Flamma: The Gladiator who Refused his Freedom Four Times

A Syrian-born gladiator who could have walked free but chose the arena instead. Flamma, offered his liberty four times, defied freedom itself to win eternal glory beneath Rome’s roaring crowds.

Among the countless men who bled for Rome’s amusement, few left a mark like Flamma. A Syrian-born secutor, he fought more than thirty times in the arena and was crowned victor in most of them. Yet what made him legendary was not only his skill with the sword, but his defiance of freedom itself.

Awarded the rudis—the wooden gladius sword symbolizing release from gladiatorial servitude—four times, Flamma refused it every single time. His epitaph, carved in stone, remains one of the most haunting glimpses into the gladiator’s world: a man who could walk away, but chose instead to fight until death.

Daniel P. Mannix and the Legacy of Those About to Die

Daniel Pratt Mannix IV (1911–1997) was a man of many lives — writer, journalist, photographer, magician, animal trainer, and filmmaker. In 1958, he published Those About to Die, a vivid and often brutal reconstruction of Rome’s arenas, later reissued as The Way of the Gladiator.

Though written as popular history, the book drew on authentic sources to capture the spectacle, danger, and psychology of the games with striking immediacy. Its cinematic detail proved enduring: the work inspired Ridley Scott’s 2000 film Gladiator and, decades later, the television drama Those About to Die. Through Those About to Die, Mannix shaped how modern audiences imagine the Roman arena—its blood, its grandeur, and the fatal courage of men like Flamma.

The Birth of the Games

In Rome’s earliest days, public competitions were limited to athletic displays. Gladiatorial combat did not yet exist. According to tradition, the introduction of gladiators occurred almost by accident.

Two patrician brothers, Marcus and Decimus Brutus, sought to honor their deceased father with an extraordinary funeral. Lavish processions and sacrifices were not enough to display their devotion, so Marcus recalled an ancient custom —a ritual combat at the grave of great leaders— and proposed reviving it.

“There was an old custom, dating back to prehistoric times, of having a few slaves fight to the death over the grave of some great leader,”

he reminded his brother.

“Why not revive it to show how much we revere the memory of the old man?”

The practice had once been a form of human sacrifice, ensuring that the spirits of the slain would accompany the dead into the afterlife. Over time, it became a test of courage and a public spectacle. Though the Brutus brothers no longer believed in the old superstition, they recognized that such a display would please the crowd and elevate their social standing.

The priests offered no objection, and half of Rome gathered to watch three pairs of slaves fight to the death. The event’s popularity spread rapidly — within a century, games had grown from three pairs in 264 B.C. to ninety pairs fighting for three days by 145 B.C.

Soon, no ambitious politician could hope for election without sponsoring such shows.

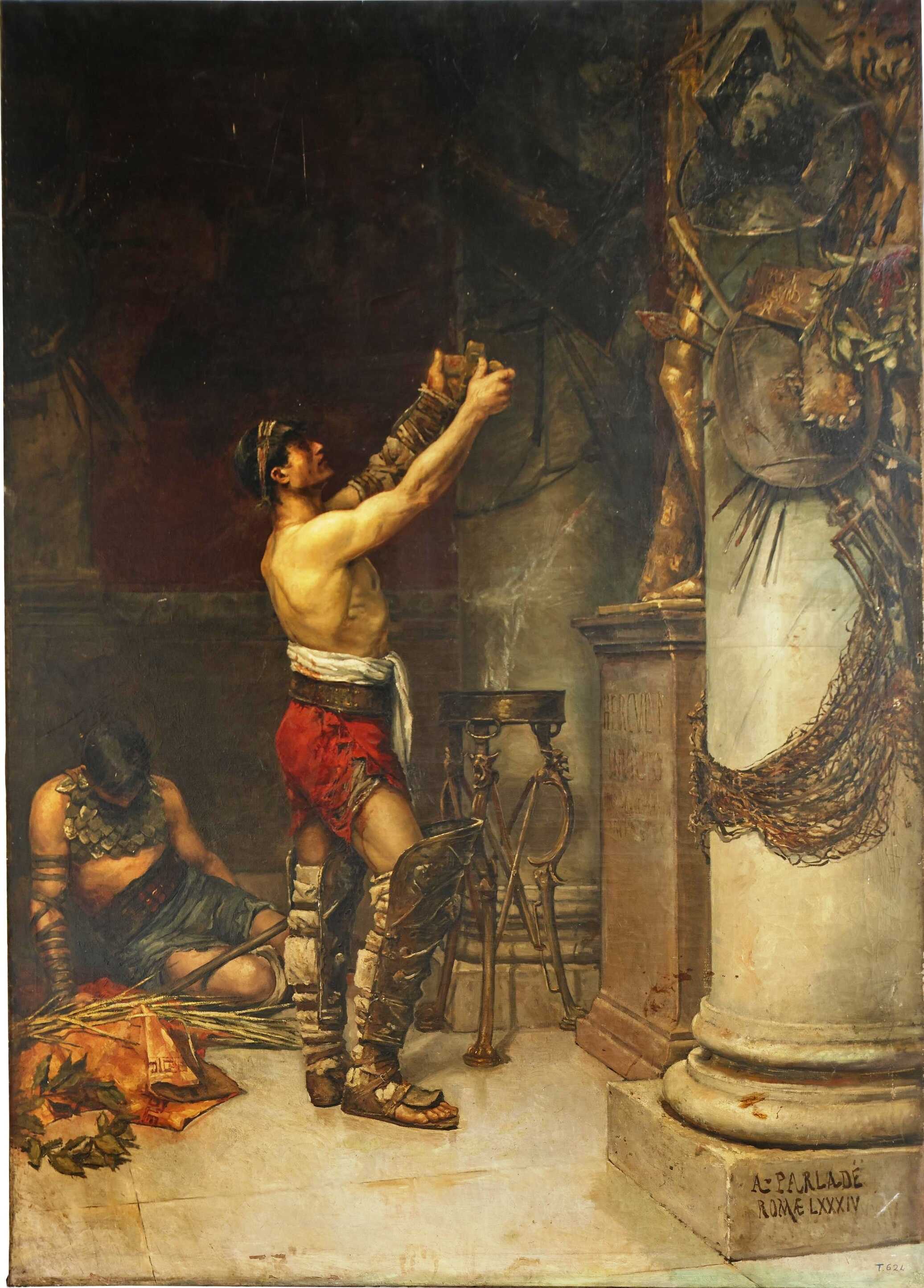

A detail from a mosaic depicting two gladiators in combat, from the House of the Gladiators in Kourion, Cyprus. Credits: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0

Promoters began purchasing able-bodied slaves and prisoners of war, hiring them out as fighters. These professional combatants became known as gladiators, from gladius, the Latin word for sword.

As the spectacles expanded, the venue shifted from the Forum to the Circus, where gladiatorial bouts joined the chariot races and wild animal hunts. Wealthy patrons sponsored them for prestige, while later emperors used them to placate the restless populace.

Although no gladiator ever left behind a personal record — or if one ever did, it has long been lost — much can still be learned from Roman writers who described the games in remarkable detail, including Suetonius, Martial, and Tacitus. Among these half-forgotten names, one rose above the rest — Flamma, the Syrian-born gladiator whose courage and defiance of freedom made him legendary.

Flamma’s Rise and Life in the Arena

Flamma must have been a burly, strong-willed soldier, condemned to the arena for striking a superior officer. The young officer had insulted him; Flamma retaliated, knocking him down, and was sentenced to die in the games.

Expecting to fight another soldier, he was instead pitted against a retiarius, a lightly armed opponent armed with a trident and net. The crowd mocked him as a mutineer unworthy of mercy, but when Flamma’s old regiment appeared in the stands shouting for him, he regained his spirit.

“All right, boys,” he cried, “I’ll do my best for the honor of the regiment!”

The battle that followed was fierce and clumsy — the retiarius blinded him in one eye with a lead pellet, disarmed him, and nearly won, until Flamma seized his chance, kicked the trident across the arena, and with a blow from his shield, killed his adversary. The crowd demanded his life spared, amused that the bearded “loach” — as his comrades called him — had slain a “fisherman.”

Spared by popular demand, Flamma was sent to train in one of the great gladiatorial schools of Italy, likely the one in Rome under Augustus Caesar. There he entered a disciplined world of confinement and skill. Each gladiator had a small cell, and the ludus included kitchens, armories, hospitals, and even a graveyard. The Pompeian school’s remains reveal prisons fitted with shackles and branding irons. New recruits swore an oath:

“to suffer myself to be whipped with rods, burned with fire or killed with steel if I disobey.”

Flamma’s routine was harsh but ordered. He trained against wooden poles, practiced ambidexterity, and sparred with blunted weapons before entering real combat. Meals were heavy in barley and meat, a diet believed to fortify and thicken the blood to reduce fatal bleeding. Over time, he adapted to his new life.

Flamma’s Rewards from the Arena

Fine armor was a trophy awarded for skill. Flamma’s helmets bore ostrich or peacock feathers; his breastplate was inlaid with gold and silver, his shield painted crimson within and adorned with brass studs.

His first professional appearance came at a privately sponsored spectacle advertised across Rome’s walls and tombs. At such events, the crowd roared greetings to the emperor —“Hail, Caesar! We who are about to die greet thee!”— before the fighters marched through the Porta Libitinensis into the arena.

In one early match, Flamma faced German prisoners of war, outnumbered but victorious. He fought methodically, like a soldier executing orders, while the crowd’s attention was seized by another dramatic duel — a Norseman battling a Roman officer. Afterward, Flamma’s calm discipline impressed his trainer, who saw in him a dependable, unflinching fighter rather than a showman.

As his career advanced, Flamma faced opponents of every type — Hoplomachi, Dimachaeri, Andabatae — and consistently survived. Though beaten occasionally, he was saved by the crowd’s “thumbs up,” the traditional gesture of mercy. The exact meaning of these gestures remains uncertain; some believed the “thumbs down” condemned a man, while others claimed it was a stabbing motion signaling death. Whatever the case, Flamma’s courage earned the favor of the spectators.

He never exaggerated his fights for attention, unlike others who staged performances with rehearsed heroics. Still, by his constancy and strength, he became a favorite of Rome. Statues bore his likeness; coins showed him as Mars, and walls were scrawled with the phrases:

“Flamma is a girl’s sigh and prayer.”

“Oh you Flamma! You’re the doctor who can cure what’s wrong with me.”

With fame came wealth. After each victory, sponsors presented bowls of gold coins. Flamma’s reputation allowed him to sell tips on upcoming fights, accurately predicting which men might survive. Yet even at the height of his success, he remained bound to the arena.

Gladiators fought for three years before earning the right to rest, and after five more years of service could be granted a wooden sword, the rudis, symbolizing freedom and release from combat. When Flamma’s moment came, the crowd’s demand was unanimous.

“After one of his most brilliant fights, the enthusiastic crowd voted Flamma the coveted wooden sword.”

But he refused.

“Are you crazy?”

he shouted to the stands.

“I’m making more money than anyone in Rome. I can have any woman I want, I’m living in a villa and I’m the toast of the empire. Leave the arena? What for?”

The crowd laughed and cheered — “Good old Flamma!” — for he was the only gladiator ever to reject freedom not once but four times. His name endured because of that choice. When he finally retired, he was given an ivory identification tag, engraved with his name and that of his owner, and lived to old age, boasting that the gladiators of his youth had been braver than those of later days.

Flamma’s attitude was not entirely unique. Some gladiators, like the Myrmillo, complained of wasted years when fights were scarce, and others, as the philosopher Epictetus observed, prayed for more combats to win glory and fortune. Epictetus, a Roman writer, says that the gladiators used to pray for more fights so that they could distinguish themselves in the arena and make more money. (Those about to die, by Mannix, Daniel Pratt)

While Daniel P. Mannix brought the arena to life with the emotional weight and sensory detail of a novelist, historical research provides a colder, more systematic picture of the men who fought there.

Beneath the color and spectacle, the world of the gladiator was ruled by precision, discipline, and the expectations of a bloodthirsty audience. Archaeology, epigraphy, and Roman accounts reveal the routines, rewards, and grim realities behind the myth — the daily lives of fighters like Flamma, who lived and died according to the rhythm of the arena.

Historical Accuracy on Life, Death, and the Economy of the Arena

Apart from their armor, gladiators usually fought and trained wearing only their undergarments, as the Romans considered complete nudity improper. Greek-style athletics, with their emphasis on naked exercise, never fully suited Roman sensibilities. For gladiators, however, two practical concerns dictated their attire:

- The first was the expectation of blood and visibility — excess armor would hide the spectacle of wounds, depriving the crowd of what they came to see.

- The second was hygiene. Without modern medicine, open wounds were easily infected, and fragments of wool or linen from heavier garments could worsen them.

Thus, most gladiators fought wearing only a subligaculum, a triangular linen cloth about four feet on each side, tied around the waist and pulled between the legs. Ordinary Romans used unbleached linen for this garment, rarely seen in public.

Gladiators, by contrast, wore versions richly decorated with embroidery, ribbons, or bright colors, often held in place by a thick leather belt decorated with metal plates that offered minimal protection to the abdomen.

After months of intense training, a novice was finally introduced to the arena. Beginners were rarely pitted against veterans — such pairings would end too quickly to please the crowd. Instead, novices fought one another, and casualties were high.

Lacking the reflexes and defensive skills of experienced fighters, many were killed outright or mortally wounded. Those who survived often still faced death at the whim of the spectators, as they had not yet earned the admiration that might win them a missus — the signal of mercy. Few survived long enough to become seasoned professionals.

For those who did, the odds improved. Epitaphs and monuments erected by and for gladiators reveal that veterans often won as many reprieves as victories. Skilled fighters could rely on their supporters’ cries for mercy if defeated, as fan clubs frequently rallied to save their favorites.

Flamma of Syria was one of the most successful of all, fought thirty-eight times, winning twenty-five bouts, drawing nine, and losing only four — and even then, being spared (as already mentioned). His career, spanning thirteen years, averaged one appearance roughly every four months — the rhythm of a life bound to blood.

Victories brought not only fame but also tangible rewards. A palm branch marked each triumph, carried in procession before the crowd, and prize money was awarded according to prearranged agreements between the editor of the games and the lanista of the troupe.

Sometimes, when a fighter gave an exceptional performance, the spectators themselves demanded additional rewards. The Emperor Claudius, known for indulging the crowd, would raise each coin before the arena, letting the people count aloud as he dropped them into the gladiator’s hand.

Despite their enslaved status, gladiators were allowed to own property and money. Some spent their winnings on pleasure — food, drink, or women — while others supported wives and families or saved toward freedom. Yet this success came with a paradox. The better a man fought, the more valuable he became to his master. A lanista could grow too greedy to release his prize fighter, knowing his skill brought steady income.

Those unable to buy their freedom often turned to less dangerous work within the ludus. The most talented might be retained as trainers or doctors, passing on their knowledge to the next generation. The injured or maimed might serve as cooks, attendants, or even curiosities at dinner parties, recounting their exploits for wealthy patrons.

The rudis, a simple wooden sword, symbolized the greatest possible reward: freedom. It was sometimes granted by a generous editor seeking favor with the crowd. The gesture was both political and theatrical — freeing a famous gladiator could electrify an audience and secure votes in future elections.

But even freedom did not always mark an end. Many former gladiators remained within the system as trainers or entrepreneurs, founding schools of their own, while others, tempted by vast offers, returned to the arena. Some were offered estates and slaves to fight again.

The world of the arena promised glory, wealth, and adoration — yet its foundation was death. Every triumph was built upon a corpse, every cheer upon a life extinguished. Defeated fighters were taught to die well.

Those who fell without mercy could kneel, grasping their opponent’s knee to expose the neck for a swift, ritual killing. Others, too injured to kneel, were dispatched with a single thrust to the heart. Their bodies were carried away for burial, though most received no tombstones unless their comrades pooled money to honor them.

The life of a gladiator offered gold, fame, and the worship of the crowd, but for the majority, it was brief, painful, and violent — a profession where every victory postponed death rather than escaped it. (The age of the gladiators. Savagery and spectacle in ancient Rome, by Rupert Matthews)

Flamma and the Paradox of Freedom

The epitaph of Flamma, carved in stone near Syracuse, remains one of the most extraordinary testimonies to the mindset of Rome’s gladiators. It records a man who fought thirty-four times, lived thirty years, and, most strikingly, was offered the wooden sword of freedom four times — yet refused it each time, a decision that still defies modern understanding.

To the modern reader, this decision seems unfathomable, but within Rome’s moral framework it revealed something profound. In the arena, virtus and gloria—courage and fame—were not abstract ideals but living currencies of honor.

To fight was to exist; to win was to be remembered. Freedom meant obscurity, the fading of cheers, the silence of forgotten names. Flamma’s choice was therefore not madness but conviction: he preferred to meet his death beneath the eyes of thousands rather than vanish into anonymity.

His story, preserved in a few chiseled lines of Latin, endures as one of Rome’s clearest expressions of how glory could conquer liberty. In the end, Flamma’s legend reminds us that in Rome, a man’s freedom was fleeting, but his name, once won in the arena, could outlive empires.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: