Emperor Domitian: Tyrant or Reformer?

Emperor Domitian, who ruled Rome from 81 to 96 CE, is one of the most polarizing figures of the Roman Empire. Dismissed by many ancient writers as a tyrant and remembered for his strained relationship with the Senate, Domitian’s legacy is one of complexity and contradiction.

Domitian was complex. On the one hand, he strengthened the Empire's administrative systems, maintained stability in the provinces, and achieved significant military victories. On the other, his authoritarian style, harsh punishments, and heavy censorship led to his vilification in historical accounts, many of which were shaped by his senatorial enemies.

By examining Domitian from multiple perspectives—his governance, relationships with the Senate, provincial policies, and cultural contributions—we can gain a deeper understanding of the man behind the myths and the ruler who left a profound yet controversial mark on Rome’s history.

Tyrant, Administrator, and the Historical Context of Revelation

Ancient sources, both secular and ecclesiastical, have long portrayed Emperor Domitian as a tyrant who oppressed the Roman aristocracy and persecuted the Christian Church, with his reign increasingly characterized by terror, particularly in its later years. Recent scholarship, however, has challenged this traditional depiction, offering a more rehabilitated image of Domitian as a capable administrator with flaws no different from those of other emperors.

This reevaluation raises significant questions, particularly regarding the historical accuracy of Domitian’s alleged persecution of Christians and his suitability as a backdrop for interpreting the Book of Revelation.

A painting of the Apocalypse, depicting Emperor Domitian on the left and Saint John in a boiling cauldron on the right, by Albrecht Dürer

Some scholars continue to defend the older portrayal, particularly in modern commentaries on Revelation, while others reject the notion of Domitian as a tyrannical despot. To better understand Domitian's reign, an evaluation of ancient sources—including epigraphic and numismatic evidence—is necessary. These sources provide valuable insights but must be critically examined for their reliability in constructing a comprehensive profile of the emperor.

Additionally, Domitian’s reign has been traditionally associated with the themes of Revelation, particularly due to claims regarding his use of divine language and the imperial cult. Revelation 13:15-17 appears to reflect this ancient phenomenon of emperor worship, making it crucial to investigate Domitian’s relationship with this religious tradition. Understanding the historical setting of Revelation requires a deeper exploration of the imperial cult, as well as a balanced interpretation of Domitian’s character and rule.

The Emperor’s Relationship with the Senate and Historical Bias

The scholarly reassessment of Emperor Domitian has prompted significant debates about the reliability of ancient sources in constructing his historical image. Domitian, traditionally depicted as a tyrant and oppressor of the Senate, has been reinterpreted by some historians as a competent administrator.

K.H. Waters, a prominent advocate of this revisionist view, described Domitian as "a moderately decent man" and dismissed the credibility of sources like Pliny’s Panegyric, comparing its value to relying on the speeches of political opponents to understand a Central American politician. Waters’ critiques reflect broader skepticism about the objectivity of the literary sources, which were influenced by the biases of Roman aristocrats and their contentious relationship with the emperor.

R.P. Jones, another notable scholar, attributes the distorted portrayal of Domitian to the inherent biases of the senatorial class and the judgmental standards they applied to his reign. Unlike his father Vespasian, who cultivated necessary, though imperfect, relations with the Senate to establish the Flavian dynasty, Domitian faced different circumstances.

With the dynastic principle firmly entrenched and his legitimacy unquestioned after the deification of his father and brother, Domitian did not depend as heavily on senatorial approval for his authority. While Domitian initially sought senatorial support at the start of his reign, the relationship deteriorated over time.

Ancient sources such as Suetonius and Tacitus vividly recount the growing animosity, with Domitian’s rule later described as a period of terror and purges targeting senatorial elites. Tacitus famously noted that the Senate was surrounded by armed men and consular senators were executed.

Despite these dramatic accounts, modern scholarship underscores the need to critically evaluate the biases of these sources, as the aristocratic perspective likely colored their depictions of Domitian’s actions and policies. This reconsideration of Domitian’s reign highlights the complexities of using ancient sources to understand his relationship with the Senate and raises broader questions about how historical narratives are shaped by political and social dynamics.

Tacitus and Domitian: Hatred, History, and the Challenge of Interpretation

Tacitus, one of Rome’s most acclaimed historians, lived and thrived in the corridors of power during the Flavian dynasty, achieving remarkable career success under Domitian. Despite the personal benefits he received, Tacitus harbored a profound hatred for Domitian, whom he viewed as a tyrant who revived imperial despotism, stifled free speech, and diminished the Senate's authority.

This animosity permeates his works, leading some scholars to question the reliability of his accounts of Domitian's reign.

Stadium of Domitian on Palatine Hill, in Rome. Credits: starmaro from Getty Images, by Canva

Ronald Mellor, a leading scholar on Tacitus, argues that while Tacitus held strong views against Domitian, his narratives were not fabrications. Mellor describes Tacitus as an advocate presenting evidence to posterity, arranging facts to support his moral and ideological condemnation of tyranny.

Tacitus’s intent, Mellor suggests, was not to provide a dry, factual chronicle but to explore deeper moral lessons and offer exempla for future generations. His hatred for Domitian did not necessarily undermine the factual basis of his accounts, though it certainly influenced their presentation and tone.

Tacitus’s ideological revulsion of absolute power used tyrannically, as epitomized by Domitian, contrasts with his apparent tolerance for rulers like Trajan, whose regime masked similar power under a benevolent guise. While Tacitus never completed a promised work on Trajan, his record of Domitian remains a cornerstone of Roman historiography.

It provides a vivid, albeit subjective, perspective on Domitian's reign, reminding readers of the complex interplay between personal bias and historical truth. To dismiss Tacitus’s evidence entirely would overlook its value as both a historical source and a moral reflection on the nature of tyranny.

Suetonius on Domitian: Balancing Biography and Critique

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, a prominent Roman biographer active during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian, authored The Twelve Caesars, a groundbreaking work that blends elements of history and biography. Suetonius’s portrayal of Emperor Domitian reflects a complex and nuanced perspective, contrary to claims by some modern scholars who dismiss his work as overly biased or gossipy.

Critics accuse Suetonius of being a mouthpiece for the Antonines and of presenting an overly negative view of Domitian. However, a closer reading of Suetonius’s text reveals a more balanced depiction. While Suetonius does highlight Domitian’s cruelty, cunning, and tyrannical tendencies, he also acknowledges the emperor's early efforts to dispense justice, enforce administrative reforms, and exercise restraint in his personal conduct.

For example, Suetonius praises Domitian’s conscientiousness in justice, his initiatives to address agricultural neglect, and his generosity during the initial years of his reign. Suetonius also notes Domitian’s achievements, such as restocking libraries and maintaining personal restraint in his financial dealings, challenging the overly simplistic critique of him as purely a tyrant.

However, Suetonius does record instances of odd and unverifiable anecdotes, such as Domitian catching flies in solitude, which raise questions about their source and authenticity.

A possible representation of Emperor Domitian stabbing a fly in his study. Illustration: Midjourney

Despite these quirks, Suetonius’s narrative aligns with the broader understanding of Domitian as an emperor whose reign began with promise but descended into violence and paranoia. While his work must be contextualized within his ties to the Antonine patrons and his literary goals, dismissing Suetonius entirely as a biased or unreliable source overlooks the depth and complexity of his portrayal of Domitian. (Domitian, by Hamilton Moore and Philip McCormick)

Domitian: A Tyrant or a Reformer? Reevaluating His Reign and Legacy

Reading more about the reign of Emperor Domitian, we keep finding it is often characterized by ancient and modern sources as one of tyranny and cruelty, something that invites reconsideration in light of evidence highlighting his administrative reforms and sense of justice.

While Domitian’s actions, such as the execution and exile of senators and philosophers, fueled his negative portrayal by senatorial historians like Tacitus and Pliny, a deeper analysis reveals a more complex ruler. Domitian's conflicts with the Senate stemmed from his focus on centralizing power and addressing social and economic inequalities within the provinces.

Evidence from inscriptions, provincial accounts, and policies demonstrates Domitian's efforts to protect lower-class provincials from exploitation by local elites and senatorial governors. His measures to regulate grain prices, oversee endowments, and support small farmers underscore his commitment to social justice, even as they antagonized the senatorial aristocracy.

Though Domitian’s heavy-handed methods and autocratic tendencies fueled opposition and culminated in his depiction as a "greedy monster," his governance laid the groundwork for later emperors like Trajan to continue reforming provincial administration.

Domitian’s reign was undeniably marked by terror for his opponents, but it also reflected a genuine effort to maintain imperial stability and fairness for the broader population. This dual legacy demands a balanced evaluation, recognizing both the flaws in his autocratic approach and the enduring impact of his administrative reforms. (Domitian, The Senate and The Provinces, by H.W. Pleket)

Domitian's Early Years: Shaped by Shadows and Expectations

The first 18 years of Emperor Domitian's life remain largely undocumented, leaving historians to rely on fragmentary and often biased accounts. Born into the rising Flavian family, Domitian's childhood unfolded in a household influenced by his father Vespasian's modest political ambitions and fluctuating fortunes.

While Suetonius and Tacitus offer glimpses of his youth, their accounts are colored by the hostility of the senatorial tradition, depicting Domitian as predisposed to tyranny from an early age. The Flavian family's narrative of poverty and simplicity, often exaggerated for propaganda purposes, contrasts with their substantial wealth and connections that enabled their rapid ascent to senatorial status.

Domitian's education and upbringing adhered to the norms of Rome's elite, and he likely benefited from a well-rounded education, despite Suetonius' dismissive remarks. However, the early deaths of his mother and sister, along with the prolonged absence of his father and brother due to military and political responsibilities, may have contributed to a sense of detachment and self-reliance.

Domitian's early life was marked by the shadow of his elder brother Titus, whose achievements and proximity to power possibly inspired both admiration and rivalry.

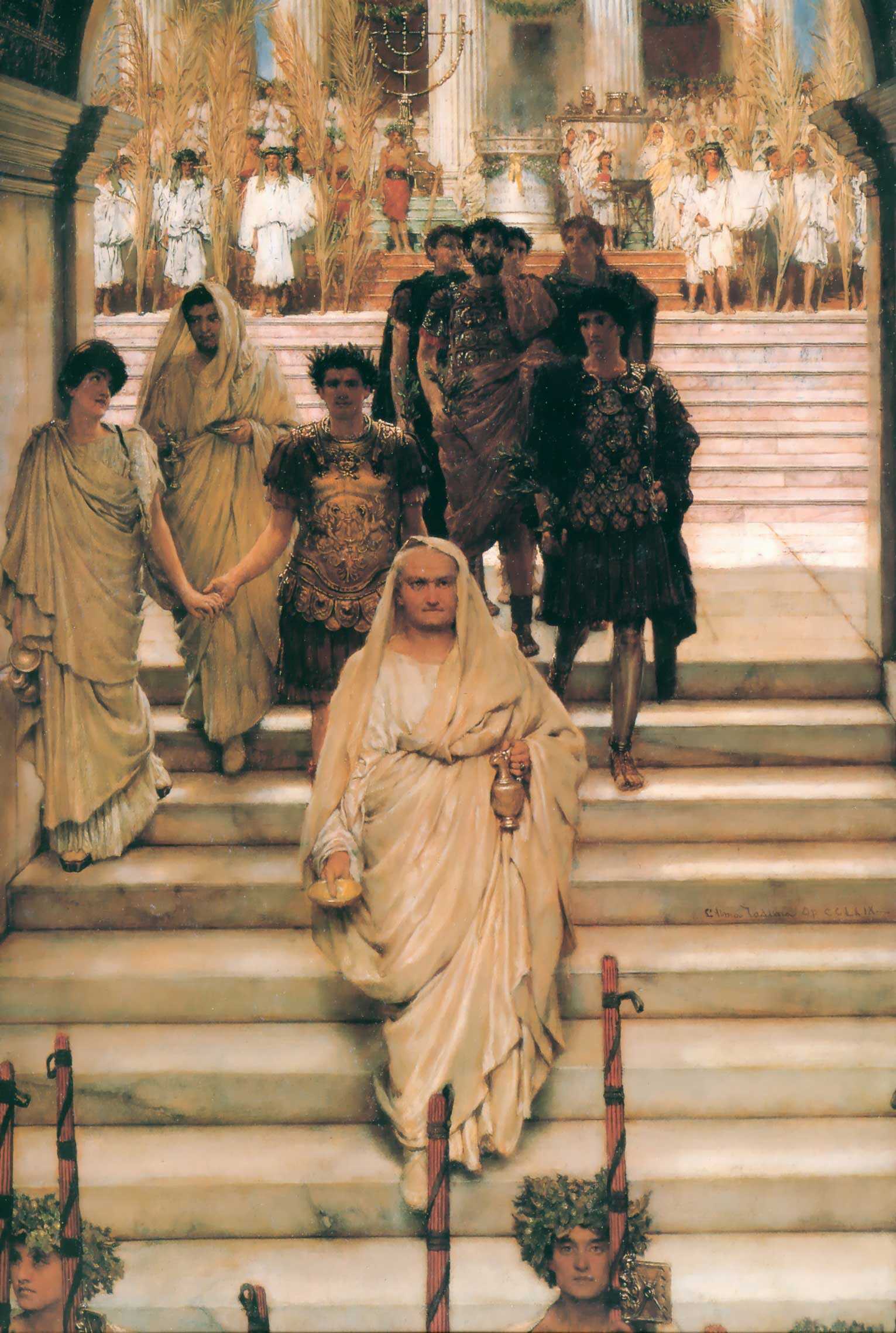

A painting depicting the Triumph of Titus, by Lawrence Alma Tadema. Public domain

The portrayal of Domitian's formative years, heavily influenced by posthumous bias, underscores the challenge of separating fact from retrospective interpretations. By the time Domitian entered history during the Civil War of AD 69, he had transitioned from obscurity to prominence, shaped by familial dynamics and the political currents of the Flavian rise to power. (Domitian. Tragic Tyrant, by Pat Southern)

Domitian was born in Rome on October 24, 51 CE, during the eleventh year of Emperor Claudius's reign. Tradition holds that his birth took place at the family home on Pomegranate Street (possibly modern Via delle Quattro Fontane) on the Quirinal Hill in Rome's sixth region.

Later in his life, Domitian transformed this residence into the opulent Temple of the Gens Flavia, adorned with marble and gold. Following its destruction by lightning in 96 CE, the event was widely interpreted as a symbol of the emperor’s mortality. Upon his death on September 18, 96 CE, his ashes were combined with those of his niece Julia by their nurse, Phyllis, and placed within this temple.

Suetonius relays rumors about Domitian’s impoverished youth, including claims that his family lacked silver plate and that he resorted to selling himself to senators, including the future emperor Nerva. However, even Suetonius acknowledges these stories are dubious.

In reality, the Flavians were far from poor. Wealth, along with influence and ability, underpinned their rise to prominence. Domitian's grandfather, Titus Flavius Sabinus, was instrumental in accumulating the resources that propelled the family into the aristocracy. The Flavians’ origins trace back to Domitian’s great-grandfather, Titus Flavius Petro, who hailed from Reate (modern Rieti) in Sabine territory.

Petro served in Pompey’s army at the Battle of Pharsalus but fled after the defeat. Despite this setback, Petro’s career rebounded as he became a moneylender and married the wealthy Tertulla, whose estates in Cosa and other assets significantly bolstered the family’s fortune. These resources, combined with Petro’s financial acumen, laid the foundation for the family’s rise.

Domitian’s grandfather, Titus Flavius Sabinus, capitalized on this wealth by excelling as a tax collector in Asia and banker in Switzerland. He further elevated the family’s status through marriage to Vespasia Polla, whose family boasted ancient renown.

This union solidified the Flavians’ entry into the emerging aristocracy of the early Empire, a new elite formed as the traditional noble families dwindled in the wake of Rome’s civil wars. By the third generation, the Flavians had secured senatorial status. Sabinus’s wealth enabled both his sons, Vespasian and Sabinus II, to pursue senatorial careers, each meeting the financial requirement of one million sesterces.

Though the family may have once been “obscure and without ancestral portraits,” as Suetonius notes, the Flavian dynasty ultimately produced three emperors and a total of thirty-nine consulships among its male members, marking a meteoric rise from modest beginnings to imperial dominance. (The Emperor Domitian, by Brian W. Jones)

Domitian Reconsidered: Villain or Misunderstood Emperor?

As we research the ancient narratives about Domitian, often written under the influence of the senatorial class, we find they painted him as a tyrant, driven by lust, cruelty, and an insatiable hunger for power. However, this portrayal reflects political motives rather than an objective assessment.

Like Tiberius, Domitian faced vilification due to his contentious relationship with the Senate, whose hostility shaped historical accounts. Writers like Tacitus, Pliny, and Juvenal emphasized his vices, often with little factual support, while ignoring his administrative and military successes.

Despite allegations of neglect, Domitian received significant honors, including consulships and priesthoods, indicating his integral role in the Flavian dynasty. Claims of strained familial relations and unbridled ambition lack convincing evidence, as do accusations of moral depravity, which were often exaggerated to fit anti-tyrannical narratives.

While Domitian’s autocratic tendencies and strained relations with the Senate fueled his negative reputation, his governance displayed administrative efficiency, fiscal responsibility, and a commitment to provincial welfare. Modern scholarship increasingly reevaluates Domitian, challenging the one-dimensional caricature presented by his detractors and recognizing the complexities of his character and reign. This shift highlights the need to balance ancient biases with a critical reassessment, of Domitian’s true legacy.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: