Crime and Punishment in the Roman Empire: Justice and Inequality

Roman justice was never equal. From trials in the forum to brutal punishments like crucifixion and exile, the law upheld social order through fear and spectacle. This article explores how crime and punishment shaped power in the empire.

Justice in the Roman Empire was as much a display of dominance as it was a legal institution. Beneath the solemn rituals of the courtroom and the rigid formulas of Roman law, a deeply unequal system thrived—one where status dictated not only how justice was administered, but what counted as justice in the first place.

A senator and a slave might face the same charge, but never the same fate. From crucifixions and damnatio ad bestias to exile and fines, punishment in Rome was calibrated to uphold hierarchy, instill fear, and maintain control. In the empire’s sprawling legal machinery, crime was never judged in a vacuum—it was judged in context: social, political, and brutally pragmatic.

The Legal Framework of Ancient Rome

The foundation of Roman law was the Twelve Tables, established in the early Republic. This codification of laws was a response to the plebeians' demands for legal transparency and equality. However, the application of these laws often depended on one's social status, with patricians enjoying more leniencies compared to plebeians and slaves.

The Twelve Tables served as a public declaration of the rights afforded to each citizen within both the public and private domains. These tables codified what had been implicitly understood within Roman society as unwritten laws.

By making these previously unwritten norms accessible, the Twelve Tables offered plebeians a means to assert their rights and resist financial exploitation, contributing to a more balanced Roman economy.

Interpreting Roman Justice: A Legacy of Unequal Punishment

Roman criminal law has intrigued historians for more than a century, especially as it relates to how Rome maintained order across its vast territories. While early legal historians focused on building a clear picture of Rome’s legal system, later scholars began to look more closely at how punishment functioned within that framework.

Rather than treating Roman justice as a static body of rules, more recent approaches have asked deeper questions: Who was punished, how, and why?

A bas-relief of the Goddess of Justice, by Antonio Canova. Credits: Fondazione Cariplo, CC BY-SA 3.0

Interest gradually shifted toward understanding punishment not only as a legal consequence but as a tool of social control. It became clear that Roman penalties—especially harsh forms like execution, torture, and exile—were shaped as much by politics and hierarchy as by law.

Some historians emphasized how Roman ideals like humanitas (humanity) and utilitas publica (public interest) were used to justify punishment that often reinforced inequality. Alongside these ideas, a small but significant thread of research began exploring something unusual: Roman jurists themselves sometimes criticized the laws they applied. This rare legal self-awareness offers a glimpse into the tensions between justice and state power.

Rather than recounting rules and procedures alone, the focus now is on how punishment exposed the deeper workings of Roman society. The goal is to understand law not just as a list of statutes, but as a reflection of how Rome viewed order, obedience, and the human body itself.

In the Forum: How Roman Trials Were Conducted

Criminal justice in ancient Rome operated under principles that were surprisingly participatory—though not always fair. Unlike modern systems where public prosecutors pursue serious charges on behalf of the state, Roman trials were often initiated by private individuals.

A victim, their family, or a magistrate could bring an accusation, and from the late Republic onward, Lex Calpurnia even allowed any citizen to initiate criminal proceedings through a mechanism known as accusatio popularis. This broadened access to justice but also opened the door to political prosecutions and personal vendettas.

Trials were held in the open air, usually in a Roman forum, and presided over by a praetor. This official was responsible for keeping order, administering oaths, managing the schedule of speeches, and announcing the verdict.

High-profile trials often drew large crowds—especially when prominent orators like Cicero were involved—and were conducted with great attention to formality and public perception.

Time limits were strictly enforced. A clepsydra, or water clock, was used to measure the duration of each speaker's address. As water flowed from an upper to a lower vessel, the speech was allowed to continue; when the water ran out, so did the speaker’s time.

The prosecutor spoke first, followed by the defense. Both parties could present evidence, question witnesses, and introduce documents. A unique feature of Roman trials was the presence of character witnesses—friends and relatives of the defendant who testified not about the facts, but about the moral standing of the accused.

This practice reflected the enduring influence of older Roman customs, such as coniurationes—pledges of loyalty and friendship. Judgment was delivered by a panel of iudices, lay jurors drawn from Rome’s upper classes. After hearing the arguments, they cast their votes using clay tablets marked with a “C” (condemno) or “A” (absolvo).

A majority was required for conviction, and in the case of a tie, the defendant was acquitted. Although voting was typically secret, a defendant could request it be made public. The praetor then counted the votes and formally issued the court's judgment.

From Rome to Byzantium: The Evolution of Criminal Procedure

As the Roman legal tradition transitioned into the Byzantine period, the structure of criminal proceedings began to shift. During the reign of Justinian, the process took on more investigative characteristics. Testimonies were recorded in writing, and courts had the authority to summon witnesses who were legally obliged to appear.

Torture, absent from much of early Roman legal practice, emerged more prominently during this era—especially as a method of extracting confessions. At the same time, the law imposed strict limits on who could serve as a witness.

Women, minors, servants, persons with disabilities, business partners testifying in each other’s favor, and even Jews in cases involving Christians were often barred from offering testimony. While these restrictions appear discriminatory by modern standards, they reflected the social and religious hierarchies of the time.

The Byzantine Empire, or Basileia Rhōmaiōn, saw itself not as a new state but as a continuation of Roman identity and law. Its citizens even called themselves Ῥωμαῖοι (Rhomaioi)—Romans. The evolution of its criminal procedure highlights both continuity and change: a legal system that inherited Roman structure, but gradually adapted to the needs and ideologies of a Christian empire.

Punishment in Rome: Death, Exile, and the Pillar of Shame

Roman law prescribed a wide array of punishments, each reflecting the values, fears, and power structures of its time. While the criminal trial ended with a verdict, it was the sentence that left its lasting mark—on bodies, reputations, and property.

Some punishments, like fines or exile, removed a person from civic life. Others were far more brutal and spectacular, meant to serve as public warnings.

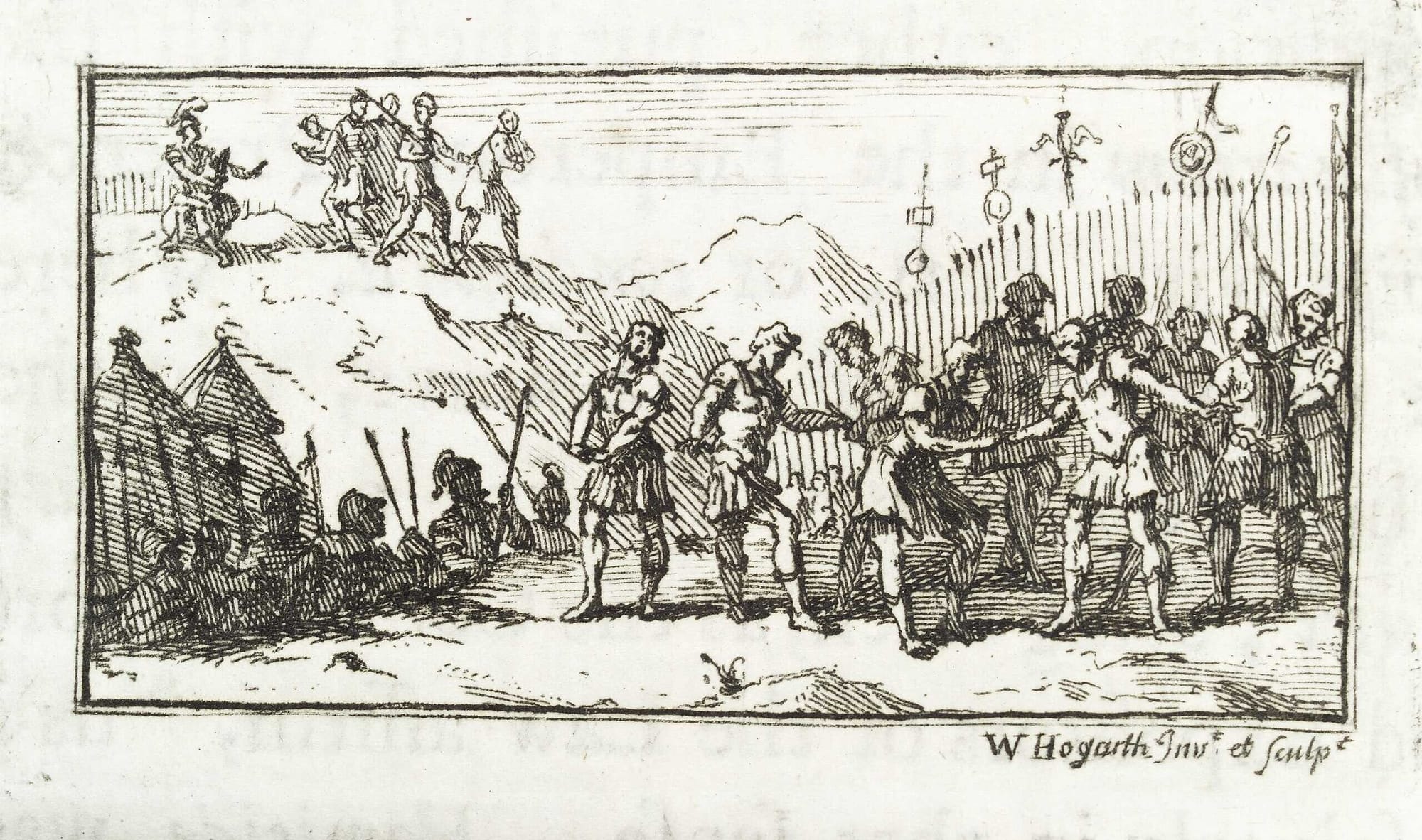

Example of the Roman military punishment of Banishment. Credits: Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0

One of the oldest penalties recorded in Roman law was aqua et ignis interdictio—the banishment from the community, symbolized by denying the offender access to water and fire. This punishment rendered a person an outcast, stripping them of citizenship and forcing them into exile. It was often reserved for the crime of perduellio (high treason), ranking just below the death penalty in severity.

Capital punishment (poena capitalis) came in many forms, each tailored to the crime and often the social status of the accused. Beheading by axe was considered the most honorable method, but others faced crucifixion, being thrown from the Tarpeian Rock, burned alive, buried while still breathing, or condemned to fight wild animals in the arena (damnatio ad bestias).

Among the most gruesome was the poena cullei, the punishment for parricide: the murderer of a father was sewn into a leather sack along with a dog, a cock, a snake, and a monkey—then cast into the water, denied even the dignity of burial.

“Those who commit capital crimes are, if from the upper classes, decapitated or exiled; those from the lower orders are crucified, burnt alive or thrown to the beasts.”

Legal manual, c. 300 AD

“The person was first whipped, or beaten, with virgis sanguinis ("blood-colored rods", probably) and his head was covered in a bag made of a wolf's hide. On his feet were placed clogs, or wooden shoes, and he was then put into the poena cullei, a sack made of ox-leather. Placed along with him into the sack was also an assortment of live animals, arguably the most famous combination being that of a serpent, a cock, a monkey and a dog. The sack was put on a cart, and the cart driven by black oxen to a running stream or to the sea. Then, the sack with its inhabitants was thrown into the water.”

19th-century historian Theodor Mommsen

The same crime might lead to exile for a senator, but crucifixion or the arena for a slave.

Imprisonment, while familiar to modern readers, played only a minor role in Rome. The Romans rarely used confinement as a sentence in itself. Instead, prisons functioned primarily as holding cells—places to detain the accused while awaiting trial or execution.

The most infamous of these was the Mamertine Prison at the foot of the Capitoline Hill. Its lower chamber, the Tullianum, was a dark, airless pit believed to have housed enemies of the state—and, according to tradition, Saint Peter himself.

When imprisonment did occur, it was often paired with forced labor (opera publica), especially in cases of life sentences. The Roman term carcer did not imply punishment as such, but custody. Two categories existed:

- Publica vincula (detention in chains)

- Publica custodia (temporary holding)

Prisons were overseen by a board of three minor officials, the triumviri capitales, and in the provinces, local authorities assumed that role.

Other penalties focused on financial loss or public humiliation. A citizen might be fined (poena pecuniaria) or see their entire estate confiscated—especially in political trials where emperors sought to punish rivals without bloodshed. For slander or betrayal of trust, a person could be placed on the pillar of shame and stripped of public rights, barred from voting, testifying, or making a legal will.

One of Rome’s most chilling institutions was proscriptio—a political weapon disguised as justice. Those declared enemies of the state had their names posted publicly. Any citizen could kill them and claim a reward: money for freemen, freedom for slaves. Even aiding a proscribed person—offering food, shelter, or money—was itself punishable by death or proscription. Over time, this practice became so controversial that it was eventually abandoned.

It’s worth noting that prison, as we understand it today, was not considered a form of punishment in Rome. It was used as a temporary measure—for debtors, the mentally ill, vagrants, or those awaiting judgment. The lack of classification within prisons, where all detainees were held together regardless of age, status, or crime, reinforces the idea that Roman incarceration was meant to restrain, not to reform.

Rome’s penal system may feel alien to modern eyes, but it functioned precisely as the Empire intended: to preserve hierarchy, display control, and root justice in the public square. What it lacked in rehabilitation, it made up for in visibility—and the message was clear. (‘System of Punishment In Roman law” by Filip Mirić, Ph.D. Associate for Post Graduate Studies, University of Niš, Serbia)

Crime in Rome was not only punished. It was performed.

Example of Beheading, a Roman military punishment carried out by the use of a axe or sword. Credits: Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0

Decimation, a military punishment, involved killing one in ten soldiers of a unit for cowardice or mutiny, underscoring the importance of discipline in the Roman military. When a cohort, consisting of approximately 480 soldiers, was subjected to decimation as a form of punishment, it was organized into groups of ten. Through a process of drawing lots, the soldier who drew the shortest straw in each group was put to death by his nine peers, typically through methods such as stoning, beating, or stabbing.

The survivors were then usually forced to subsist on barley instead of the standard wheat rations for several days and had to sleep outside the camp's protective walls for a period. Given that the selection for execution was based on chance, any soldier within a decimated group could be targeted for death, without consideration for their individual guilt, rank, or achievements.

Law and Everyday Life: How Deep Did Roman Justice Go?

The influence of Roman law on daily life across the empire depended not only on what was written in statutes and commentaries, but on how consistently the legal system could function across an extraordinarily diverse landscape. For Roman justice to take hold, it required more than imperial edicts—it needed the participation of local populations who were willing, or compelled, to adopt Roman legal forms.

In the western provinces, Roman law often accompanied the spread of Roman-style urbanism and governance. There, cities modeled on Roman institutions helped promote legal uniformity as part of cultural and administrative integration. In the east, the picture was more complex. Regions like Egypt had their own deeply rooted legal traditions, including Graeco-Egyptian law, which had long governed personal and commercial affairs.

Over time, Roman law blended with these local systems, especially after the Constitutio Antoniniana of 212 CE granted Roman citizenship to nearly all free inhabitants of the empire. The result was often a hybrid legal culture—part Roman, part regional.

This raises an important question: how much did Roman law really shape the lives of ordinary people? Some scholars argue that the Roman jurists—those responsible for refining legal principles during the imperial period—were deeply attuned to social realities.

Their writings reflect concerns about practical issues such as property leases, the legal status of sex work, and transportation infrastructure. These examples suggest that legal thought was not entirely abstract but was intended to function in the real world.

However, for Roman law to truly shape daily life, two conditions had to be met. First, legal categories—especially those defining status, such as citizen, slave, or freedman—had to matter beyond the law books.

Second, people had to trust and use Roman legal processes for core aspects of life: marriage, inheritance, business contracts, and land use. Without functioning courts and accessible procedures, even the most advanced legal doctrines would remain academic.

If people had no legal avenue to resolve disputes, they would fall back on local customs, social pressure, or violence. (Oxford Handbooks Online. "Law and Social Formation in the Roman World" edited by Michael Peachin)

In the end, Roman justice was both everywhere and uneven—visible in public punishment, but powerful only when it touched the daily choices of life, death, and legacy.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: