Did Slaves Whisper “Memento Mori” to Roman Generals During their Triumph?

The concept of memento mori, Latin for "remember you must die," has been a significant theme throughout history, particularly in the Roman Empire. This idea served as a reminder of human mortality and the transient nature of life.

The concept of memento mori—a reminder of mortality—was not "invented" during the Roman Empire, but the Romans certainly gave it enduring cultural and artistic prominence. The idea of reflecting on death has deep roots in ancient cultures, predating the Romans.

The Origins of the Myth

The notion that a slave whispered "Memento mori" (or a similar phrase) to Roman generals during triumphal processions is an intriguing and widely repeated claim. However, is the historical proof for this practice concrete, or mostly speculative?

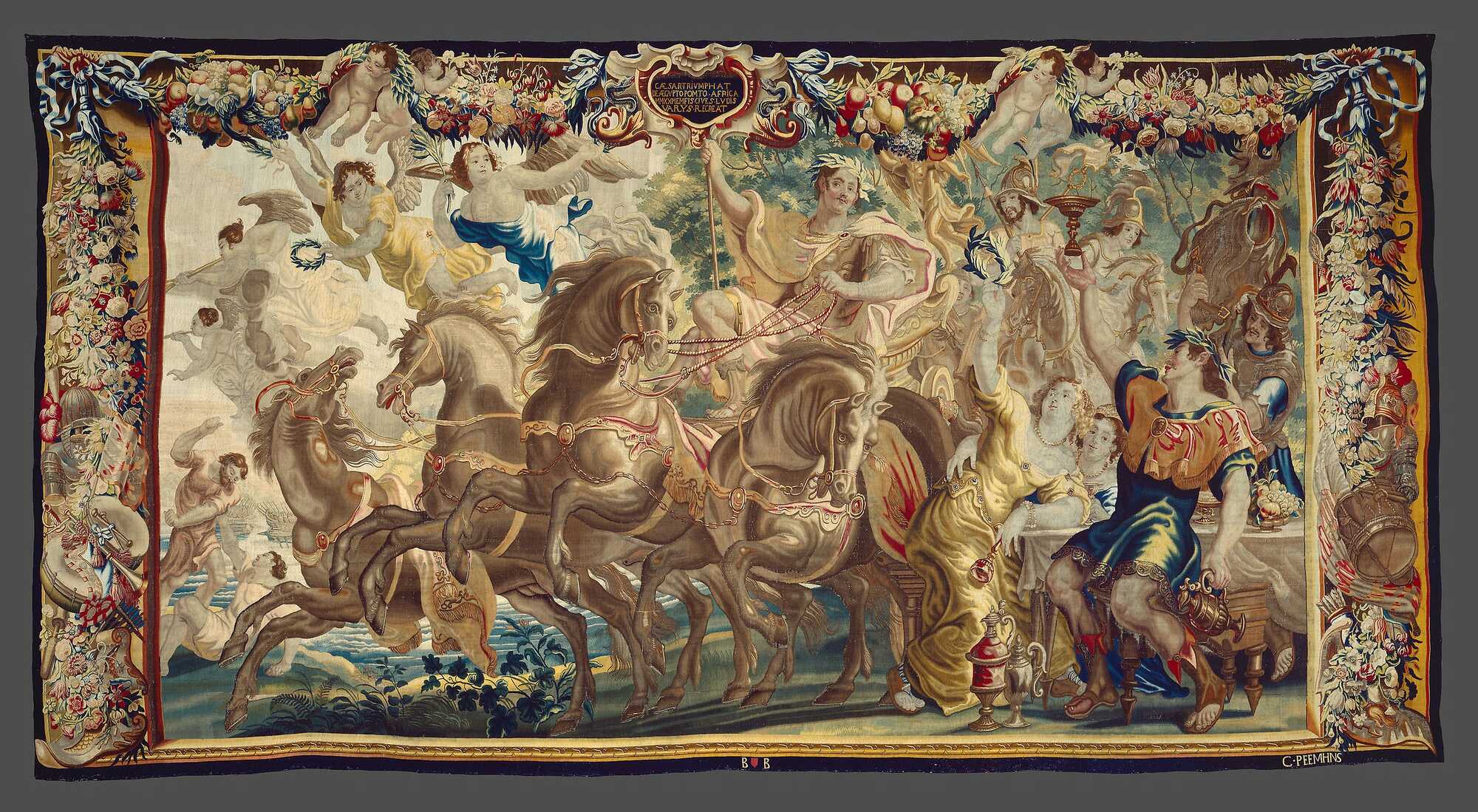

The myth describes a ritual supposedly part of the Roman triumph: a slave standing in the chariot behind the victorious general, holding a golden crown over his head and whispering, "Look behind you. Remember you are a man." This iconic image, often associated with the Roman triumph (and famously depicted in the 1970 film Patton), is widely recognized today.

However, our sources on triumphal practices, including this specific ritual, are incomplete and inconsistent. There is no definitive proof that the slave was a fixed or original element of the ceremony, as often assumed. It is also uncertain whether the crown-bearer was always a slave, and accounts differ on the exact message whispered. The most well-known version of the phrase comes from Tertullian, a second-century CE Christian writer:

“He [the emperor] is reminded that he is a man even when he is triumphing, in that most exalted chariot.

For at his back he is given the warning: ‘Look behind you. Remember you are a man.’ [Respice post te! Hominem te memento!]

And so he rejoices all the more that he is in such a blaze of glory that a reminder of his mortality is necessary.”

Tertullian, Apologeticus 33

Notably, Tertullian does not specify that the figure behind the general was a slave. Jerome, a later Christian writer, referred to the crown-bearer as the general’s companion. Jerome also repeats part of Tertullian’s phrase but likely used Tertullian as his source. It is unclear where Tertullian derived this tradition; he was from Carthage and, as far as we know, never visited Rome or witnessed a triumph.

Other authors provide different interpretations. Cassius Dio, describes a public slave in the chariot who says simply, “Look behind you.” According to Dio, the message was meant to remind the general of life's unpredictability and the potential for disaster, cautioning against excessive pride. Pliny the Elder also briefly references the tradition, though his account is corrupted and unclear. In his writings, Pliny seems to suggest that a slave held the crown in the chariot, adding another layer of ambiguity to the practice's historical accuracy.

“…as a remedy against envy, Fascinus [the embodiment of divine phallus] hangs under the chariots of generals and protects them and a similar verbal remedy urges them to look back in order to conjure away Fortune, the butcher of glory, from following behind him.”

Pliny, Naturalis Historia

The Roman Triumph: A Complex Symbol of Glory and Reflection

Mary Beard's The Roman Triumph offers an in-depth exploration of the meaning and implications of triumphal processions in Roman culture. The Roman triumph was one of the most significant and elaborate rituals of the ancient world, celebrating military victories and asserting Rome's supremacy.

At its core, the triumph was a spectacular procession through the streets of Rome, culminating at the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill, where the victorious general offered sacrifices to the gods.

However, as Mary Beard articulates, this ritual was far more than a straightforward celebration of conquest—it was a deeply layered event that intertwined military success, political rivalry, cultural memory, and even subtle critiques of Rome's imperial values.

The Triumph as Display and Reenactment

Triumphal processions brought the margins of the empire to the heart of Rome, physically manifesting the geopolitics of conquest. Generals paraded with spoils, exotic animals, captives, and placards listing their achievements, transforming the streets of Rome into a theater of victory. This visual and performative spectacle was a powerful tool of propaganda, embedding the narrative of Roman dominance in public consciousness.

It was also a reenactment, allowing the general to restage and reinterpret his battlefield success for a home audience.

A painting of a Roman Triumph, a child is sitting in the triumphator general’s chariot, by Francis William Warwick Topham. Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

Beard emphasizes that these triumphs were not just about the general but reflected broader societal values. They were moments of collective pride and ambivalence, raising questions about the cost and morality of empire. Even within the triumph, the seeds of critique were planted, as the display of wealth and power invited reflections on luxury, greed, and the fleeting nature of success.

Rituals of Memento Mori: Humility Amidst Glory

One of the most debated elements of the triumph is the presence of a slave or attendant whispering a reminder of mortality to the general: “Remember you are mortal.” While this practice is commonly cited, its historical basis is tenuous.

Beard notes that our understanding of this ritual is shaped by fragmentary and contradictory sources, such as Tertullian and Jerome, who offered different versions of the whispered message. Some accounts suggest it was a Christian reinterpretation, emphasizing humility before God, rather than an original Roman practice.

Regardless of its authenticity, the idea of memento mori fits seamlessly into the triumphal narrative. It underscores the duality of the event: a celebration of glory tempered by an acknowledgment of human limitations. The triumph was as much about reflection and self-awareness as it was about dominance.

“Let us compose our thoughts as if we’ve reached the end.

Let us postpone nothing.

Let’s settle our accounts with life every day.”

Seneca

Triumphs were deeply embedded in the competitive culture of Roman politics. They were not only personal accolades but also displays of power that could make or break political careers. Generals often used triumphs to assert their dominance, as seen in Pompey's ostentatious displays of wealth and conquest. Yet, these spectacles also risked backfiring, inviting envy, critique, and even resistance from the public and political rivals.

Triumphal processions also served as cultural touchstones, shaping how Romans remembered and understood their history. The art, architecture, and literature that commemorated these events ensured their impact endured long after the chariots rolled through the city. For instance, triumphal monuments and spoils displayed in public spaces like Pompey's Theater or private residences perpetuated the memory of these victories and their associated values.

Beard challenges the notion that the Roman triumph was an uncritical glorification of imperialism. Instead, she argues that it was a space for reflection on the complexities of Roman identity, power, and morality. Even as the triumph affirmed Rome’s greatness, it allowed for subtle critiques of the very values it celebrated, such as the cost of war, the ethics of conquest, and the impermanence of power.

The accounts of ancient commentators on the tradition of reminding a triumphant general of his mortality are often metaphorical or fleeting, with Cassius Dio being the only one to provide a detailed description of a Roman triumph. Given the diverse, multicultural audience in Rome, interpretations of the triumph would have varied widely. Furthermore, if the tradition dated back centuries, its original intent may have been obscured by the time these commentators wrote about it.

Jerome frames the general's "companion" as analogous to Christian practices that remind individuals of human frailty. Tertullian, on the other hand, uses the tradition as part of a critique against the deification of Roman emperors, emphasizing the irony that, despite a ritual explicitly highlighting the emperor's mortality, it only seemed to inflate the emperor's ego further.

Pliny and Cassius Dio interpret the practice through a religious or superstitious lens. In Roman thought, Fortune or Fate was seen as a capricious and jealous force. The triumphant general, at the zenith of his success, was considered especially vulnerable to Fortune's vengeance, as ancient belief held that excessive pride or superbia could provoke the wrath of the gods. The tradition of reminding the general of his mortality—whether through the presence of a slave or symbols of humility—was thus seen as a safeguard against this divine retribution.

Dio and Pliny suggest the ritual served as a superstitious measure to protect the general from such supernatural risks. Pliny, for instance, mentions the phallus beneath the triumphal chariot as another protective symbol, reinforcing the idea that the triumph was laden with practices meant to ward off envious or malevolent forces. This underscores the Romans’ pervasive belief in the precariousness of success and the dangers of hubris.

When you are having Fun, we will remind you of Death: The Skeleton in Roman Feasting Contexts

During the late Roman Republic and the early Empire, banquets played a multifaceted role in Roman society. These gatherings not only served as occasions for entertainment and forming political alliances among the elite but also acted as poignant reminders of mortality and reflections of aristocratic anxieties about social and political stability.

At this time, skeletal imagery became increasingly common in dining settings, serving as a memento mori during otherwise joyous celebrations. This coincided with the rising influence of Epicureanism in the Roman Empire, leading some scholars to link the proliferation of skeletal motifs directly to Epicurean philosophy, which emphasized the transient nature of life and the pursuit of pleasure.

However, while the connection between macabre imagery and Epicurean thought has been widely accepted, there is little evidence to suggest a direct relationship between this imagery and the specific historical period in which it emerged. Instead, such depictions of memento mori from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE likely reflect the aristocracy's unease regarding their own position and security within the volatile Roman political system.

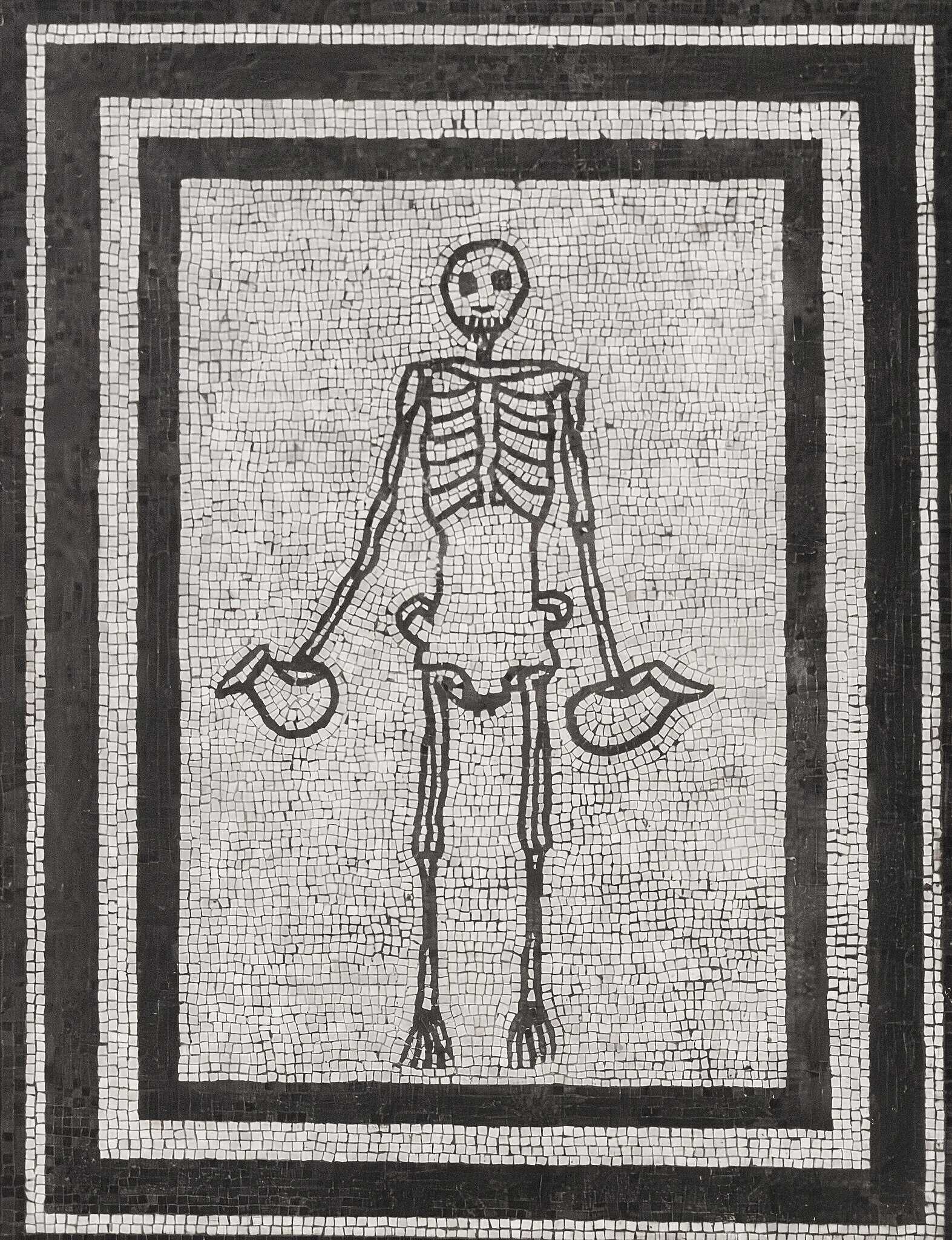

The larva convivialis, a banquet skeleton figurine, served as a poignant reminder of mortality at Roman banquets.

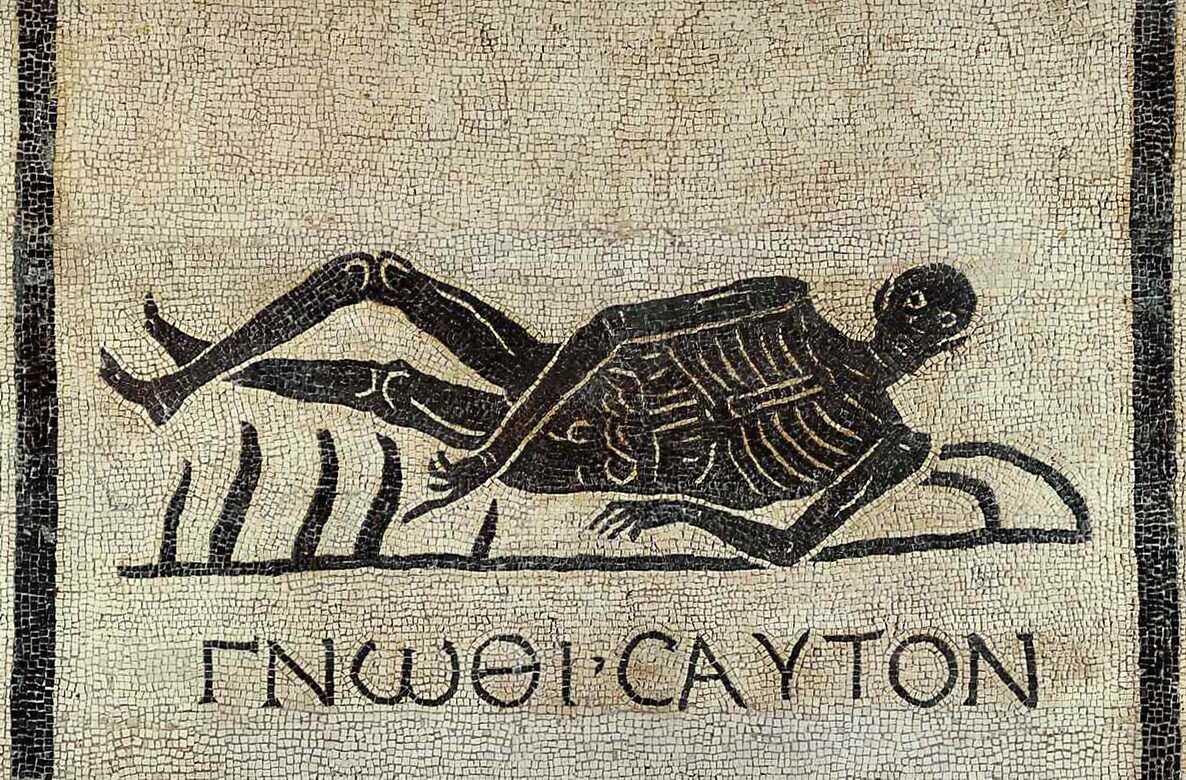

Roman Memento Mori mosaic saying know thyself in Ancient Greek. Public domain

This symbol is not only found in physical artifacts but also described in Roman literature. In Petronius' Satyricon, Trimalchio—a former slave who achieved immense wealth—uses a larva convivialis to underscore the fleeting nature of fortune and life during an elaborate banquet.

To fully grasp the context of the larva convivialis, it is helpful to consider other examples of similar imagery. These include a silver cup depicting the shade of Epicurus and two mosaics from Pompeii: one showing a skeleton holding two askoi and another featuring a skull balanced on scales.

The latter, found in a triclinium (dining room), symbolizes both the inevitability of death and the unpredictable shifts of fortune. These images reminded banquet attendees of life's fragility and the potential for abrupt, often traumatic, changes amidst an otherwise festive atmosphere.

The theme of mortality and shifting fortune, encapsulated by these skeletal images, persisted into the late medieval period. Similar motifs appeared in the rota fortunae (wheel of fortune) and the danse macabre during the plague epidemics, reflecting societal upheaval. While medieval skeletal imagery was not typically tied to feasting contexts, the underlying messages remained consistent.

In Roman feasting contexts from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE, skeletal imagery functioned as a memento mori, reflecting the influence of Epicureanism. However, it also highlighted aristocratic anxieties over social and political instability. The skeleton became both a philosophical reminder of life's brevity and a manifestation of the elite's disquiet during uncertain times. (From: camws.org: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South)

Credits: Jebulon, Public domain — Chappsnet, CC BY-SA 4.0

Analysis of the Memento Mori Mosaic in Pompeii

The Memento Mori mosaic, excavated in Pompeii, provides a rich example of Roman art reflecting cultural values surrounding death and life. It was discovered in the Conceria, placed in a summer triclinium—a dining room with open walls leading to a peristyle garden.

This house, part of a tannery, appears to predate the tannery itself, suggesting an earlier domestic phase. The mosaic, small yet intricately crafted with cuboid tesserae set in mortar, is now preserved in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. Roman triclinia were central to social and political life, hosting dinners that facilitated not just personal camaraderie but also political alliances and displays of status.

Mosaics like the Memento Mori were emblematic of emblemata, intricate artworks carefully placed in triclinia, peristyles, or gardens to command guests' attention. These centerpieces often reflected widely recognized cultural motifs, underscoring the privilege and duty of hosting elaborate displays that revealed aspects of Roman social and cultural values.

The Memento Mori mosaic employs codified imagery to convey its message. Divided into four key segments, it depicts symbolic elements of life, death, and fate. The central feature—a skull—represents mortality, while supporting elements like the libella (a craftsman’s tool) suggest balance and measurement, invoking notions of equity in death.

On one side, symbols of wealth and nobility such as purple fabric, a crown, and a scepter are juxtaposed with symbols of poverty, including a satchel and traveling cloak. This dichotomy underscores the theme of death as the great equalizer, rendering social distinctions irrelevant.

At the bottom of the mosaic, a wheel and butterfly symbolize the transient nature of life and the soul’s journey. The wheel represents fate, while the butterfly signifies the soul’s release from the earthly realm. The mosaic’s composition, with its use of color and shading, creates depth and complexity, enhancing its visual and symbolic impact.

The Roman View of Death and Feasting

Romans associated death with rites of passage, and the carpe diem philosophy was central to their worldview. Feasting and celebrations of life were often intertwined with funerary rituals. Festivals such as the Parentalia, Rosalia, and Lemuria honored the dead, blending solemn commemoration with communal festivities. Objects like the Memento Mori mosaic, however, were not necessarily tied to funerary contexts.

Instead, they often served as reminders to live fully, embracing life’s fleeting nature.

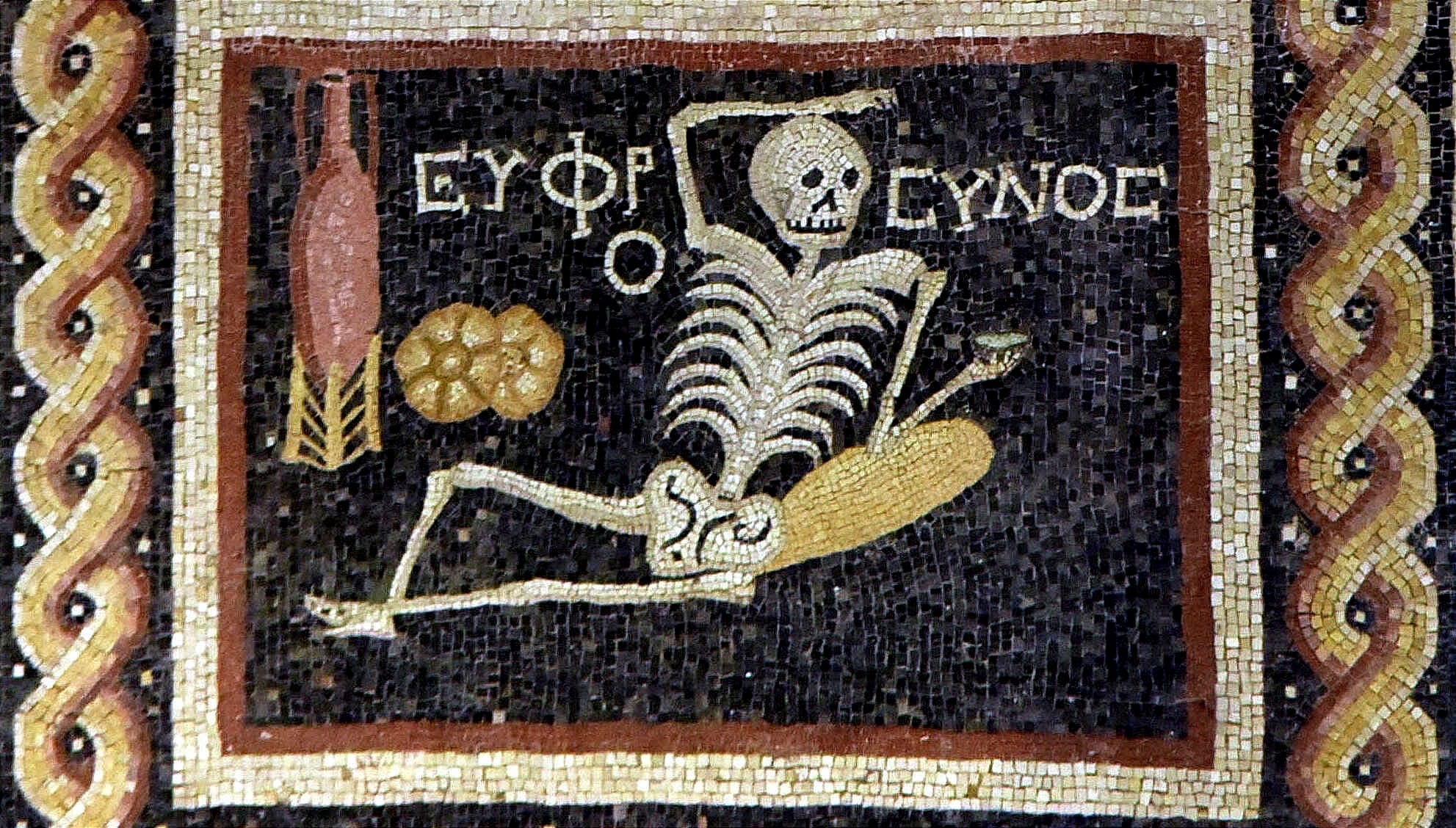

Skeleton Roman mosaic from Antioch saying Euphrosynos, meaning ‘Enjoy, have fun, cheer up.’ Credits: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0

Examples from Roman art, such as silver cups from Villa Boscoreale or mosaics like the skeleton carrying wine jugs in the House of the Faun, reinforce this playful yet contemplative attitude toward mortality. These images suggest an acceptance of death, celebrating life’s pleasures while acknowledging its impermanence.

The Memento Mori mosaic encapsulates a Roman perspective on equality in death, emphasizing the soul and fortune over material wealth. Its placement in a dining room connects the themes of death and feasting, reinforcing the interplay between life’s transience and the enjoyment of the present. The mosaic’s context as a table adornment in a domestic setting raises questions about its specific purpose and placement, which cannot be fully answered through iconography alone.

A multidisciplinary approach, integrating visual analysis with contextual studies of similar objects, such as the bronze weights shaped like skulls with butterflies from the same period, can yield deeper insights. These repeated motifs highlight the cultural significance of the imagery, suggesting a shared Roman worldview on mortality, fate, and the balance of life.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: