What was the Severan Marble Plan?

In the ruins of an ancient city, amidst temples and columns long abandoned, lied the shattered remains of something truly extraordinary.

Etched with intricate lines and symbols, the fragments of Forma Urbis Romae, whisper secrets of a time when the empire was at its height, its power immortalized in stone.

Scattered across museums and archives, the pieces begged the question: what grand purpose did they serve? Was it a map, a puzzle, or a message meant to endure the ages? And why, after centuries, do these fragments still captivate the imagination of those who seek to uncover their meaning? The answers lie hidden in the ruins, waiting to be revealed.

Rediscovering the Great Marble Map of Rome: A Modern Approach

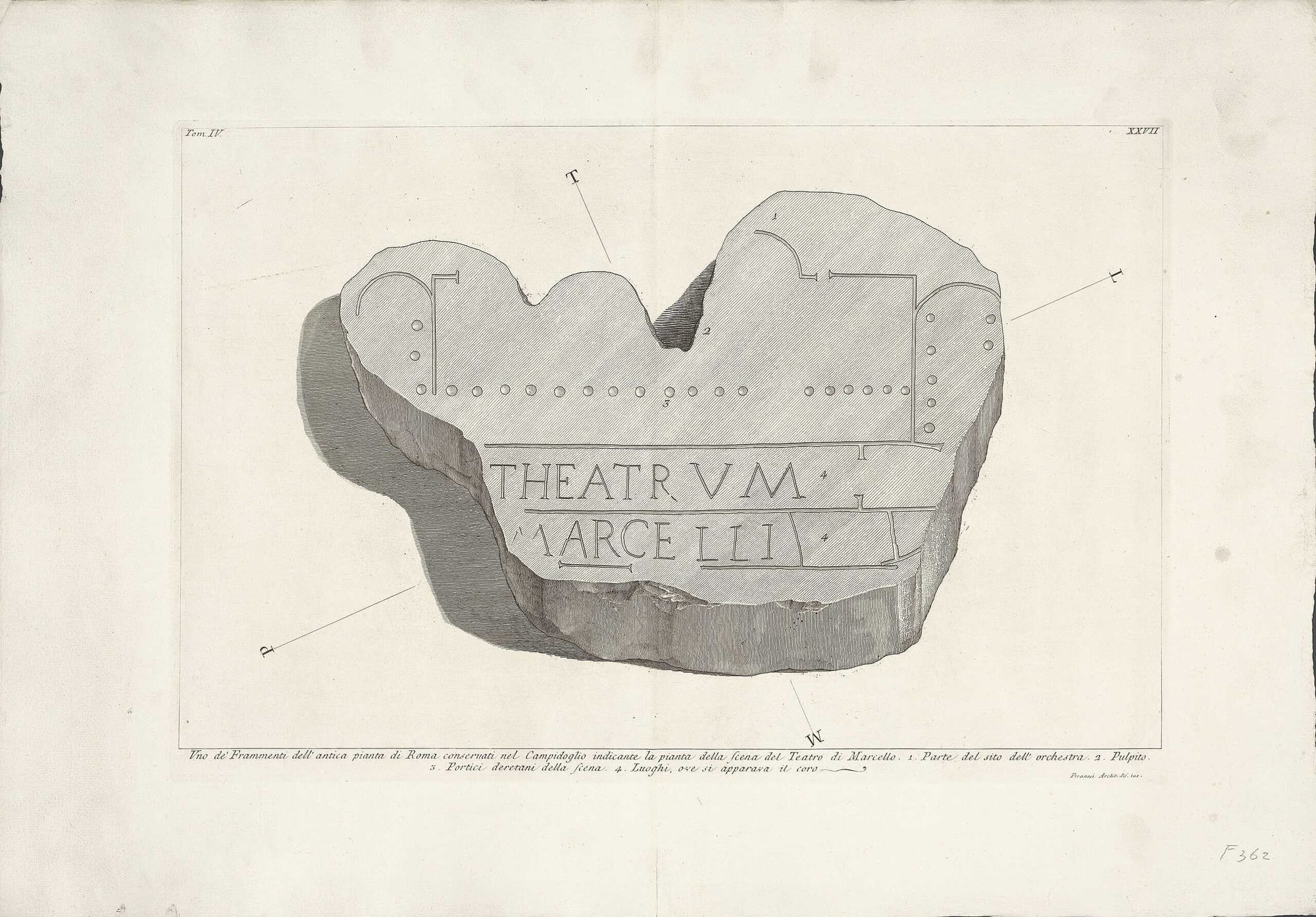

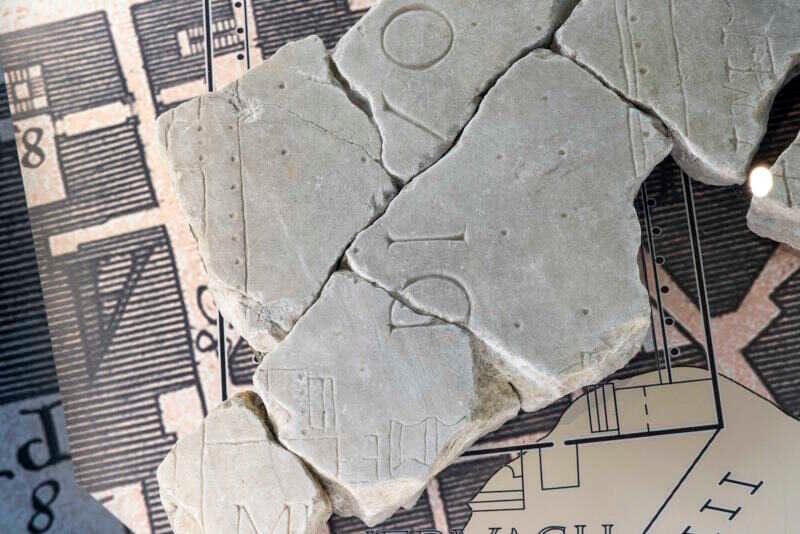

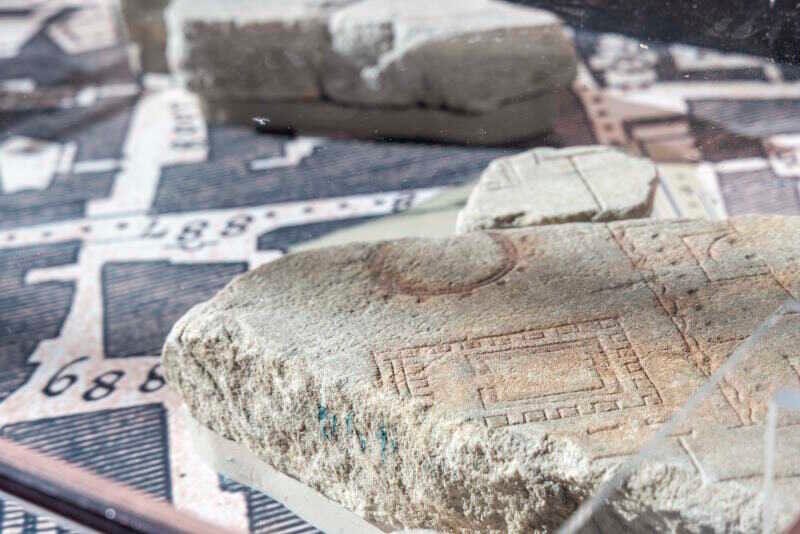

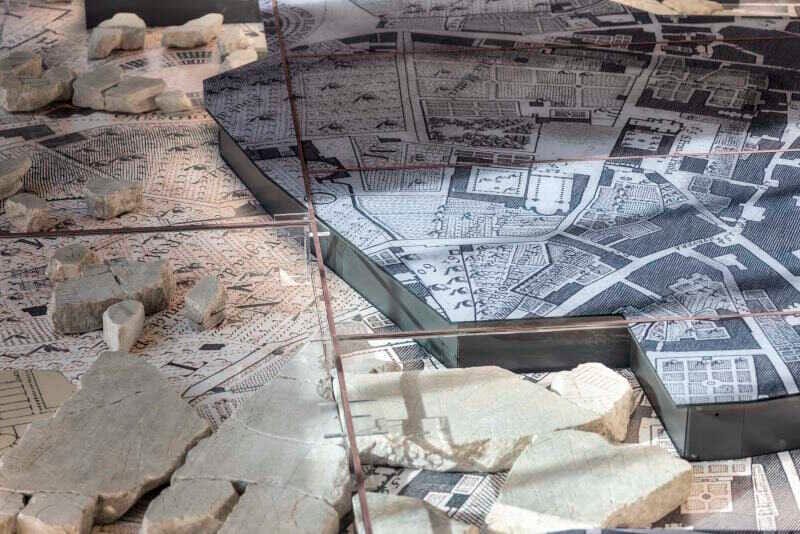

The Forma Urbis Romae, also known as the Great Marble Map of Rome, was a massive 13 x 18 meter (±42.5 x 59 feet) depiction of the city created during the Severan Dynasty (193–235 CE). This detailed map showed the layout of neighborhoods and buildings across Rome and was originally displayed on the interior wall of the Temple of Peace near the Roman Forum.

Today, only about 10% of the original map survives, scattered across roughly 1,200 fragments.

Marble fragment with map of Theatre of Marcellus in Rome, from the Severan Marble Map. Credits: Rijksmuseum, Public domain

Over time, the map was gradually destroyed during the Middle Ages, with its marble fragments repurposed for other construction projects. The wall that once held the map now forms part of the Basilica dei Santi Cosma e Damiano. Although the map itself is long gone, the mounting holes for the metal clamps that once secured the marble slabs remain visible. These holes are crucial for efforts to reconstruct the map.

In 2018, a collaborative project involving institutions such as the Ancient World Mapping Center (UNC Chapel Hill, USA), Musei Capitolini in Rome, IUPUI, and Queen’s University, Canada, began to digitally document the wall and its fragments.

Traditional methods for documenting the mounting wall faced several challenges. The wall’s height and the distance from the street made setting up equipment like LiDAR scanners difficult. Moreover, the holes vary in size—from as small as 3 cm (±1.2 inches) to as large as 20 cm (±7.9 inches)—and are often difficult to distinguish from centuries of wear and decay on the wall’s surface.

To address these issues, the team used an advanced photogrammetry technique known as gigapixel panoramic photogrammetry. This method, originally used in mining, involved capturing high-resolution panoramic images from 50 meters (164 feet) away using a telephoto lens. The approach eliminated the need for scaffolding or drones, making it a cost-effective and efficient solution.

This innovative technique created precise, three-dimensional models of the wall with a relative accuracy of less than 5 mm. The resulting panoramic images allowed researchers to inspect the wall in incredible detail, documenting its condition and mapping the mounting holes without the need for direct physical access. This modern approach marks a significant step forward in reconstructing the Great Marble Map of Rome and understanding the city’s ancient architectural history.

Fragmentary Clues to Ancient Rome

The discovery of the first fragments of the map, occurred in 1562 behind the Church of St. Cosmas and Damian. This initial finding provided the first evidence of this monumental map’s existence; over the following centuries, additional fragments were unearthed across Rome, either during deliberate archaeological excavations or by pure chance.

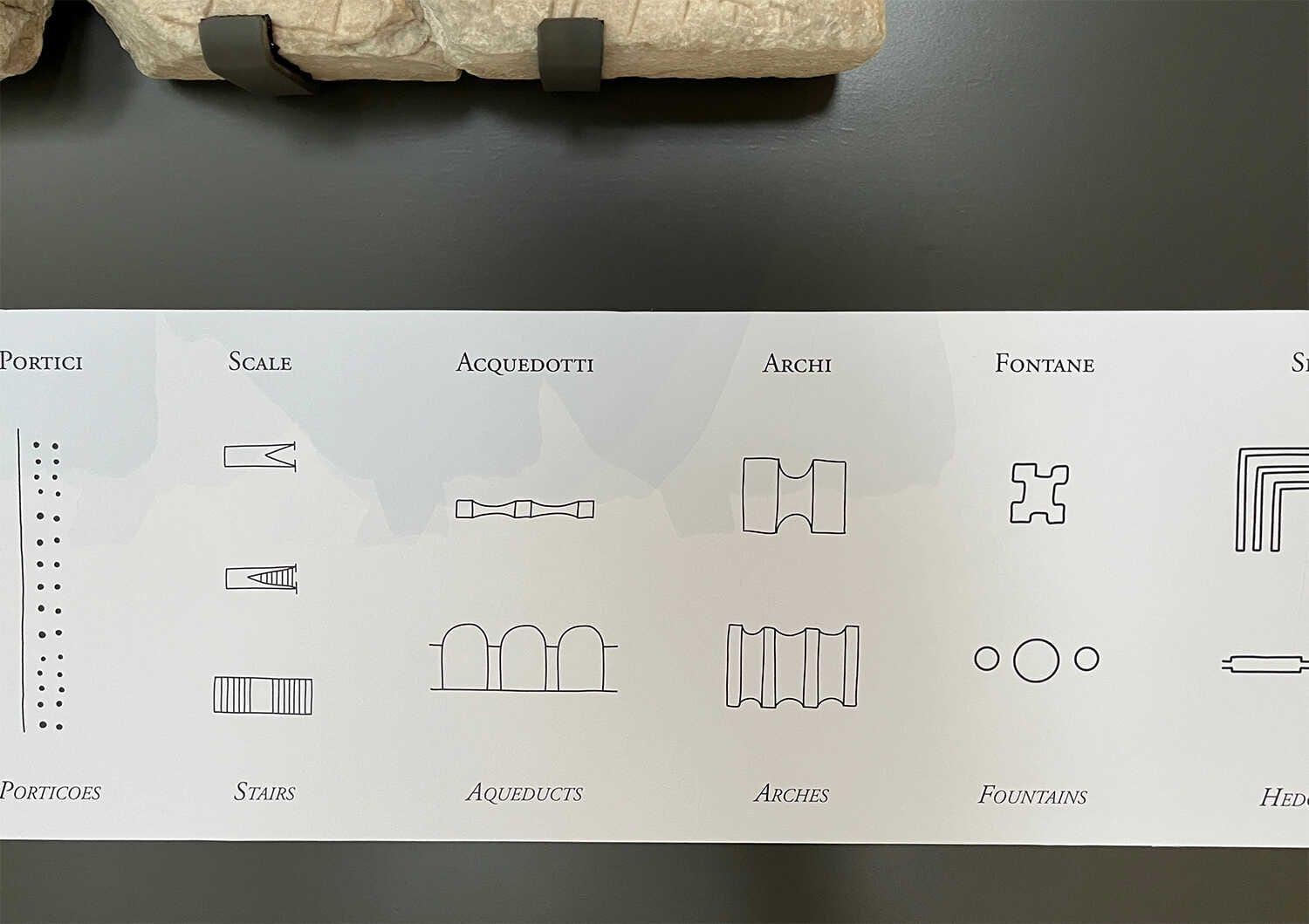

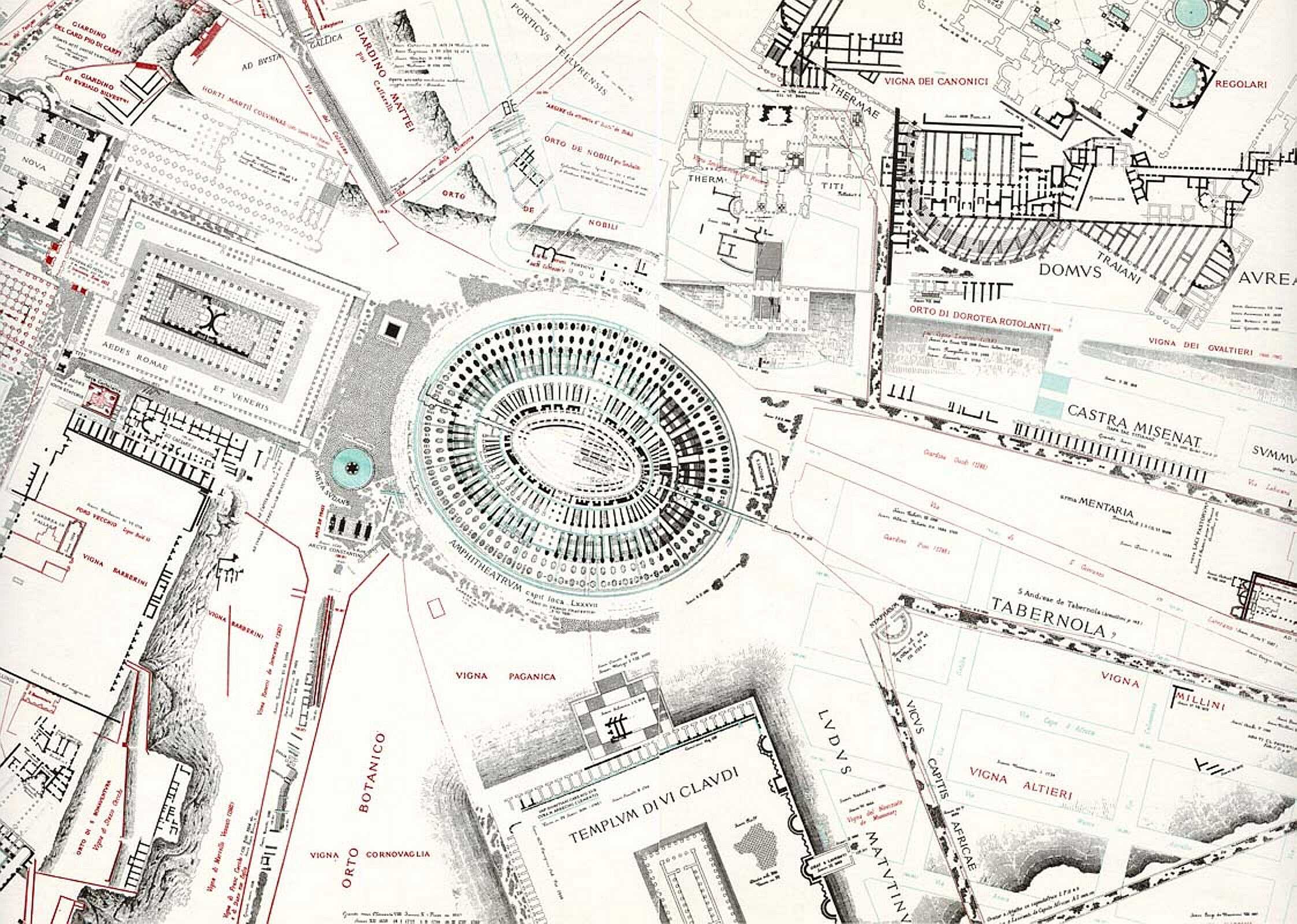

Some fragments were identified by the engraved depictions of recognizable locations, such as the Colosseum, the imperial fora, (a series of monumental public squares (fore), constructed in Rome over a period of one and a half centuries, between 46 BC and 113 AD) and the Capitoline Hill. However, of the fragments found to date, only around 200 have been conclusively identified, approximately 500 remain unidentified, and the rest lack visible incisions.

The map, holds unique value as one of the few surviving records of ancient Rome’s urban planning. It offers insights not only into monumental structures but also into residential areas and daily life in the city. Created at a highly detailed scale of 1:240, the map depicted everything from grand architectural designs to sidewalks, doorways, and interior staircases.

While some fragments include labels and notations for prominent landmarks, others feature only the designs of structures.

A legend of the symbols found on the Severan marble map. Credits: Brent Nongbri

So far, the fragments have revealed 55 identifiable structures, six streets, and seven larger areas. Modern scholarship on the map has its foundation in the seminal two-volume publication from 1960 by Carettoni et al., which remains the primary reference for its history.

This publication offered the first comprehensive catalog of the known fragments, their original setting in the Temple of Peace (also known as the Forum of Vespasian, was built in Rome in 71 AD under Emperor Vespasian, in honour to Pax, the Roman goddess of peace) and their historical and functional context. While no direct mentions of the map exist in ancient texts, scholars have dated its creation to the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus, specifically after the fire in the Temple of Peace in 192 CE.

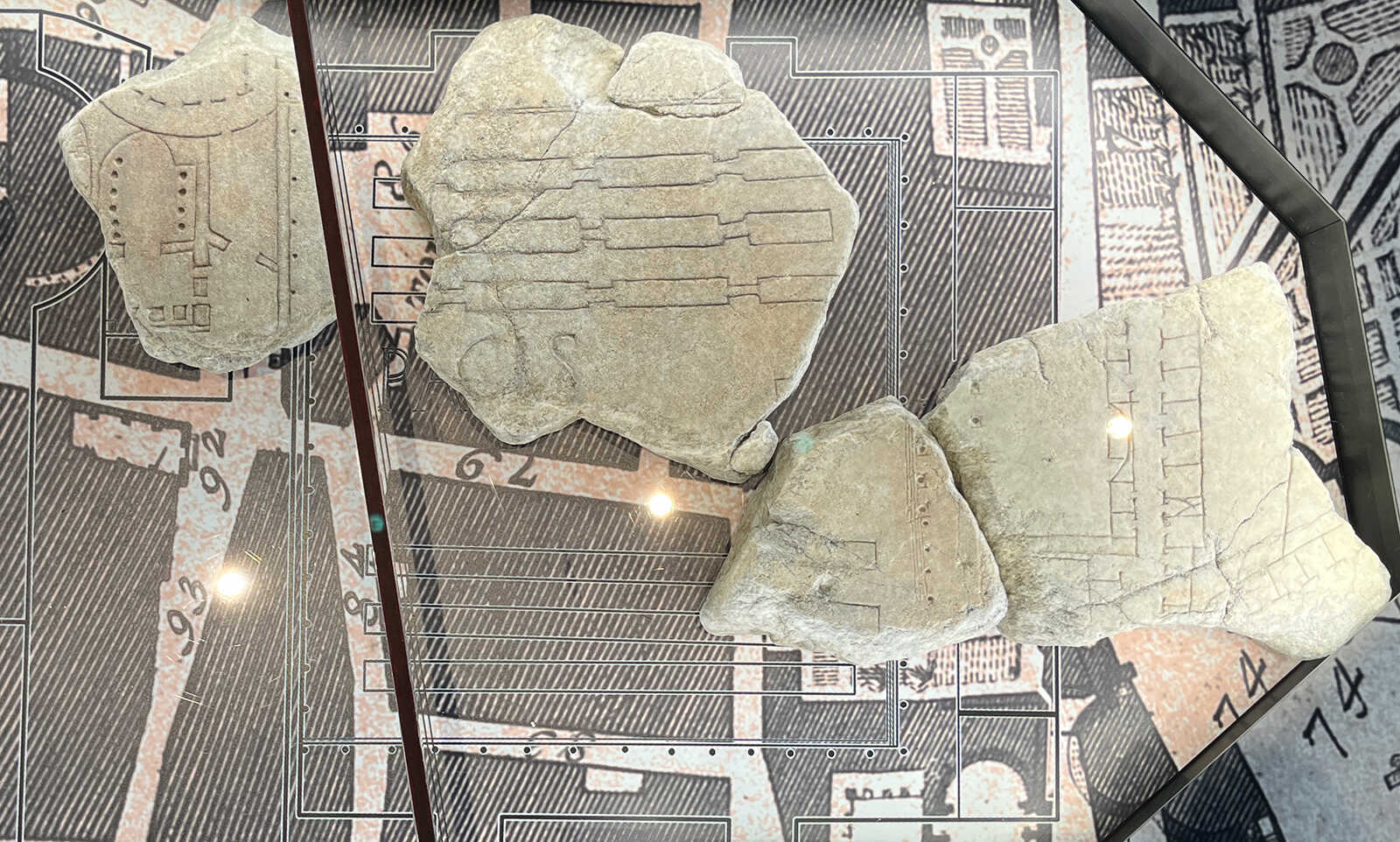

In 1999, Stanford University began an ambitious project to laser-scan the fragments, creating a digital database aimed at virtually reconstructing sections of the map and identifying new matching fragments. However, the project lacked a corresponding 3D model of the wall that originally held the map, which could assist in aligning clamp holes on the backs of the fragments with those still visible on the wall.

Building on these efforts, the Great Marble Map of Rome Project was launched in 2018. This initiative sought to digitize the fragments, document the mounting wall, and advance the study of the Forma Urbis Romae. New 3D scans of the fragments were conducted using handheld structured light scanners, improving upon the earlier database created by Stanford.

Researchers also began exploring the use of machine learning to identify and match fragments, marking a significant step forward in the digital reconstruction and study of this monumental artifact. (Gigapixel Photography For High-Accuracy Facade Documentation: Mapping The original location Of The Forma urbis Romae, by K. Jones1, G. Bevan, R. Talbert, E. Wolfram Thill, D. Lehoux)

Unlocking Ancient Mysteries Through Modern Technology

In January 2019, Elizabeth Wolfram Thill presented a groundbreaking paper at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Classical Studies in San Diego, focusing on new advancements in the study of the Forma Urbis Romae.

This colossal artifact, originally spanned over 2,500 square feet and depicted the architectural layout of every ground floor room in the city. However - as already mentioned- only 10-15% of the map survives today, scattered across approximately 1,200 fragments, some weighing dozens of pounds. The challenges of piecing together this massive “puzzle” have persisted for centuries, but Thill’s presentation highlighted the transformative role of modern technology in overcoming these obstacles.

A Monument of Complexity

The map presented immense logistical and scholarly difficulties. Its fragments often featured generic and unidentifiable buildings, making interpretation challenging. The map’s original dimensions further complicated efforts to contextualize its features, as many details would have been difficult to see on such a large scale.

Traditionally, scholars focused on individual fragments or identifiable structures, such as the Colosseum, but this piecemeal approach limited understanding of the map as a whole.

Advancing Access Through Technology

Thill introduced the Great Marble Map of Rome Project, spearheaded by the Ancient World Mapping Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, in collaboration with the Musei Capitolini and the Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali in Rome. The project aimed to make the map more accessible, promote new research directions, and engage the public.

Central to this initiative was the creation of a comprehensive online database featuring three-dimensional scans of all 1,200 fragments. These scans would allow researchers and the public to explore the fragments virtually and in their original context.

Scanning the Wall of the Marble Map

A significant milestone of the project was the photogrammetric scanning of the wall where the Great Marble Map once hung. Using advanced photogrammetry techniques, the team captured precise three-dimensional images of the wall, allowing detailed study of its features from a distance of 50 meters (164 feet).

The resulting scans, accurate to within 1 mm, revealed even the textures of individual bricks.

Remains of the Severan marble map, on the left the Temple of Minerva, on the right the Temple of Peace. Credits: Brent Nongbri

New Tools for Study

The project emphasized creating tools for better understanding the fragments. Using software like AutoCAD and Sketchfab, researchers produced annotated models of fragments with color-coded features such as inscriptions, columns, and commercial buildings.

These models facilitated easier identification of fragment joins and opened avenues for exploring broader questions, such as how structures were represented or how space was conceptualized in ancient Rome.

A key component of the initiative was making the map more accessible to the public. Plans included a new museum in Rome, located near the Colosseum, to house and display the fragments. Visitors would be able to view the pieces in person, while scholars could test hypotheses developed online against the actual artifacts.

Additional goals included developing educational curricula, creating a mobile app for tourists, and even exploring virtual reality experiences that would allow users to walk through reconstructed buildings depicted on the map.

The team envisioned ambitious long-term projects, such as rescanning all fragments with modern laser technology to improve detail and creating a continuously updated database incorporating new discoveries. They also hoped to crowdsource fragment joins, inviting contributions from an engaged public.

#1: Focusing on the Colosseum

#2: Focusing on the Tiber Island

#3: Focusing on the Campus Martius

Courtesy of Turismo Roma

Investigating the Hidden Geometry of Ancient Rome: The “Altera Forma Urbis”

In their groundbreaking study, “Altera Forma Urbis: Interpreting the Hidden Geometry of Ancient Rome,” Giuseppe Lugli, Pier Maria Lugli, and Gianfranco Moneta proposed a fascinating theory that unravels the geometric framework underlying the urban layout of ancient Rome.

This work, enriched by the contributions of architects Maurizio Crocco and Andrea Moneta as part of the C40 “Reinventing Cities” initiative, bridges ancient Roman urbanism with modern principles of sustainable design, offering innovative insights into both historical and contemporary city planning.

This research explores the intriguing concept of the “Altera Forma Urbis,” a theorized geometric framework underlying ancient Rome’s layout. Proposed by Italian archaeologists Giuseppe and Pier Maria Lugli and later expanded by Gianfranco Moneta, this “hidden” structure is envisioned as a star-like design that connects key monuments and roads of ancient Rome. Through this lens, the study bridges Rome’s historical topography with contemporary urban planning, demonstrating how this ancient model might inform modern sustainable design practices.

Origins of the “Altera Forma Urbis”

The concept of the “Altera Forma Urbis” is rooted in the analysis of Rome’s ancient boundaries as described by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History. Pliny noted a perimeter of 13,200 Roman paces for the city, a measurement that exceeded the expected limits of the Servian or Aurelian walls. This anomaly led researchers to theorize a symbolic and geometric star shape as the city's true organizational principle.

The star, based on astronomical and geographic alignments, connects major ancient landmarks such as temples, forums, and roads. Its geometry suggests a deliberate design aligned with Rome's sacred and practical functions, possibly initiated during Nero's reign after the Great Fire of 64 CE. The model evolved through the Republican and Imperial eras, culminating in an eight-point star centered on the Forum of Peace, where the renowned marble map once hung.

#1: Focusing on the Templi di Largo Argentina

#2: The Museum of the Forma Urbis Romae

#3: Detail of the Forma Urbis Romae

Courtesy of Turismo Roma

Modern Implications of the Star Model

Extending the star’s geometry to Rome’s contemporary structure reveals correlations with the city’s modern grid and road systems, including connections to its seven-mile-radius boundary and the Grande Raccordo Anulare (GRA) ring road. Moneta’s work applied this star-shaped framework to analyze Rome’s development, linking the ancient city’s spatial logic to potential guidelines for modern sustainable urban design.

As of January 2024, the fragments of the Great Marble Map of Rome, are on display in their own museum, nestled within a newly established archaeological park.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: