Damnatio memoriae: Condemnation and Eradication in the Political Sphere of Rome

Damnatio memoriae was a process of erasing everything there was about a person that was harmful to the Empire.

Damnatio memoriae, a Latin term meaning "condemnation of memory", was a practice in the Roman Empire whereby the state sought to erase all traces of a person from history. This punishment was typically reserved for those who had committed acts deemed exceptionally harmful to the Roman state or its leaders, such as treason or assassination of an Emperor.

The story of damnatio memoriae

Recording history has always been crucial in shaping human experiences. While the passage of time has naturally lost or altered many stories, some histories have been deliberately manipulated.

The intentional erasure of history has served as a powerful tool for individuals aiming to rewrite the past and reshape societal ideals. This tradition includes the Roman practice of damnatio memoriae, which systematically erased individuals from historical records to reconstruct the narrative to suit contemporary agendas.

Damnatio memoriae is a modern term, first appearing in 1689 as the title of a short dissertation published in Leipzig. Today, it collectively and indiscriminately refers to a range of ancient Roman practices directed at convicted traitors, typically posthumously. The term itself is a modern construct and was never used in antiquity. The closest ancient equivalents were the terms "memoria damnata" or "memoria accussare" used by Roman jurists. Nonetheless, the concept of sanctions against memory was very relevant in the Roman world. Romans were well aware that the memory of fallen enemies could be subject to ritualized assaults.

How has the damnatio memoriae put into practice?

We are talking about erasure. Various forms of erasure occurred, ranging from official decrees that required the removal of names from inscriptions and images from funerals, to spontaneous removal or defacement of monuments linked to those disgraced, and literary attacks aimed at damaging reputations after death.

In ancient Rome, damnatio memoriae was the practice of condemning emperors after their deaths. If the Senate or a succeeding emperor disapproved of an emperor's actions, they could have his property seized, his name erased from records, and his statues defaced or altered.

One individual who suffered this irreversible fate was the last Flavian emperor, Titus Flavius Domitianus, commonly known as Domitian. His image was erased from public displays and iconography, and his reputation was tarnished in literature. Due to the economic incentive to seize property and rework statues, historians and archaeologists find it challenging to determine when official damnatio memoriae actually occurred, although it appears to have been quite rare.

Adding to this challenge is the fact that a completely successful damnatio memoriae would, by definition, result in the full and total erasure of the subject from the historical record. For prominent figures such as emperors or consuls, complete success was unlikely, as even thorough obliteration of their existence and actions in records would still leave some traces.

The impracticality of such a cover-up could be substantial—in the case of Emperor Geta, for instance, coins bearing his image remained in circulation for several years, and even mentioning his name was punishable by death. Difficulties in implementing damnatio memoriae also arose when there was not unanimous and lasting support for the punishment.

For example, when the Senate condemned Nero, many of his statues were attacked, but this condemnation was later undermined by the grand funeral organized by Vitellius. Similarly, it was often challenging to prevent later historians from reviving the memory of the condemned individual.

The cases of damnatio memoriae in the Roman Empire

Sejanus

Lucius Aelius Sejanus (circa 20 BC – October 18, AD 31), commonly known as Sejanus, was a Roman soldier and a close friend and confidant of Emperor Tiberius. Born into the Equites class, Sejanus rose to prominence as the prefect of the Praetorian Guard, the imperial bodyguard, and held the position from AD 14 until his execution for treason in AD 31.

Calculating and ambitious, Sejanus, a self-made man with no true aristocratic lineage, was a formidable presence within the imperial household. His rise to power was marked by an affair with Livilla, the wife of Tiberius’s son.

This relationship positioned him at the heart of Roman governance, and he began to harbor ambitions of becoming emperor. After the death of Drusus in AD 23, Sejanus became Tiberius's trusted confidant and essentially the second-in-command of the Empire, described by Tiberius as his "socius laborum" (partner in labor). When Tiberius permanently relocated to Capri in AD 26, indulging in a life of debauchery, Sejanus effectively assumed the responsibility of managing the Empire.

One day in 31 AD, Tiberius had Sejanus denounced in the Senate, imprisoned, and swiftly executed. The execution itself was typical for Roman standards: Sejanus was led out of prison, strangled, and his body thrown down the Gemonian Steps.

However, what happened to his body afterwards was far from standard. For three days, Sejanus’ corpse was publicly displayed, during which it was subjected to beatings by his political enemies and likely opportunistic passers-by. After enduring this public humiliation, his body was thrown into the Tiber River, drifting away from Rome and history.

Tiberius did not stop at Sejanus’s death in obliterating his memory. In an act of numismatic damnatio memoriae, Tiberius recalled a batch of coins minted during Sejanus’s consulship in 31 AD and had them defaced by removing Sejanus’ name. For example, the words "L. AELIO SEIANO" were scratched away on these coins, as seen in historical artifacts.

Livia

Claudia Livia (13 BC – AD 31) was the only daughter of Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia Minor. She was the sister of Roman Emperor Claudius and the general Germanicus, making her the paternal aunt of Emperor Caligula and the maternal great-aunt of Emperor Nero. Additionally, she was both the niece and daughter-in-law of Emperor Tiberius.

Despite being married to Drusus, the emperor’s son and potential heir, Livilla engaged in an illicit affair with Sejanus, the head of the Praetorian Guard. The true nature of their relationship—whether it was based on mutual attraction or driven by strategic motives—remains unknown. Sejanus certainly stood to benefit from aligning himself with Drusus.

Livilla's husband did not live long, dying in 23 AD; the official cause was natural, but it is widely believed that Sejanus had been secretly poisoning him over time. Livilla was actively involved in a conspiracy against Emperor Tiberius in 31 AD. However, a letter from Sejanus’s ex-wife alerted Tiberius to the plot, allowing him to act first.

Tiberius denounced them in the Senate, leading to the execution of Sejanus and his entire family. The circumstances of Livilla’s death are unclear; she either committed suicide or was murdered. Historian Cassius Dio provides a particularly gruesome account, claiming that Livilla was locked in a room and left to starve, with her mother Antonia Minor guarding her.

The Roman historian Tacitus records that in early 32 AD, the Senate officially sanctioned Livilla's memory, decreeing the destruction of all her images. This is notable as Livilla became the first woman from the imperial family to have her memory officially expunged by the Senate.

The measures were highly effective: despite her prominent status as the widow of the emperor’s son and the mother of a potential heir, very few depictions of her have survived. There are no identifiable statues of Livilla; only a series of cameos featuring her distinctive hairstyle (wavy, centrally parted, and tied up in a chignon) allow for her identification. Portraits of the imperial family show instances where her image has been scratched out. Moreover, no inscriptions bearing her name have been found throughout Rome.

Caligula

Caligula's harsh treatment of the Roman elite ensured his negative posthumous reputation. Driven by deep-seated insecurities, he constantly flaunted his authority and mistreated the senatorial class. At banquets, he would take the senators' wives to bed and then publicly critique their performance. When sycophants proposed deifying him, he eagerly accepted, creating a cult around his godhead. Eventually, in 41 AD, fed-up conspirators assassinated Caligula, along with his wife and infant child, as he was leaving the theatre. His assassination triggered chaos, with his German bodyguards killing indiscriminately. The Senate considered abolishing the position of emperor and restoring the Republic.

During this turmoil, a loyal Praetorian Guard discovered Caligula's uncle, Claudius, hiding behind a palace curtain and declared him Emperor at the Praetorian camp. Although Claudius prevented the Senate from formally condemning Caligula, attacks on Caligula's memory and family were severe. Instead of being interred in the Mausoleum of Augustus, Caligula was buried in an unmarked grave to deter the formation of a cult.

The Senate ordered the melting down of bronze aes coins with his image and the defacing of many other coin types. Claudius had their names stripped of imperial titles in the Fasti (political calendars) and had all their images destroyed or stored out of public sight, including artworks, portraits, and sculptures.

Many statues of Caligula were re-carved to resemble his great-grandfather, Augustus, or later transformed into statues of Claudius. Ironically, statues of disgraced emperors like Caligula have often survived better than those of more revered emperors because they were stored away and thus preserved from the elements, unlike the public statues which suffered weather damage. However, despite some statues surviving, Caligula's notorious reputation remains largely intact.

Messalina

Of noble lineage, Messalina was the great-granddaughter of Octavia, the sister of Emperor Augustus. She married Claudius, the future emperor, in 38 or 39 AD, a few years before he ascended to power. Together, they had two children: Britannicus, named after Claudius's conquest of Britain, and Octavia. Both children met tragic ends under Emperor Nero's rule: Britannicus was poisoned, and Octavia, who was Nero’s wife, was brutally executed.

Ancient sources depict Messalina's character in stark contrast to her noble birth. As empress, she was infamous for her extreme promiscuity, allegedly even participating in a sexual competition with Rome's leading prostitute and emerging victorious.

In 48 AD, Messalina attempted to seize power by marrying her lover, Gaius Silius, while Claudius was away in Ostia. Their coup failed when Claudius returned, leading to the arrest and execution of Silius and his accomplices. Messalina was detained briefly before being executed by Claudius's advisors, who feared he might pardon her. Following her death, the Senate moved swiftly to erase Messalina's memory, similar to their actions against Livilla after her conspiracy against Tiberius.

They decreed the complete eradication of her existence: her name was chiseled out from inscriptions, and her image was removed from both public spaces and private homes across the Empire. Such was the animosity towards her that even coins minted in the Greek provinces bearing her name and image were defaced, and many of her portraits were violently vandalized until they were unrecognizable.

Nero

By the time Nero took his own life in 68 AD, thrusting a dagger into his neck while hiding from the Senate and army in a freedman’s shabby villa, his posthumous reputation was already irredeemable. Nero had alienated large segments of Roman society through his egregious misrule. His death not only marked the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty but also triggered over a year of violent civil war, which an emperor was supposed to prevent.

Declared an enemy of the state (hostis) by the Senate, Nero underwent a de facto damnatio memoriae. Although no official senatorial decree was issued to obliterate all traces of his reign, his name and images were attacked, erased, or removed from public view and stored away. However, he still retained some popularity among the common people. His tomb was frequently adorned with flowers, and several “False Neros” emerged across the Empire, attempting to capitalize on his name for power.

During the brief reigns of two of his successors, Otho and Vitellius, Nero experienced a short-lived rehabilitation in 69 AD when his statues reappeared in public. Otho had personal ties to Nero, having been married to Nero’s wife, Poppaea Sabina, while Vitellius, a friend of Nero, often praised his artistic talents and encouraged his performances. However, Vespasian, who ultimately triumphed in the civil war, swiftly reinforced Nero’s damnatio memoriae.

Many of Nero’s statues were re-carved to resemble Vespasian, which was not a flattering comparison to Nero. Vespasian was nearly twice Nero’s age when he took power and had a perpetually constipated expression. Nero’s statues were also altered to represent Augustus, Claudius, Galba, Titus, Domitian, Trajan, and Commodus, among others.

One of Nero’s most iconic images, the "colossus", a giant bronze statue of himself erected after the Great Fire of 64 AD, underwent several transformations after his death. Initially altered to look like the sun god Sol, it was later recast to resemble Vespasian’s son, Emperor Titus, then Hercules, and finally Emperor Commodus.

Domitian

The Senate's memory sanctions against Domitian in September 96 AD were notably harsh. Senators crowded the Senate House, vehemently denouncing his name and reputation. They then used ladders to remove his votive shields and statues, smashing them. They also passed an oblitio nominis, mandating the erasure of his name from all public inscriptions and obliterating all records of his reign.

Suetonius's account of these events is corroborated by archaeological evidence in Rome, which has uncovered few traces of Domitian’s statues or inscriptions. Most of his statues were re-carved to resemble his successor, Nerva. Additionally, Pliny the Younger, a contemporary lawyer and politician, vividly describes the destruction of Domitian’s statues:

“How delightful it was, to smash to pieces those arrogant faces, to raise our swords against them, to cut them ferociously with our axes, as if blood and pain would follow our blows.”

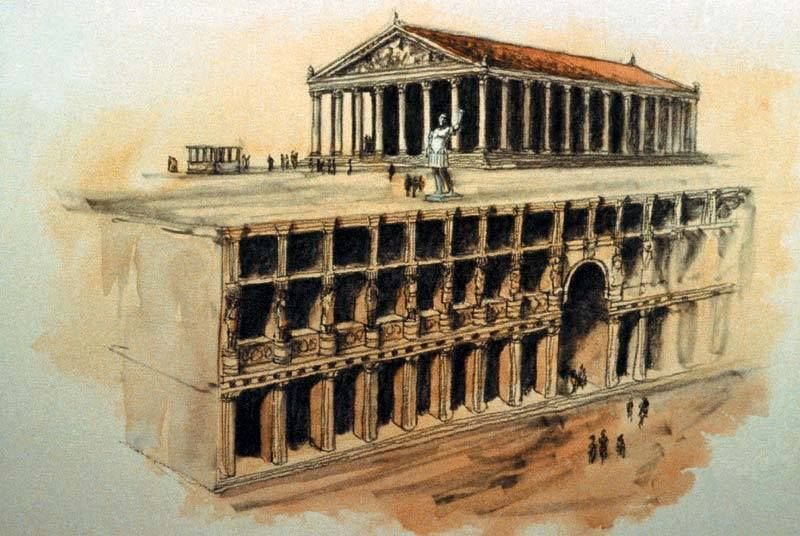

Domitian's memory faced erasure beyond Rome as well. He had favored the city of Ephesus, building aqueducts, extending the city’s boundary, providing tax breaks, and allowing the city to establish a cult in his honor. After his death, Ephesians found a way to cope with this legacy by rededicating the temple built in his honor to Domitian's family, the Flavians, excluding Domitian himself.

Commodus

Ascending to power at just 19, Commodus lacked the aptitude for ruling. Instead of overseeing Senate sessions, he preferred killing wild animals in the arena or using them as targets for archery. His reign of terror included making his Praetorian prefect dance naked through the palace, renaming Rome to “Commodiana”, and changing the months to reflect his honorific titles: Lucius, Aelius, Aurelius, Commodus, Augustus, Hercules, Romanus, Exsuperatorius, Amazonius, Invictus, Felix, and Pius. Inevitably, he was assassinated in 192 AD, strangled in the bath by his wrestling partner Narcissus after surviving a poisoning attempt. The Senate swiftly declared him an enemy of the state, removed his name from inscriptions, demolished his statues, and reversed some of his changes, such as renaming Rome back to its original name.

A valuable yet questionable source allegedly provides a verbatim senatorial decree listing sanctions against Commodus’s memory. It angrily calls for his body to be dragged with a hook, for his statues to be overthrown, and for "the memory of the foul gladiator [Commodus] to be utterly wiped away". However, the decree's repetitiveness and lack of specifics cast doubt on its authenticity. Despite this, the source was correct about the destruction of Commodus's images and inscriptions, reflecting the people's hatred.

Despite his numerous transgressions, Commodus was deified by his successor, Septimius Severus, likely as a political move to appease the family of Marcus Aurelius. However, deification did little to improve his posthumous reputation, and Commodus remains widely regarded as one of Rome’s worst emperors.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: