Dining with Domitian and the Enigma of Domitian’s Black Dinner

What was like dining with the emperor? What is the famous black dinner of Domitian? What was the meaning behind the black decoration and the macabre settings?

In the flickering light of dim oil lamps, a select group of Rome’s elite gathered for a dinner unlike any other. The walls, draped in black, seemed to close in on them, and their names etched onto gravestones only added to the suffocating unease. Whispers of unease filled the air, but no one dared speak above a murmur.

This was not just a meal—it was a chilling spectacle orchestrated by Emperor Domitian himself, a ruler as infamous for his paranoia as for his theatrical flair. What unfolded that night has haunted historical imagination for centuries, leaving us to question: was it a warning, a jest, or something far darker?

Domitian at the Table: From Homeric Feasts to Imperial Shadows

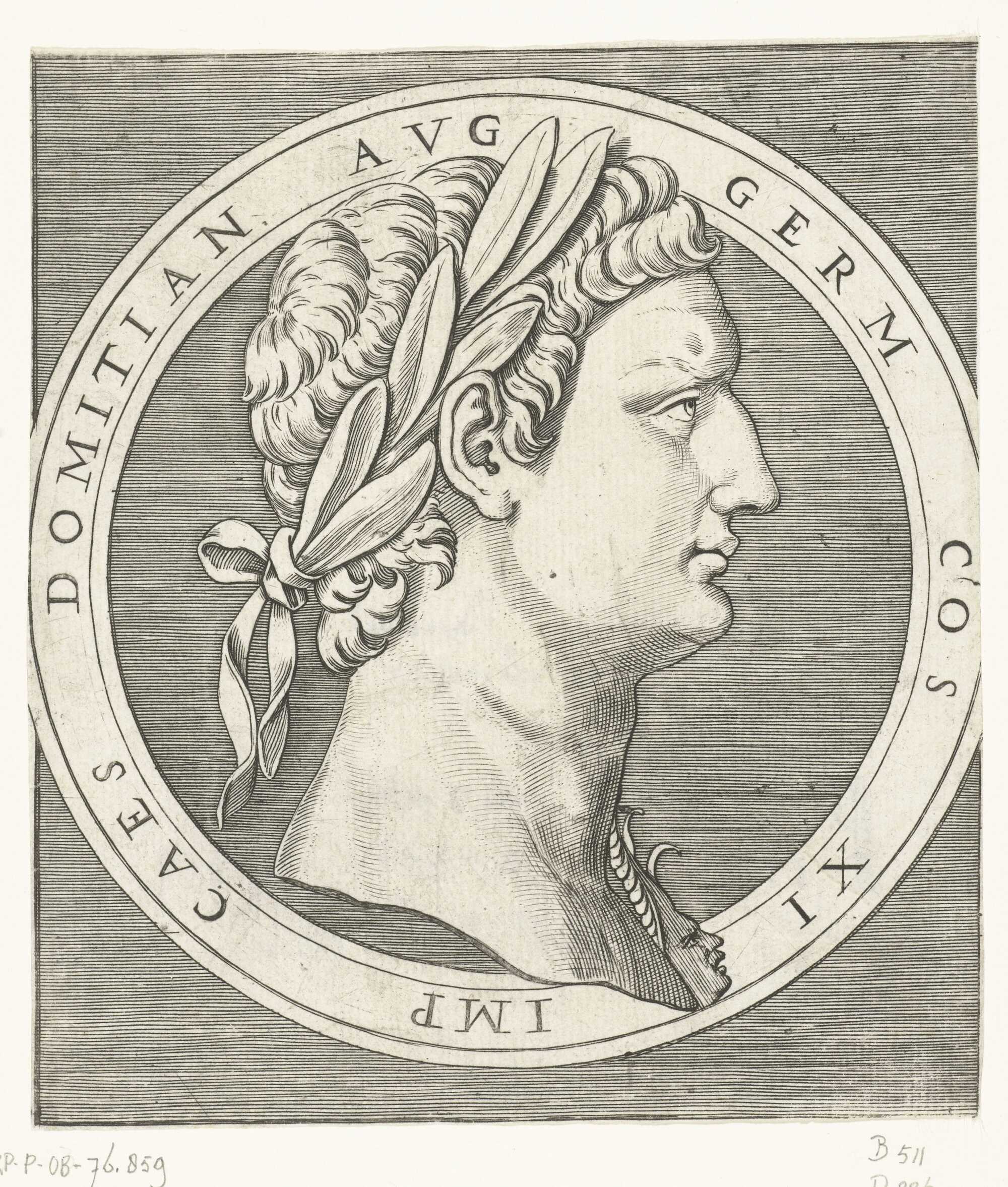

Through the accounts of Dio and Pliny, Domitian has earned a lasting reputation as an unusual—if not outright deviant—host in the annals of Roman dining. Dio provides an elaborate account of Domitian’s infamous “black banquet”, while Pliny, in the Panegyricus, contrasts Trajan’s convivial hospitality with Domitian’s demeanor, depicting him as an archetype of a bad host—gloomy, withdrawn, and foreboding, like a beast lurking in its lair.

Yet, Susanna Braund (a professor of Latin poetry and its reception at the University of British Columbia) points out that poets contemporary to Domitian often celebrated his hospitality. Lavish banquets were a key element of Domitian’s portrayal of himself as a benevolent ruler, as evidenced in Statius’s Silvae, which reflects the panegyrical tone surrounding this theme.

However, Carole Newlands (a scholar of Latin literature and culture, a distinguished professor and associate chair of undergraduate studies at the University of Colorado Boulder) has offered a nuanced perspective on Silvae, showing that these works cannot be reduced to straightforward praise. Instead, her analysis reveals complex layers that challenge traditional readings of Statius’s poems as mere flattery.

In this context, Silvae, stands out as a revealing depiction of Domitian’s role as host, likely describing a banquet the poet himself attended. Statius anchors his narrative in the tradition of epic poets like Homer and Virgil, not only as chroniclers of heroic deeds but as masters of portraying feasts. Through carefully constructed allusions, Statius offers a portrait of Domitian that aligns intriguingly with the later negative depictions of his hospitality, blending praise with an undercurrent of ambiguity:

“He praises the royal feast of Sidonian Dido, that one who brought great Aeneas to the Latin shores, and the banquets of Alcinous are set forth in everlasting song by the one who exhausted Ulysses as he returned over the endless ocean.”

Epic feasts, as described by Statius, follow a familiar narrative arc: a shipwrecked hero is warmly received by a generous monarch, who provides hospitality and hosts a grand banquet in the hero's honor. During the feast, a respected bard performs, the hero recounts his adventures, and the monarch bestows gifts to aid the hero’s onward journey. While the emphasis and details differ, certain elements remain consistent.

In Homer’s depiction, all the senses are engaged at the palace of Alcinous. Odysseus is treated to a hot bath, anointed with oil, and feasts on wine and pork glistening with fat, while listening to Demodokos’s song. Vergil’s portrayal of Dido’s banquet, though less vivid in sensory detail, highlights soft napkins, bread, wine, incense, and the lively sounds of guests. The visual splendor of the banquet hall is emphasized, with light and gold illuminating the scene.

Statius mirrors these traditions in his epic Thebaid. In Book 1, Adrastus’s banquet to welcome Tydeus and Polynices recalls elements from Homeric and Virgilian feasts: couches draped in gold and purple, polished wooden tables, golden lamps dispelling the darkness, roasted meat, and baskets overflowing with bread. This scene blends the grandeur of mythological feasts with the sensory richness that defines epic hospitality.

“The servants rush to obey his orders; a busy din clatters and echoes through the royal hall.

Some spread out the couches, rustling with delicate purple and gold, and pile them high with embroidered covers; some polish the smooth tables by hand and arrange them in order; but others set forth to conquer the darkness and shadowy night, and hang golden lamps from chains.

Some have the task of roasting the bloodless meat of slain animals on spits, while others crush Ceres with a stone and fill the breadbaskets.

Adrastus rejoices at the energy humming through his house.

And now he himself took his seat upon an ivory throne, gleaming amid the splendid tapestries.”

Statius vividly depicts the sensory richness of Adrastus’s banquet in Thebaid, emphasizing the sounds of preparation, the luxurious textures of fabrics, and the opulence of gold and lamps that illuminate the hall. Unlike traditional epic banquets, there is no bard present. Instead, Adrastus himself takes on the role of storyteller, offering a grim tale to entertain his guests.

The opening of Statius’s Silvae 4.2 draws parallels to iconic epic feasts, such as those hosted by Alcinous for Odysseus and Dido for Aeneas. These scenes, rich in sensory details—food and wine for taste, sumptuous fabrics for touch, and music or storytelling for hearing—set high expectations for Domitian’s feast. The audience anticipates Domitian will play the role of a generous host, as Alcinous or Dido did, treating Statius with royal hospitality and prompting him to deliver a brilliant poetic performance in return.

However, the actual banquet diverges sharply from these models. While the visual splendor of the setting aligns with the grandeur of epic feasts, Statius subtly contrasts Domitian’s event with the traditional epic banquet. Instead of a warm, heroic gathering, the focus shifts to the architecture and spectacle of the dining space, where luxury and display take precedence over the expected cultural and poetic exchanges, creating a memorable yet unconventional feast.

"The emperor’s presence in and possession of the space visually is indicated by the apse at the rear wall, the focus of the entire room… despite the huge space, the various marbles, the citrus wood, ivory and slaves arranged in ranks, [the poet] has leisure to gaze only at ipsum, ipsum…

Rather than sharing a hierarchically structured view out of the triclinium, in Domitian’s Iovis Cenatio the guests are subordinated to a view with the emperor at its apex.

As it displays the majesty and authority of the emperor, this reorientation also subjects the guests to a supervisory gaze, not just that of the emperor before them, but one arising from the very awareness that their behavior has become “a performance to be staged.”

Domitian’s banquet, as described by Statius, transforms into a grand theatrical spectacle where even the servants become actors, costumed as mythological figures like Ganymede, Ceres, and Bacchus. This elaborate staging blurs the line between reality and performance, making the dinner a form of immersive entertainment. Domitian himself assumes a role akin to Jupiter, seated magnificently in his apse, underscoring his godlike status.

The sensory experience is dominated by sight, as the overwhelming opulence of the architecture, marble, and lavish decorations engulfs the viewer.

A possible representation of the Roman Emperor Domitian posing as God Jupiter. Illustration: Midjourney

The sheer scale and grandeur of the dining hall render it nearly impossible for the poet, or any observer, to fully grasp its immensity. The spectacle shifts focus from intimate interactions to an awe-inspiring display of wealth and power, where size and visual excess eclipse other sensory elements. This sense of being visually overpowered highlights the hall’s role as a stage for Domitian’s imperial image rather than a traditional setting for hospitality. (A spectacular feast, Silvae 4.2, by Martha A. Malamud)

Imperial Memento Mori: Black Dining and Entertainment under Domitian

Sharing a meal with Domitian was often a challenging ordeal. Dio recounts one particularly unforgettable black dinner with the emperor.

“He prepared a room that was pitch black on every side—ceiling, walls and floor—and had made ready uncovered couches of the same colour resting on the bare floor.

He then invited in his guests alone at night without their servants.

First he set a slab shaped like a gravestone engraved with each guest's name next to them, together with a small lamp like the ones that hang in tombs.

Next [...] naked boys, also painted black, entered like ghosts… and all the things that are commonly offered at sacrifices to the souls of the dead were placed in front of the guests; all of the offerings were black and all in dishes of the same colour.

And so every single one of the guests was terrified and trembling, in constant expectation of having his throat cut the next moment: all the more so because everyone except for Domitian was dead silent, as if they were already in the land of the dead.

The emperor himself held forth only on topics relating to death and slaughter.”

Statius may not have attended Domitian’s infamous late-night feasts, but he experienced the emperor’s hospitality on other notable occasions, as described in Silvae 1.6 and 4.2. In these accounts, Domitian is portrayed as a distant, almost aloof master of ceremonies, hosting events marked by grandeur and excess.

In Silvae 4.2, Statius describes a banquet at the imperial palace featuring a thousand tables, servants costumed as deities such as Ceres, Bacchus, and Ganymede, and luxurious tables crafted from ivory and citronwood—luxuries often criticized by moralists for their association with indulgence. The evening culminated with the awe-inspiring moment when guests were said to catch a radiant glimpse of Domitian himself.

In contrast, Silvae 1.6 recounts an elaborate spectacle in the Flavian Amphitheatre—also known widely as the Colosseum—hosted by Domitian, blending themes of Saturnalian feasting with gladiatorial displays. The event included a shower of sweets, armies of servants, female gladiators, dwarf combatants, exotic birds filling the arena, and celestial fireworks.

Statius, overwhelmed by the extravaganza, admits to drunken exhaustion yet recognizes the enduring significance of the entertainment. The two halves of this poem—one focused on food and conviviality, the other on martial display—offer a tightly woven commentary on the themes of spectacle, power, and indulgence, reflecting broader concerns evident in both the Silvae and Thebaid.

Feasts of Trickery: Saturnalian Banquets and Spectacles under Domitian

Statius’s Silvae 1.6 vividly captures the chaotic and lavish spirit of Domitian’s Saturnalian celebrations, where disorder and excess are woven into both the events and the poem itself. The Saturnalian feast is marked by its departure from traditional structure, embracing reversal, wit, and spectacle, reflecting the festival’s unruly nature.

Statius opens the poem by summoning Saturn, Mirth, and Jokes as presiding deities, setting the tone for an experience of trickery, satire, and mischief. The festivities begin with an amphitheatrical spectacle: the audience is showered with an assortment of exotic treats—nuts from Pontus, dates from Palestine, and pastries shaped like gingerbread men, among others.

This "rain" of food mimics Rome’s conquest and plunder of the wealth of its eastern provinces, transforming the amphitheater into a symbolic arena of Roman dominance. The treats, rich in cultural symbolism, carry playful connotations. The gaioli and lucuntuli, tiny pastries resembling human figures, humorously mirror the ordinary spectators below, while praegnates Caryotides (stuffed dates) evoke layered puns, recalling pregnant Caryatids—female statues punished by servitude, symbolizing Roman dominance over defeated peoples.

These edible symbols of abundance and conquest transition into a grander feast. The amphitheatre fills with handsome servants, dressed as mythological figures like Ganymede, who distribute food, wine, and napkins to the audience. Statius paints this banquet as surpassing even the Golden Age of Saturn, traditionally imagined as a time of labor-free abundance and harmony.

Domitian, celebrated as both the new Jupiter and the host of this Saturnalian feast, embodies divine hospitality. Statius praises him for bringing together all social classes—children, women, plebs, knights, and senators—at a single banquet, reflecting the Saturnalian ideal of social levelling. Yet, even amid this levelling, distinctions persist.

Domitian’s largesse, while inclusive, maintains a hierarchy; senators and knights receive larger hampers of food than the populace. The emperor himself inaugurates the meal, reinforcing his dual role as both participant and ruler. Statius's portrayal cleverly intertwines humor, abundance, and political power, presenting Domitian's Saturnalian festivities as a spectacle of imperial dominance and magnanimity disguised in the revelry of social equality. (That's entertainment! Dining with Domitian in Statius' Silvae, by Martha Malamud)

Feasting in the Shadows: The Macabre Allure of Black Banquets

Throughout history, individuals with a Gothic or Romantic sensibility have used imagery of death, decay, and morbidity as a source of entertainment, creating events that blended fascination and unease. Just as Victor Hugo found drama in the shadowy underworld of 19th-century Paris and William Beckford delighted in his opulent ruin at Fonthill, others crafted macabre spectacles to shock and enthrall their audiences.

One prominent example of this is the "black banquets," which spanned from the Roman era to the Enlightenment. These dinners, steeped in darkness and death-themed symbolism, were designed to provoke, amuse, and sometimes even terrify the participants.

This dramatic interplay between life and death was particularly potent in periods when feasting was still intertwined with funerary customs, offering a stark juxtaposition between grief and the eerie, causeless melancholy associated with such events. These black banquets indulged in a melancholic aesthetic, creating a theatrical contrast to the practical yet often equally unusual role of the traditional funerary feast in mourning rituals.

Feasts of Shadows: The Rituals and Symbolism of Black Banquets and Mourning Feasts in Antiquity

The first documented instance (as previously mentioned) of a black banquet dates back to around 89 CE, hosted by Emperor Domitian as part of the public festivities following the Dacian War. This eerie feast took place in a room entirely painted black, where each guest reclined on a black couch adorned with a mock gravestone bearing their name. The space was illuminated by tomb-like lamps, and the guests were served by boys painted to resemble phantoms. The event is vividly recounted by the historian Dio Cassius in his Roman History.

“All the things that are commonly offered at the sacrifices to departed spirits were likewise set before the guests, all of them black and in dishes of a similar color.

Consequently, every single one of the guests feared and trembled and was kept in constant expectation of having his throat cut at the next moment, the more so as on the part of everybody but Domitian there was dead silence, as if they were already in the realms of the dead, and the emperor himself conversed only on topics relating to death and slaughter.”

Throughout Roman history, food and feasts played a vital role in both mourning and connecting with the dead. Rituals like Dies Parentales and Lemuria underscored the importance of offerings such as black beans, milk, and honey to appease ancestral spirits. Such customs often combined elements of grief, renewal, and communal memory, merging practical mourning with symbolic acts of nourishment for the dead.

Beyond Rome, similar practices were observed in other ancient cultures. The Greeks saw feasting as a bridge between the living and the dead, with elaborate funeral rites designed to honor the departed and bring solace to the mourners. In The Iliad, Achilles provides an opulent feast and a blood ritual to honor Patroclus, forging a symbolic connection between past and future.

The food, blood offerings, and communal dining united the living with the spirit of the deceased, ensuring the soul's peace while enabling the living to continue. Egyptian burial practices also reflected the symbolic importance of food. Tomb excavations have uncovered lavish meals of quail, fish, bread, and fruit, offerings that served as sustenance for the journey to the afterlife.

These rituals emphasized the necessity of honoring the gods and dead through shared sustenance, which, while symbolic, ensured that the spirit would leave the living in peace. In all these traditions, food transcended mere sustenance, becoming a profound medium for connection, remembrance, and ritualistic communication with the divine and the departed. Domitian's black banquet, with its chilling theatrics, likely evoked these ancient customs, merging fear, spectacle, and a dark reflection on mortality. (Melancholy and Mourning: Black Banquets and Funerary Feasts, by Jane levi)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: