Why did the Romans kill Jesus?

What was the real reason behind the execution of Jesus by the Romans?

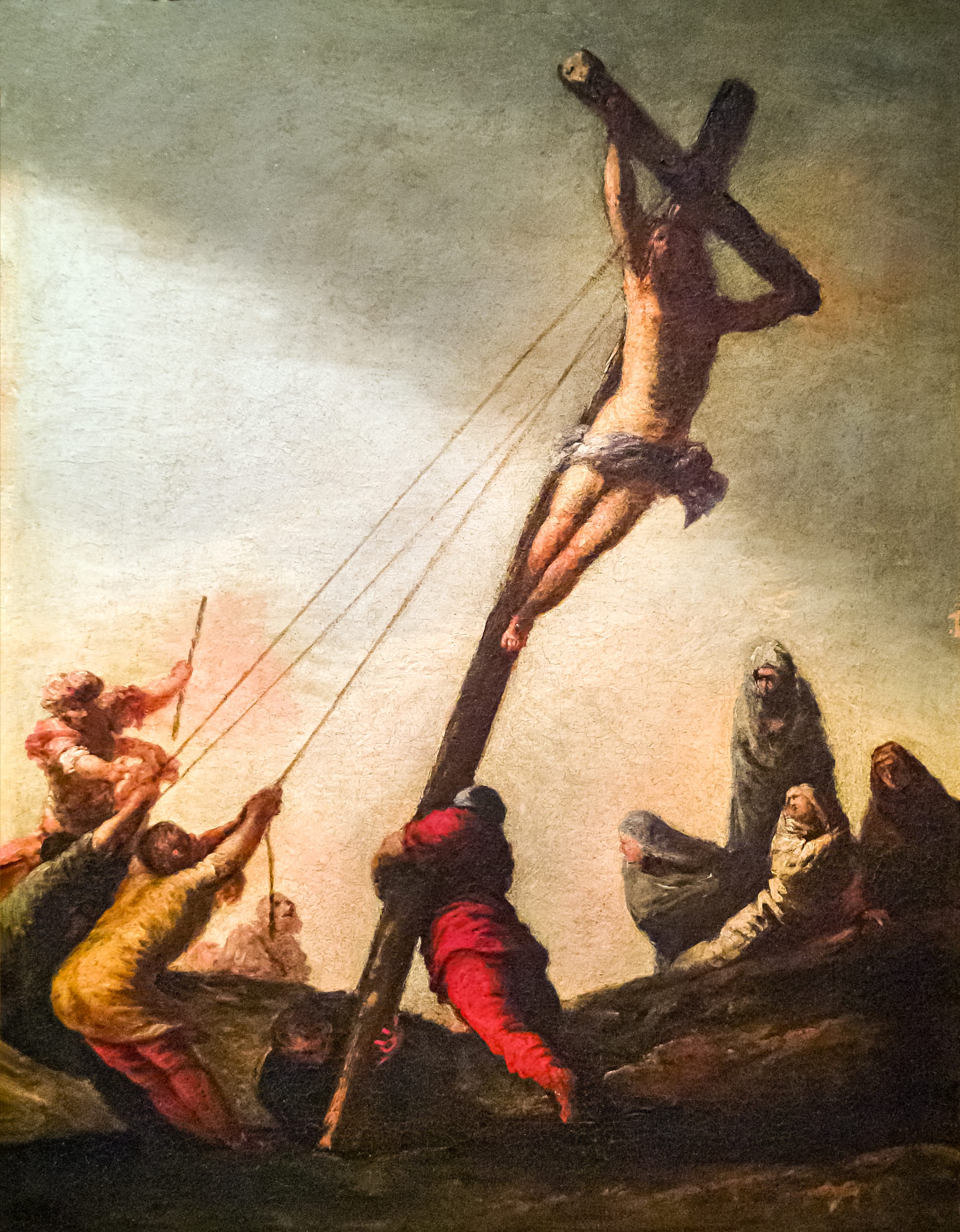

The crucifixion of Jesus is a central event in Christian history but why did the Romans kill him? What was the motive behind Jesus’ death? The crucifixion of Jesus involves multiple layers of political, social, and religious contexts. The Romans, who controlled Judea during the time of Jesus, played a crucial role in his execution.

What was the background before Jesus’s death?

Judea was under Roman occupation, and the Roman governor Pontius Pilate was responsible for maintaining law and order. The Romans were particularly sensitive to any form of rebellion or unrest that could threaten their control.

Christianity emerged in Judea during the mid-first century CE, initially centered on the teachings of Jesus and later expanded through the writings and missionary efforts of Paul of Tarsus.

At its inception, Christianity was a small and loosely organized sect that offered the promise of personal salvation after death. This salvation was attainable through faith in Jesus as the son of God, the same deity worshipped by Jews. Early Christians debated whether their message should be exclusive to Jews or if it should also include Gentiles. Over time, Christianity attracted adherents not only from Jewish communities but also from various parts of the Roman Empire.

Jesus was a peasant from a small town in a Roman province, distant from the hubs of political and religious authority. Individuals in such situations rarely posed any significant threat to Roman power. As a Jewish prophet and teacher known for performing miracles, Jesus did not present a typical threat to the Roman authorities. He neither took up arms nor encouraged his followers to do so.

Rome was highly vigilant regarding any potential uprisings. When actions of individuals or groups appeared even remotely seditious, Rome responded with swift and decisive violence. The Romans crucified hundreds, if not thousands of people—primarily slaves and suspected revolutionaries—and frequently employed military force in the provinces.

Given that Jesus was crucified, it is evident that he was executed by the Roman authorities (Jewish authorities did not practice crucifixion). Although Jesus did not wield conventional political power, his actions and teachings posed threats to the existing order.

One of the most significant threats Jesus posed was his ability to attract large crowds. The gospels describe how great crowds followed him. When he entered Jerusalem during the last week of his life, he was welcomed with local fanfare. His popularity, combined with the gathering of possibly hundreds of thousands of pilgrims in Jerusalem for Passover, would have made Roman authorities extremely uneasy.

Why did the Romans crucify Jesus?

The Romans crucified Jesus because the Sanhedrin condemned him to death for blasphemy, claiming he declared himself to be the Messiah, the Son of God. While the accounts in Mark and Matthew align on this narrative, Luke does not mention any condemnation by the Sanhedrin or accusations of blasphemy, and John does not reference any Sanhedrin meeting on the night of Jesus' arrest. These discrepancies in the biblical accounts suggest that the motivations and events leading to Jesus' crucifixion may not have been entirely consistent.

What is clear is that Jesus was executed on political charges. Many people believe that Jesus fell foul of the authorities because he committed blasphemy or offended the religious leaders of his day (such as the Pharisees and the Sadducees of the Sanhedrin). Jesus had been referred as the King of the Jews by his followers.

This title was interpreted politically, not spiritually as the biblical text insinuates. Being a king meant being the political leader of the people of Israel, a role that could only be appointed by the Roman governor or someone the Romans approved of, like Herod. Anyone else claiming to be king was seen as usurping Roman authority and was viewed as a threat or a public nuisance.

So, although the Romans were indifferent to Jewish blasphemy or internal Jewish disputes about doctrine and practice, they could not allow for the threat of insurgency, and had methods for dealing with lower-class peasants who were seen as troublemakers or public nuisances.

They crucified them.

There are numerous reasons to believe this was indeed the charge against Jesus. Contextually, it makes sense, as the Romans did not execute people without a cause or simply for offending Jewish religious sensibilities. More importantly, this charge is consistently mentioned in multiple sources, including the accounts in Mark and John, during both the trial and crucifixion scenes. Additionally, this charge is unlikely to have been fabricated by early Christians, as it meets the criterion of dissimilarity.

The term "King of the Jews" is significant. Jesus never uses it to refer to himself in the Gospels, nor is it a term used by any first-century Christian author to describe him. Its presence as the charge against him at his trial and on the placard at his crucifixion strongly suggests it was indeed the genuine charge brought against him.

What was Pontius Pilate’s role?

Pontius Pilate is a crucial figure in Christian history because of his involvement in the trial and crucifixion of Jesus Christ. In historical terms, Pilate was the Roman prefect (governor) of Judea from 26 to 36 CE, serving under Emperor Tiberius. During his tenure, Pilate made a significant decision that led to the execution of a Jewish rebel, Jesus of Nazareth, and his decision inadvertently contributed to the foundation of Christianity, which would grow into a major world religion.

Josephus Flavius, a Roman-Jewish historian, writing approximately fifty years after Pontius Pilate sentenced Jesus Christ to death, offers an insightful historical view of this elusive Roman official. According to Josephus, Pilate funded the construction of an aqueduct to bring water into Jerusalem using money from the Temple treasury, sparking public outrage.

Unlike previous instances, Pilate did not yield to the protesters' demands. Instead, he sent plain-clothed soldiers to blend in with the crowd. At his signal, these soldiers used clubs hidden in their garments to assault the protesters, resulting in the deaths of many demonstrators.

Josephus also documented Pilate's notorious role in the execution of Jesus. Unfortunately, the original account is lost, and the existing version is widely discredited by scholars. Despite its altered state, Josephus' account depicts a Roman governor tasked with maintaining peace in one of the Empire's most volatile provinces. Pontius Pilate appears to have managed this effectively, retaining his position for ten years, which is notably long given the frequent tensions and uprisings in the region.

Shortly after Jesus' trial, Pontius Pilate faded from historical records. According to Flavius Josephus and Tacitus, after brutally suppressing a suspected Samaritan uprising, he was summoned back to Rome by his superior, the legate of Syria, to justify his actions before Emperor Tiberius.

This is the last historical mention of Pilate, who inadvertently played a significant role in the development of Christianity. Pilate's recall in 36/37 CE coincided with Tiberius' death, so his trial would have fallen under the jurisdiction of the new emperor, Caligula. It is unclear if a hearing ever took place, as new emperors often dismissed pending legal cases from their predecessor’s reign or granted pardons. Pilate might have been among those acquitted after Caligula's ascension.

However, the fourth-century church historian Eusebius claims that, according to tradition, Pilate committed suicide after being recalled to Rome due to disgrace. There is no historical evidence supporting this claim. Some traditions, including those of the Coptic Church, suggest that Pilate converted to Christianity and is venerated as a saint.

How do the Gospels present the story?

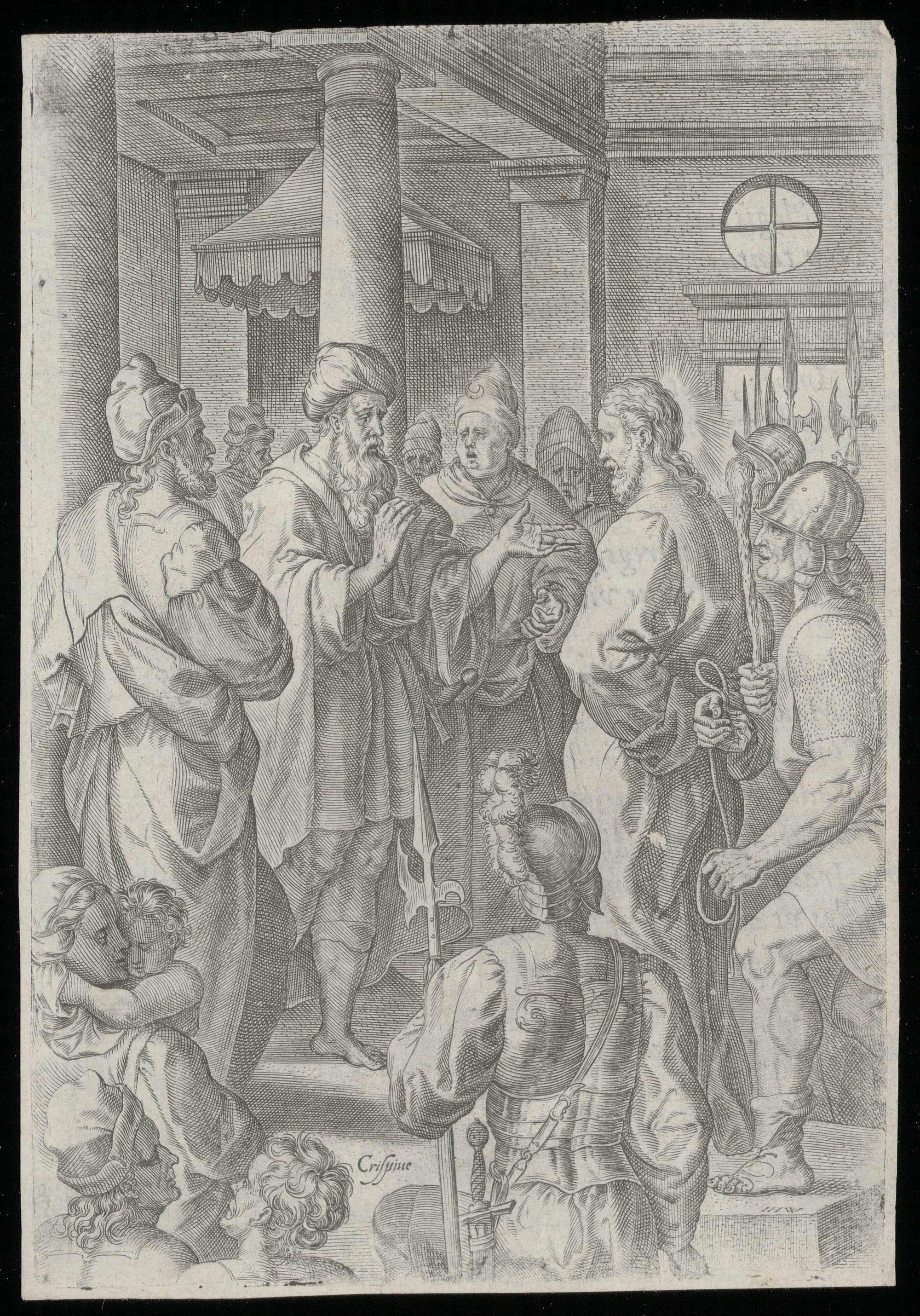

The account of Jesus' final days, a fundamental aspect of Christianity, is widely known. Accused of making false messianic claims and viewed as a threat due to his teachings, Jesus was arrested by the Jewish priestly council, the Sanhedrin, during the Passover festival.

They brought Jesus before Pontius Pilate to be tried for blasphemy—specifically for claiming to be the King of the Jews. This was a serious charge, as the only legitimate authority in Judea was the Roman emperor and his representative, the prefect and procurator. However, the Gospels depict Pontius Pilate not as a harsh official but as a hesitant judge. According to the Gospel of Mark, Pilate tried to defend Jesus but ultimately gave in to the crowd’s demands.

The Gospel of Matthew adds a dramatic scene where Pilate washes his hands before the crowd, declaring himself innocent of Jesus’ blood in an attempt to distance himself from responsibility for Jesus' fate. The crowd's response, "His blood be on us and our children," as recorded in the Gospel of Matthew, has had a profound and tragic impact on history, as this line has been misused to justify anti-Semitic attitudes and actions over the centuries.

What are the existing references to Jesus?

Within a century of the traditional date of Jesus's death, Roman authors mention him on three occasions. Notably, none of these references were made during Jesus's lifetime or even in the first century of Christianity. These authors were writing about eighty to eighty-five years after the traditional date of his death.

Pliny the Younger

The first surviving reference to Jesus from a non-Christian, non-Jewish source appears in the writings of Pliny the Younger, who was the governor of the Roman province of Bithynia-Pontus in Asia Minor (now Turkey). Pliny is distinguished from his famous uncle, Pliny the Elder, a renowned natural scientist who tragically died investigating the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. Pliny the Younger observed the eruption from a safe distance and documented it in his writings.

Among early Christianity scholars, Pliny the Younger is best known for a series of letters to the Roman emperor Trajan, in which he sought advice on governing his province. Letter number 10, written in 112 CE, is particularly significant as it contains what appears to be a mention of Jesus. However, the letter itself addresses a political issue rather than focusing on Jesus directly.

In Pliny's province, a law had been enacted that prohibited social gatherings to prevent potential political uprisings. This law inadvertently included fire brigades, leading to a lack of effective fire-fighting measures and resulting in villages burning down.

In his letter number 10 to the Emperor, Pliny discusses the fire problem and, in that context, mentions another group that was illegally gathering—the local community of Christians. Pliny learned from reliable sources that the Christians gathered early in the morning, including people from various socioeconomic levels, and ate meals of common food. He likely mentioned this to counter rumors of cannibalism, as Christians were said to eat the flesh of the Son of God and drink his blood. Pliny informs the Emperor that the Christians "sing hymns to Christ as to a god."

This brief mention of Jesus is significant as Pliny notes that the Christians worshipped him by singing to him. Pliny refers to him as Christ, not Jesus, which suggests he may not have known Jesus's actual name. This reference confirms that Christians were worshipping Christ in the early second century in Asia Minor, information already known from other Christian sources.

Suetonius

Another reference is found in the writings of the Roman biographer Suetonius, best known for his twelve biographies of Roman emperors. In his biography of Claudius, emperor of Rome from 41 to 54 CE, Suetonius mentions that Claudius deported all the Jews from Rome because of riots instigated by "Chrestus".

This name has led scholars to speculate that Suetonius was referring to Christ and the tensions caused by Jewish Christians in Rome. This theory finds some support in the New Testament book of Acts (18:2). However, since Chrestus was a common name, it's possible Suetonius referred to another individual entirely.

Tacitus

Lastly, the Roman historian Tacitus provides a more promising reference to Jesus. Tacitus mentions Christians and their persecution under Nero, providing valuable evidence for the existence and early spread of Christianity.

Tacitus wrote his famous Annals of Imperial Rome in 115 CE as a history of the empire from 14 to 68 CE. Probably the best-known single passage of this sixteen-volume work is the one in which he discusses the fire that consumed a good portion of Rome during the reign of the emperor Nero, in 64 CE.

According to Tacitus, it was the Emperor himself who had arranged for arsonists to set fire to the city because he wanted to implement his own architectural plans and could not very well do so while the older parts of the city were still standing. But the plan backfired, as many citizens—including those, no doubt, who had been burned out of house and home-suspected that the emperor himself was responsible.

Nero needed to shift the blame onto someone else, and so, according to Tacitus, he claimed that the Christians had done it. The populace at large was willing to believe the charge, Tacitus tells us, because the Christians were widely maligned for their "hatred of the human race".

And so Nero had the Christians rounded up and executed in very public, painful, and humiliating ways. Some of them, Tacitus indicates, were rolled in pitch and set aflame while still alive to light Nero's gardens; others were wrapped in fresh animal skins and had wild dogs set on them, tearing them to shreds.

In the context of this gory account, Tacitus explains that:

"Nero falsely accused those whom... the populace called Christians.

The author of this name, Christ, was put to death by the procurator, Pontius Pilate, while Tiberius was emperor; but the dangerous superstition, though suppressed for the moment, broke out again not only in Judea, the origin of this evil, but even in the city [of Rome]."

Once again, Jesus is not actually named here, but it is obvious in this instance that he is the one being referred to and that Tacitus knows some very basic information about him. He was called Christ, he was executed at the order of Pontius Pilate, and this was during the reign of Tiberius.

Moreover, this happened in Judea, presumably, since that was where Pilate was the governor and since that was where Jesus's followers originated. All of this confirms information otherwise available from Christian sources, as we will see.

At the same time, the information is not particularly helpful in establishing that there really lived a man named Jesus. How would Tacitus know what he knew? It is obvious that he had heard of Jesus, but he was writing some eighty-five years after Jesus would have died, and by that time Christians were certainly telling stories of Jesus (the Gospels had been written already, for example), whether the mythicists are wrong or right.

It should be clear in any event that Tacitus is basing his comment about Jesus on hearsay rather than, say, detailed historical research. Had he done serious research, one might have expected him to say more, if even just a bit. But even more to the point, brief though his comment is, Tacitus is precisely wrong in one thing he says; he calls Pilate the "procurator" of Judea.

We now know from the inscription discovered in 1961 at Caesarea that as governor, Pilate had the title and rank, not of procurator (one who dealt principally with revenue collection), but of prefect (one who also had military forces at his command). This must show that Tacitus did not look up any official record of what happened to Jesus, written at the time of his execution (if in fact such a record ever existed, which is highly doubtful). He therefore had heard the information, but whether he heard it from Christians or someone else, we cannot know.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: