide to the fall of kings — set the stage for a Republic wary of one-man rule.

Rome’s rise, like Marius’, was rapid and unforeseen—and it came with risks and side effects.

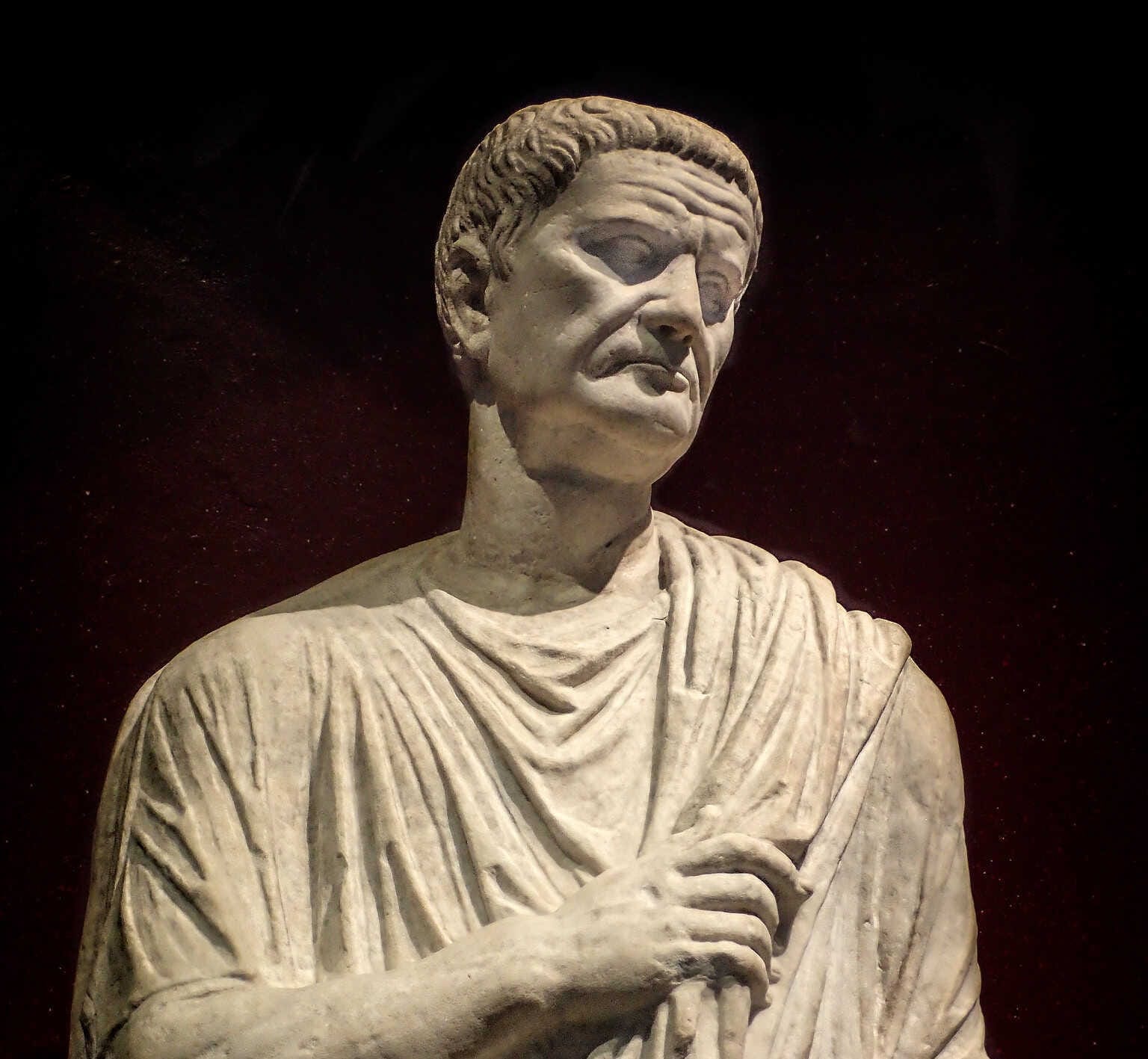

Closeup of a first century CE togate torso bearing a 17th century CE head dubbed Caius Marius. Credits: Mary Harrsch, CC BY 2.0

In 509 BCE, the Romans expelled Tarquinius Superbus and set up a republic, with assemblies, Senate, and magistracies designed to limit power. Through alliances and wars, Rome gained control of Italy. Contact with Carthage led to three Punic Wars. After early victory, Rome endured Hannibal’s long invasion before defeating him at Zama. The memory of that terror—“Hannibal at the gates”—never faded. Later, Cato urged Carthage’s destruction, and Scipio Aemilianus finally razed the city, ending the third war.

By mid-second century BCE, Rome dominated the western Mediterranean, drew wealth from mines, taxes, and booty, and saw slaves and riches flood the city. Yet the capital itself was no marble metropolis—crowded, unsanitary, fire-prone, and haphazardly built. Cicero could call it “Romulus’ cesspool.” Traffic clogged its narrow streets; fires were frequent long before Augustus organized the vigiles.

Politics likewise faltered. Violence grew, demagogues rose, and the system bent. Rome’s society was divided between patricians and plebeians, but wealth and power existed within both. Early plebeian protests—the famous secessions—produced negotiated settlements. Over time, however, the tribunate gained the power to bypass the Senate and take laws directly to the people.

The Gracchi marked a turning point. Tiberius Gracchus pushed land redistribution in 133 BCE, clashed with the Senate, and was killed in street violence. His brother Gaius advanced further reforms, including subsidized grain, and also died in bloodshed. Their program showed the reach of the tribunate—and the growing readiness to use force.

There were no modern parties; candidates leaned on family, reputation, and money. Broadly, populares favored appealing to the people and sometimes bypassing the Senate; optimates defended traditional senatorial authority. Corruption spread—bribes, spectacles, and patronage shaped elections; foreign gifts and domestic payments greased decisions. Both camps shared blame.

Marius spent his youth away from Rome’s grime, at Cereatae near Arpinum, a community long tied to Rome and granted citizenship in 188 BCE. Without that enfranchisement, neither Marius nor Arpinum’s other famed son, Cicero, could have reached Roman office. Rural life was austere and valued; Cato the Elder praised agriculture as the source of Rome’s best soldiers. Marius likely absorbed habits of discipline, frugality, and hard work there.

Little is securely known of his family beyond names—father Gaius Marius, mother Fulcinia, at least one brother (Marcus) and a sister (Maria). Ancient reports differ on their means. Some portray real poverty; others suspect Marius emphasized humble origins to court popular favor. Many modern scholars judge his father to have been an equestrian, which would fit the wealth needed for legionary eligibility in that era.

Education mirrored means. Rome had no public schools; families paid for tutors or group instruction when they could. Greek influence on education was strong, even if some Romans—Marius included, according to hostile reports—dismissed it. In practice, a successful political career implies at least some training in letters and rhetoric, whether formal or self-taught.

Like other Roman youths, Marius likely marked his passage to manhood by donning the toga virilis and being presented in the forum. He came of age as Rome grew richer and wider in reach—but also as its politics coarsened. Beneath Rome’s successes, character failed; that moral decay would shape the world Marius entered—and the one he helped to make.

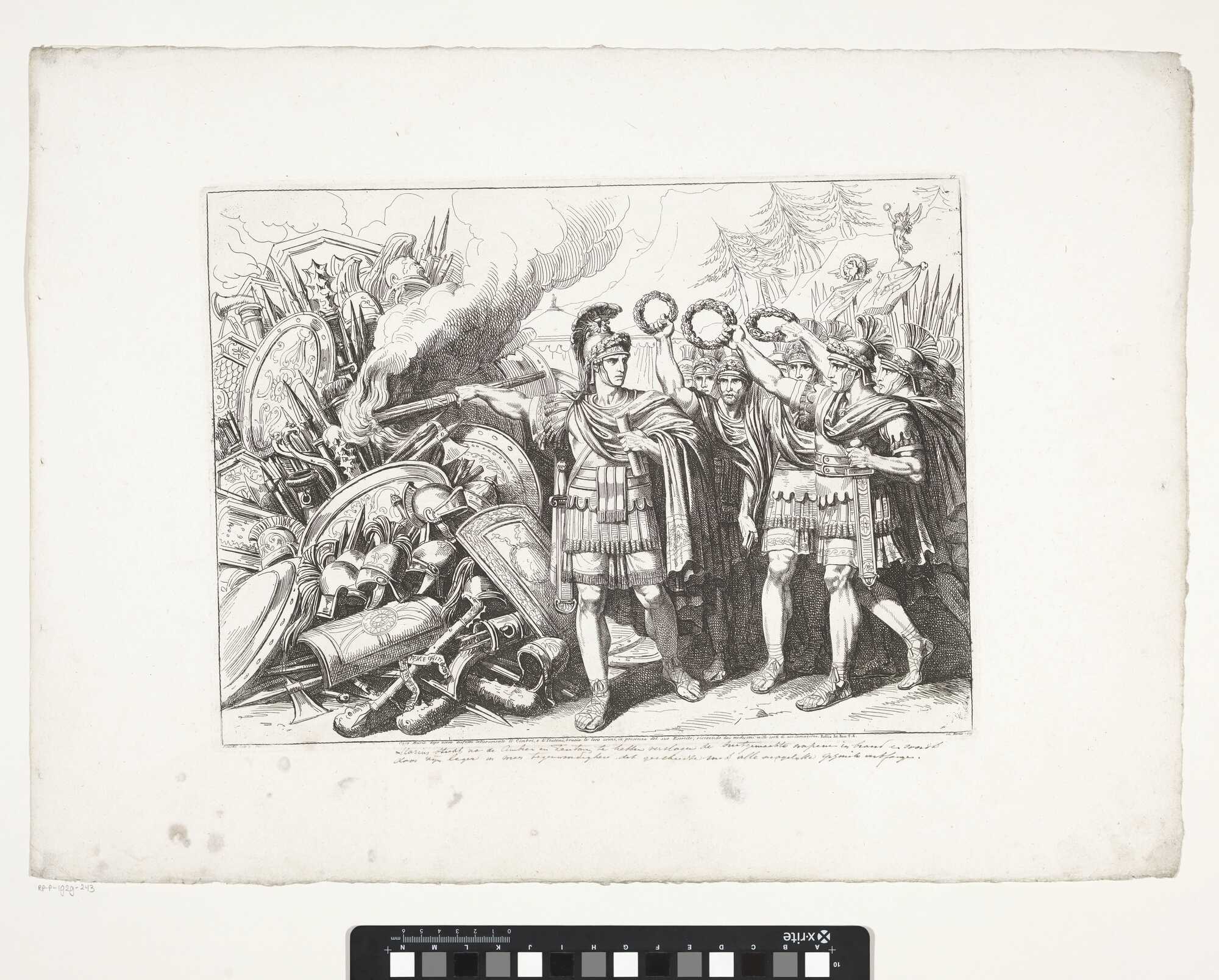

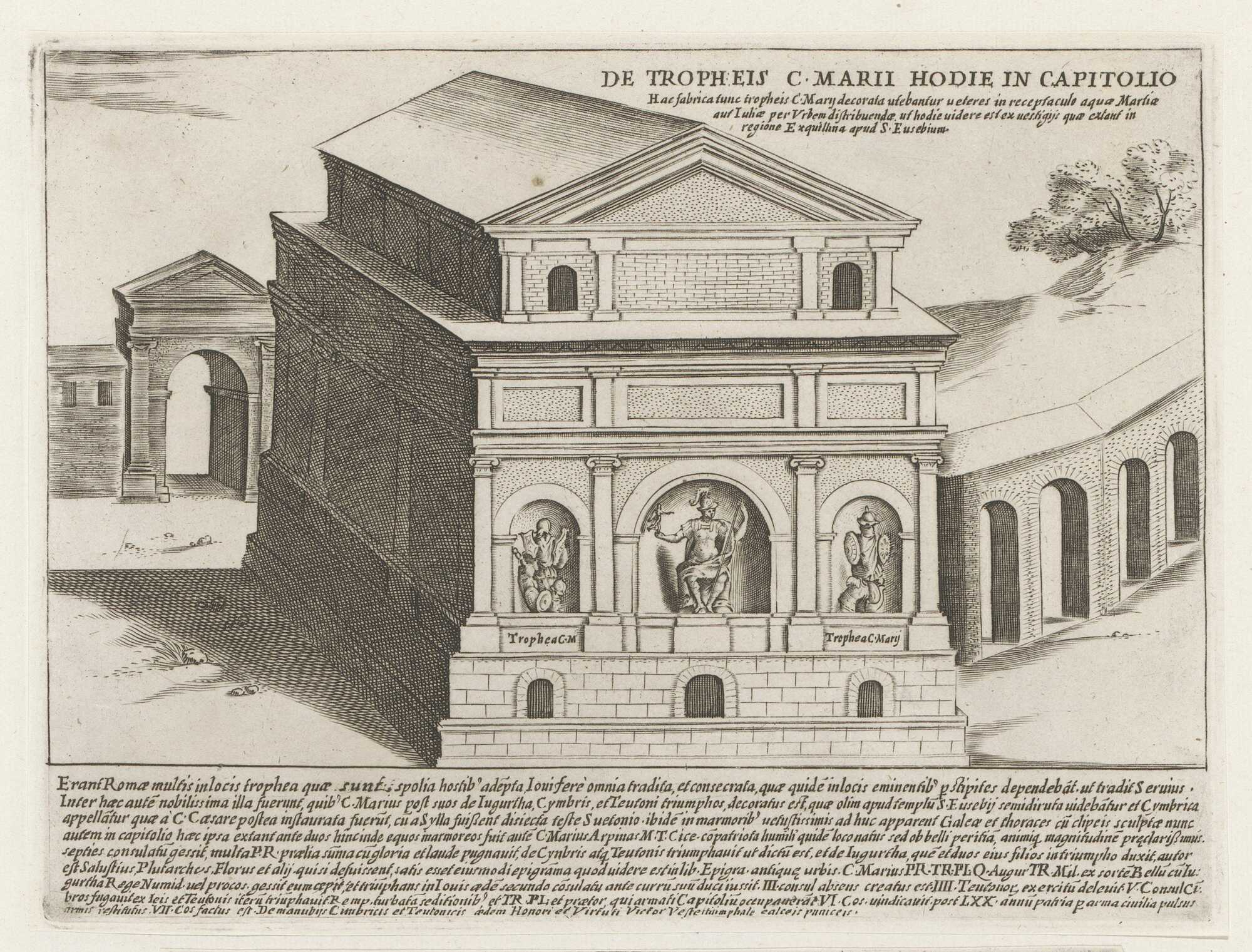

Image #1: Caius Marius after having completely defeated the Cimbri and the Teutons, burns their weapons, in the presence of his Army, receiving from the same thousand lots of acclamations. Image #2: Caius Marius, while he was hiding inside a swamp is discovered by his enemies who were looking for him, and take him out with ropes in order to lead him to Minturna, to decide his fate. Public domain

Numantia: The Making of a Soldier

In the 130s BCE, young Gaius Marius first appeared in the historical record as a soldier in the Third Celtiberian War, better known as the Numantine War. The Romans struggled against the Numantines, who were skilled in guerrilla tactics and defended their stronghold with natural bluffs, walls, and marshes. Several Roman commanders failed, and Rome’s prestige suffered.

In 134 BCE, command went to Scipio Aemilianus, conqueror of Carthage, who restored discipline by harsh training and strict inspections. Marius, possibly serving as a junior officer or cavalryman, impressed Aemilianus with his diligence, courage, and even the care he showed for his horse and mule. According to reports, Marius fought bravely in single combat before his general’s eyes, earning high praise.

Aemilianus encircled Numantia, constructing walls, towers, trenches, and even flooding a swamp to trap the city. As starvation and disease set in, some inhabitants turned to cannibalism. Eventually, many Numantines killed their families and themselves rather than surrender. The survivors set fire to their city before capitulating in 133 BCE, and Aemilianus leveled Numantia as he had Carthage.

Marius’ exact role remains unclear, but his conduct during the campaign won him honors and the notice of Aemilianus, who allegedly patted him on the shoulder and remarked that here was perhaps Rome’s future general. The campaign forged Marius’ ideals of discipline, endurance, and ruthless determination—qualities that shaped his later career.

The Climb Through the Cursus Honorum

Marius’ political career unfolded along the cursus honorum—Rome’s traditional ladder of offices. The Republic’s system divided authority among magistrates and assemblies, limiting individual dominance. Advancement through the ranks demanded both ability and connections.

The path usually began with the quaestorship, focused on financial duties, then moved to the aedileship, where ambitious men won popularity by sponsoring games. The praetorship followed, providing judicial authority and military commands. At the summit stood the consulship, Rome’s highest office, with sweeping military and civic powers.

Other posts added complexity. The tribunate of the plebs, originally created to defend ordinary Romans, had by Marius’ day become a powerful office with the ability to propose laws directly and veto decisions—even those of fellow tribunes. Charismatic tribunes could block senatorial authority, making the office a potent tool of populist politics.

Marius, as a novus homo (“new man”), faced daunting barriers—no aristocratic lineage, no family precedent in high office. Yet with ambition, military distinction, and the backing of patrons like the Metelli, he began ascending the ladder, starting with a military tribuneship and, by 119 BCE, election as tribune of the plebs . His career path, though fraught with opposition, showed that even an outsider could climb Rome’s political hierarchy with persistence, fortune, and skill.

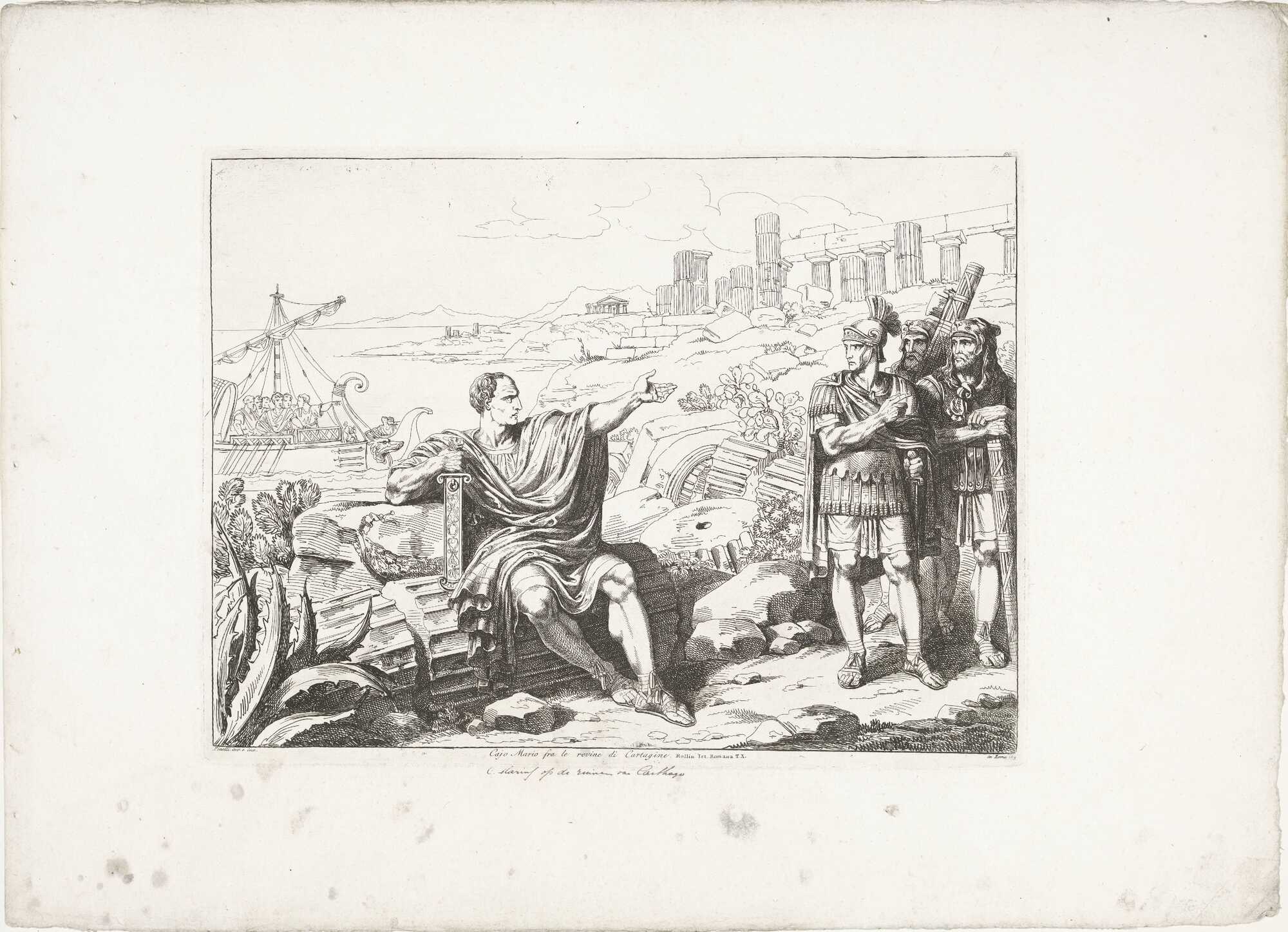

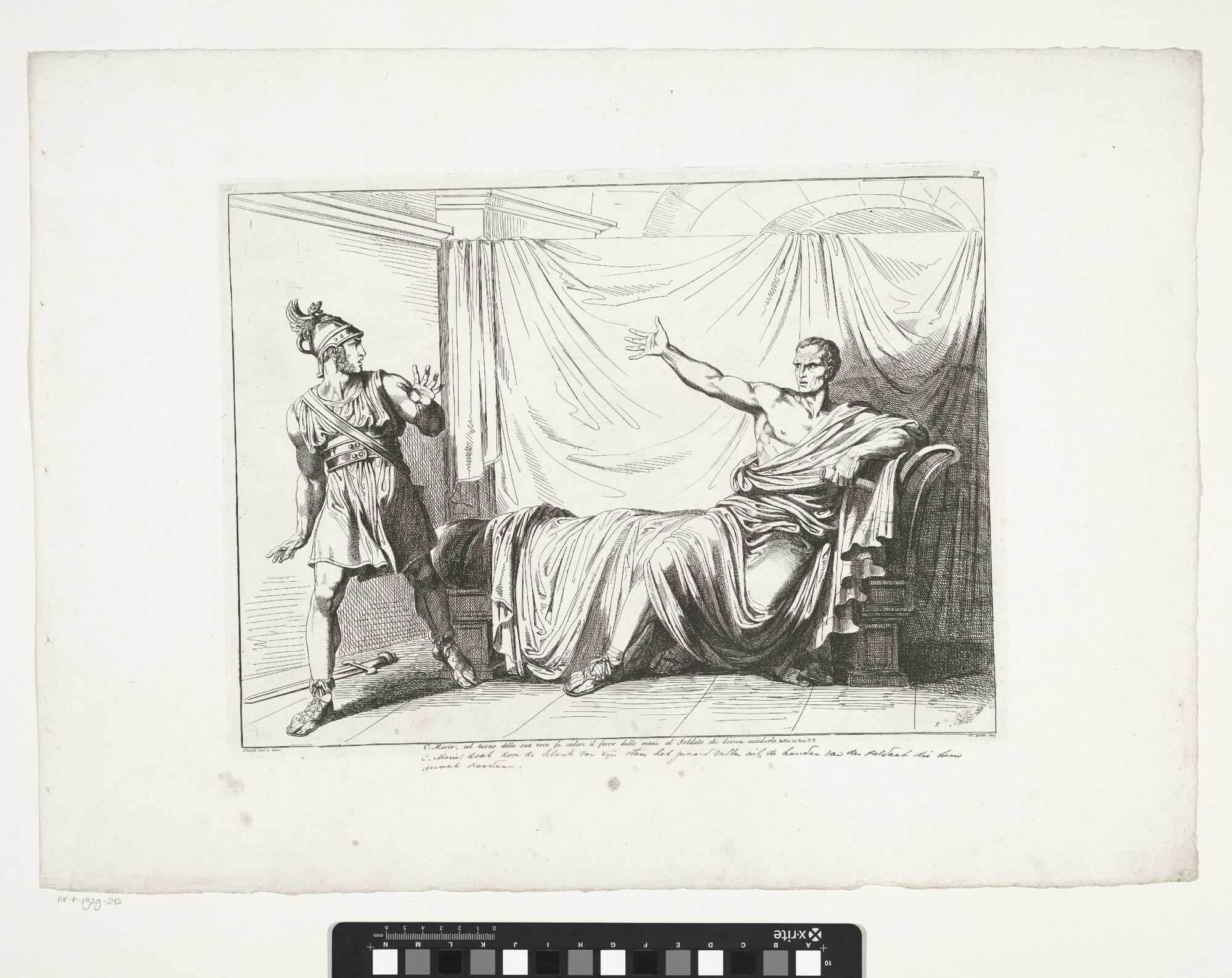

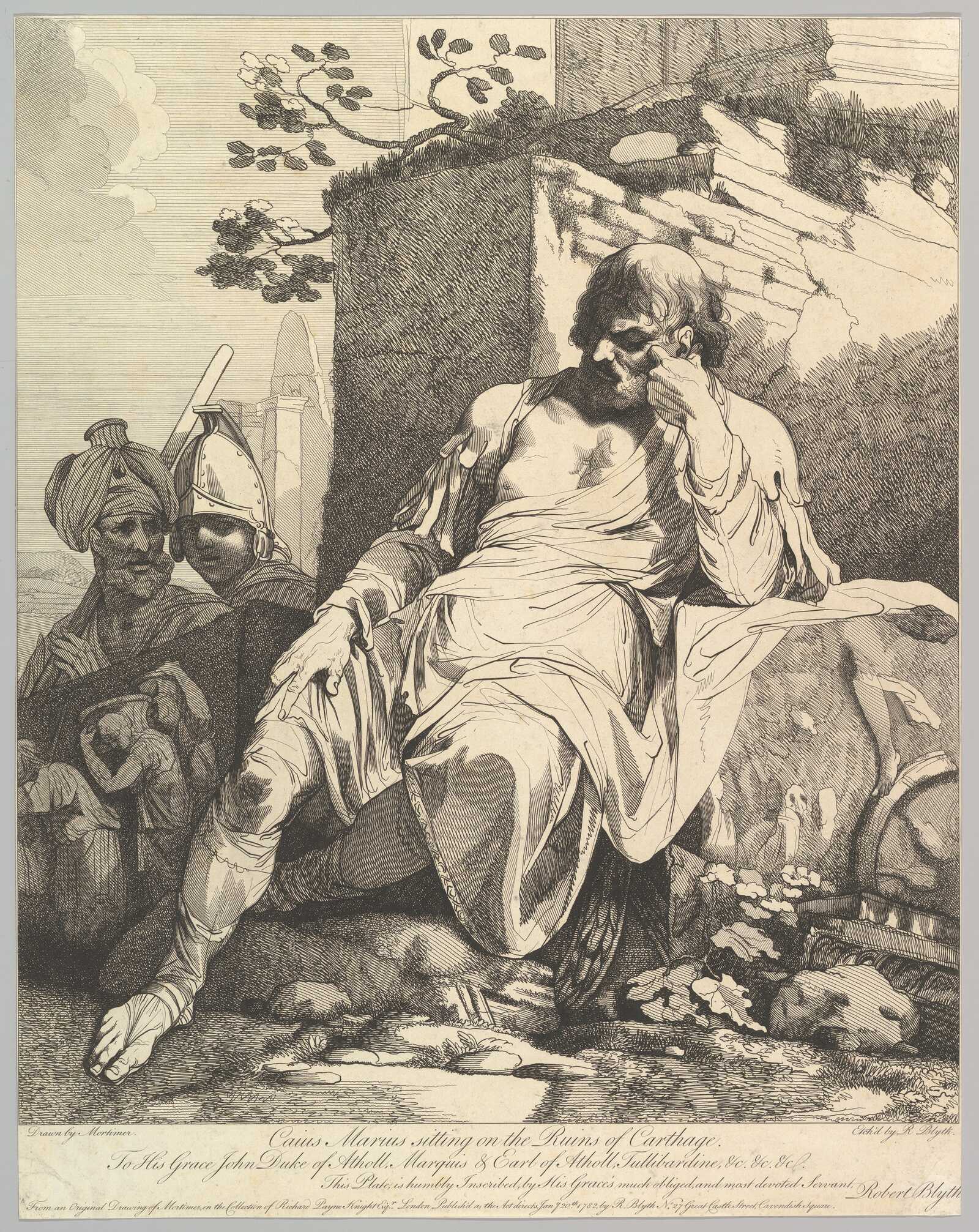

Image #1: Gaius Marius sits on the ruins of Carthage. Image #2: Caius Marius, with the thunder of his voice, drops the sword from the hands of the soldier who was sent to kill him. Public domain

A New Man’s Boast: Scars Instead of Statues

Marius built his career without ancestral portraits to parade in the forum. Instead, he declared:

“I cannot… display family portraits… but I can show spears, standards, cups, and other spoils… and scars on my breast”.

“Ego hominem novi generis, qui non imagines, neque triumphos, neque consulatus maiorum meorum, sed ea quae ipse gessi, virtute parta, habeo.”

“I, a man of new family, have no ancestral portraits, triumphs, or consulships to display, but I can show the spoils I myself have won by valor.”

Jugurthine War, 85.29

This carefully crafted image of the hard soldier appealed to Rome’s masses, who saw in him both simplicity and valor. Still, beneath the rustic mask could lay an insatiable drive: ambition, cunning, and the will to break precedent.

As a youth, Marius was said to have caught an eagle’s nest with seven fledglings—interpreted as an omen of seven consulships, an unheard-of destiny. Whether legend or truth, the story followed him all his life, proof to admirers that fortune had marked him out. Born in Arpinum, likely to an equestrian household rather than the poverty he claimed, he wore austerity as a badge of honor. Later, however, he abandoned that simplicity; Plutarch sneered that his Misenum villa was furnished “effeminately and luxuriously,” a far cry from his farmer’s origins.

Julia of the Julii: Marriage and Alliance

His marriage to Julia of the Julian clan linked Marius to Rome’s nobility, making him uncle by marriage to Julius Caesar. It was a union of ambition and lineage, bridging new wealth with ancient pedigree. Little is known of their personal affection, but politically it was invaluable. They had a son, Gaius Marius the Younger, though some sources suggest adoption.

Shadows of Glory: Rivalry and Resentment

The rivalry with Lucius Cornelius Sulla exposed Marius’ darkest traits. When Bocchus of Mauretania erected a monument in Rome showing Jugurtha’s surrender to Sulla, Marius raged—his glory stolen in stone. The insult festered into hatred. Later, when Sulla secured the Mithridatic command, Marius’ envy was unrestrained. We can descibe him as a man who, having tasted adulation, could not abide being eclipsed.

His ambition grew reckless. Sallust recounts Marius’ claim that noble birth mattered less than personal valor, yet in practice, he would wield violence and intimidation to secure power. Hyden underlines that he was “a soldier first, a politician second,” and when politics failed him, he turned to force.

The Weight of Years: Wealth, Age, and Decline

By his sixties, Marius was fabulously wealthy but plagued by age and illness. To prove his vitality, he reportedly exercised on the Campus Martius in full armor, only to collapse from fatigue. He endured a brutal operation for varicose veins without flinching—stoic to the point of vanity, refusing anesthetic so that no one could call him soft.

His final return to Rome, alongside Cinna, was marked by terror. Declared hostis (enemy of the state), he exacted vengeance in bloody purges, condemning senators and equestrians alike without trial. Once savior, he became scourge, his name tied to massacre as much as to victory.

Between Savior and Destroyer

At his zenith, Marius was adored, hailed almost as a demi-god who had crushed Jugurtha, the Teutones, and the Cimbri. But his fall was spectacular. His ambition, cruelty, and taste for violence corroded his legacy. He had given Rome the army it needed to defend itself, but also the precedent for generals to wield legions as tools of personal power.

The Seventh Consulship and Death

In 86 BCE, Marius returned to Rome in triumph and terror, elected to his seventh consulship—an honor no Roman before him had achieved. Yet his victory was short-lived. Seized by illness and exhaustion, he died only seventeen days into office, at the age of seventy. His death spared him from facing Sulla’s vengeance, but not from history’s judgment.

Rome gave him a grand funeral, complete with honors befitting a savior. The crowds remembered the general who had saved them from Jugurtha and the northern tribes. Yet even in death, his image was divided: to some, the protector of Rome; to others, the man who had set it on the path of civil war. His body lay in state, draped with symbols of victory, but his legacy lingered as both a warning and a memory of greatness undone. (Gaius Marius. The rise and fall of Rome’s saviour, by Marc Hyden)

Marius’ life traced the arc of the Republic itself—rising from obscurity to unmatched power, reshaping Rome in war, and then unraveling in violence and rivalry. His seven consulships secured his place in history, yet his relentless ambition left scars on the state he claimed to save. To remember Marius is to confront both the heights of Roman greatness and the flaws that hastened its fall.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: