Cato the Younger: The Last Roman of the Republic

He did not seek the people’s love—only their attention. Cato the Younger made virtue his weapon, tradition his armor, and resistance his legacy. In a Republic seduced by power, he stood alone, unyielding.

What is virtue in the face of ruin? For Cato the Younger, it was everything. A Stoic by philosophy and unyielding by nature, he stood firm as the Roman Republic crumbled around him. In an age of shifting loyalties, civil war, and rising autocracy, Cato chose principle over power, and resistance over compromise.

To his allies, he was the conscience of the Republic; to his enemies, an obstacle to unity. But to posterity—through the words of Cicero, the poetry of Lucan, and the example of his own death—Cato became something greater than a man. He became the last Roman of the Republic.

Virtue Without Power in Sallust's Republic

The Roman historian Sallust witnessed firsthand the slow unraveling of the Republic in the final years of the first century BCE. Among the many towering personalities who defined this tumultuous era, Sallust made a remarkable claim: that Gaius Julius Caesar and Marcus Porcius Cato were the two most virtuous Romans of living memory.

That Caesar should be singled out is expected—his political and military career was unparalleled, his name became synonymous with imperial power. But what makes Sallust's comparison striking is that he placed Cato on equal footing, despite Cato's lack of military commands, high office, or popular legacy. As Sallust famously wrote:

"But within my own memory there have been two men with exceptional virtue, albeit with differing characters: M. Cato and C. Caesar…

Their birth, age, and eloquence were very nearly the same, they had the same greatness of spirit, and their glory was evenly matched, although different to each.

Caesar was held to be great because of his benefactions and munificence, but Cato for the integrity of his life.

The first became famous for his mildness and mercy, while severity added distinction to the latter.

Caesar obtained glory through his giving, his assisting, and his pardoning, while Cato achieved this by engaging in no amount of bribery.

The one was a shelter for those suffering, while the other was a bane for evil-doers.

The courtesy of the first was praised, but the constancy of the second... He preferred to be good rather than to seem good, and so the less he sought glory, the more it attended on him."

Sallust's evaluation may strike the modern reader as unusual. Cato lacked many of the traditional measures of power in Roman political life. He never reached the consulship, did not command armies, had no great fortune or extensive client base, and often frustrated his allies as much as his enemies.

Yet Cato stood as Caesar’s equal in Sallust's eyes because he exemplified an unyielding, almost radical embodiment of Roman virtue.

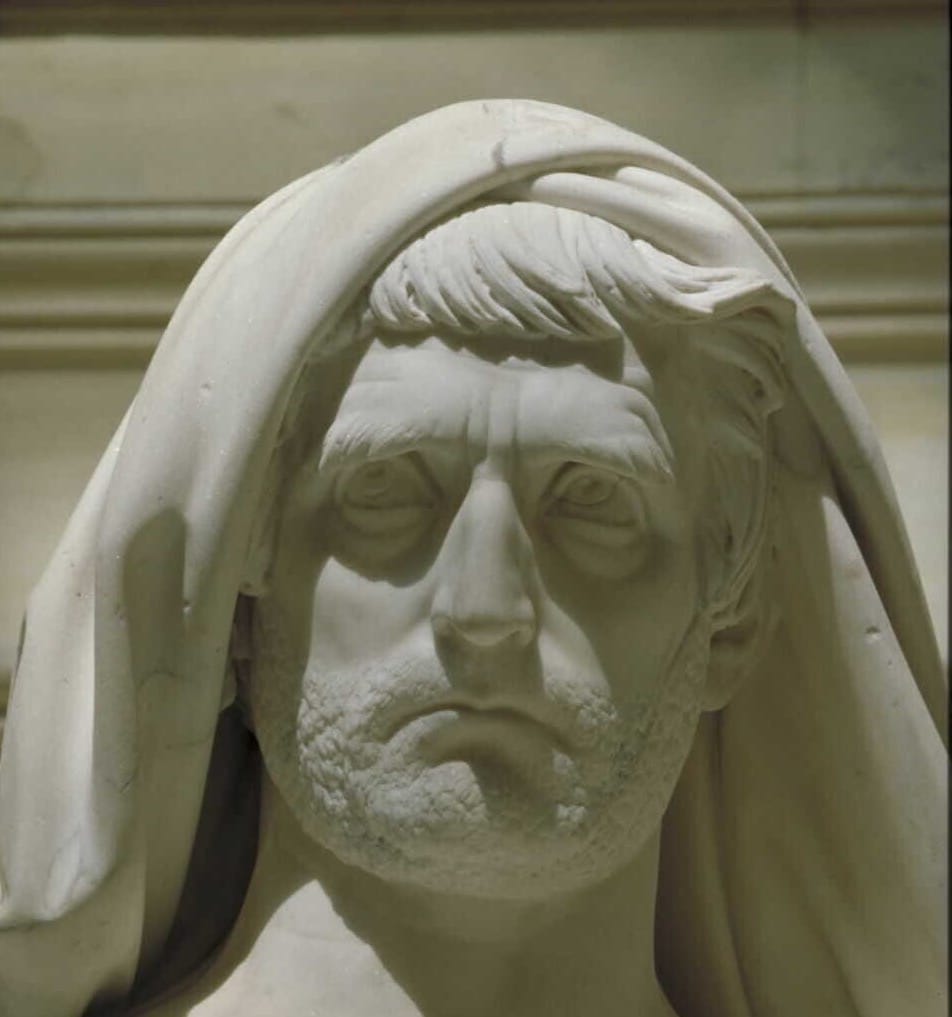

A closeup of Cato the Younger’s statue from the Louvre. Credits: 1996 Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Pierre Philibert

Cato's influence came not from traditional avenues of command but from his calculated manipulation of tradition. Romans deeply revered their ancestors and customs, and senators were especially dependent on claims of continuity with Rome's noble past.

Cato made himself into a symbol of these ancestral values—not through birth or wealth, but through behavior. He adopted old-fashioned habits, dress, and speech, projecting the image of a man rooted in the Republic's earliest, most virtuous days. Whether these practices were authentic revivals or stylized inventions, they worked. Cato's deliberate archaism cast a powerful spell over a Senate desperate for symbols of legitimacy.

But the power of that image had limits. Cato's extreme conservatism often alienated voters who respected tradition but did not want to return to a mythical past. His inflexible commitment to what he believed the mos maiorum (ancestral custom) demanded often placed him at odds with public opinion and even his fellow senators.

While many admired him, few followed him into political danger. Though he united senators in moments of crisis, his uncompromising style repeatedly undermined more pragmatic attempts at consensus.

Still, Cato was a force in Roman politics. Without military power or high office, he exerted influence through moral authority. He helped block Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus at key moments, undermining their efforts to dominate the Senate. He opposed the First Triumvirate, fought reforms he saw as corrupt or demagogic, and pushed the Republic toward civil war by rejecting compromise with Caesar.

He was not solely responsible for the Republic's collapse, but he was essential in shaping the conditions that made it possible.

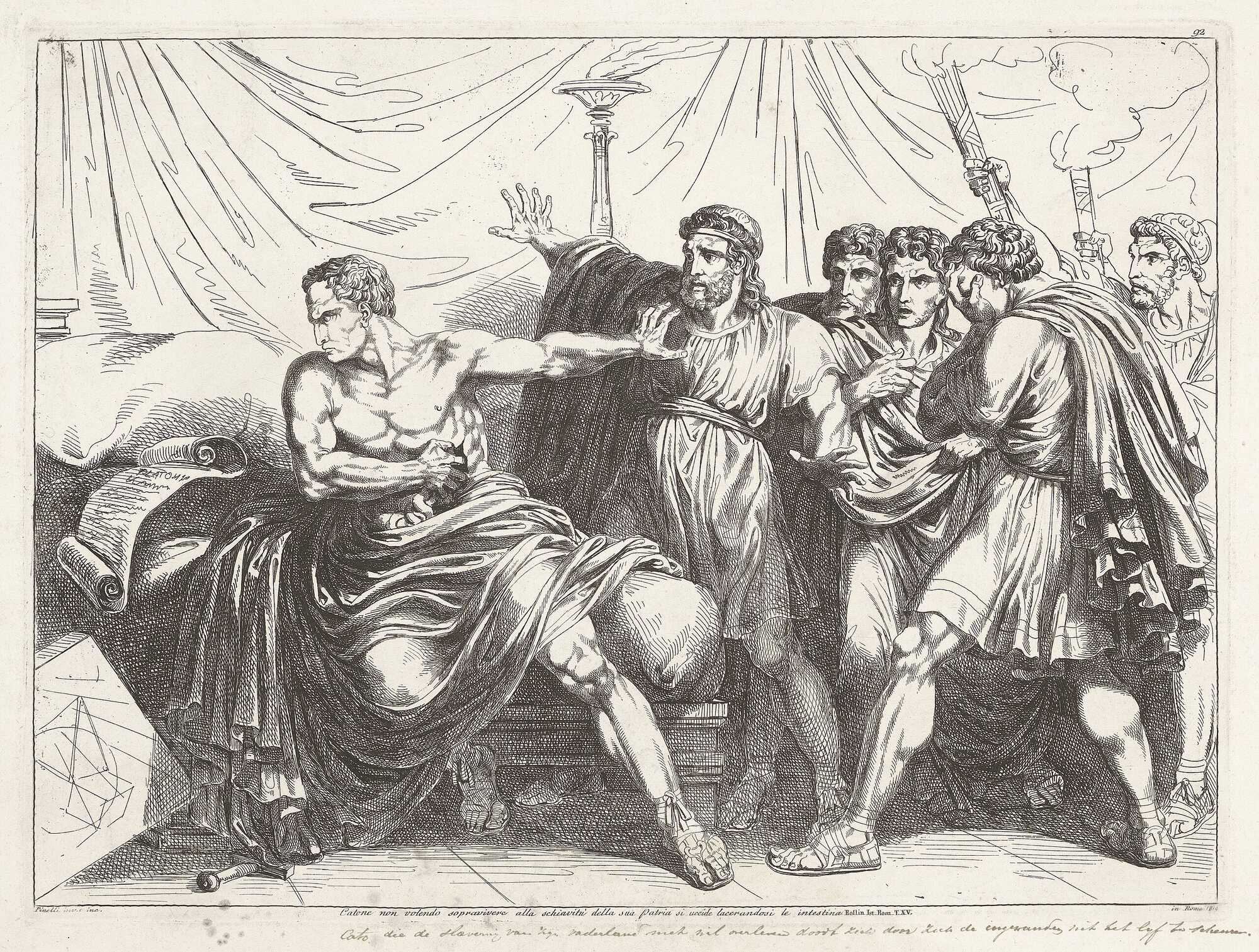

Johann Heinrich Tischbein’s painting of Cato the Younger reading Plato’s Phaedon before his death. Public domain

Cato’s methods reveal how Roman tradition could be repurposed into political strategy. He built a career as a living symbol of Roman virtue and liberty, and while he could wield this identity to great effect, it also exposed the fragility of such appeals.

Roman voters respected liberty but still supported Caesar when it suited their interests. Senators admired ancestral virtue but often preferred expedience. Cato embodied the tension between Rome’s ideals and its political realities.

He also reminds us how personal Roman politics could be. Cato opposed Caesar long before Caesar acted like a dictator. During the Catilinarian Conspiracy, he falsely tried to implicate Caesar in treason, which could have led to Caesar’s execution.

Whether motivated by foresight or personal hostility, Cato's actions helped drive Caesar into opposition to the Senate. His feud with Caesar—possibly more personal than principled—contributed to the dynamics that led to civil war.

Understanding Cato means understanding how ideas of virtue, liberty, and tradition were used in Roman politics. Cato's austerity and moralism made him a symbol of resistance, even if they often limited his practical effectiveness. His opposition to Caesar was framed in cultural terms: freedom versus tyranny. But as Sallust’s nuanced portrayal shows, this wasn't a clash of good and evil—it was a contest between two very different kinds of Roman greatness.

After his suicide at Utica in 46 BCE, Cato became more than a man: he became a myth. Later writers, especially Plutarch, reimagined him as a Stoic martyr. His death was recast as a philosophical stand for liberty, likened to that of Socrates.

But the historical Cato was not a Greek sage—he was a Roman senator, fierce, inflexible, and deeply embedded in the political culture of his time. His legacy was shaped as much by his enemies and admirers as by his own actions.

In the end, Sallust was right. Cato's virtue, though austere and sometimes self-defeating, made him one of the central figures of the Republic's last days. He did not command armies or write laws that endured, but he fought, in his way, for a Republic he believed still could be saved. He may not have won—but his integrity was his triumph. (Cato the Younger: Life and death at the end of the Roman Republic, by Fred K. Drogula)

A Stoic’s Calculated Distance

Though often remembered as an unyielding Stoic and principled senator, Cato the Younger’s relationship with the Roman people was more complex than later legend admits. Cato did not avoid popular assemblies (contiones) nor shrink from dramatic public gestures—in fact, he often used them deliberately to reinforce his austere brand.

Cato’s early acts as quaestor, particularly his rigorous oversight of the treasury and prosecution of corruption, earned him admiration for integrity if not affection. As tribune in 62 BC, he even proposed an expansion of the grain dole—an act of political pragmatism designed to calm public anger after the executions of the Catilinarian conspirators.

Yet when another tribune, Metellus Nepos, sought to recall Pompey, Cato resorted to obstruction and confrontation, physically blocking the measure. Theatrics became a tool in his arsenal: he filibustered in the Forum, shouted from the rostra, claimed thunder had disrupted proceedings, and even allowed himself to be dragged to prison as a statement of resistance.

Far from courting popularity, Cato's gestures aimed at protecting what he viewed as the res publica, often against figures like Caesar and Pompey whom he considered tyrannical. He rarely flattered the crowd. He refused to canvass for the consulship and appeared in public barefoot and without a tunic—a symbol of his disdain for electoral theatrics.

Yet, he knew how to make the people look and listen when it served his cause. During aedilician games, for instance, he handed out vegetables and firewood instead of lavish prizes—and the people loved it.

Cato’s relationship with the Roman people, then, was strategic, not sentimental. He was not a man of the people, but a man who understood how to use them. His ultimate loyalty lay not with the crowd, but with a stern vision of the Republic: a Rome steered by incorruptible senators and guided by virtue, not applause.

Cato Against Caesar and Pompey

Cato the Younger’s political life was defined by relentless resistance to what he saw as creeping tyranny—embodied most clearly in Pompey and Caesar. From the early 60s BC, Cato opposed Pompey’s attempts to consolidate power, blocking proposals to grant him extraordinary commands or to delay consular elections for his benefit. He famously rejected Pompey’s offer of a marriage alliance and denounced him as a privatus dictator—a private citizen behaving like an autocrat.

His opposition to Caesar was no less dramatic. In 59 BC, when Caesar attempted to pass his agrarian law, Cato filibustered so persistently that Caesar ordered him dragged off to prison—either from the Senate or the rostra, depending on the source. Cato responded by turning the moment into political theatre, calling on the crowd for help and transforming the episode into a performance of principled defiance.

He used obstruction, shouting, even spurious religious omens to delay proceedings—he once claimed to have heard thunder to stop the lex Trebonia that handed consular provinces to Pompey and Crassus. He wasn’t above spectacle, but it was always for the sake of the res publica as he understood it.

Cato’s efforts failed to block the dynasts, but they defined his public identity. He was no friend of the people’s idols—and he paid the price. Pompey’s camp sabotaged Cato’s electoral run for the praetorship in 55 BC, and although he eventually gained office, he remained politically isolated. Still, he continued his campaign for a Republic untainted by ambition, using every legal and rhetorical tactic available to him.

The Death of Cato: More than a Gesture

Cato’s final act—his suicide at Utica in 46 BC—cemented his posthumous image as the last true Roman republican. This powerful gesture may have distorted how we view his political life. Later admiration for Cato as a martyr of liberty can overshadow the strategic, pragmatic, and at times theatrical politician he actually was.

What his suicide proves, more than anything, is that he was not simply a cynic or a power-seeker playing at virtue. If his sole aim had been political influence, he could have survived defeat and negotiated a place in Caesar’s new order.

But Cato’s death was consistent with the life he had lived—rooted in Stoic conviction, loyalty to an idealized res publica, and a refusal to bow to a would-be autocrat. His principled exit was the culmination of decades of effort to align rhetoric, public persona, and political action under a single moral code.

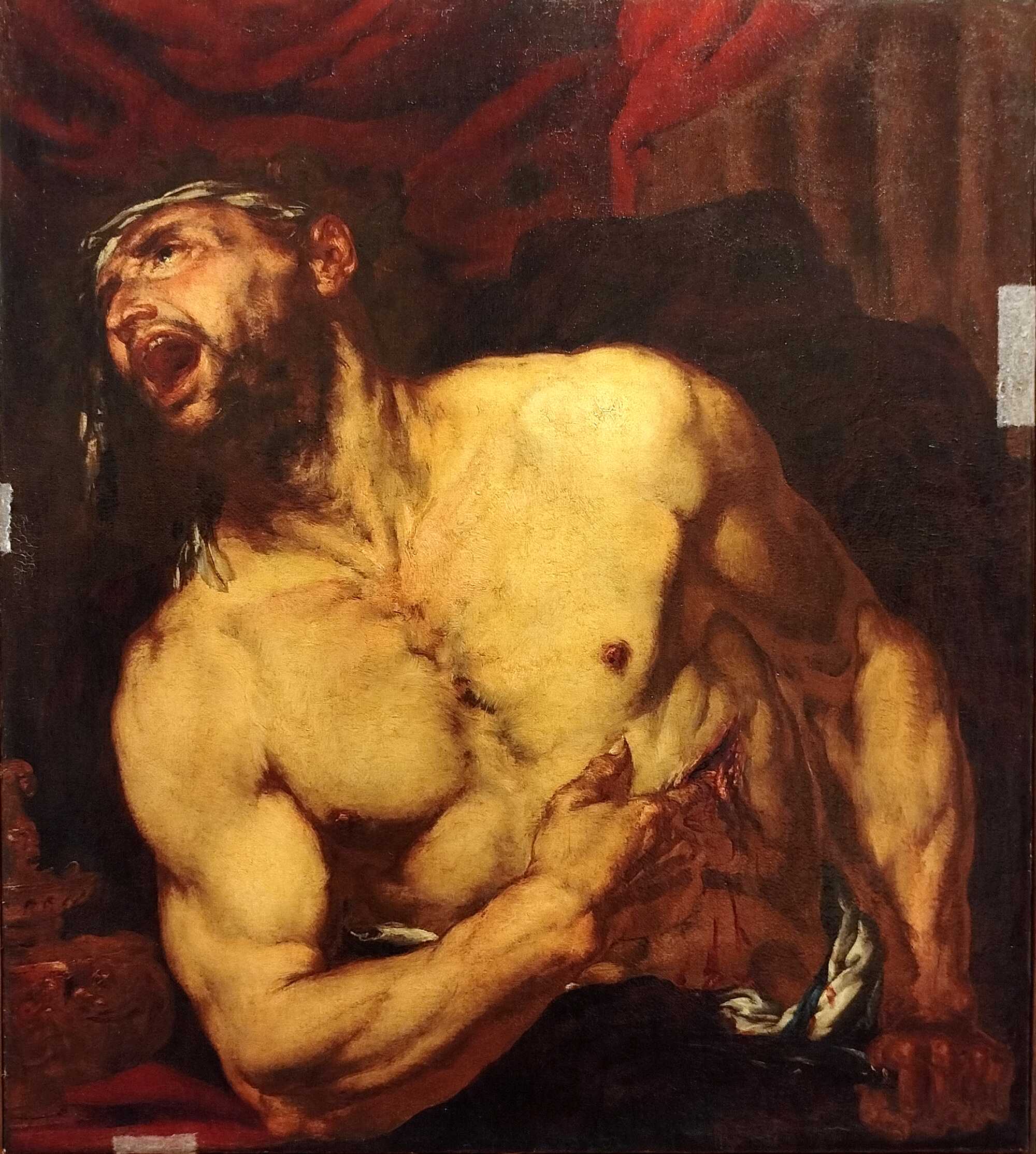

Painting #1: Giovanni Battista Langetti

Painting #2: Giovanni Battista Langetti

Painting #3: Giovanni Battista Langetti

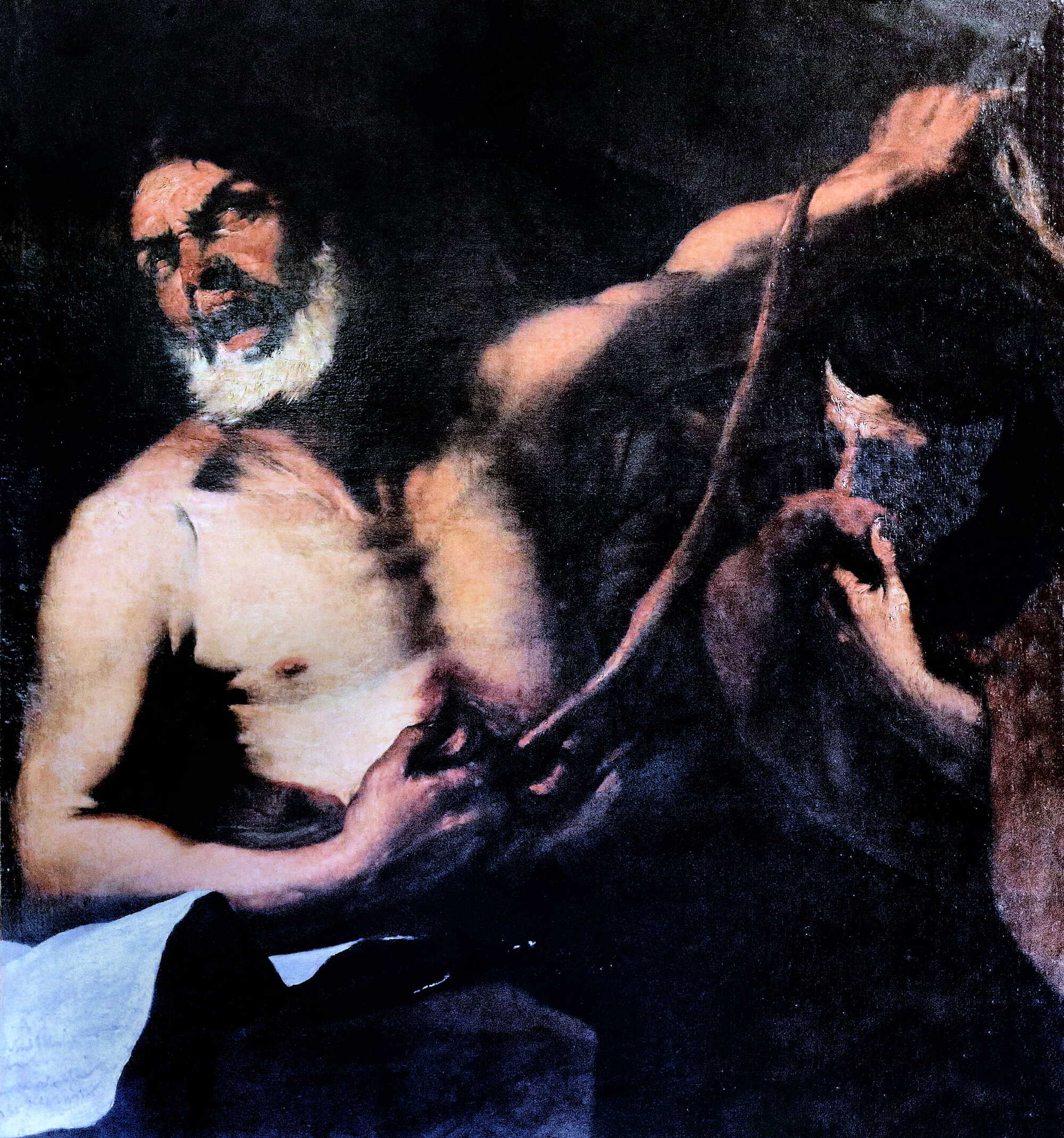

Painting #4: Luca Giordano

Painting #5: Johann Carl Loth

Ιmages 1, 2, 3, 5: Public domain

Image 4: jean louis mazieres, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In life, Cato may not have been the people’s darling, nor always effective. But in death, he became a symbol whose legacy outlived even the Republic he had tried to preserve. (Cato and the People, by Henriette van der Blom)

“…Cato drew his sword from its sheath and stabbed himself below the breast.

His thrust, however, was somewhat feeble, owing to the inflammation in his hand, and so he did not at once dispatch himself, but in his death struggle fell from the couch and made a loud noise by overturning a geometrical abacus that stood near.

His servants heard the noise and cried out, and his son at once ran in, together with his friends.

They saw that he was smeared with blood, and that most of his bowels were protruding, but that he still had his eyes open and was alive; and they were terribly shocked.

But the physician went to him and tried to replace his bowels, which remained uninjured, and to sew up the wound.

Accordingly, when Cato recovered and became aware of this, he pushed the physician away, tore his bowels with his hands, rent the wound still more, and so died.”

Plutarch, The life of Cato the Younger

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: