Arausio: The Defeat That Reshaped Roman Power

The defeat at Arausio in 105 BCE was more than a battlefield disaster. It exposed deep fractures in Roman command, reshaped military power, and left a psychological legacy that influenced Roman responses to crisis for generations.

In 105 BCE, somewhere along the Rhône near Arausio, a Roman army confronted a threat it believed it could manage. What followed did not immediately enter Rome’s memory as a turning point, but as an unsettling rupture—confusing, humiliating, and difficult to explain. Reports arriving in the city spoke not only of defeat, but of disorder, disagreement, and authority breaking down at the highest level. Arausio would come to matter not because of a single decision or moment on the field, but because it revealed vulnerabilities the Republic had long preferred not to see.

Arausio and the Shock of the Northern Wars

The defeats inflicted by the Cimbri and Teutones, culminating in the catastrophe at Arausio in 105 BCE, marked a fundamental rupture in Roman perceptions of security. For the first time since the Gallic sack of Rome, the Republic confronted enemies perceived as both unfamiliar and existential, emerging from regions beyond Rome’s geographical and cultural imagination.

Ancient authors consistently framed these wars as something more than conventional military setbacks: they described them as overwhelming, sudden, and deeply unsettling events that challenged Rome’s sense of control over its world.

The language used by later writers reveals how these defeats were remembered not merely as losses, but as collective shocks. Roman commanders involved in the disasters were routinely ridiculed and blamed, serving as convenient scapegoats for a crisis that appeared to exceed individual responsibility.

Plutarch explicitly frames the Cimbri and Teutones as an existential, destabilising shock, not a routine war:

“The terror occasioned by these nations was greater than any that had ever before seized Rome, except that of the Gauls. For they were a people unknown, of vast numbers, and their movements were rapid and resistless.” (Marius 11.2)

And again, emphasising panic and loss of control:

“Italy was filled with confusion and fear, expecting daily that the barbarians would descend upon it.” (Marius 13.1)

This language directly supports suddenness, scale, and collective fear.

Caesar shows that this fear was still active memory, not retrospective exaggeration. When describing the Helvetii and their allies, he deliberately invokes earlier trauma:

“The memory of the disaster suffered by the Roman people at the hands of the Cimbri and Teutones was still fresh.” (De bello Gallico 1.7)

He reinforces this by recalling the defeat of Cassius Longinus (linked to Cimbrian allies):

“This defeat was the more bitter because it reminded them of the ancient calamity.” (De bello Gallico 1.14)

At the same time, extraordinary political responses followed. The repeated election of Gaius Marius to the consulship—five times in rapid succession between 104 and 100 BCE—reflected widespread loss of confidence in the traditional elite and a readiness to abandon established norms in favour of perceived effectiveness. Emergency measures such as the declaration of a tumultus further underline the sense that Rome believed itself under immediate and exceptional threat.

Although Marius eventually neutralised the danger through decisive victories, the psychological impact of the Cimbrian and Teutonic wars proved remarkably durable. Memories of the invasion lingered for generations, shaping how Romans interpreted later encounters with northern peoples. Julius Caesar deliberately activated these associations in his Gallic campaigns, repeatedly invoking earlier defeats and framing new enemies in ways that echoed the terror once inspired by the Cimbri and Teutones.

Even defeats that predated his birth were treated as part of a shared, living memory, suggesting how deeply embedded these events remained in Roman consciousness.

This legacy persisted into the imperial period. Augustus explicitly connected his regime to the suppression of northern threats, carefully reviving the memory of earlier crises to reinforce his image as restorer and protector. Later panics—after Teutoburg, during rumours of German unrest, or under emperors as late as Caligula—were repeatedly framed through the same historical lens. The fear that Germanic forces might once again pour into Italy was not rhetorical invention, but a reflex rooted in long-standing recollection.

Seen in this light, Arausio was not simply a military disaster but a formative episode in Rome’s collective memory. It established a template for interpreting northern threats, justified extraordinary political adaptations, and left a residue of anxiety that shaped Roman reactions to crisis for more than a century.

Persistent Anxiety on the Rhine after Caesar

In the decades following Caesar’s withdrawal from Gaul, large-scale warfare with German tribes temporarily subsided, but Roman anxiety did not. Evidence from political correspondence, poetry, and later historical reflection shows that the Rhine frontier continued to provoke unease, especially in moments of internal instability. Only weeks after Caesar’s assassination, Cicero voiced concern about the situation in the north, a fear eased only when reports arrived that German communities had sent envoys pledging obedience to Roman commanders. The speed with which such reassurance was sought and recorded reveals how readily the spectre of German unrest resurfaced in Roman political thinking.

“That the Germans and those tribes, on hearing of Caesar’s death, sent envoys to Aurelius, who had been placed in command by Hirtius, promising to carry out his orders.” (Cicero, Letters to Atticus 14.9.2)

Cicero’s relief is implicit in the report itself. The mere fact that he felt reassured by news of German envoys pledging obedience shows how real the fear of northern unrest was in the immediate aftermath of Caesar’s murder. The Rhine frontier appears here not as an active war zone, but as a latent threat capable of compounding Rome’s internal crisis—precisely the kind of anxiety later writers would amplify when recalling Arausio, the Cimbri, and subsequent German defeats.

This apprehension also entered literary culture. In the Georgics, Virgil depicted Germania as a land where the clash of arms filled the sky and war lay perpetually close to waking—imagery that resonates with the uncertainty following Caesar’s death. These poetic signals were grounded in reality.

During the 30s and 20s BCE, German groups repeatedly crossed the Rhine, prompting Roman military responses. Marcus Agrippa led operations east of the river in 39/38 BCE, while subsequent commanders confronted coalitions involving the Treveri and powerful German peoples such as the Suebi, whom ancient geography described as surpassing others in strength and numbers.

Under Augustus, these frontier tensions acquired lasting political meaning. The defeat suffered by Marcus Lollius at the hands of German forces proved psychologically significant enough to echo through Augustan propaganda and poetry. Augustus later highlighted the submission of German leaders—especially the Sugambri—in his Res Gestae, a selective emphasis that suggests how deeply the episode resonated.

Contemporary poets repeatedly singled out the Sugambri as emblematic of the German threat, forecasting or celebrating their subjugation in the aftermath of Lollius’ defeat.

Within this climate, blame followed trauma. Lollius appears to have borne personal responsibility for the disgrace, disappearing from major military commands as responsibility for German warfare passed to Drusus. Although later sources hint at attempts to rehabilitate his reputation, the silence surrounding his subsequent career suggests that the Rhine defeat carried real consequences.

The episode illustrates how, long after Caesar, incursions from beyond the Rhine continued to stir fear, shape memory, and influence political fortunes at Rome. (“A real Roman defeat: memory, collective drama and the clades Lolliana” by Bernt Kerremans)

Arausio and the Scale of Catastrophe

The Battle of Arausio, fought on 6 October 105 BCE near Arausio, pitted Roman Republican forces against the combined strength of the Cimbri and Teutones. The outcome was one of the most devastating defeats Rome ever suffered. Ancient figures, attributed to Livy, place Roman losses at roughly 120,000 dead—exceeding even the tolls of Cannae and Carrhae.

The disaster left the Alpine approaches exposed and Italy itself seemingly open to invasion, a danger avoided only because the victorious tribes turned their attention elsewhere.

Despite its scale, Arausio occupies a marginal place in popular and even scholarly memory. The surviving ancient evidence for the battle and the wider Cimbrian War is fragmentary, forcing modern historians to rely on scattered references rather than continuous narrative. As a result, Arausio is often treated primarily as a prelude: a necessary backdrop for the repeated consulships of Gaius Marius and for the military reforms traditionally associated with his rise.

Among modern reconstructions, the most influential remains that of Theodor Mommsen, whose nineteenth-century history of Rome offers a concise but carefully reasoned account of the battle and its context. Building on Livy’s testimony and Mommsen’s outline, recent scholarship has sought to reconstruct not only the engagement itself but also the political tensions, command failures, and strategic misjudgements that preceded it.

Central to these analyses is the argument that Arausio was not simply the result of barbarian strength, but of Roman leadership breakdown—an internal failure with consequences as grave as any external threat.

A Republic Under Strain and a New Northern Threat

In the decades leading up to Arausio, Rome was already under intense internal and external pressure. From the 130s BCE onward, tensions between the aristocracy and the lower orders had sharpened, as repeated attempts to broaden political and economic rights met entrenched resistance. This unresolved conflict shaped the political atmosphere of the period and influenced the behaviour of Rome’s governing class, including the senior commanders who would later confront disaster on the Rhône.

Beyond Italy, Rome had only just concluded a series of demanding wars. The capture of Numantia in 133 BCE secured much of Celtiberia, while the suppression of the Sicilian slave uprising followed almost immediately. Hardly had these conflicts ended when Rome became embroiled in the war against Jugurtha in Numidia in 112 BCE—a campaign prolonged by Jugurtha’s resilience and duplicity, and still unresolved at the time of Arausio. Roman attention and resources were already stretched thin.

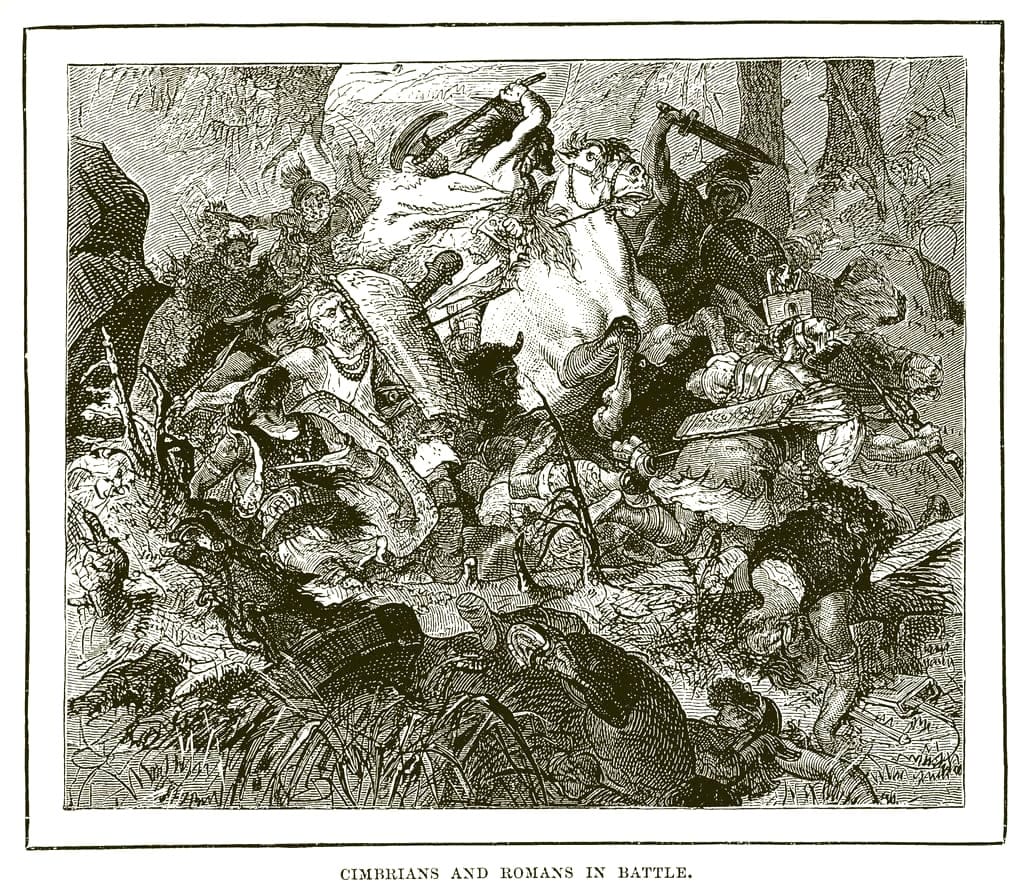

While Rome was preoccupied, a far more destabilising movement was unfolding north of the Alps. The Cimbri, originating in the Jutland peninsula, and the Teutones from northeastern Germany began moving south in large numbers. Displacement, likely driven by demographic pressure, pushed the Cimbri across Germanic and Gallic territories, where they joined forces with the Teutones and smaller groups.

Rather than a conventional raiding force, ancient and modern observers alike understood this as a migrating population seeking new land, accompanied by families, possessions, and livestock.

This character distinguished the threat they posed. The Romans were confronted not with a typical predatory expedition, but with an entire people in motion, intent on resettlement as much as plunder. Cultural descriptions in the sources emphasise practices that heightened Roman unease: ritualised displays of courage, aggressive battlefield taunts, and a warrior ethos that prized death in combat.

Arausio was not Rome’s first encounter with these groups, nor its first humiliation. In 113 BCE, at Noreia, Roman forces under the consul Gnaeus Papirius Carbo attempted to manage a Cimbrian incursion into Tauriscan territory. Although the Cimbri initially complied with Roman demands to withdraw, Carbo’s attempt to ambush them through deception ended in catastrophe. The Roman army was routed, suffering heavy losses at the hands of an enemy it had underestimated.

Despite this defeat, Roman confidence remained largely intact. Early reverses against foreign enemies were not unprecedented, and the northern tribes were still viewed as inferior adversaries. Instead of advancing into Italy, the migrating groups turned west and south through Gaul—setting the stage for the far greater disaster that would follow at Arausio.

Commanders, Kings, and a Fractured Chain of Authority

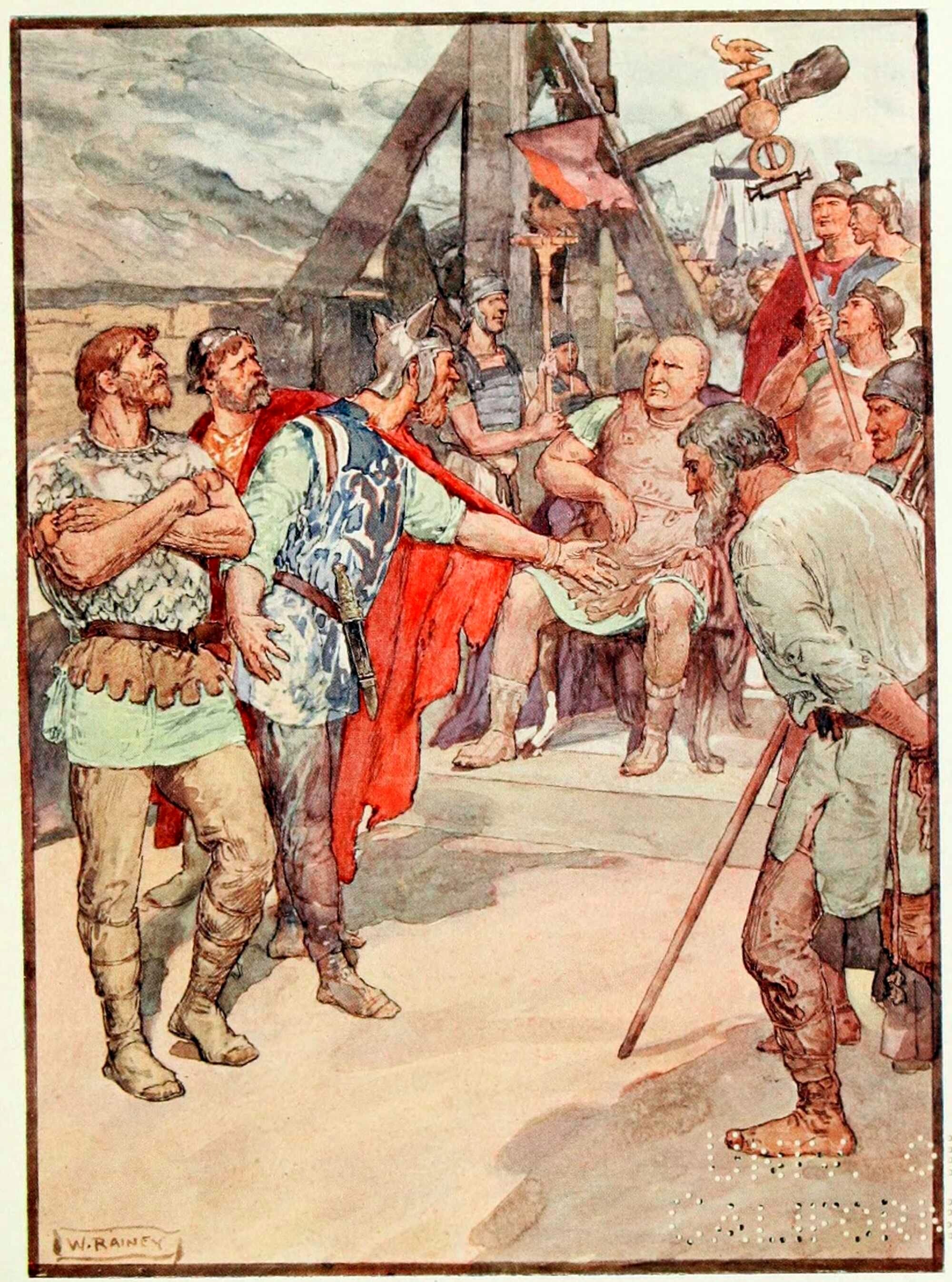

At Arausio, leadership on both sides was limited in number but decisive in consequence. Among the migrating tribes, the Cimbri were led by Boiorix, while the Teutones followed Teutobod. The sources suggest Boiorix held the dominant position, reflecting the greater size and prominence of the Cimbri. He appears more frequently in the tradition, notably in dealings with Roman envoys and in attempts at negotiation before the battle.

Roman command was far more complex—and far more dysfunctional. The forces were divided between Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, consul for 105 BCE, and Quintus Servilius Caepio, the proconsul of Cisalpine Gaul. Their relationship was marked by hostility rather than cooperation.

Caepio, a patrician and former consul, was notorious for arrogance and corruption, most famously associated with the looting of Tolosa and the disappearance of its vast treasure. His refusal to cooperate with Mallius, whom he despised as a novus homo, played a central role in the Roman collapse.

Mallius himself remains an obscure figure, known primarily for his office. As a “new man,” he lacked aristocratic backing and was treated with open contempt by Caepio. More experienced commanders were available. Publius Rutilius Rufus, Mallius’ senior colleague and a veteran of both the Numantine and Jugurthine wars, was passed over for command.

The reasons are unclear, but the sources suggest that the Germanic threat was underestimated and that Arausio was not initially regarded as a crisis requiring Rome’s most capable leadership.

Also present was Marcus Aurelius Scaurus, serving as legate to Mallius. A former consul suffectus with experience in Gallic affairs, Scaurus was tasked with reconnaissance. His force was overwhelmed early in the fighting, and his death removed one of the few experienced officers from the field.

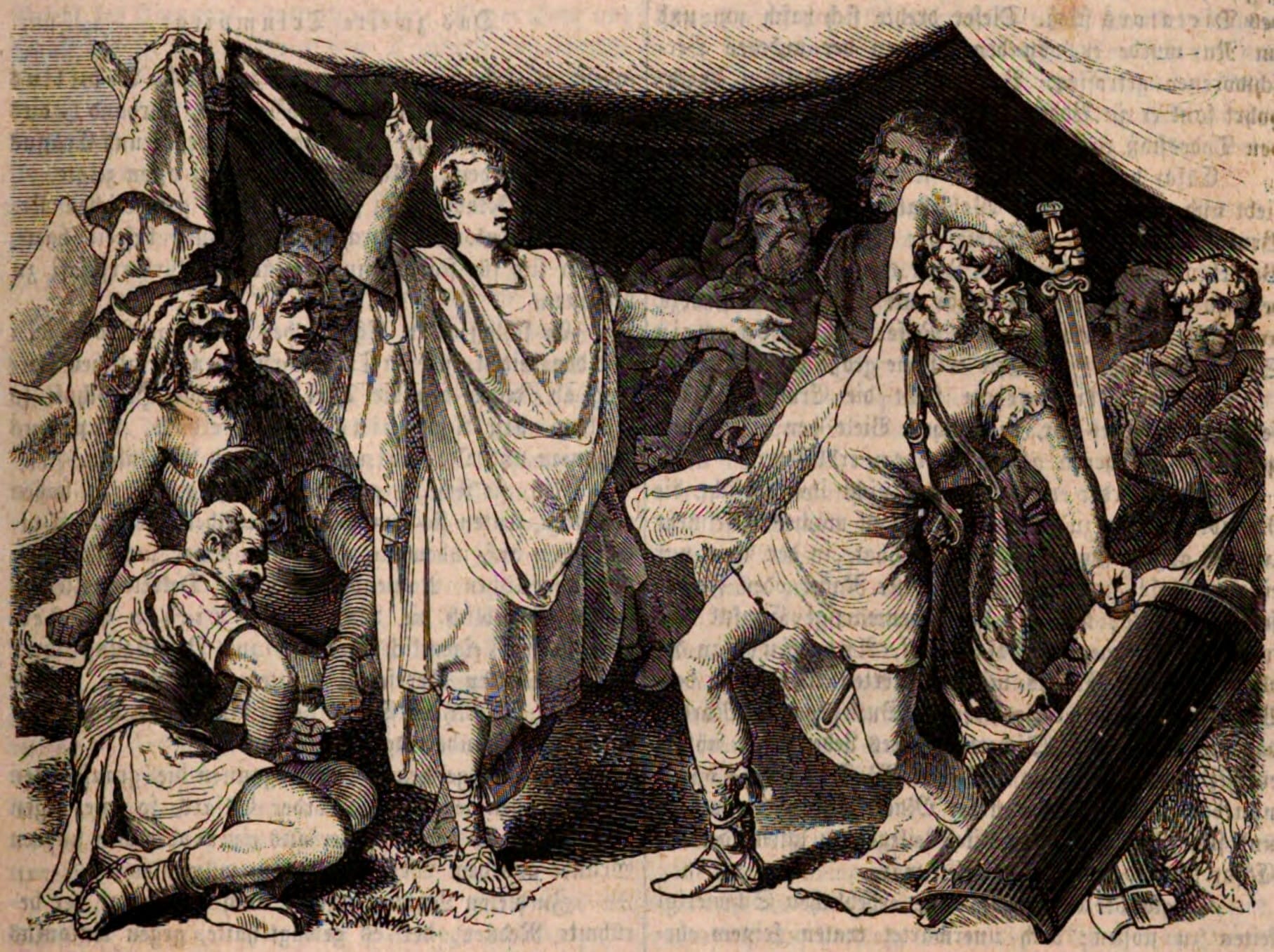

Finally, Gaius Marius hovered in the background of events. At the time of Arausio he was campaigning in Numidia and had already taken steps toward expanding recruitment by ignoring traditional property qualifications. However, his reforms were not yet fully implemented, and he played no direct role in the battle itself. It was only after the annihilation at Arausio that Marius emerged as the figure Rome turned to in order to restore military stability.

In sum, Arausio brought together fragmented Roman command, personal rivalry, and social prejudice at the highest level—conditions that proved as destructive as the enemy facing them.

Arausio, 105 BCE: Division, Disaster, and the Road to Reform

Ancient Arausio—modern Orange in southern France—stood on fertile ground along the left bank of the Rhône, a region shaped by floodplains, gentle rises, and waterways feeding into the river. Although the precise topography of the battlefield cannot be reconstructed with certainty, the surrounding landscape suggests open, low-lying terrain broken by minor streams and wooded patches, typical of the Rhône valley.

The engagement took place on 6 October 105 BCE, in the immediate vicinity of the settlement, though the town itself appears not to have played a central role in the fighting.

Rome confronted the migrating Cimbri and Teutones with two separate armies. One was commanded by the consul Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, the other by the proconsul Quintus Servilius Caepio. Personal rivalry proved fatal. Caepio, a patrician, refused to cooperate with Mallius and the two forces established camps on opposite sides of the river rather than forming a unified position. This division left the Roman armies tactically exposed from the outset.

A reconnaissance detachment led by Marcus Aurelius Scaurus advanced ahead of the main force and was quickly overwhelmed by a Cimbrian war band. Captured and brought before the Cimbrian king Boiorix, Scaurus reportedly warned against crossing the Alps and challenged the notion that Rome could be defeated. His defiance ended in execution. Only after news of Scaurus’ death did Caepio agree to cross the river—but even then he refused to merge camps or coordinate strategy with the consul.

Movements within the Roman lines appear to have unsettled the Cimbri, prompting Boiorix to signal a willingness to negotiate. Mallius was receptive. Caepio was not. Fearing that diplomacy would credit his rival, the proconsul launched an independent and hastily organised attack on the Cimbrian position. The assault failed catastrophically. Caepio’s forces were repelled, then destroyed in a counterattack, and his camp was overrun and looted.

Emboldened by their success, the Cimbri abandoned any thought of negotiation and turned against Mallius’ army. Already demoralised by internal discord and the rout of Caepio’s troops, the consul’s men collapsed under the assault. Trapped between the enemy and the river, many attempted to escape by swimming the Rhône in full equipment.

Large numbers drowned. Others were cut down alongside camp followers and non-combatants. Ancient tradition placed the losses at around eighty thousand soldiers and forty thousand auxiliaries and servants—a figure that conveyed the scale of the catastrophe, regardless of its statistical precision.

The defeat left the Alpine approaches to Italy undefended and triggered panic in Rome. Memories of earlier invasions resurfaced, and the Republic responded by turning to Gaius Marius. He was entrusted with rebuilding the army and, drawing on earlier measures as well as his own innovations, reshaped Rome’s military system.

Recruitment was widened beyond property-owning citizens, equipment was standardised and issued by the state, tactical organisation shifted from maniples to cohorts, and legions became permanent formations. These changes transformed Rome’s forces from a seasonal militia into a professional standing army.

The Cimbri and Teutones did not exploit their victory immediately. They divided their forces, buying Rome time. Marius used the respite to train his new legions and ultimately destroyed the Teutones at Aquae Sextiae in 102 BCE and the Cimbri at Vercellae in 101 BCE, ending the Cimbric War.

The aftermath of Arausio was unforgiving. Caepio was condemned, stripped of his property, and expelled from public life. Mallius was likewise disgraced. The Teutones vanished from the historical record after their defeat; the Cimbri were annihilated in Italy, with only traces of their name lingering generations later in the north. Marius emerged as Rome’s saviour, celebrated for rescuing Italy and reshaping its armies, though his later career would entangle him in the political conflicts that undermined the Republic itself.

The disaster at Arausio thus marked a turning point. It exposed the lethal consequences of aristocratic rivalry and divided command, accelerated the professionalisation of the Roman army, and altered the balance between military power and the state. The battle did not merely destroy two armies; it reshaped Rome’s relationship with war, leadership, and authority. ("Disaster at Arausio: Lessons in Leadership in the Roman Army" by Abhimanyu “Manu” Trikha, ‘14. Faculty Mentor: COL Rose Mary Sheldon, Ph.D., Department of History)

Arausio was not remembered simply because Rome lost an army. It endured because it exposed how fragile Republican authority had become when rivalry, social division, and personal ambition replaced coordinated command. The disaster accelerated changes already underway, reshaping Rome’s military system and altering the relationship between generals, soldiers, and the state. Long after the battlefield was silent, Arausio continued to shape how Romans understood fear, leadership, and the cost of failure—its consequences reaching far beyond the Rhône and deep into the future of Roman power.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: